Presentation of the 2013 Israeli Democracy Index

The President's Residence

Jerusalem

Participation by invitation only

How do Israelis assess the government's ability to deal with challenges? Do they have confidence in their elected officials? On Sunday October 6, 2013 at 10:30 a.m., IDI President Dr. Arye Carmon presented the 2013 Israeli Democracy Index to President Shimon Peres at a ceremony at the President's Residence.

Headed by Prof. Tamar Hermann, Director of IDI's Guttman Center for Surveys, the annual Israeli Democracy Index has been the leading barometer of perceptions of the quality of Israeli democracy since its first publication in 2003. Based on an extensive survey of a representative sample of the adult population in all sectors of Israeli society, the report provides critical insights regarding trends in public opinion regarding the preferred form of government, the functioning of the political system, the behavior and performance of elected officials, and the realization of key democratic values. Analysis of its results may contribute to public discussion of the status of democracy in Israel and create a cumulative empirical database to intensify discourse concerning such issues.

In 2013, as in previous years, the Israeli Democracy Index seeks to examine the institutional, procedural, and perceptual aspects of Israeli democracy. The purpose of the report is to provide a comprehensive, up-to-date portrait, and at the same time identify trends of change and elements of stability in Israeli public opinion in the political and socioeconomic spheres. Readers should bear in mind, however, that the survey on which the Index is based measures the feelings, opinions, and judgments of the general public, meaning that this is not an "objective" or professional assessment of Israel's situation. Inevitably, the public sees things in a way that may prove in future, or even at present (in the opinion of experts), to be inaccurate or imprecise. Nevertheless, perceptions, attitudes, and emotions play a major role in the public's behavior (including its electoral preferences), making it eminently justifiable in our view to invest effort and resources in exploring them.

The Israeli Democracy Index 2013 is divided into five chapters:

- How is Israel Doing? – Background showing the distribution of opinions on Israel's overall situation and Israeli democracy today.

- The Political System

- Source of Authority: Religion or State?

- Citizens, the State, Politics, and Society

- Israel 2013: An International Comparison – Israel's ranking on 13 democracy indicators, as compared to 27 other countries and Israel's own placement in previous years.

The questionnaire for the 2013 survey was developed in February–March 2013, and data were collected by the Dialog Institute via telephone interviews between April 8 and May 2, 2013. The questionnaire was translated Russian and Arabic, and the interviewers who administered these versions were native speakers of these languages. A total of 146 respondents were interviewed in Arabic, and 102 in Russian. The survey included 200 cellular phone users, primarily to offset the difficulty of obtaining responses from young people using a landline.

The study population was a representative national sample of 1,000 adults aged 18 and over (852 Jews and 148 Arabs). The sampling error for a sample of this size is ±3.2%. The survey data were weighted by sex and age.

How is Israel Doing?

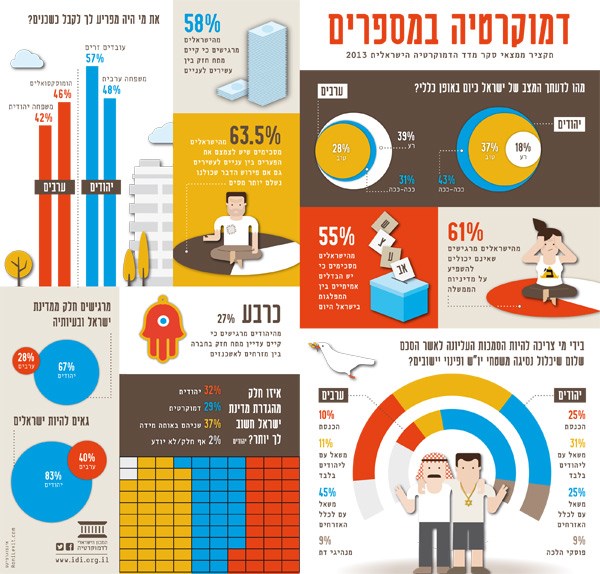

- The Overall Situation – Jewish Israelis most frequently assess the country’s overall situation as “so-so” (43.1%), with 36.7% labeling the situation “good” and 18.4% considering it “bad.” By contrast, a plurality of Israel’s Arab citizens assess the situation as "bad" (39.1%), followed by "so-so" (30.8%), and "good" (27.6%).

- Belonging and Pride – 83.3% of Jewish Israelis are proud to be Israeli and 66.6% feel part of the state and its problems. Among Arabs, only a minority (28.2%) feel pride in being Israeli (39.8%) or a sense of belonging to the state (28.2%).

- Democratic Rights – 41.8% of Israelis feel that the right to live with dignity is upheld “too little” or “far too little” In Israel. The prevailing opinion is that freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom of assembly are upheld “to a suitable degree.”

- Socio-Economic Gaps – A majority of Israelis (63.5%) agree that it is important to narrow the socioeconomic gaps in Israeli society even if it means paying more taxes.

The Political System

- Public Confidence – The 2013 survey showed a slight decline in the level of trust in all state institutions and public servants. As in the past, among Jewish respondents, the Israel Defense Forces (whom 90.9% regard as trustworthy) and the President of Israel (78.7%) top the scale. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court (49.7%) and the media (48.1%) rank highest among Arab respondents.

- Motivation of Leaders – While the assessment of Knesset members’ performance has improved somewhat, a clear majority of Israelis (68.8%) still feel that politicians are more concerned with their own interests than those of the public.

- Impact of Voting Patterns – Voting patterns in the 2013 Knesset elections turned out to have little value in predicting opinion on the issues, underscoring the tenuous status of political parties as political “indicators.” Nonetheless, a majority of respondents (55.3%) perceive differences among the parties and believe their choice among them matters.

- Electoral Reform – A majority of Jewish respondents (67.8%) think it would be better to have a few large parties rather than many small ones. Arab respondents were split evenly on this question.

- Political Interest and Impact – A majority of Jewish respondents (71.8%) reported that they are interested in politics. By contrast, most Arab respondents (59.6%) reported that they are not interested in politics. In both groups, a majority (61%) feel that they have little or no ability to influence government decisions.

- Use of Political Violence – The majority of both Jewish (74.6%) and Arab (67.1%) citizens of Israel are opposed to the use of violence for political ends.

- Refusal of Orders – A majority of Jews in Israel (62.8%) feel that soldiers do not have the right to refuse to serve in the West Bank on the grounds that they oppose the occupation. Just over half (50.9%) think soldiers do not have the right to disobey an order to evacuate settlements either. A majority of the Arabs support the right to refuse orders in both cases.

- Patriotism/Nationalism – The survey findings indicate that, in general, younger Israeli Jews are more patriotic and nationalist than their elders.

Jewish? Democratic? Jewish and Democratic?

- Israel's Dual Identity – A sizeable majority of Jews (74.8%) believe that the State of Israel can be both Jewish and democratic. Only a third of Arab respondents share this view.

- Jewish or Democratic? – Roughly one-third (32.3% ) of the Jewish respondents think the Jewish component of Israel's definition as a Jewish and democratic state is more important, while 29.2% attach greater importance to the democratic component. The percentage of respondents who prefer the combined definition “Jewish and democratic” has declined steadily in recent years, reaching 37% this year.

- Halakha vs. Democracy? – The share of Jewish respondents who would choose democratic principles over Jewish religious law (halakha) in the event of conflict between the two (42.7%) clearly outstrips those who would favor Jewish law in such a situation (28.2%).

Jews and Others

- Rifts in Society –The overall sample (68%) sees the rift between Jews and Arabs as the greatest area of friction in Israeli society. This is followed, in descending order, by tensions between rich and poor, the religious-secular divide, differences between right and left, and friction between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim.

- More Rights for Jews? – Jews are split over whether Jewish citizens of Israel should have more rights than non-Jewish citizens: 48.9% agree with this notion, while 47.3% disagree.

- Attitudes Toward the "Other" – When it comes to having “others” as neighbors, Jews expressed greatest aversion to living next to foreign workers (56.9%), followed by an Arab family (47.6%). Arabs expressed greatest aversion to having a homosexual couple as neighbors (46.2%), followed by a Jewish family (41.9%).

- Arab Emigration – This year saw a decline in the share of Jews who support government policies that encourage Arabs to emigrate: 43.8% favor such policies, as opposed to 50.7% in 2010 and 53.6% in 2009.

- A Jewish Majority for Critical Decisions? – Most Jewish respondents feel that critical national decisions should be determined by a Jewish majority, both on matters of peace and security (66.7%) and on social/economic issues (56.9%). A majority of Arab Israelis disagree.

- A Peace Treaty Referendum? – On the question of who should have the final authority to approve a peace treaty that includes withdrawal from the West Bank, the prevailing response among Jews (30.6%) was that only Jewish citizens should decide the issue by referendum. Among Arab respondents, the most frequent response (45.2%) was that all Israeli citizens should determine the outcome by referendum.

How Does Israel Compare with Other Countries?

- Overall Standing – This year's annual international comparison did not reveal significant changes in Israel’s position vis à vis the world’s democracies. In most international indices, Israel falls at the midpoint of the scale, adjacent to the new democracies.

- Strengths and Weaknesses – Israel scored especially high this year in political participation, and received particularly low grades for civil liberties and religious and ethnic tensions.

The 2013 Israeli Democracy Index points to a number of interesting trends in Israeli public opinion on issues related to Israeli democracy:

- Overall findings – Despite surprises in the 2013 elections, and far-reaching changes in the government's makeup, the outcome of the vote did not lead to major swings in public opinion on the topics examined in the survey. In most cases, there were moderate shifts relative to previous years. In areas where changes were identified—for example, a slight improvement in the perception of politicians as hard workers who are doing a good job or a greater belief in the political influence of citizens—further studies are needed to determine, with an appropriate level of validity, whether there is a real change in public opinion and awareness. These indications of opinion stability are highly important, given the common assertion of the media and certain decision makers that public opinion is constantly spinning in different directions. In fact, in the analysis below, clear and consistent connections can be found—not for the first time—between the opinions of respondents on democracy-related issues and background variables, such as national identity (Jew, Arab), level of religiosity, self-identification with stronger or weaker social groups, and self-described location on the left-right spectrum of political and security affairs. It is therefore obvious that these are not random associations but deeply rooted worldviews that are difficult to manufacture or manipulate politically without a genuine shift in the reality of the respondents.

- "New politics" – The proximity of the survey to the 2013 elections, and their dramatic results raises the question of whether the public believes that a new politics is emerging in Israel, and if so, what they think of it. Although the "new politics" is generally seen as a positive phenomenon (we identified eight subcategories of this favorable attitude), only a small majority of the public believe that the recent elections were in fact a reflection of a new politics. Among the weaker or excluded groups (low-income individuals, Arabs, those who identify themselves with weak social groups, and so on), the share who believe that the outcome of the recent elections signals a new politics is undeniably low. This means that those in the weak/excluded groups do not expect that the results of the 2013 elections will solve their problems.

- Israel's overall situation – Contrary to the common portrayal in the media, the Jewish public (and thus the total sample, since Jews constitute a majority of the sample, in accordance with their proportion of Israel's population) tends to assess the country's overall situation as average ("so-so"); in other words, the situation in Israel is not glowing, but is not dismal either. In this area, there is virtually no change from last year's findings. By contrast, Israel's Arab population—always a minority whose long-term status is not secure (see below)—tends to define Israel's situation in more negative terms, though here too we found a strong inclination toward the middle response. The group that clearly sees the situation as less good is the younger age cohort; the bad news for those who expect this to spur young people into action, however, is that there is no evidence in the survey to suggest that this group wishes to shake up the system or even challenge its basic elements in order to generate change from the ground up.

- The younger age cohort – A salient finding throughout the survey is the greater tendency of Jewish respondents in the younger age cohort to express views ranging from patriotic to nationalistic compared to the older age groups. One explanation for this is the greater presence of religious and haredi Jews in the younger age cohort because of the higher birth rate among these groups and because these groups more than the other groups tend to espouse patriotic/nationalistic views. Nonetheless, the finding can be attributed to more than demographics. Young Jews—to the chagrin of some and the satisfaction of others—are perhaps slightly less "political" than their elders (i.e., less interested in politics), but they are unquestionably more "Jewish-patriotic" and as a generation they desire a more "Jewish" state. At the same time, their commitment to democratic values—again, as an age group and not necessarily as individuals—is less than their parents' or grandparents' generation.

In many other respects, the younger age group is quite similar to the other cohorts, such that it appears that their degree of conformity with mainstream Israeli-Jewish society is high. Due to the small size of the Arab sample (which parallels the proportion of Arab citizens in Israel's adult population at 15%), it is difficult for us to draw conclusions about the views of the younger Arab age group with certainty. However, as detailed in the report, there are some signs here and there that members of this age cohort also conform quite strongly to their group of origin, although they have a more noticeable tendency than older Arab adults to express dissatisfaction with, and alienation from, the state. - The state of Israeli democracy – Assessments of the state of Israeli democracy were found to be less favorable. The responses to the survey indicate that the chief failing concerns the right to live with dignity. With respect to democratic values such as freedom of religion and freedom of expression and assembly, the situation is seen as appropriate.

- Being part of the state – Regarding estrangement from the State of Israel, and conversely, pride in being Israeli, the survey findings do not support the bleak picture common in Israeli discourse. There is, indeed, a small but steady decline in the general public's feeling that they are part of the state and its problems, and there is a similar decline in the sense of pride in "Israeliness." With respect to the Jewish public, this is a slight drop; the vast majority still feel themselves to be part of the state and its problems and are proud to be Israeli. By contrast, only a minority in the Arab sample report feeling part of the state and its problems, and pride in being Israeli is quite low. Stated otherwise, this is a population that does not feel "at home" in its Israeli citizenship, which should come as no surprise, since Israel defines itself as a "Jewish and Zionist" state. What is more, the Jewish majority generally expresses a readiness to exclude Arab citizens from decision-making in crucial matters (see below), and has a growing desire, particularly among young adults, for the state to be seen as more Jewish and less democratic.

- Influence of voting patterns – Of particular interest in this year's survey is the finding that voting patterns in the 2013 Knesset elections are not a good explanatory variable for differences in the respondents' positions on major questions. That is to say, on many key topics there are no significant differences between the views of voters for one party and another, and there is no consistent similarity between the opinions of respondents who voted for the same party. Moreover, even on questions where we would expect to find differences between the views of voters for parties in the government and voters for parties in the opposition, significant differences were not found. The resulting conclusion is that voting in Israel in 2013 does not reflect a clear worldview, that voter identification with parties is weak (hence the party's positions on foreign and domestic issues are not variables that shape voters' opinions), and that the parties do not serve as political "oracles" for their voters, meaning that the views expressed by party leaders are not ideologically binding—even for their own voters.

- Explanatory variables – In this survey, as in the past, the so-called "classic" explanatory variables—such as sex, ethnic origin, education, income, and often, age and voting pattern—were shown to have little or no effect on the views of the Israeli public. The variables in 2013 that were found to be particularly influential are tensions between Jews and Arabs, the division between religious and secular Jews, and the differences between right and left on political/security issues. This is in contrast to the right-left division in the economic sphere which was found to have negligible influence because the Israeli public tends to cluster in the middle of the spectrum around the notion of a welfare state, and rejects both socialism and a totally free market.

- The Jewish-Arab divide – The greatest share of respondents identified the tension between Jews and Arabs as the most serious area of friction in Israeli society. In topics related to the relations between Jews and Arabs, we found trends that are seemingly paradoxical and even contradictory. One phenomenon is the increased preference among the Jewish public for either the "Jewish" or the "democratic" component in the definition of the State of Israel, alongside a drop in preference for the combined definition of "Jewish and democratic." Likewise, we found a clear willingness to make Jewish halakhic law (mishpat ivri) the cornerstone of the Israeli legal system. A small majority of Jews also favor government backing for the establishment of new communities throughout the country, (by Jews only, not by Arabs). However, only a minority support the third element of the draft bill "Israel: the Nation-State of the Jewish People," namely, revoking the status of Arabic as an official language of Israel.

While this year there is a decline in the share of Jews who believe that the government should encourage Arab emigration from the state, the Jewish public is divided as to whether Jewish citizens should be given more rights than non-Jewish citizens. The fact that roughly half of the respondents consider the latter to be an acceptable policy is extremely problematic in terms of democracy, since the essence of democracy is the principle of equal rights for all citizens and this principle is enshrined in Israel's Declaration of Independence.

It should be noted in this context that while a decline was recorded this year in the share of Jewish respondents who hold that decisions crucial to the state in matters of peace and security, and society and economy, must be made by a Jewish majority, a large proportion of the Jewish sample believe that Arabs should not take part in a referendum to approve a peace treaty with the Palestinians, if and when such a referendum is held.

The survey also reveals that a majority of the Jewish public considers the Jews to be the "chosen people," and that there is a direct correlation between this view and support for excluding Arabs from a possible referendum. This leads us to conclude that this sense of "chosenness" entails the exclusion of others.

Notwithstanding the above, the fact that the largest share of respondents sees Jewish-Arab tensions as the major type of tension in Israeli society takes on a slightly different cast if we consider the following: whereas in the past, when Jews were asked which type of "other" they would not like to have as a neighbor, they indicated that they would be most bothered by having Arabs as neighbors, today they would be more concerned about living in proximity to foreign workers, with Arabs dropping to second place. Arabs are most disturbed by the prospect of living next to a homosexual couple; having Jewish neighbors now ranks second. - Perceptions of willingness to compromise – The question of how much "others" are willing to compromise in the name of coexistence was instructive in terms of how groups in Israeli society view each other. We found that Arab respondents believe that Jews are willing to compromise more than Jews believe the same about the Arabs. Religious Jews hold that secular Jews are more willing to compromise than the converse, and people on the right feel that people on the left are more open to compromise than people on the left feel about the right. All of this, of course, affects each group's assessment of its chances to advance its status within the existing power relations of Israeli society.

- Political institutions – As we do every year, we examined the image of politicians in the eyes of the public, and the degree of trust in the institutions of the state. While the majority of respondents feel that politicians are more concerned with themselves than with the public, there has been a certain upswing in the assessment of the performance of politicians and in the perception that Knesset members are generally working hard and doing a good job; however, understandably perhaps, there is nostalgia for the politicians of yesteryear. In addition, we found a slight downturn in the public's trust in most of the state and political institutions that were studied, as well as in all holders of public office. Not surprisingly, data indicate a clear difference between the levels of trust of the Jewish and Arab populations. Most Arab respondents—in keeping with the feelings of alienation noted above—do not have trust in any of the political institutions or officeholders in Israel.

- Political parties – Despite the very low level of trust in Israel's political parties and the fact that voter preference does not appear to play a significant role in shaping public opinion on political issues, it is important to note that the majority of those surveyed hold that there are genuine differences between the parties and their vote matters. The majority of respondents are also interested in reducing the number of parties in Israel, and would prefer a few major parties to the numerous small parties in Israel today.

- Influence on policy – We found a certain increase this year in the feeling that citizens are able to influence political decisions. This feeling, however, is still very low compared with what is expected from a democratic country. It seems that the majority of both Jews and Arabs feel unable to influence government policy or impact the decision-making echelon.

- International indices – The annual international comparison did not reveal anything exceptional. As was found last year, in most international indices Israel is located roughly at the midpoint of the scale, adjacent to the new democracies. Israel scored particularly high in political participation, and received low marks for civil liberties and religious and ethnic tensions.

The Israeli Democracy Index 2013 (English)

The Israeli Democracy Index 2013 (Hebrew)

Main Findings: The Israeli Democracy Index 2013 (English)

SPSS File

To access the Israeli Democracy Index of previous years in both Hebrew and English, click here.