Happy Birthday, Knesset!

As the Knesset, Israel’s legislature, marks its birthday, IDI takes the opportunity to consider two aspects about it: its members’ social composition and its relative size.

The Knesset’s Members: A Mirror of Israeli Society?

At times, the Knesset, Israel's parliament, is referred to as “the legislature,” a term that testifies to one of its principal roles. It is also referred to as “the house of representatives,” since according to a widely-held perspective, it is supposed to reflect society, with all its varieties and groups.

Despite this, many studies have shown that the parliament’s composition is not an accurate reflection of society. For example, even though women comprise approximately half of the population, they make up a smaller percentage of the members of the parliament. This is also true of other social groups, such as national and religious minorities, young people, and members of groups with lower socioeconomic status.

In recent years, many parliaments have begun closing gaps, diversifying their composition. The representation of women has been increasing at a constant rate over the past 20 years, as has the presence of social minority groups.

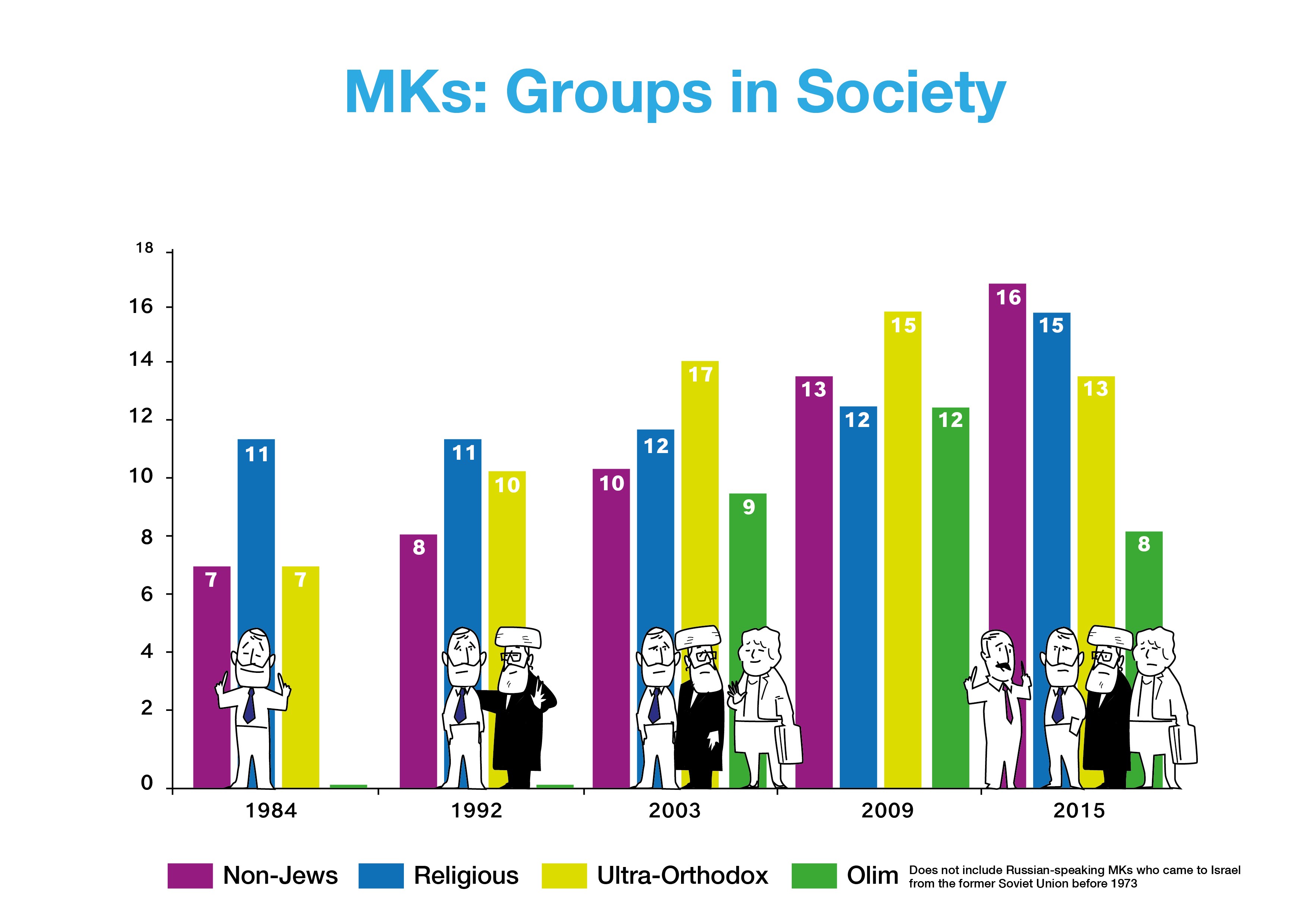

The Knesset has also become more varied over time. Part of the reason for this is demographics. In recent years, the composition of Israeli society has changed, including increases in the non-Jewish and ultra-Orthodox sectors. Another explanation has to do with changes in society’s values, for example, the significant increase in the number of women Knesset members is partially due to an improvement in the status of women in society.

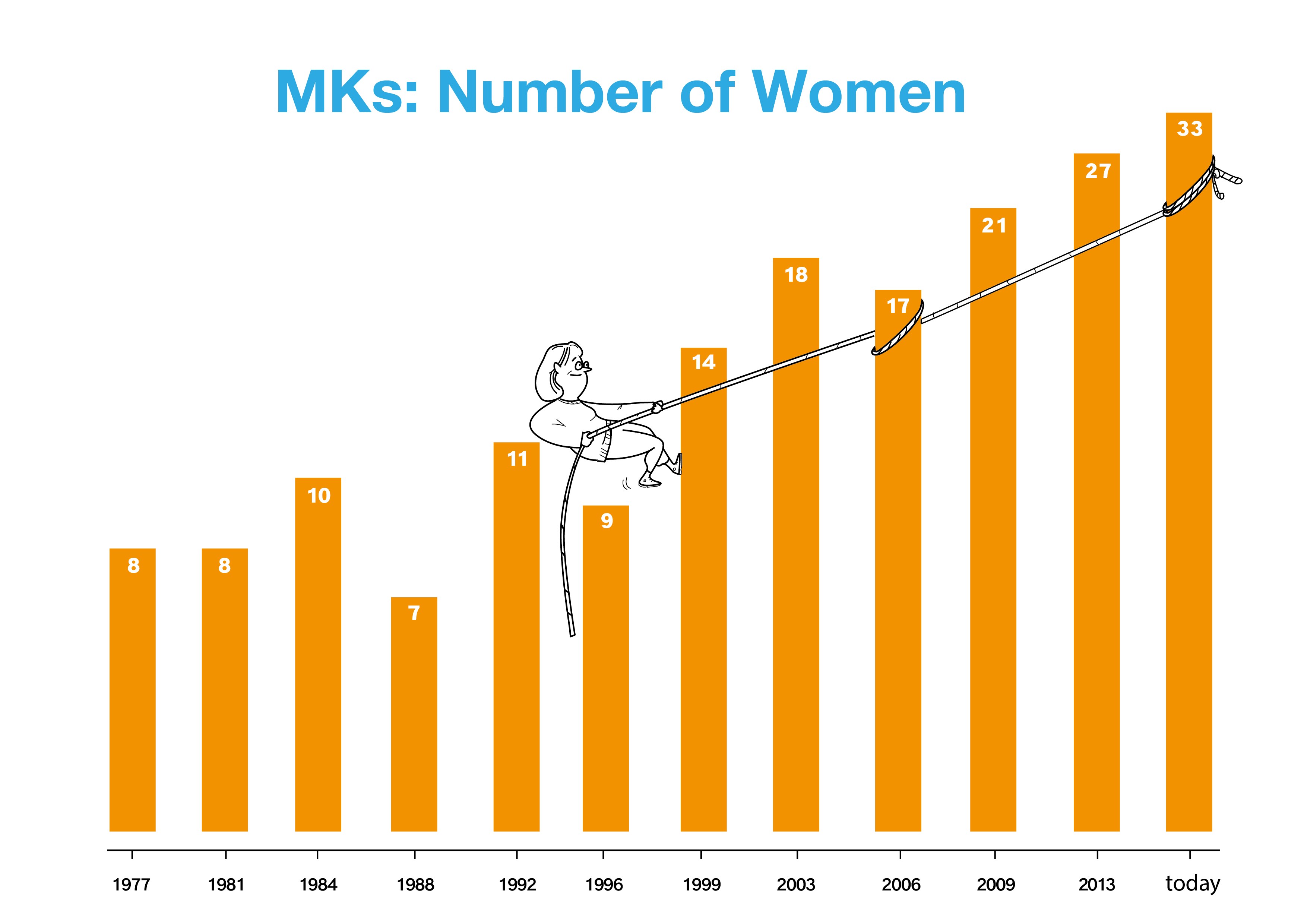

The number of women in the Knesset has soared from a nadir of seven after the 1988 elections to a current record high of 33. Of course, this number still does not reflect the proportion of women in the population, but is doubtless a significant improvement compared to the past.

See related article, "Women's Representation in the Knesset: Still Increasing But Not Fast Enough."

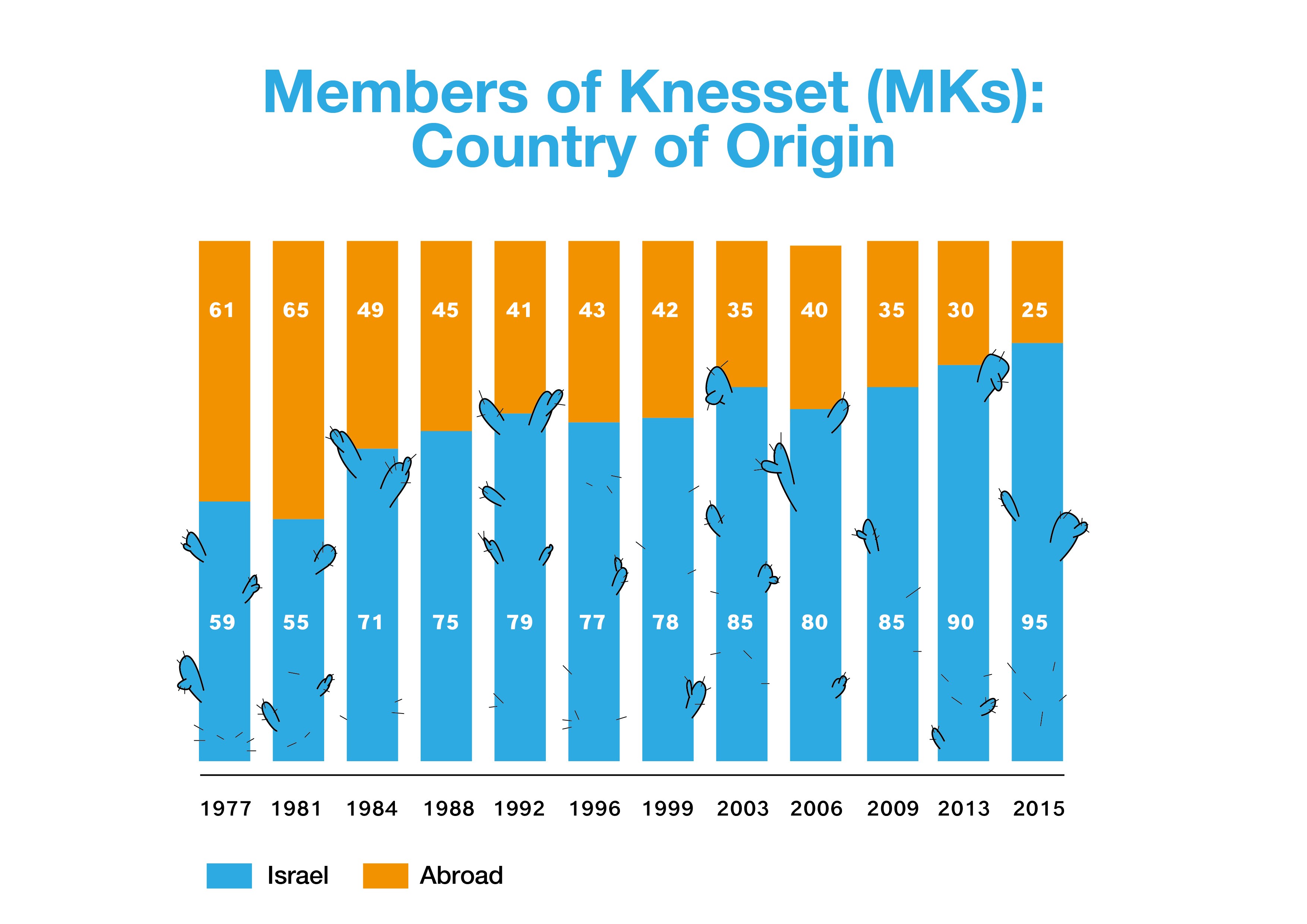

The changes in the composition of society also find expression in the number of sabra, or native-born, Knesset members. Since Israel is an immigrant state at the time of its founding, the first Knessets contained a large majority of members who were born abroad. The First Knesset contained only 15 members who had been born in Israel. Native-born Knesset members were a minority until the Tenth Knesset (1981). The first time that sabra Knesset members were a majority among Knesset members was in the Eleventh Knesset, which was elected in 1984.

The large wave of immigration from the Former Soviet Union during the 1990s slightly slowed the increase in the number of native-born Knesset members, as quite a few new immigrants were elected, but the number of sabras has grown steadily over the past decade. Currently, 95 of the 120 members of Knesset are native-born.

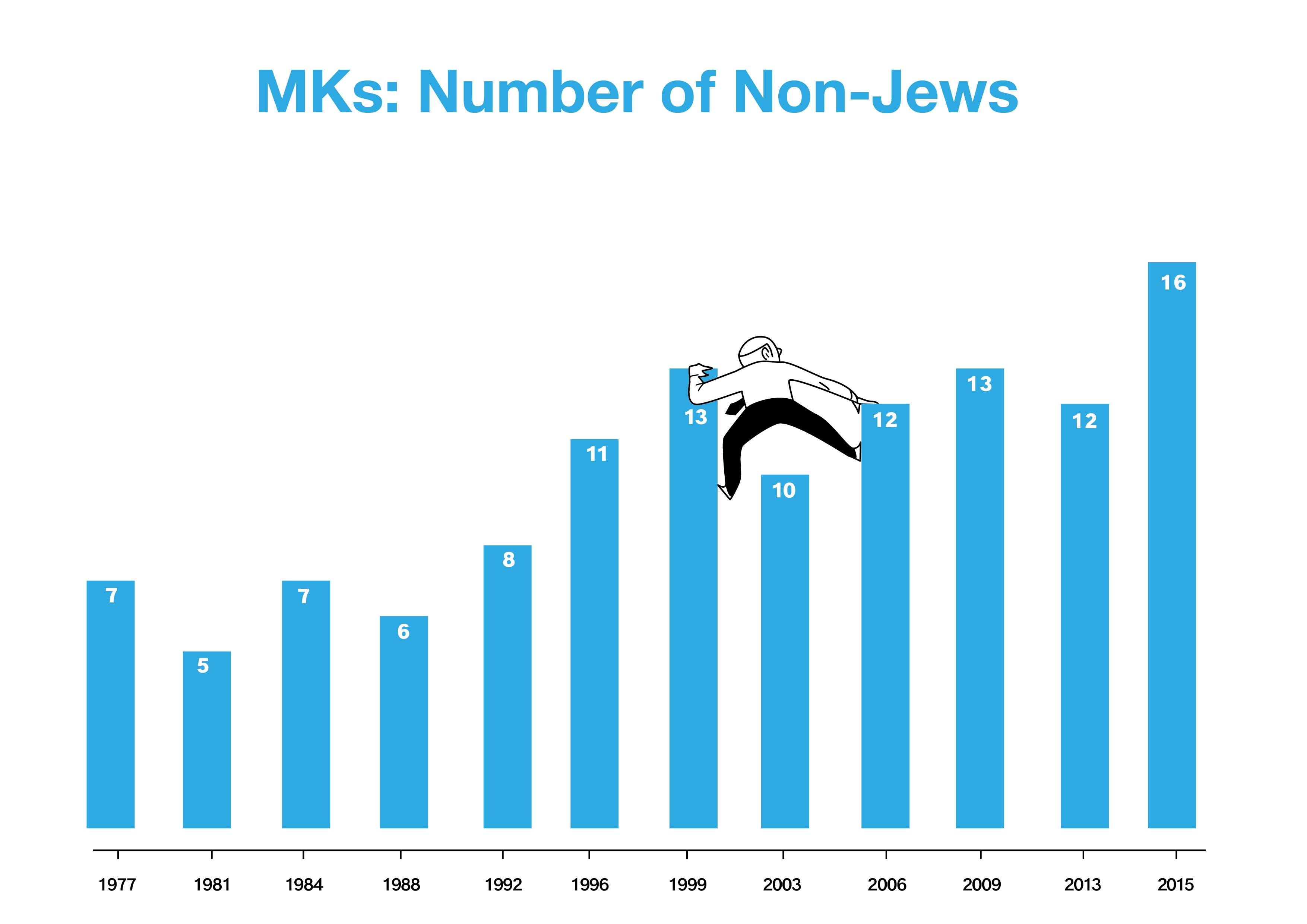

An outstanding increase in the representation of another population groups in Israel’s legislature can be seen in the non-Jewish sector (Arabs and Druze). The number of non-Jewish Knesset members was fairly small until the 1990s; it has been increasing since then and is currently at a record 16.

The explanation for this increase stems mainly from the Arab population’s transition toward voting for Arab parties, such as Ra’am-Ta’al and Balad. In the current Knesset, the Joint List, which combines the three Arab parties and Hadash, contains 12 non-Jewish members. The other four non-Jewish members are in the Likud, the Zionist Union, Yisrael Beitenu, and Meretz. Despite the increase in the number of non-Jewish Knesset members, their number is still not representative of the minority proportion in Israeli society, which is approximately 20 percent.

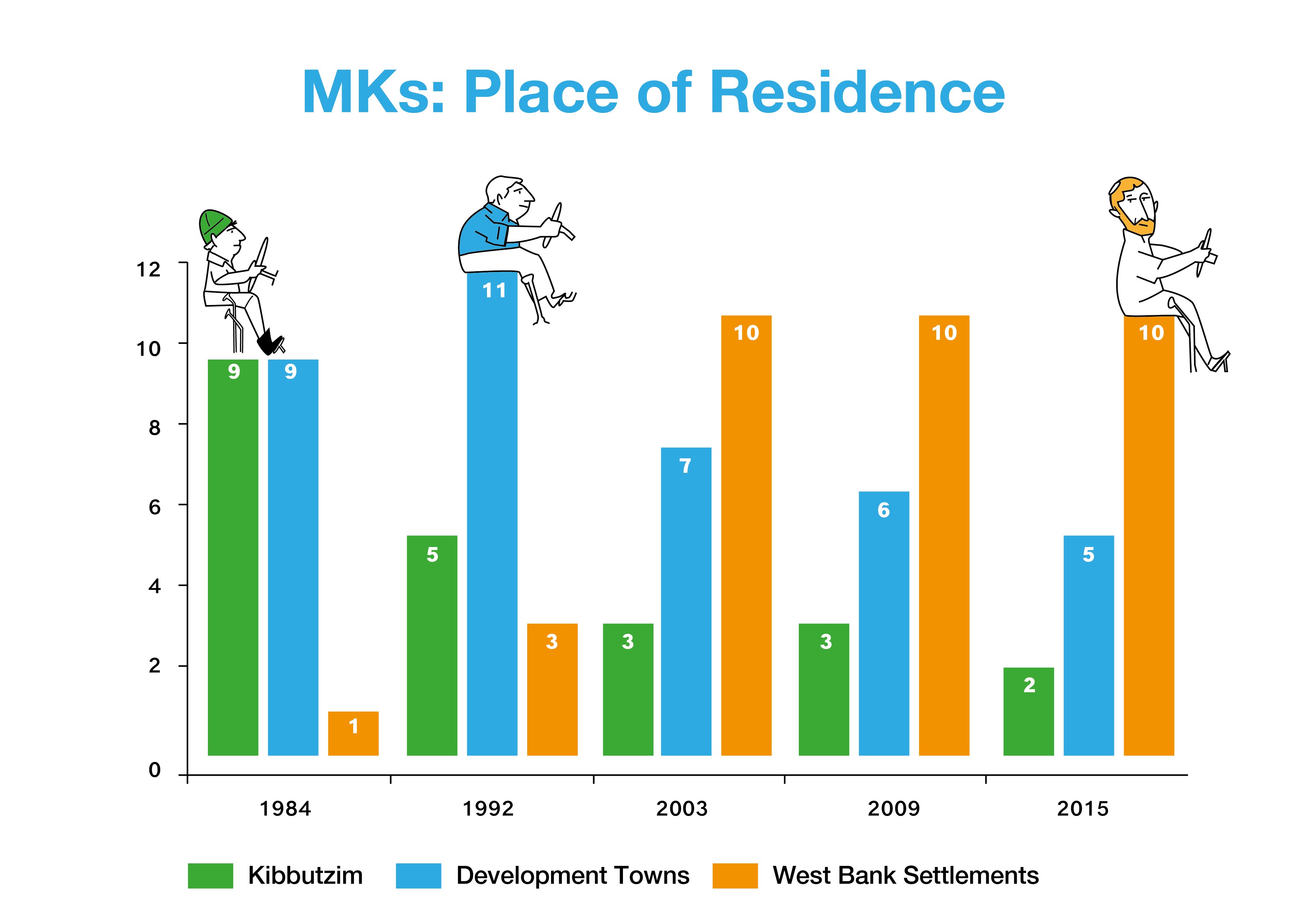

The changes that have taken place in Israeli society are also evident in the types of residential communities that the Knesset members come from. The number of kibbutznikim in the Knesset used to be much larger than their share in the population. There were 22 kibbutz members in the First Knesset, far beyond their percentage of the population. The Knesset that was elected in 1984 had nine kibbutz members. However, the number of kibbutz members has gone down significantly since then, and only two kibbutz members — Eitan Broshi and Haim Jelin — were elected in 2015.

The number of Knesset members who come from development towns has decreased steadily over the past two decades, too. On the other hand, the number of Knesset members who live in residential communities over the Green Line has increased significantly. This increase matches the significant upturn in the number of Israelis who live in that area, even if their proportion among Knesset members is still significantly larger than their share in the population.

The statistics show that Israel's current members of the Knesset constitute a group that is more in-line with the makeup of the population of Israeli society (as compared with the past). In other words, the Knesset has become less homogeneous and more varied. If, for example, we take four population groups that were considered peripheral — ultra-Orthodox people, religious people, non-Jews, and new immigrants — we find that approximately 25 Knesset members represented them in 1984, while 52 such MKs were elected in 2015.

The Knesset’s Size at a Comparative Glance

The number of members in the parliament changes from country to country according to several factors such as territory, population, and whether the government has a centralized or decentralized structure. A comparative study by two political scientists (Rein Taagepera and Matthew Soberg Shugart) examined the issue and found that the size of parliaments was expected to be the cube root of the country’s population. For example, a country with a population of one million might be expected to have a parliament with one hundred members, while a country with a population of 120 million might be expected to have a parliament with 500 members.

By this logic, the size of parliaments is not constant, but varies in accordance with demographic changes.

In Canada, for example, the number of parliament members increased recently from 308 to 338 due to population growth. The United Kingdom, Sweden, Italy, Australia, and New Zealand also increased the size of their parliaments. The number of parliament members in other countries, such as The Netherlands, Spain, Finland, and the State of Israel, has remained constant, not changing even if the population grows significantly.

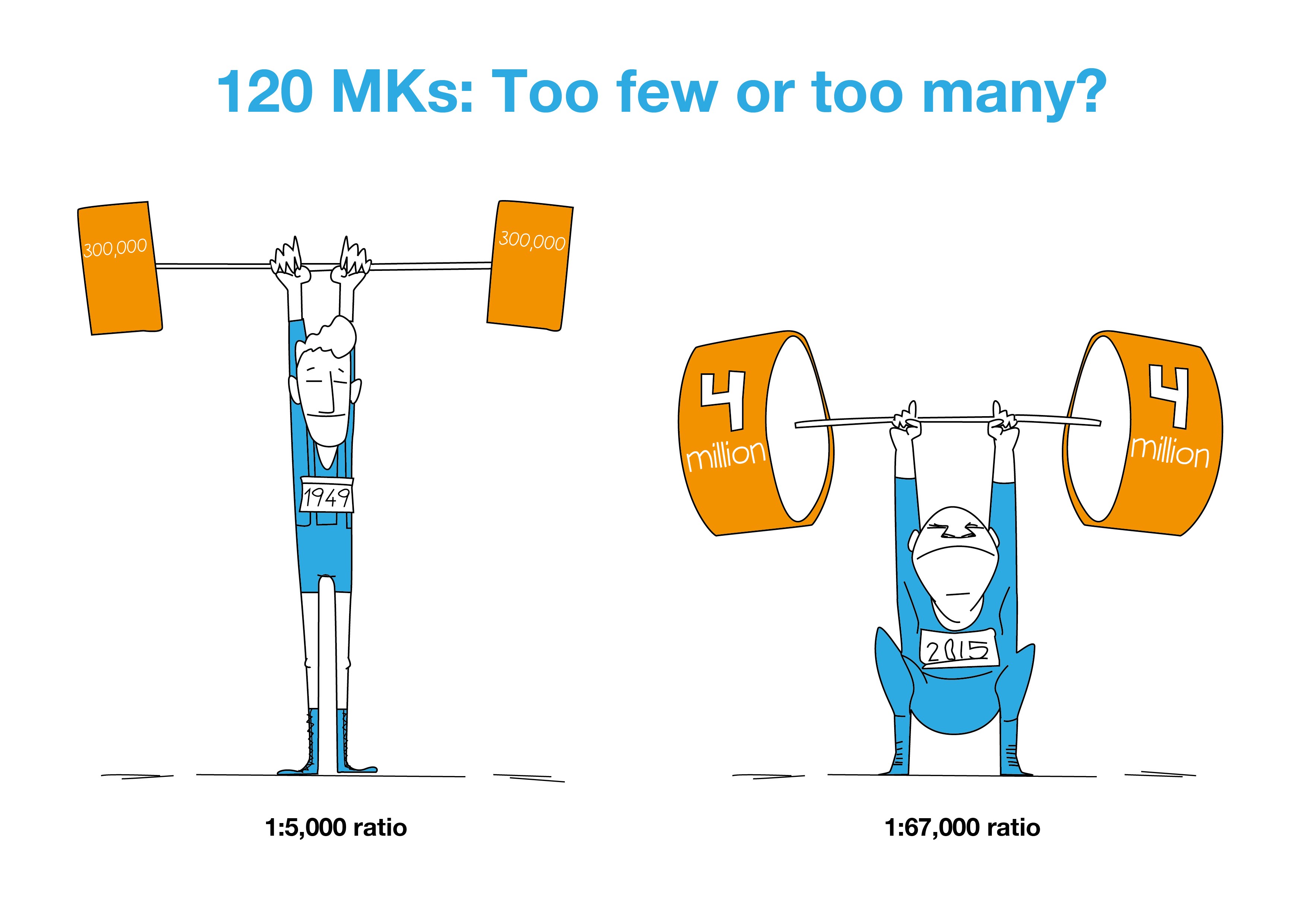

The number of Knesset members — 120 — has never changed throughout the State of Israel’s history, even through the population has increased by a factor of 13.

When the State of Israel was established, the number of Knesset members was larger than might have been expected: The cube root of 600,000 — the estimated number of inhabitants when the state was established — is 84. Currently, with a population of approximately eight million, the number of Knesset members is much smaller than might be expected, since the cube root of eight million is 200.

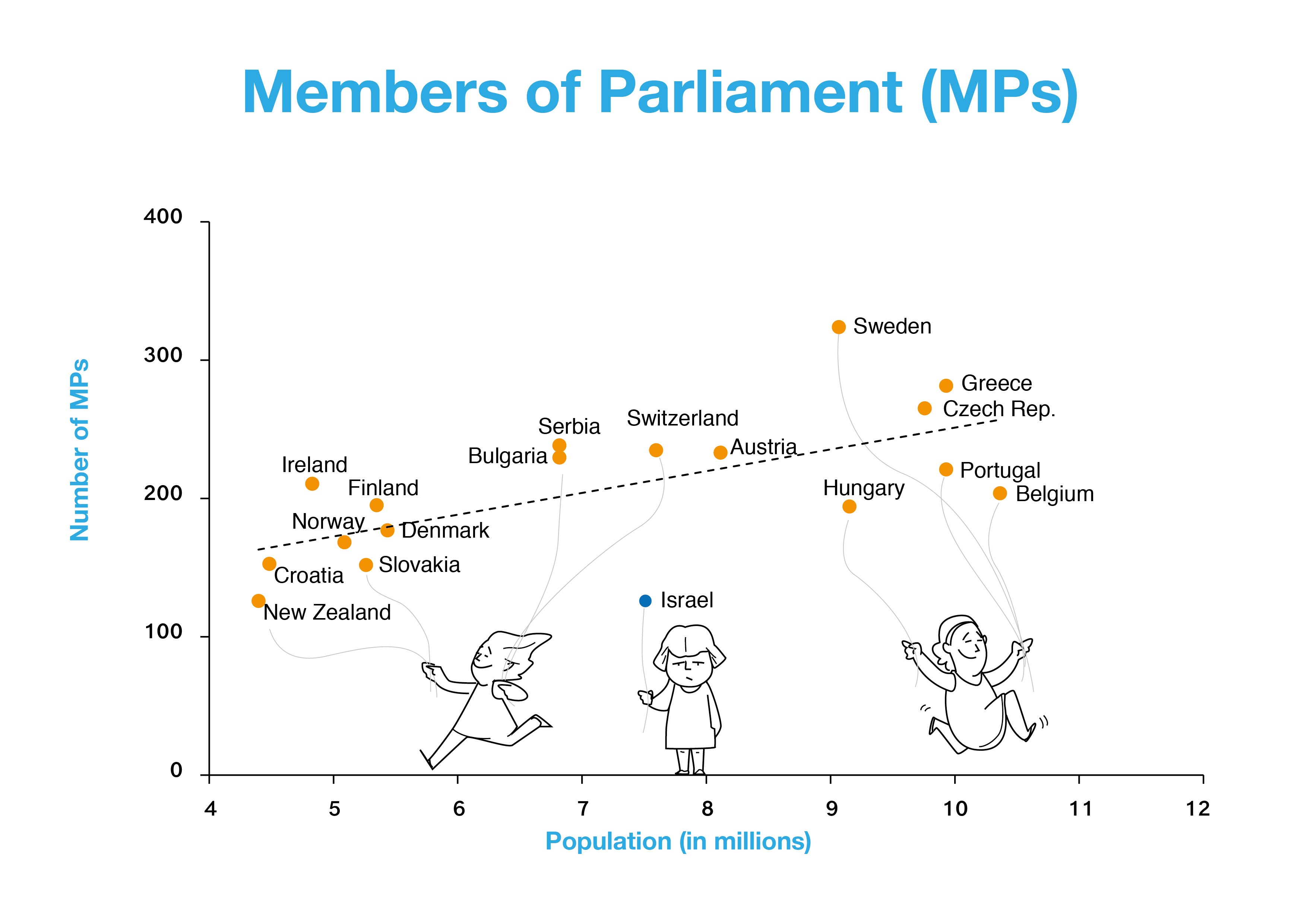

Is the number of Knesset members truly low? A glance at other countries with populations similar to Israel’s in size shows that it is. When we compare Israel to 17 democracies with populations that range between four million and 12 million people, we see that it is the farthest country from the line that shows the average. For example, New Zealand, whose population is half that of Israel’s, has a parliament the same size as the Knesset — 120 members. The parliaments of all the other countries with populations smaller than Israel’s have a higher number of members than the Knesset does.

What can we learn from this comparison? Is there any significance in the fact that our representative body is smaller than might be expected?

It can certainly be claimed that the combination of a small Knesset and inflated cabinets (a large number of ministers and deputy ministers, most of whom also serve as Knesset members) creates a situation in which the number of Knesset members who are available for parliamentary work — representing voters, working on high-quality legislation, and supervision of the executive branch — is quite small. In this way, each Knesset member serves on several parliamentary committees, which prevents him or her from acquiring expertise and becoming a professional on a particular committee. As a result, many debates are sparsely attended and proceed even though many members are missing.

This situation harms the Knesset’s potential to supervise in general, since most of the members focus is all on committees.

How can we make it better? Watch this video: