A Suggested Moral Analysis of the Goldstone Report and its Aftermath

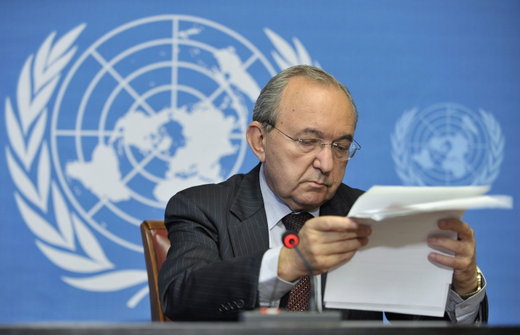

In this article from JUSTICE Magazine, Prof. Mordechai Kremnitzer, IDI Vice President of Research, analyzes fundamental principles that bear crucially on the moral aspects of the Goldstone Report, Israel's stance with respect to the report, and contemporary international criminal law in general. Reprinted with permission, the article is based upon a presentation made to a conference of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists in London on July 1, 2010.

Introduction

I propose to set out here a few fundamental precepts which, to my mind, bear crucially on the moral aspects of the Goldstone Report,Report of United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, "Human Rights in Palestine and Other Occupied Arab Territories," UN Doc. A/HRC/12/48 (Advanced Edit Version, 15 September 2009) (hereinafter: Goldstone Report or Report) available at www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/specialsession/9/docs/UNFFMGC_Report.pdf (last visited 4 October 2010) Israel's stance with respect to it, and more broadly to international criminal law today.

The Requirement of a Factual Basis

My first proposition is that findings that assign moral or legal responsibility, even if tentative and preliminary (but serious enough to justify a demand for further investigation), must have a basis in fact. The Goldstone Report dealt with a military combat operation and purported to reach initial findings of this sort, findings that attributed horrendous criminal intentions and acts to Israel's political and military echelons. It did so with no demonstrable basis in fact to support the findings. Israel refused to provide the Goldstone Commission with its own version of the Cast Lead operation, and it is not my intention to pass judgment on that decision. Regarding Palestinian evidence as well, the commission itself wrote that witnesses were reluctant to speak about military operations by Hamas. The result was that those who drafted a report on a military operation did so without any notion of the nature of the military actions that took place in that operation. What were the goals set for these actions, and what means were used to achieve them? What risks were taken into account beforehand, and what were the real risks faced by IDF soldiers once the operation got under way? Without answers to these questions, no conclusions can be drawn about the proportionality of the actions taken by the IDF, and certainly not about any criminal intent behind these actions. Without a minimal basis in fact, the Report's findings are of no value.

No factual basis of any value can be achieved without a suitable investigation. This logic applies to Israel as well. Israeli citizens will never know which option was preferable: ending Operation Cast Lead after three days, for humanitarian reasons, as the minister of defense recommended, or prolonging it for an additional 17 days, as was actually done. The reason is that the Israeli government refused to appoint an independent, autonomous commission to investigate the war. This sort of commission should have been appointed prior to the establishment of the Goldstone Commission,The United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict and the fact that the Goldstone Report recommended the creation of such a commission is a poor reason for not doing so afterwards.

Military briefings cannot be a proper response to the grave charges leveled against Israel's government officials and military commanders. Military briefings are aimed at drawing lessons for the future. They are not suited to ascertaining the truth regarding war crimes. Not addressing these charges could be interpreted as acknowledging them, since they cannot be authoritatively refuted. This, in my view, was a historic mistake. Israel missed a golden opportunity to influence the development of international legal rules governing justifiable responses to threats emanating from terror-based nations and entities.

"You shall have one law" (Leviticus 24:22), or Beware of Double Standards

My second proposition is that rules and positions must be instituted uniformly and evenly. In other words, double standards—the application of different criteria to similar situations—are to be avoided. One clear weakness of the Goldstone Report is its failure to adhere to this principle. The commission was quick to ascribe the worst possible criminal motives to Israeli authorities. However, it evidenced overwhelming and inexplicable caution in attributing any nefarious motives to Hamas. The commission was cautious even when that group's actions clearly warranted such attribution, as, for example, when it employed civilians as "human shields" for its military operations. While the commission did not hesitate to give full weight to declarations by Israeli politicians during the course of the operation (even though these statements were probably a means of "letting off steam" at home or threatening Hamas, rather than an expression of policy), it refused to give any credence to the statement of a Palestinian minister affirming that the Hamas police were taking part in Hamas's combat activity.

We must always keep this principle in mind: Those who, like Israeli philosopher Asa Kasher and General Amos Yadlin, maintain that no additional risk should be imposed on our own soldiers in order to avoid harming the enemy's civilian population, must be ready to have the same standard applied by our enemies. Anyone who claims, for example, that a strike on an ammunition storehouse justifies the killing of 20 civilians (even though the other side has no trouble replenishing its arms supply) must be aware of the wider implications of this equation, such as the extent of justified collateral damage to Israeli civilians caused by an attack on the IDF headquarters. Those who determine that Palestinian civilians who attempt to protect military targets as human shields by creating a legal barrier to a possible attack thereby become "the enemy" and can be targeted as such (as the Israeli Supreme Court has ruled), come close to claiming that Israelis who purchase apartments adjacent to the IDF headquarters face a similar fate. Just to be clear: I am not referring to those who provide an actual cover for a military target by hiding it or otherwise preventing physical access to it, but rather to those whose actions make it legally difficult to justify attacking the target. In assessing the proportionality of the attack, account should be taken of the question whether the civilians likely to be injured are those who deliberately act as human shields. But to regard those who pose no danger to IDF forces as enemy targets is another matter. Similarly, some recommend broadening the conventional definition of "enemy" to include quasi-enemies—such as Hamas members who take no part in the movement's military operations but are active only in a religious, educational, or social welfare capacity as civilians, or people who simply support or sympathize with the movement. Before adopting this approach, one must recognize its implications. Following this path, and applying this logic symmetrically, leads to classifying as enemies Israeli reservists (even those who are not on active duty) and anyone permitted by the government to carry weapons. If the definition of enemies also includes potential enemies, the same logic applies to them. This rationale will serve the enemies of Israel to justify any attack on Israeli citizens who are not elderly. The prohibition against any attack on non-combatant civilians is not only a moral precept of the highest order, which is reason enough to abide by it; it is also essential from a pragmatic point of view. The struggle against terror is doomed to fail if the civilian population from which the terrorists emerge is itself defined as terrorist. Armed attacks on civilians serve the interests of terrorists because they result in the creation of additional terrorists.

If we take seriously, as we should, the obligation to ensure that in a war against armed terrorists, non-combatant civilians are not harmed, we must consider the question of how the Israeli public—including IDF soldiers—relates to the Palestinian population in general, particularly to the residents of Gaza. Given the current state of affairs, Israelis could come to view all residents of the Gaza Strip as enemies, mirroring the same tendency on the other side of the border. Unless deliberate educational, informational, and command-level steps are taken, these tendencies will develop even further. When the state, by law, denies compensation to a child living in the occupied territories who is injured as a result of an action performed by security forces—does it not turn this child, as well as other children, into enemies? When, again by law, the state prohibits a "mixed" Palestinian couple (an Israeli citizen and a resident of Gaza or the West Bank) from living in Israel, the message that comes across is that everyone from the other side is an enemy. The same message is conveyed by the imposition of a civilian blockade against all Gaza residents (alongside the military blockade which is justified for defense reasons). The benefit of this policy is highly doubtful, and its potential for breeding hatred against Israel is significant.

Israel's official position with regard to the International Criminal Court and the principle of universal jurisdiction also creates the uncomfortable sense of a double standard. There is a widely perceived mismatch between Israel's stance in the past (the very wide-scale incidence of Israeli penal law outside its borders; the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann, a milestone in the conceptual development of universal jurisdiction) and its current position regarding developments in international criminal law. The resulting impression is that Israel behaves one way when it perceives itself as a victim and another way when it believes it, or someone acting on its behalf, is a potential "victimizer." Israel is correct in demanding that universal jurisdiction must be closely monitored when applied by other countries. In other words, enforcement decisions must made by the highest criminal prosecution authority, as under Israeli law, where the authority rests with the attorney general. It is safe to assume that any reasonable chief prosecutor will refrain from involving his or her country in criminal proceedings against a government official of a country that is committed to the rule of law, that conducts thorough criminal investigations, and that ensures proper criminal proceedings for those charged with and later accused of crimes under international law. In this context, it is worth recalling the weakness of universal jurisdiction. Given the enormous backlog of criminal cases in most legal systems, a problem that countries are hard-pressed to solve, why would a country seek to apply its own criminal process to an act that has no link to the country where the suspect is located?

The attempt to limit universal jurisdiction to cases of genocide and crimes against humanity (of which Jewish people have been victims) is unconvincing, to my mind. The logic behind the appropriate application of universal jurisdiction in cases of serious crimes that violate fundamental human rights is that there is an inherent failure in the handling of these crimes in the countries of the perpetrators. The classic cases are crimes of this type committed on behalf of a country by its leaders, its security services, or its army. This scenario applies, for example, to war criminals and to state-sponsored torture (as in the case of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet). Claiming that the country itself should handle these types of crimes implies that they are not treated with the proper degree of seriousness. Obviously, there is an inherent and substantial flaw in the ability of a country to respond properly and genuinely to actions that are committed in its name and that, to some degree, are its own.

Universal jurisdiction clearly serves as a necessary means of whipping nations into doing what, in any case, they are obliged to do but tend to do only as a last resort. The Israeli experience proves that the presence of universal jurisdiction does, indeed, spur the military to abide by the precepts of international law. It is not at all certain that Israel's High Court of Justice would have ruled as it did on the use of West Bank Palestinian residents as human shields without being able to invoke international criminal law.

In particular, it is our ambivalence towards war crimes that should make us wary of applying double standards. When war crimes are committed against us, we are filled with anger and quick to express our moral indignation. When we ourselves are accused of war crimes attributed to our "good boys" in uniform, our reaction is far more complex and lacks the element of trenchant denunciation. It seems that the right response to war crimes committed against us must also be the right response to war crimes committed by us. More on that later.

Israel's reticence with regard to universal jurisdiction is especially puzzling given the wide acceptance of the principle in its own laws. In this context it is said: "Justice begins at home." Those who demand that others limit the scope of universal jurisdiction must abide by the same standard in their own backyard.

Given the inherent connection between the development of international criminal law and the horrors of the World War II, and especially the Holocaust, I deem it unfitting for Israel, as the Jewish State, to turn its back on or express hostility toward that law. It is true that international criminal law evidences serious weakness today. We would be hard-pressed to claim that it excels in mechanisms that ensure equal treatment for all. On the contrary, we must admit that its enforcement capabilities depend on the international power and status of the very countries from which the suspected criminals emerge. Nevertheless, in my opinion, a flawed international criminal law is better than no law at all.

Beware of the Blind Spots

My third proposition is to beware of blind spots—factors that do not enter into our moral equation despite their relevance. If we ignore a relevant consideration or piece of information, we are likely to reach the wrong conclusion. This principle is more difficult to apply since it requires greater effort to stretch our imagination to the greatest extent possible.

The major blind spot of the Goldstone Report is the nature of Hamas and the essence of Hamas rule in the Gaza Strip. As portrayed in the Report, Hamas is an organization of freedom fighters. There is no mention of it as a terror organization whose charter calls for the annihilation of the State of Israel, and no characterization of Gaza's rulers as a genocidal group of terrorists.

From a moral perspective, the principle of proportionality in connection with collateral damage—which dictates that harm to civilians must not be excessive when weighed against the gains of a military operation—requires the avoidance of injury to innocent persons unless there is no other choice. To reduce the danger posed by ignoring a blind spot, we must distinguish between three situations: 1) There is no concrete knowledge of civilians who are likely to be injured by an attack on a military target, but we can surmise, objectively, that this danger exists; 2) In the subjective assessment of a military commander, there is a real probability that civilians will be injured; and 3) There is concrete knowledge of certain, or close to certain, injury to civilians that will result. There can also be different probabilities regarding the chances of a military operation achieving its objectives. Relevant factors to be considered are if the gains to be made by the operation are viable or short-term, and the level of urgency of the operation—whether it must be immediate, or it can be postponed to a time when little or no injury will be caused to civilians.

Those who attempt to assess the functioning of Israel's civil society organizations (Arab/Palestinian and Jewish) with no appreciation of the fundamental moral injustice of a nearly two-generation military occupation and the denial of basic rights caused by it have done more than ignore a blind spot; they are guilty of complete moral blindness. Those who fail to see the moral corruption as an essential characteristic of the occupation, and the notion that Palestinians are both hostile and inferior that is instilled among Jews because of the occupation, are escaping reality in favor of their own, more comfortable virtual reality. It is only natural that the backdrop of discrimination against residents of the occupied territories, and the need to justify the denial of their rights, will lead to the emergence of an approach that robs these residents of their full humanity.

However unpleasant the task, we must remember that for many years, since 1967, Palestinians and human rights organizations have been claiming that Israel tortures terror suspects. Officially, and at all levels, Israel vehemently denied this charge. Years later, after the Bus 300 incident, General Security Service (now the Israel Security Agency, hereinafter "ISA") personnel admitted before the Landau Commission of Inquiry that they used physical and psychological pressure as a matter of course in interrogations and regularly denied the use of these methods in courts of law. We can only wonder whether the truth would have been revealed had the Bus 300 incident not occurred and whether we would still be living with the lie that the establishment, and consequently the public, adopted as the truth.

Even after the Landau Report, the ISA continued to use physical pressure in its interrogations. The practice persisted until, in response to a petition filed by human rights organizations, the High Court of Justice ruled that such methods were unlawful. Since the Court retained a narrow exemption to be used under exceptional circumstances, it is still unclear exactly what transpires behind closed doors in interrogations of suspected terrorists. The lessons we can draw from this matter are that not every charge of criminal activity cast against Israel and denied by Israel is false. Even if an official inquiry reveals no evidence to support the charges, there still may be some truth to them, given the difficulty of discovering the facts or the lack of motivation to do so. Human rights organizations, both Palestinian and Israeli, deserve praise for their efforts in this area. We must be wary of painting a comfortable, one-dimensional reality in which our side is all white and the Palestinian side is all black.

Similarly, we must avoid the tendency to justify every despicable act with a myriad of arguments when these acts were sanctioned by us or carried out in our name. The role of civil society organizations—particularly those outside the national consensus, with their own perceptions of reality and their own value systems-is a worthy and weighty one. There is no way to be certain that the majority's perception of reality is correct. Without the challenging of existing social conventions which can only emerge from individuals and organizations outside the establishment, there is no chance of revealing the truth, and an entire society can believe the lies fed to it by the government in power. The most important value in a democracy is the multiplicity of voices, perceptions, and opinions.

If Israel is dedicated to the value of protecting both its own civilian population and those of its enemies in time of war as a basic value of human civilization, it cannot restrict the steps taken by organizations to collect information on actions that appear to contradict this value. The position stating that war crimes are reprehensible acts for which all legal means—in Israel and abroad—must be taken to bring the perpetrators to justice is a moral and patriotic position. It is no less patriotic than the position stating that the country should not "air its dirty laundry" outside its borders. A law-abiding country that also adheres to international law can ignore neither the international dimension of these crimes nor the tendency of the establishment to refrain from handling them with the required degree of determination. Therefore, the use of coercive means to prevent the airing of such "dirty laundry" is out of the question, whether made through a smear campaign or by means of legislation aimed at preventing information from reaching outside sources. Such tactics are characteristic of totalitarian regimes. How would we respond if another country were to take legal action to prevent the collection or use of information that could play a role in criminal proceedings for war crimes committed against us? It is only natural that Palestinian victims would turn to these organizations rather than to official Israeli investigatory institutions, which do not even open avenues of access for these people. These organizations may be the sole address available to them. The Military Advocate General has more than once expressed appreciation for the contribution of these organizations in gathering evidence that might otherwise not be received.

It is important to stress, in this context, that military briefings are not meant as a tool for gathering evidence about war crimes. Their purpose is to provide information that can be used to improve military performance in the future. Under no circumstances can they be used as a substitute for criminal investigations when there is reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed. And we know, given the brotherhood of combat soldiers and the conspiracy of denial and silence it creates, that even vigorous criminal investigations can face roadblocks on the road to discovering the truth. We can only conclude that exceptional effort is required to expose war crimes. The harassment of organizations that contribute to the fact-finding effort is an additional obstacle on the road to truth-finding. It is a clear expression of hostility toward international law.

One argument made in the attack on civil society organizations in Israel is that they have great power, greater even than that of governments. Therefore, it is claimed, these organizations require the same degree of monitoring and control that is required for democratically elected governments. There is no greater distortion than this. The claim that these organizations are more powerful than governments, which can decree who will live and who will die, is totally groundless. The use of governmental mechanisms to supervise and control civil society organizations fits a totalitarian regime and serves a deathblow to Israeli democracy.

Another blind spot, one of momentous proportions and also well within the comfort zone of Israelis, is the position that the country faces monolithic hostility worldwide, which negates its legitimacy as the nation-state of the Jewish people, regardless of its actions or policies. Without a doubt, there is hostility toward Israel in the world that is unfounded and unrelated to the country's actions. Nevertheless, the perception of sweeping hostility is a case of blindness. Many people and countries around the world have friendly, or at least proper and fair attitudes towards Israel. For them, a decisive factor in these relations is the manner in which Israel conducts its affairs. And those who judge Israel's conduct are interested in two crucial issues: the country's continued control over occupied land and people, and its true willingness to establish peaceful relations with its neighbors. In the near future Israel will also be judged by its treatment of the Arab-Palestinian population within the state of Israel.

Israel's blind policy not only closes off any chance of tempering hostility against the country. It also undermines Israel's standing in the world, even among its friends. This reading of the situation is based on an important moral premise: We are not entitled to evade responsibility for our actions; nor can we expect others to relieve us of it.

"Moderate in judgment" (Pirkei Avot)

The final principle, which I will discuss briefly, is that of moderation or restraint. When standards are set for the actions of individuals or nations, they should not be so high as to be unattainable. I do not claim that the standards must mirror the current reality, and I would also caution against placing them too low. However, investigatory bodies, particularly those that are internationally sanctioned, may be tempted to set demands that are unreasonable.

The Goldstone Commission clearly yielded to this temptation in criticizing Israel for bombing and damaging the Hamas parliament building in Gaza—at night, when it was unoccupied. If even the empty institutional structures of a terrorist regime are not legitimate targets for attack, how are law-abiding nations supposed to defend themselves against terrorist states? If the place where blueprints for terrorist acts are drawn up is granted immunity because the site doubles as a parliamentary institution, then terrorist organizations would be well served to take control of civilian territory as a base for building a terrorist state. That is an obviously unreasonable standard. It appears that those who apply it fail to understand that the psychological dimension is critical in fighting a war against a terrorist organization. Moreover, the Goldstone Report in general ties the hands of a state under attack and thus eliminates its effective self defense.

To rob a law-abiding country of its ability to defend itself effectively is to grant a terrorist state the power to defeat that country. The question of what a law-abiding country is permitted to do against a terrorist state or a terror-supporting state (such as Lebanon), is critical to Israel's existence and security. In a press interview following publication of his report, Judge Goldstone gave an indication of his view on this question. When asked how Israel should have responded the attacks of Hamas on its citizens, he suggested that it should have deployed commando units to enter Gaza.

However, this strategy would almost certainly have resulted in a large number of Israeli casualties, put its soldiers at great risk of abduction (granting Hamas a victory), seriously endangered Gaza's civilian population in the event of military complications, and most definitely would have failed to stop the rocket fire on its towns and villages. In other words, following Judge Goldstone's reasoning, the fate of a defending state is doom.

The decision of the Israeli government to refrain from establishing a commission of inquiry deprived Israel of a golden opportunity to contribute to the development of international law in a way that will offer a state under attack a legally effective power of self defense.

It is unfortunate that individual interests, aimed at avoiding the possibility of personal accountability, outweighed this supreme national interest.

Prof. Mordechai Kremnitzer is Vice President of Research at the Israel Democracy Institute and Professor Emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. This article is based on a presentation that he made at the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists' London conference on July 1, 2010.

This article was originally published in Issue 48 of JUSTICE Magazine, the journal of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists. It has been reprinted with permission.