Out of Flight Mode

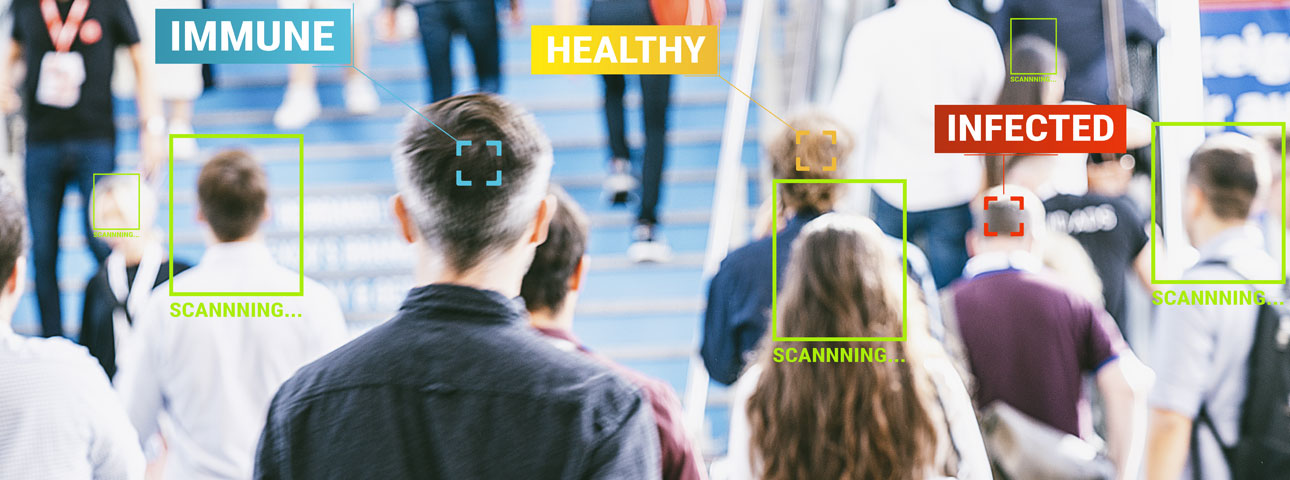

The Supreme Court ruled to limit contact tracing but is it really possible to put an end to the ISA’s bulk coronavirus surveillance?

Shutterstock

“We've got monsters.” That’s how the outgoing head of the Information Technology unit of the Israel Security Agency (ISA, also Known as Shin Bet or Shabak), Sasson (Sassi) Elia characterized the organization’s technological capacity. One of the ISA’s longtime monsters is “the Tool,” the database that to which telecommunication licensees (the cellular, internet, and landline service provider) feed a wide variety of communications metadata about the traffic passing through them. The Tool includes not only the metadata that the Israel Police can obtain by means of a court order (location, identity, and traffic), but also metadata in a broader sense—that is, everything except the actual communications content, as defined by the Wiretap Law. For the last two decades the Tool has been siphoning metadata about each and every Israeli citizen.

Nearly a year after the ministry of health began utilizing the ISA’s surveillance measures for COVID-19 location tracking, it has been ruled by the Supreme Court that the ISA will curtail its coronavirus cellular location tracking activities and limit them to cases of a refusal or inability to cooperate with epidemiological investigations.

Is it really possible to put an end to the ISA’s bulk coronavirus surveillance and focus on a limited number of specific cases, as the ruling stipulates? The truth is a simple “no.” Public discourse regarding ISA location tracking of confirmed coronavirus carriers and those with whom they have been in close contact, has at times created the impression that the ISA’s collection capabilities were being employed especially towards this end. In fact, the Tool will continue to track each and every one of us; the only difference is that ISA’s authority to run queries on its data from it in order to facilitate epidemiological investigations will be curtailed (and eventually eliminated, as the law authorizing coronavirus surveillance is set to expire by early July ).

In media interviews senior ISA officials regarded the database as “an endless collection of points in cyberspace, which don’t mean anything as long as no one accesses them.” In their view, as long as the data have not been scanned by a human eye, their mere collection poses no threat to human rights. However, what is certain is that the coronavirus pandemic has taught us that Israel’s automatic decision to rely on the ISA to deal with a civilian crisis has had a chilling effect. The low number of downloads of the Magen 2.0 contact tracing application and marginal events —such as young people who have purchased unidentifiable ‘dumb’ cellphones—are an indication that the ongoing tracking of people’s movements had had an effect in the real world.

The dozens of hearings on this issue held by the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee did not revolve around the question of whether the ISA should be permitted to partake in bulk surveillance of the country’s residents, but only around the information transfer interface between the ISA to the Ministry of Health. Along the way, substantial questions were obscured. For example, whether there is a real necessity need for the ISA to retain the history of Israelis’ phone calls and movements; and what safeguards are in place to ensure that the data is not misused or accessed without proper authorization.

The ISA’s internal controls of the Tool, and the service’s willingness to limit itself voluntarily, are not enough. Despite the many sessions of the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, the effectiveness of parliamentary oversight has been shown to be problematic. Also, in the bottom line, the Committee dragged its feet and proved unable to promote an alternative civilian measure to the ISA coronavirus location tracking.

The last few months have demonstrated that given the existence of this treasure trove of data, it was only a matter of time until other agencies would ask to make use of it. In the past, the ISA turned down a number of such requests, but occasionally allowed the police access to its data. Recent reports about an internet monitoring system operated by the Israel Police indicate that other organizations are eager to obtain similar data-collection capacity, and demonstrate how important it is to keep an eye on them. A public and much more transparent debate regarding intelligence and law-enforcement agencies online surveillance measures is necessary, as well as regarding appropriate legislation (rather than mere classified rules) which will regulate their use and oversight. For example, in a recently published study, I proposed the establishment of an independent oversight body, similar to the British model; in his book, Eli Bahar, the former legal advisor to the ISA, proposed removing the Tool from the ISA and placing it in the hands of a separate organization (similar to the situation in the Netherlands), along with changes in access policies and a narrower purposive scope of the database.

Within two weeks the ISA will narrow the scope of its assistance to the epidemiological investigations—and that would be a good thing. However, the Tool and the other “monsters” in the service of the ISA are still with us. Until their use is regulated by detailed and transparent legislation and placed under effective oversight, the public might rather keep its cellphones in flight mode.

The article was published in the Times of Israel.