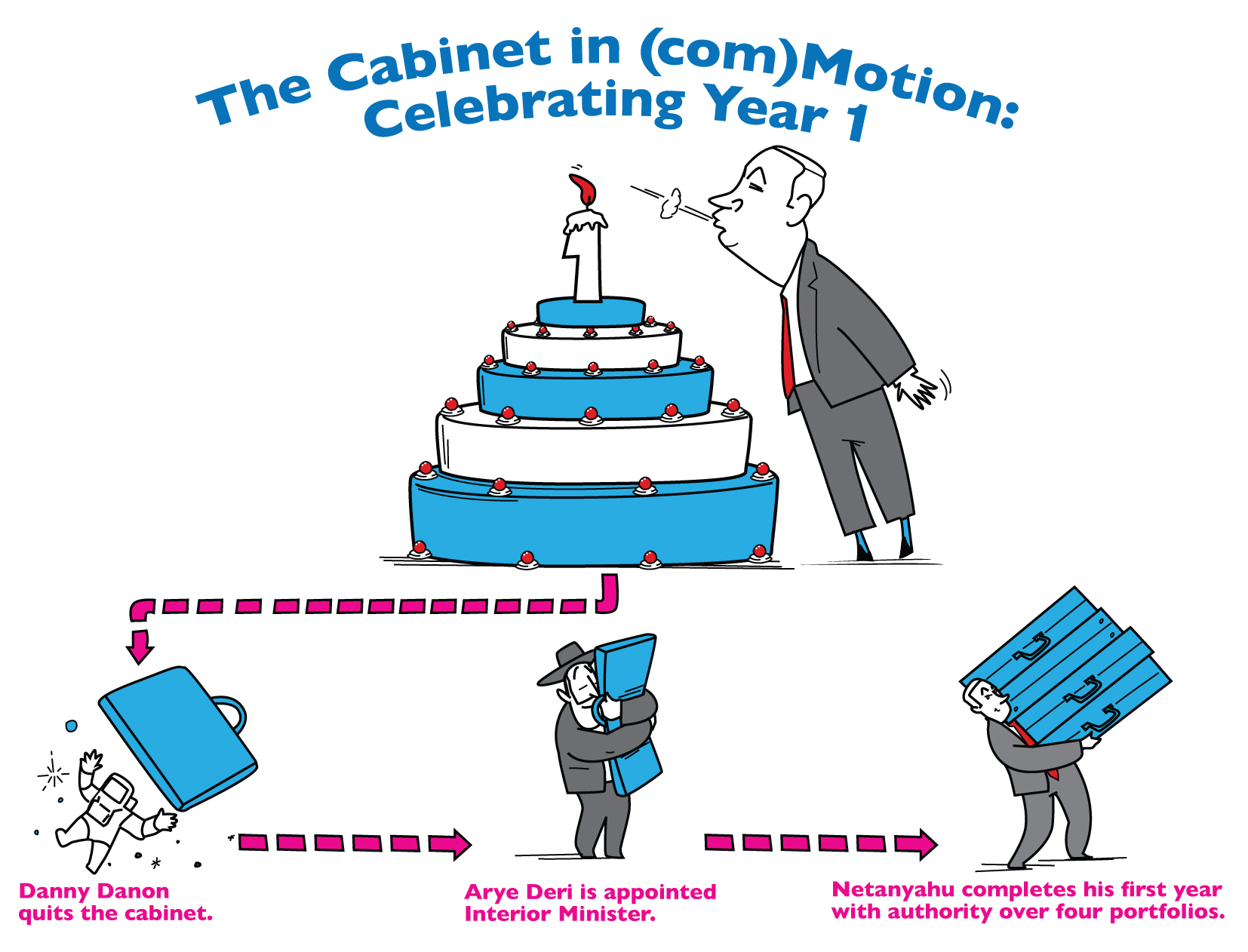

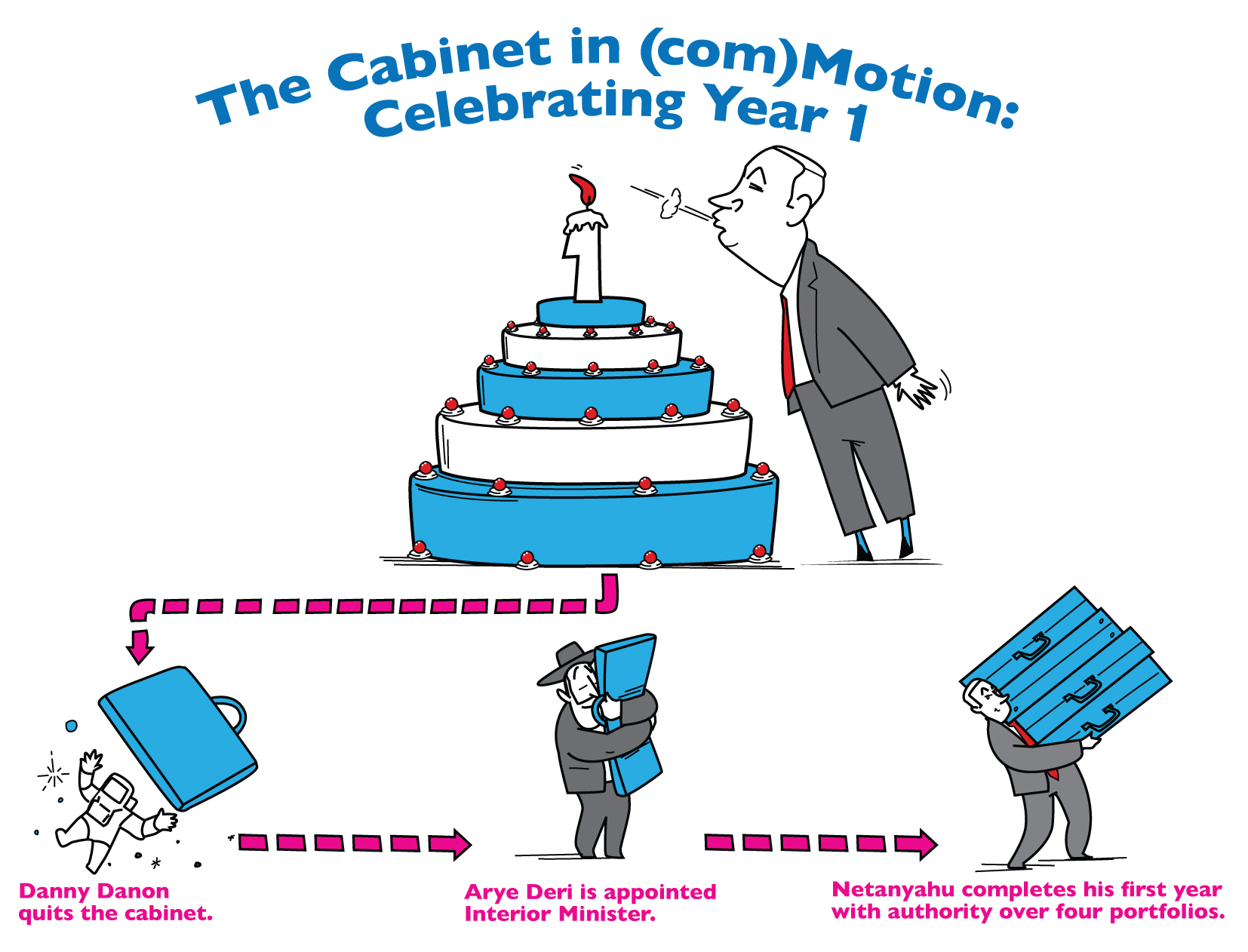

The Cabinet in (com)Motion

One Year Since the formation of the fourth Netanyahu government

As Netanyahu's cabinet approaches the end of its first year, it is safe to say it has broken a record for internal instability.

Instability in this case referring not to the danger of it breaking down – in fact it is almost impossible today to dismantle a government – but rather to the frequent changes in its composition and the structure of the executive ministries.

Within a year, nearly a third of the ministries were affected by some type of personnel and structural change. Five ministers left office for various reasons.

Each time a minister left office, the areas with which he was involved experienced some of realignment, which sometimes created a chain reaction in the personnel of other ministries.

Added to the already short terms of Israeli governments, the result is almost unbearable turnover. Since the early 1990s, the average term for an education minister is 1.8 years and for interior minister 1.3 years.

And this is only one part of the story.

The broader picture also includes the splitting of ministries, transferring of authorities from one ministry to another, and “stitching” together new ministries. Take a look at some of the bizarre ministries created in the last decade: Ministry for Regional Cooperation; for the Development of the Negev and the Galilee; for Senior Citizens; for Strategic Affairs; for Diaspora Affairs, and so on. Each of these new ministries takes over certain responsibilities from other ministries, creating instability.

Click on image to download Cabinet in (com)Motion infographic>>

Since then, these areas of governance have been split and merged between several ministries; the government treats them like Lego® bricks.

The same applies to the cluster of issues relating to industry, commerce, employment, labor and welfare. Currently, most of these areas fall under the responsibility of the Industry, Trade and Labor Ministry, at least until the projected upcoming reshuffle, which will see MK Tzachi Hanegbi (Likud) join the cabinet, replacing MK Yariv Levin (Likud) as tourism minister.

Levin will be “upgraded” to the Industry, Trade and Labor Ministry, but control over employment issues will be transferred from that ministry to the Social Affairs Ministry.

This radical instability sometimes borders on the absurd. The Authority for National Civic Service, for instance, was established in 2008 and since then has been transferred between six different ministries. Control over the Israel Broadcasting Authority passed through the hands of eight ministers in the past 10 years! Most of these changes do not result from considerations of effectiveness or broad structural reforms intended to improve the work of government.

They are rather almost always a byproduct of coalition demands and of individual/personal agendas. The result is an unbearable working environment (on both the political and professional levels) that narrows the ability to create long-term policies.

To complete this cabinet in commotion, let us not forget that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu holds, on top of his demanding job as prime minister, control over four additional ministries, which cannot possibly receive the attention they deserve.

Not to mention the existence of eight deputy ministers, further creating a circus of a system.

How did we get here? This reality stems, among other things, from a system of government that creates weak governing parties. It also suggests a political culture where personal treats and ego considerations eclipse the good of the country.

To change this, several actions should be taken. First, we should reform the political system in a manner that would strengthen the larger parties. Second, the number of executive ministries should be reduced and a core set of ministries defined. Third, the prime minister and leaders of other coalition parties must realize the damaging effect of constant change in the structure of government, and put aside ego considerations. In the end, it is to be accountable to the public for which they were elected.

The author is a researcher with the Israel Democracy Institute’s Political Reform project.

This article originally appeared in the Jerusalem Post.