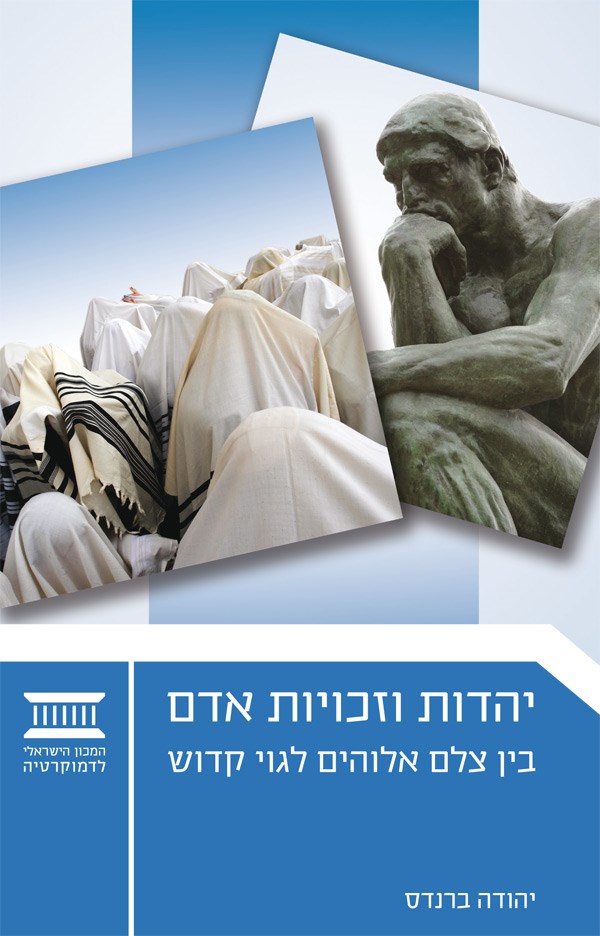

Judaism and Human Rights

The Dialectic between “Image of God” and “Holy Nation”

- Written By: Yehuda Brandes

- Publication Date:

- Cover Type: Softcover |Hebrew

- Number Of Pages: 357 Pages

- Center: Human Rights and Judaism

- Price: 88 NIS

A book by Rabbi Dr. Yehuda Brandes that explores the dialectical tension between the universal value of creation in the divine image and the particularistic value of the Jewish people as a holy nation—a tension within Judaism that is at heart of the apparent clash between Jewish and liberal values and at the core of contemporary discourse on Jewish and Israeli identity.

The definition of the State of Israel as a "Jewish and democratic" state brings into play the tension between two value systems contained within Judaism: the first is a universal approach that sees people as created in the "image of God," while the second is a particularistic, national approach that sees the Jewish people as "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." No discussion of Jewish identity can be complete without a thorough understanding of these two concepts.

In this book, which was written under the auspices of IDI's Human Rights and Judaism project, Rabbi Dr. Yehuda Brandes reviews Jewish sources from the Bible through contemporary times in order to explore these two Jewish values, which are at the heart of the apparent clash between Judaism and liberal values, and proposes a way to balance and integrate them in Israel society and the modern Jewish state. His insights can play a vital role in informing the views of Jews the world over, who grapple with the tension between the universal and particular as they straddle the different worlds in which they live.

What is the relationship between Judaism and modern discourse on human rights? The short answer to this question is that the humanistic and liberal values that underlie modern human rights discourse are not foreign to Judaism. Quite the contrary: they exist within it and emanate from it, in the Bible, halakhic literature, and modern religious philosophy.

The book of Genesis, especially the story of the Creation, is the wellspring of fundamental human principles. The creation of human beings in the image of God serves as the starting point from which primary values are derived. These include human life, human dignity, property, equality and freedom, and the family. Many precepts originate from these fundamental values.

- The value of life, first mentioned in the Bible in the verse “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed” (Gen. 9:6), leads to injunctions such as “You shall not murder” (Exod. 20:13) and “Do not stand idly by when your neighbor’s life is threatened” (Lev. 19:16).

- The principle of human dignity, which is a corollary of seeing human beings as created in the image of God, underlies the prohibitions against shaming another person, tale-bearing, and slander, as well as some of the laws related to torts and damages, the precepts that govern social relations, the obligation to respect all human beings in mind and body, and the duty to continue to show that respect after death, which is expressed in the precepts of burial and mourning.

- The value attached to property is the source of the laws of contracts and torts, the bans on robbery and theft, the laws of acquisition, land title and commerce, and the positive injunctions to build up and settle the world.

- The values of equality and freedom stem not only from the fact that all human beings were created in the divine image but also from the fact that they are all descendants of Adam and Eve; the corollaries of these values include the laws of labor relations, which mandated fair and equal treatment of workers by employers even in societies that practiced slavery, and are all the more applicable in our own day and age.

- The family is a value that derives from the simultaneous creation of the two sexes—“male and female He created them” (Gen. 1:27); from the description of marital partnership in the second Creation narrative—“ Hence a man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, so that they become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24); and from the commandment and blessing, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth” (Gen. 1:28, 9:1).

These are the underpinnings of many laws related to domestic and family law and make up the nexus of relationships within the family, between husband and wife, between children and parents, and in broader familial circles as well.

The terms “values” or “principles” should be preferred to “rights,” because the Torah outlook includes precepts and obligations. The right to life and dignity comes with a concurrent obligation to defend and respect the lives and dignity of others. In some cases, the point of departure is one person’s right; in some cases, the other person’s obligation. To put it another way, the term “values” is better because it includes both rights and obligations, without specifying a fixed and absolute primacy of one or the other.

Values require limits when the rights of one individual collide with the rights of another, or when one value clashes with another value. The book of Genesis, the Bible as a whole, and Judaism in toto incorporate not only the values that serve as the basis for culture, but also the cases in which these values are put to the test. The value of human life was violated by the first murder in history, that of Abel by his brother Cain; the value of human dignity was violated when Noah’s son publicized his father’s shame, as Noah wallowed in drunkenness in his tent after the Flood; the value of the family is put to various tests throughout the book of Genesis. The Bible is not naïve or innocent; or, in the formulation of the philosopher Emanuel Levinas, Judaism is “a religion for adults.” The Bible recognizes the existence of human needs and impulses that lead to failures to maintain these values and to guarantee rights for all. What is more, there is an essential difficulty here, which stems not from sin and evil but from the natural and inevitable confrontations between the values and rights themselves.

Dealing with the contest between competing rights and values of individuals and human societies, requires the application of tools for rendering decisions in situations that are questionable. The characteristic instrument developed by the Oral Law for this purpose is Halakhah. Halakhah is supposed to provide the rulings when values collide. For example, the deliberations about the value of life include the dictum “your life takes precedence over the life of your fellow,” which is to be applied when you have insufficient resources to keep both of you alive. They also include the principle of “if someone comes to kill you, strike first,” which is applied to situations in which protecting the life of someone who is threatening your life would endanger your own life. Beyond the general dicta, there are also the minute details of changing circumstances—questions of endangering oneself in order to save another, using force to prevent harm to a third party, abortion, organ donations, and more. In all these cases, the halakhic discourse is based, explicitly or implicitly, on the fundamental principle of human life: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed.”

The universal dimension of the Torah is found in the book of Genesis, which contains ethics that were given to all human beings descended from Adam and Noah. This constitutes the ground floor, the basic values of the Torah and Judaism, parallel to the modern system of human rights and hardly different from it in any essential way. The next level, designated “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:6), represents the dimension of the selection of Israel to bear a special divine mission. Of Abraham we read, “For I have singled him out, that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is just and right” (Gen. 18:19). His reward was honor and blessing: “All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants” (Gen. 28:14). Before the Israelites received the Torah at Sinai, we learn that the purpose of this gift was to make them into “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”

The concept of a “kingdom of priests and holy nation” obligates the Jewish people to observe an additional and much broader set of precepts than the basic and universal code constituted by the “Seven Noahide Commandments”; even though this code actually encompasses much more than seven precepts, the Torah imposes on the Jewish people an extremely comprehensive canon of statutes that are not incumbent on other nations. The notion of the added sanctity of the Jewish people, which accompanies the supplementary precepts, rights, and obligations that apply only to them, undermines the principle of equality—not only by creating a distinction between Israel and the nations, but also by introducing gradations within the Jewish people, as, for example, between the kohanim of the priestly caste and other Jews (“Israelites”), or between men and women.

This volume takes a comprehensive look at the concept of the holiness and election of the People of Israel as God’s “chosen people” and at its implications for the doctrine of human rights. It begins by elucidating the nature of the relationship between the Jewish people and the nations of the world. At one extreme, we find pronouncements that express scorn and revulsion about the nations of the world in general and about idol worshipers in particular; at the other extreme are statements about the value of human beings as such, which ground the very existence of humanity. Here too, the role of Halakhah is to chart a balanced course between the poles of this tension.

But another element, which is historically important, enters into any discussion of the relations between Israel and the nations. The debate is not purely theoretical and theological, with no cultural, social, and historical contexts. The bloody history of anti-Semitism over the ages has left its mark on Jewish thought and Halakhah and has deeply impaired the Jews’ trust in the humanity of the descendants of Noah. Many of the conceptual and halakhic positions that distinguish and limit the Jews to their own domain, while expressing fierce antipathy to the nations around them, are the result of the bitter historical experience and not of the ideal theory propounded by the Torah. In other circumstances, peering out between the lines of Halakhah we can see an approach that preserves the humanistic side of relations to humanity at large.

The discussion of the “kingdom of priests and holy nation” goes on to examine the challenges that the awareness of holiness poses for the discourse of human rights and values. For example, the value of human life must yield to the precept of sanctifying the divine name. The circles of holiness create distinctions and hierarchies among human beings: between Priests and Levites and Israelites, between Jews of impeccable lineage and converts or those whose lineage is flawed, between men and women, between those who are whole of body and those with disabilities. The value of dignity is set aside for a number of precepts: We are not required to honor our father and mother if they tell us to transgress a commandment. The value attached to intimate relationships and marriage must give way to the prohibitions related to forbidden unions and holiness: the ban on a kohen’s marrying a divorcee and the problematic status of agunot (wives whose husbands have disappeared), mamzerim (the children of forbidden relationships), and mesoravot get (women whose husbands refuse to give them a divorce) are examples of situations in which the notion of the sanctity of marriage takes precedence over the discourse of the right to participate in an intimate relationship. The two tracks are presented not as merging but as colliding—the track of the “image of God,” which is the basis of human rights, and the track of “a kingdom of priests and holy nation,” which constrains and limits universal human values.

How do the Torah and Halakhah deal with the tension between these two tracks or two opposing systems for living? The fundamental axiom is that we are not dealing with tension and contradiction between the Torah and some external and alien culture, but with an internal tension that stems from the existence of two principles that coexist within the Torah itself. Dealing with and resolving these two opposing poles is the very soul of talmudic thought. It is based on the notion that “both these and those are the words of the living God” (BT Eruvin 13b): both of these contradictory positions are valid and true, and no final and absolute decision can be rendered in favor of one or the other. The disagreement will persist and any decisions will apply only to particular cases, as a function of the circumstances. Some are one-time rulings, while others remain in force for generations. This is the art of halakhic ruling as practiced by the rabbis, who have at their disposal a set of substantive and procedural tools for determining the practical Halakhah in cases of disagreement, doubt, and conflict.

A typical example of this is the tension between humanity and nationalism, which can be found in philosophy, Halakhah, and even the liturgy. For example, Jewish prayers and blessings are full of references to the unique status of the Jewish people—“Who selected us from among all the nations” (the blessing on the Torah)—alongside abundant hopes and prayers for all humankind—“when all humanity will call on Your name” (from the daily prayer Aleinu). The dialectic of values is manifested in specific halakhic issues: it is forbidden to steal from non-Jews, but one need not return lost property to them—although in certain circumstances the injunction to restore lost property to non-Jews is given greater weight than the command to restore such property to a Jew. Distinctions are drawn between “repulsive idolaters” and “nations who live according to ethical laws.” The nature of the relationship between Jews and these types of people fluctuates in response to historical and cultural circumstances. The dialectic approach does not support the idea that humanistic values are meta-halakhic principles that influence halakhic decision-making, as is sometimes stated in works on the philosophy of Halakhah. In my view, universal humanistic values are part and parcel of authentic and original Jewish thought and Halakhah. Their fruitful and challenging encounter with the principle of the holiness and uniqueness of the Jewish people is worked out through the practical, concrete, and detailed efforts that are typical of halakhic discourse from the talmudic age to the present.

As in every generation, contemporary Jewish and Israeli society is called upon to find anew the appropriate equilibrium between the universal and the particular, between the human race and the nation. The establishment of the State of Israel and its definition as a Jewish and democratic state place the challenge of dealing with the dialectic of “holy nation” and “the image of God” at the center of discourse about Israeli and Jewish identity today.

Rabbi Dr. Yehuda Brandes is a research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, head of the Beit Midrash at Beit Morasha – The Center for Advanced Judaic Studies and Leadership in Jerusalem, and a lecturer at Herzog College.