The 2013 Knesset Election Results: A Preliminary Analysis of the Upcoming Parliament

What can we learn from the results of the 2013 elections at this early stage? IDI researcher Dr. Ofer Kenig draws conclusions from the trends that emerged on Election Day and sketches the anticipated nature of the 19th Knesset.

Introduction

The ballots have been counted and the results are now clear. The sleepy election campaign that was expected to have a predictable outcome has yielded dramatic and surprising results. With the final outcome now known after the counting of the double envelopes with the absentee ballots of soldiers and diplomats, the main features of the next Knesset can be discerned. Following is a preliminary analysis of the election results and some expectations for the 19th Knesset.

Voter Participation Stabilizes at Approximately 65%

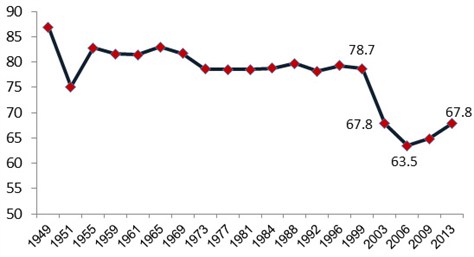

Before analyzing the distribution of votes, an interesting fact of the 2013 elections is the stability of the voter turnout rate. The voter turnout for the 2013 elections—67.8%—is slightly higher than that of the last two elections, but it is still far below the levels recorded in most of Israel's previous elections. For many years, Israel boasted high voter turnout rates. Until 1999, voter turnout averaged at around 80%. The sharp downturn came in 2001, when the special election for prime minister was held and only 62.3% of Israel's eligible voters actually went to the polls to vote. This may be explained by the unusual nature of that particular election, which was only for prime minister and not for the Knesset; this led to a lack of interest in the Arab sector, in which only 19 % of voters went to the polls. Those who expected voter turnout rates to return to their usual level in the next Knesset election, however, were sorely disappointed. In the four elections that have been conducted since the special elections for the prime minister, voter turnout has remained below 70%. The differences in voting rates in the last three elections have been negligible and the voting rate has consistently been around 65% of all eligible voters.

Figure 1: Voter Turnout Rates in Israel’s Electoral History

Status Quo in the Parliamentary Fragmentation

When it comes to parliamentary fragmentation, the new political map is not dramatically different from what came before it. Twelve lists will be represented in the 19th Knesset. This is in the middle of the historical range of parliamentary distribution in Israel, which has ranged from 10 at its lowest to 15 at its highest. In addition, it seems that the 2% electoral threshold, which has been in place since the 2006 election, is proving to be an effective barrier to new forces trying to enter the parliamentary arena. With the exception of Kadima, which made it over the threshold by a hair’s breadth, other parties such as Otzma LeYisrael, Am Shalem, Green Leaf (Aleh Yarok), Rabbi Amnon Yitzhak’s Koach Lehashpia, and Eretz Hadasha did not, and remained outside the Knesset. Nearly a quarter of a million voters were left without representation in the upcoming Knesset because they voted for parties that did not pass the electoral threshold. At close to 7%, this is a very high percentage of “wasted votes.”

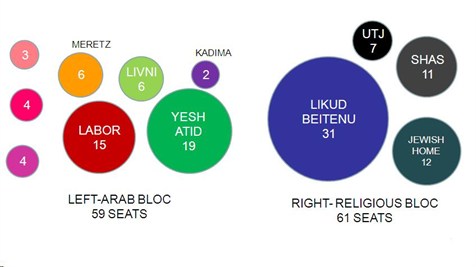

Figure 2: The New Party Map

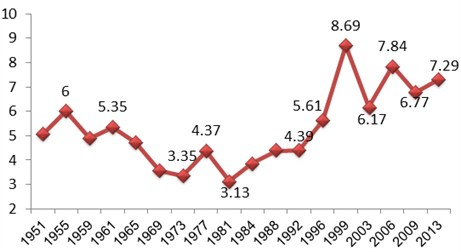

The failure of the small parties to pass the electoral threshold, however, does not hide the fact that fragmentation continues to be very high. The Effective Number of Parliamentary Parties (ENPP) is an accepted index for evaluating the degree of fragmentation in a parliament. This index reflects both the number of parties and their relative strength in concrete values, in the form of an adjusted number of political parties. The Effective Number of Parties in Israel (Figure 3) reflects the changes that have taken place in the degree of parliamentary fragmentation over the years. In the first decade of the state, the distribution of parties was relatively high. In the mid-1960’s, a process of amalgamation began, with parties consolidating into two blocs: Gahal (later the Likud) and the Alignment. This process reached its peak in the early 1980s. Following the elections of 1981, fragmentation was at its lowest. At that time, the Likud and Labor held a combined total of 95 of the Knesset’s 120 seats. Within 15 years, however, the picture changed radically: the introduction of direct elections for the prime minister, which was in effect between 1996 and 2003, brought an unprecedented amount of fragmentation. This method, in which voters had two ballots at their disposal—one for prime minister and the other for a Knesset party—allowed voters to split their vote; they could cast one ballot for a large party’s candidate for prime minister, and a second ballot for a small, sectoral party. This possibility led to a significant decrease in the power of the Likud and the Labor Party.

The degree of parliamentary fragmentation reached its peak in the elections of 1999, when the Effective Number of Parties jumped to 8.69. While the method of direct elections of the prime minster was abolished some ten years ago, its devastating consequences are still felt in Israel’s political system and the degree of parliamentary fragmentation still remains high. The ENPP value following the 2013 elections is slightly higher than the 2009 elections. It is the third highest in the history of Israel.

Figure 3. The Effective Number of Parliamentary Parties (ENPP)

And Now... It’s Time to Build a Coalition

Despite the relatively surprising election results, which indicate that the right-religious bloc have the thinnest Knesset majority (a total of 61 seats were won by Likud-Beiteinu, Shas, Habayit Hayehudi, and United Torah Judaism), it appears that the likelihood that Prime Minister Netanyahu will form the next government is still very high. It is already clear, however, that the task that faces him will not be easy. The primary reason for this is that even after the current elections, the ruling party has not regained its power. Until the elections of 1992 (inclusive), the ruling party always held a minimum of at least 40 Knesset seats. In the six Knesset elections that have been held since then, the ruling party has never won more than 40 seats. In three of those six elections, the ruling party won less than a quarter of the Knesset’s 120 seats.

When the Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu announced that they were forming a joint list in advance of the 2013 elections, it was expected that this move would yield a Knesset in which the ruling party is stronger than in the past. The election results, however, have dashed those expectations. While the two parties had a total of 42 seats in the outgoing Knesset, the joint list won a total of only 31 seats. This weakness will have a significant impact on the process of forming the government. Once again, the prime minister will have to build a coalition of at least four partners; once again, the ruling party will be a minority within the coalition.

.

The 19th Knesset: Many New MKs, More Women, and More Religious MKs

The anticipated make-up of the incoming Knesset will be marked by some significant changes. Firstly, no less than 48 new MKs will be sworn in—and that is without counting people who have been members of Knesset in the past but were not MKs at the time of the current elections (e.g., Tzipi Livni, Aryeh Deri, Amram Mitzna, and Nissan Slomiansky). If we include these MKs in the calculation, there will be 54 new members in the Knesset—nearly half the members of the house. All 19 of the MKs elected on Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid party list have never served in the Knesset before, the Labor Party has eight new Knesset members, and Habayit Hayehudi has eight new MKs.

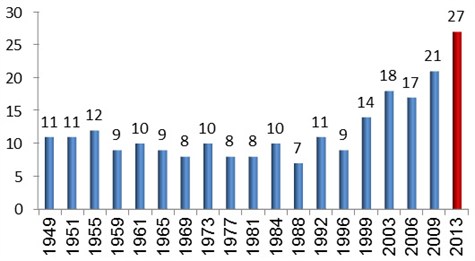

The 19th Knesset will also include a record number of women. Throughout Israel’s history, the number of women who were elected to the Knesset in each election ranged from a low of 7 (1988) to a high of 21 (2009). In the last three elections, there has been an increase in the representation of women in the Knesset. This increase continued in the current Knesset, in which a record high of 27 women will serve as MKs. Yesh Atid will have eight women in Knesset, Likud-Beiteinu will have seven, and the Labor Party will have four. Meretz will have three women representatives and Habayit Hayehudi will have three; Tzipi Livni’s Hatnuah and Balad will have one each.

Figure 4. The Number of Women in the Knesset after Each Election

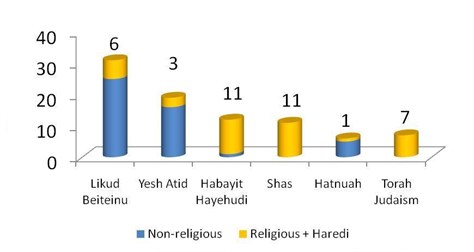

The new Knesset will also have an unprecedented number of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Knesset members: one in three members of the 19th Knesset will be religious. Religious MKs will not only be found in the sectorial religious parties (Shas with 11, Habayit Hayehudi with 11, and United Torah Judaism with seven), but also in the "general" parties. Six religious MKs will serve in the 19th Knesset as representatives of Likud-Beiteinu, there will be three in Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid, and there will be one in Tzipi Livni’s Hatnuah. It is interesting to note that two religious parties, Shas and Habayit Hayehudi, have a considerable constituency that is not religious, while a large number of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox voters vote for “general” parties.

Figure 5. Distribution of the 39 Religious and Ultra-Orthodox Knesset Members of the 19th Knesset by Party

Dr. Ofer Kenig is an IDI researcher who heads the Political Parties Research Team of IDI's Forum for Political Reform in Israel.