25 Events that Impacted Israeli Democracy

In honor of the 25th anniversary of the Israel Democracy Institute, we feature a list of the 25 formative events that shaped Israeli democracy.

On Israel's 68th Independence Day and in honor of the 25th anniversary of the Israel Democracy Institute, we launch a list of 25 formative events that shaped Israeli democracy.

Some of these events are historical, others constitutional and legal. While our shortlist includes many landmarks in the evolution of Israeli democracy, we recognize that there are others. We invite you to share your ideas with us, too. If you have suggestions, email [email protected].

Come explore seven decades of Israeli democracy with us.

The Declaration of Independence

On Friday, May 14, 1948, the members of the Moetzet ha-Am, or People’s Council, held a formal meeting in Tel Aviv in which the establishment of the State of Israel was declared. The Declaration of Independence is the fundamental document of the State of Israel and its moral, national-cultural and democratic “lighthouse.” The Declaration of Independence set forth to the world and the country’s citizens the raison d'etre for the State of Israel as the setting in which the Jewish people would fulfill their right to self-determination. At the same time, the document expresses the state’s democratic character by stating principles regarding equality and justice for all its citizens. Many people, particularly during periods of polarization, division, and crumbling social solidarity, see the declaration as the basic “glue” that holds Israeli society together and as a document that provides Israel’s citizens with a broad common denominator.

The Altalena Incident and the Dissolution of the Palmach

One of the major challenges in the state’s early days was to merge the various Jewish underground movements, which had operated during the British Mandate into a single national army, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). This complex challenge reached its peak in June 1948 with the Altalena incident, during which a violent clash took place between the newly formed IDF and Irgun combat troops. Three IDF troops and 16 Irgun fighters died in the incident. That same year, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion also ordered the dissolution of the Palmach and the merging of its brigades into the IDF. During the process of dissolving the underground movements, the prime minister came under severe political criticism for using excessive force and acting out of political motivation. Despite this, many people felt these measures were vital for establishing the sovereignty of the young state.

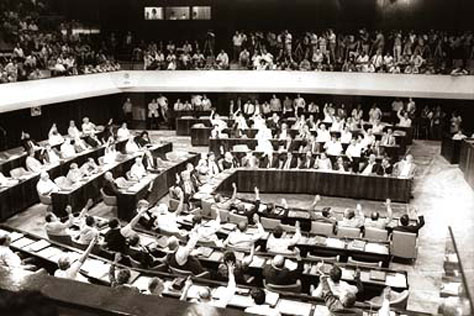

The Constitution that Was Never Written, and the Harari Decision

Even after 68 years, the State of Israel still lacks a formal constitution. The roots of this situation go back to two important decisions that were made in the state’s early days. The first was the Transition Law of February 1949, which turned the Constituent Assembly, which had been elected a month previously in order to establish a constitution, into Israel’s first Knesset. The second was the Harari Decision of June 1950, which established that Israel’s constitution would be made up of chapters, each of which would constitute a separate Basic Law. Once all the Basic Laws had been completed, they would be combined into a complete and formal constitution. This task has never been completed. Since the State of Israel has no constitution with a supreme and unquestioned status, some see it as a lacking – or "limping" – democracy.

The Reparations Agreement with West Germany: When Stones Were Thrown at the Knesset Building

The Israeli government began secret talks in the early 1950s with West Germany regarding individual and general compensation for the slave labor, property theft and suffering of Jews during the Holocaust. An immense public uproar ensued when Israel’s talks with the West German government became public. An enormous demonstration against the Israeli government took place in Jerusalem in January 1952. At the end of the rally, during which Menachem Begin, the leader of the Herut party, gave a sharply-worded speech, the demonstrators marched toward the Knesset, some throwing stones at the building despite the large number of police officers surrounding it. Dozens of police officers were wounded, the building’s windows were shattered, and several Knesset members were injured as well.

The Kol Ha-Am High Court Ruling

This ruling by the High Court of Justice in 1953 tested, for the first time, the boundaries of free expression when they came into conflict with national security. The background was a controversial essay published in Kol Ha-Am, the daily paper of the Israeli Communist Party (Maki), which was sharply critical of the government. Interior Minister Yisrael Rokach, using his authority under the Journalism Law, ordered the newspaper shut down for 10 days. The newspaper petitioned the High Court of Justice, which ruled in its favor. The ruling, which became a milestone and formative event in Israeli constitutional law, laid out the manner in which civil rights and freedom of expression could be protected when they clashed with other values.

The Kafr Qasim Massacre

The Kafr Qasim Massacre, in which 43 Arab civilians were killed by Border Police troops, took place in October 1956, on the eve of the Sinai Campaign. The Israeli army imposed a curfew on area residents due to security tensions, and soldiers were ordered to shoot at anyone breaking the curfew. Several dozen inhabitants of Kafr Qasim had been working in the fields that day and did not know that the curfew had been moved to an earlier hour. When they returned from their work, they were shot to death for breaking the curfew. Several days later, an investigative committee was appointed to probe the incident. It recommended that the families of the men who had been killed be given compensation and that those involved be prosecuted. The military court ruled that soldiers had a duty to disobey any order over which manifest illegality "waved like a black flag.”

Who Is a Jew: Ben-Gurion’s Letter to 50 Jewish Sages

The issue of "who is a Jew" is one of the basic controversies that has accompanied the State of Israel from the day it was established. The original form of the Law of Return contained no definition of "Jew." In 1958, a coalition crisis erupted over the interior minister’s explicit order to ministry clerks to register as Jewish anyone who, in good faith, declared him or herself to be so. The ministers from the National Religious Party resigned from the government, and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, searching for a compromise, sent a letter to approximately 50 “sages of Israel” asking their opinions on the issue. Since most of the respondents supported a definition according to Jewish religious law, the rule was changed to register as Jewish only those who had been born to Jewish mothers and were not members of any other faith, or those who had undergone conversion. The Law of Return was also amended in this spirit approximately a decade later.

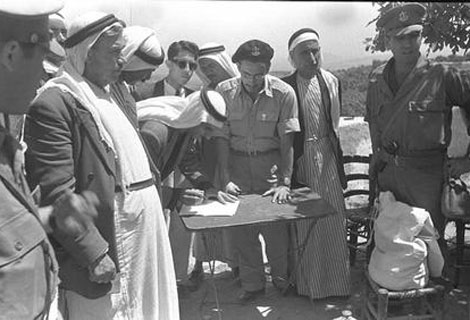

The Repeal of Martial Law

Between 1948 and 1966, Israel’s Arab citizens lived under martial law. During this period, many restrictions were imposed upon the Arab population that violated basic civil rights and subjected them to discrimination. For example, Arab citizens were required to present travel permits in order to leave their communities, and had to receive permits for some of the jobs in which they worked. Although demands that martial law be lifted were made in the Knesset as early as the mid-1950s, various proposals on the issue were rejected. It was only in 1966, almost two decades after martial law had been imposed, that Prime Minister Levi Eshkol stood at the Knesset rostrum to announce its repeal.

The Six Day War and the Settlement Enterprise

During the 1967 Six-Day War, the State of Israel conquered territory that tripled its size. Though Israel later ceded the vast majority of that territory in the context of a peace agreement with Egypt, the war changed the contours of Israeli politics and opened an ideological rift that has been at its core ever since. Today, advocates of "Greater Israel" see continued control of the territories in Judea and Samaria, and the strengthening of Jewish settlement there, as an expression of the Jewish people’s historical right to the Land of Israel and also as a vital security necessity. Those who favor withdrawal from Judea and Samaria believe territorial compromise is a prerequisite for peace and that perpetuation of the current situation, in which residents of the same area do not enjoy equal rights, casts a heavy cloud over Israel's democratic future.

The Black Panthers Protest Movement

The Black Panthers protest movement was established in 1971 by members of the second generation of Mizrahi immigrants who felt that the state discriminated against them because of their ethnic background. The Black Panthers protested this discrimination and demanded their socioeconomic status be made equal to that of Jews who came from Western countries. Their struggle won the support of academics and social workers. The Black Panthers organized several demonstrations that ended, on occasion, in clashes with police. A statement attributed to Prime Minister Golda Meir after meeting with representatives of the group — “They are not nice” — took root as a representing the ruling party’s cultural snobbery toward Mizrahi Jews. The movement disbanded in 1973 over internal disputes and was never elected to the Knesset. Several of its prominent members later joined other political parties.

The Agranat Commission’s Report

The Agranat Commission was appointed by the government shortly after the Yom Kippur War in 1973 to examine the decisions of military and political echelons that led to what became known as ha-mehdal (“the fiasco"). The commission decided that high levels of the military echelon bore personal responsibility for the fiasco because they had erred in judgement. It was recommended these individuals be dismissed. As far as the political echelon — Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan — the commission did not attribute any errors to them or assign them personal responsibility, even if it was hinted that they ought to bear the consequences by virtue of ministerial responsibility. The public uproar that followed the publication of the commission’s report led to Golda Meir’s resignation as prime minister, and Dayan was not appointed defense minister of the next government. Besides the recommendations for dismissal, the commission cited a lack of clear separation of powers among the cabinet, the defense minister, and the chief of staff, thus making a decisive contribution to standardizing the relationship between the political and military echelons.

The Elections Upset of 1977

After almost three decades of Mapai rule, the 1977 elections resulted for the first time in the Likud, led by Menachem Begin, becoming the ruling party. This was a significant test for Israeli democracy, and it may be said that Israeli democracy met it well. Despite the astonishment and shock among broad segments of the population, the voters’ will was respected and a transfer of power took place. The precedent of orderly transfers of power was very important from a democratic perspective.

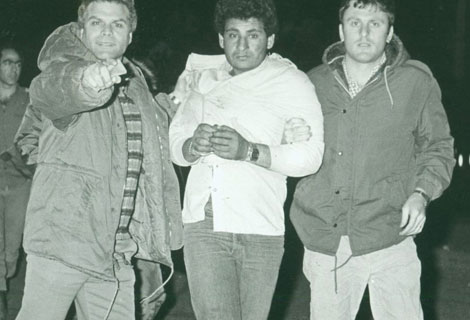

The Bus 300 Affair

This "affair" was a legal incident that took place following the hijacking of Bus 300 by four Palestinian terrorists in April 1984. Two of the terrorists were killed on the bus by Israeli troops during the fight to regain control of it, and two others were captured alive by Shin Bet personnel, but killed shortly thereafter. Two committees probing the circumstances of the captured terrorists’ deaths discovered evidence that the Shin Bet had engaged in a cover-up and in obstruction of the investigation of the incident. In a controversial act, four of the people involved in the incident received a presidential pardon even before they were put on trial. Seven other Shin Bet employees were pardoned later on. The Bus 300 affair revealed serious flaws in the Shin Bet’s integrity and actions, and gave rise to a demand for comprehensive self-criticism by that organization.

The runaway inflation of the mid-1980s compelled the unity government to take extraordinary measures as part of an economic stabilization plan. A bill was attached to the budget bill for 1986 that contained a large number of reforms, privatizations, and legislative amendments. This became known as the Arrangements Law. The use of a law to include a large number of measures was seen as justified at the time due to a sense of economic emergency. But once the Israeli economy had recovered and the governments were still using this extraordinary method — even adding reforms to it that had nothing to do with the state budget — criticism of it began to surface. Most of the complaints have been about the fact that the hasty legislative procedure does not allow for substantial discussion of the law’s various provisions, does not enable minimal transparency or fair public criticism, and therefore weakens the legislative branch’s supervision of the government.

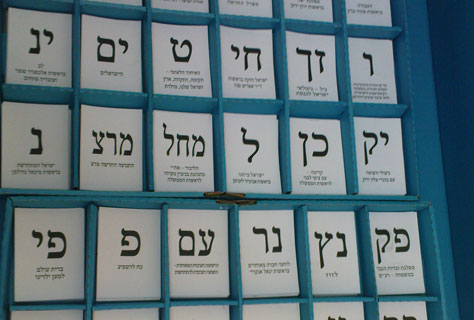

The Disqualification of Meir Kahane from Running in the Knesset Elections

The tension between the right to be elected and the need for democracy to protect itself against those who would subvert it found clear expression in the disqualification of parties from running for the Knesset. The Central Elections Committee disqualified the Kach party, led by Meir Kahane, from running in the elections on the grounds that the party was racist. However, the High Court of Justice overturned the decision due to lack of authority, and Kahane was elected to the Knesset. Kahane was disqualified again four years later, after the Knesset amended the law, and this time the High Court of Justice upheld the Central Election Committee’s decision. The law was further amended in 2002 in a way that permitted the disqualification of parties or candidates that supported armed struggle against Israel. Although several attempts have been made to disqualify Arab political parties and Knesset members on that ground, the High Court of Justice has stopped all of them so far.

The Basic Laws of 1992 and the “Constitutional Revolution”

The Knesset passed two Basic Laws in 1992 that, for the first time, dealt with human rights. Three years later, the High Court of Justice ruled, in the Mizrahi Bank case, that the status of the Basic Laws outranked the status of ordinary laws. Thus it was determined by virtue of interpretation that the court had the authority to rule regarding the constitutionality of the Knesset’s laws. This paved the way for the court’s judicial review of the Knesset’s laws in what became known as the “constitutional revolution,” which took the form of judicial activism of the court versus the other branches of government. This act is the focus of public controversy between those who claim that a strong court is vital to the strengthening of democracy and the protection of civil liberties, and those who believe the court took upon itself powers that do not belong to it and that it does not represent the spectrum of opinions in Israeli society.

The Direct Election of the Prime Minister

While many initiatives for political reform have been proposed, the vast majority of them were not approved. The Knesset approved the most significant reform in the structure of government in 1992, and it went into effect four years later. The system of direct election of the prime minister allowed citizens to vote using two ballots: one for the party and another for the candidate for prime minister. Despite the hope that the method would strengthen the prime minister and the large parties, the opposite occurred. The voters split their votes, the sectorial parties thrived and the Knesset reached unprecedentedly high levels of fragmentation. The direct-election system was abolished in 2001, and Israel went back to using one ballot in 2003.

The Opening of Channel 2 and Commercial Television

The establishment of a second television channel in Israel marked a transition from the period of the state’s monopoly over the broadcast media — radio and television — to a time of many more, and more commercial, broadcast media. Channel 2 quickly became Israeli society’s new element of tribal cohesiveness. On the one hand, it was a symbol of commercialism; Channel 2 was supported by advertising — sometimes including hidden advertising — which was subject to pressure and influence from shareholders and business partners. It also brought to Israel "shallow" content and reality shows. Finally it represented a drive for truth with its impressive journalistic ethos that succeeded in creating a news company of its own and top investigative programs such as "Uvda" (“Fact”), which served as an anchor of excellence even as public broadcasting in Israel was fading away.

The Rabin Assassination

The peace talks with the Palestinians, the Knesset’s approval of the Oslo Accords, and the suicide bombing attacks of 1994 and 1995 led to severe polarization between the right- and the left-wing parties in Israel. The political right charged that the government’s policy had led to the terror attacks and endangered the State of Israel, and led an aggressive public campaign claiming the government was not legitimate. During some of the protest actions and demonstrations, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was branded a traitor. The campaign of incitement against Rabin reached its peak in the autumn of 1995 after the signing of the Oslo II Accords. Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir on November 4, 1995 after a peace rally at Malchei Yisrael Square in Tel Aviv.

The Alice Miller Case

The High Court of Justice’s ruling on this case is considered one of the most important and precedent-setting rulings, due to the constitutional and ethical statements made regarding the prohibition against discriminating against women. Alice Miller, who was drafted to the Israeli army through the Academic Reserves program, asked to be allowed to enter the pilots’ course. Her request was denied on the grounds that according to standing orders, women were not to be integrated into combat professions. With assistance from the Association of Civil Rights in Israel and the Israel Women’s Network, Miller submitted a petition to the High Court of Justice, which ruled in her favor. The ruling opened various military positions to women.

The October 2000 Events and the Or Commission’s Report

Some of Israel’s Arab citizens joined their relatives’ violent protests in Judea and Samaria in early October 2000 following disappointment over the failure of the peace process and the visit of opposition leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount. In a space of approximately 10 days, violent demonstrations and incidents took place during which 12 Arab citizens were killed. The government appointed a panel of inquiry headed by Judge Theodor Or to investigate the events. The Or Commission’s report, which was released in 2003, stated that the violence in the Arab sector had broken out due to the Israeli government’s long-term discrimination and neglect of that sector. The commission also cited statements by the Arab leadership as a provoking factor, and recommended (among other things) narrowing the gaps between the Jewish and Arab sectors.

The Disengagement from Gaza

This political plan, which was put forward by Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, mandated the evacuation of the Israeli communities in the Gaza Strip and in northern Samaria, unilaterally and without negotiations with the Palestinian Authority. It was carried out in August and September 2005 after a tumultuous political battle. Although the public protest of the plan was accompanied by fears of civil war and disobedience by members of the religious-Zionist movement, the plan was carried out with no severe violent incidents. The implementation of the plan and the protest within the Likud resulted in the resignation of Sharon and a group of ministers and Knesset members from the Likud faction, and the establishment of the Kadima political party.

The Social-Justice Protest

The social-justice protest comprised a series of protest actions and demonstrations that took place in the summer of 2011. The protest, which began on Facebook pages, focused on the shortage of affordable housing in particular and the high cost of living in general, and resulted in the establishment of a tent city on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv, and others in other cities. The government’s response was to establish the Trajtenberg Committee, which examined and suggested solutions for the demonstrators’ economic demands, and principally for the high cost of living and the social inequalities in the State of Israel. Some see the protest as a turning point in the public’s mood: from a protracted period of apathy and escapism to strengthening the belief in ordinary citizens’ ability to effect change, have greater political participation and awareness, and demand elected officials adhere to democratic values of transparency and accountability.

Army Service and Ultra-Orthodox Society: An Exemption for 400 Yeshiva Students

The dispute over drafting ultra-Orthodox yeshiva students is among of the most enduring in Israel’s history. Many people regard the exemption that is given today to thousands of yeshiva students as severe discrimination and an essential violation of equality. The exemption originated in an order of the prime minister and the defense minister in the state’s early days to defer army service for yeshiva students, who numbered only 400 at the time. The late Prime Minister Ben-Gurion later, in 1958, expressed a degree of regret for having consented to the arrangement, and warned that the incidence of draft-dodging would become more widespread. The abolition of the annual quota of exemptions (by then Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1977) caused a sharp increase in the number of those receiving exemptions. Following a petition to the High Court of Justice, the Knesset established a public committee and passed the Tal Law. Since there was no substantial change in the drafting of yeshiva students, another arrangement, the Equal Burden Law, was passed in 2014. But it has not been implemented yet and there current plans to change or abolish it.

Equals Under the Law: A Former Prime Minister and President in Prison

The rule of law is a necessary feature of a liberal democracy, and one of its principal tests is its equal treatment of ordinary citizens, elected officials, and members of the elite. The current situation in which a former president and a former prime minister are serving prison sentences, can be interpreted as evidence of the strength of the institutions of the rule of law and the law-enforcement system’s equal and unbiased treatment of criminal suspects. On March 22, 2011, former President Moshe Katsav was sentenced to seven years in prison and two years probation for rape, indecent acts, sexual harassment and obstruction of justice. On February 15, 2016, former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert began a 19-month jail sentence for bribery.