Israel’s Rabbinate Should Welcome These Kashrut and Conversion Reforms

They do reduce the Rabbinate's centralized power, but in very different ways, which fundamentally upholds the rabbis' authority, rather than undermining it

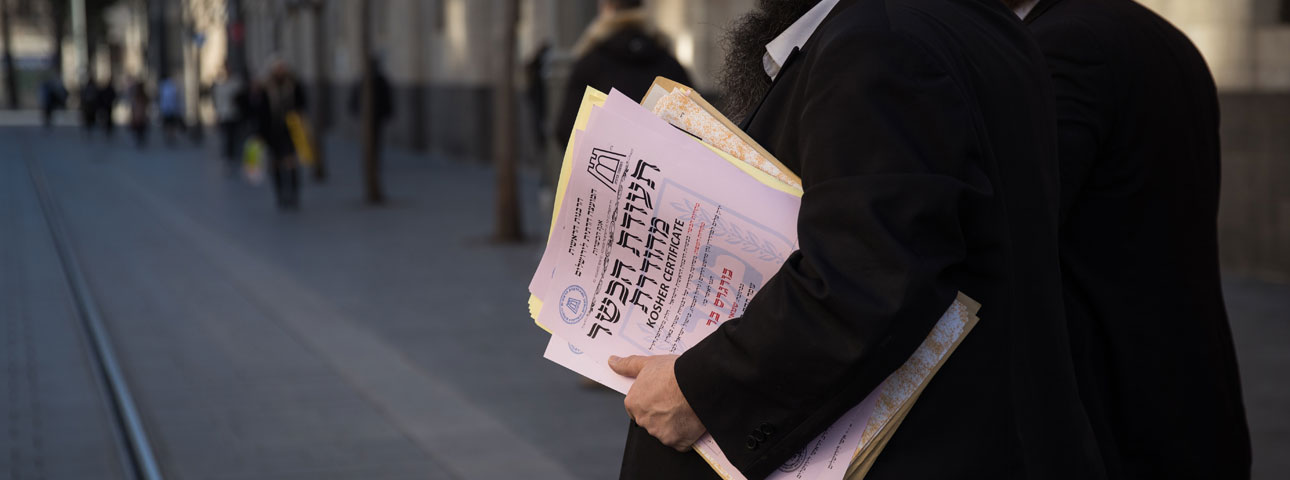

Flash 90

At the heart of the initiatives being led by Minister of Religious Services Matan Kahana are the planned reforms to kashrut and to conversion. According to the Kashrut reform, the Chief Rabbinate will no longer have the power to award kashrut certification directly, and will instead become a regulatory body overseeing public and private institutions that will be allowed to issue kashrut certificates. According to the planned conversion reform, city rabbis will also be given powers to perform conversions. Not surprisingly, these plans have aroused fierce opposition. Their opponents have put forward extreme arguments, couched in inflammatory language, protesting against the reforms and against Minister Kahana. But this stormy debate has overlooked a significant difference between the two planned reforms, which is critical for understanding their underlying justification. This article aims to clarify this distinction.

The ultra-Orthodox strongly oppose both reforms, which they view as a means for weakening the Chief Rabbinate and paving the way for the entry of Reform Judaism into the conversion and kashrut arenas. They are deploying the harshest possible rhetoric, referring to “the destruction of the Jewish state.”

To counter these concerns, Kahana argues that not only are the proposed reforms supported by a number of prominent religious-Zionist rabbis, but they also maintain the exclusive control held by Orthodox Judaism: The kashrut reform will place private kashrut providers under the halakhic regulation of the Chief Rabbinate, and the conversion reform will keep the familiar conversion tracks in the hands of city rabbis, who are without-a-doubt Orthodox.

By its very nature, public debate tends to ignore subtleties—in this case, the important difference between the two planned reforms. Furthermore, there are those who have a vested interested in lumping together the kashrut reform and the conversion reform, and presenting them as stages in a structured plan to destroy devout Judaism. However, closer investigation reveals that, despite what they have in common—devolving powers to other bodies outside the Chief Rabbinate—these plans are fundamentally different: The kashrut reform is based on the principle of privatization, while the conversion reform is based on the principle of decentralization. It is important to understand the significance of this distinction, as it goes a long way in responding to the claims of the critics.

As noted, the kashrut plan is about privatization. Currently, the Chief Rabbinate is the only body authorized to award kashrut certificates in Israel. While there is already a degree of decentralization in the current arrangement, in that local religious councils and city rabbis can also provide kashrut certification (under the aegis of the Rabbinate), these powers are not privatized. Private organizations, such as private religious courts (badatzim), cannot themselves issue kashrut certificates except as an addition to certification already granted by the Chief Rabbinate. According to the new plan, such private bodies will be able to award kashrut certification on their own, subject to Rabbinate regulation. Thus, the “kashrut market” will be opened to free competition between private organizations, a process that is expected to lead to diversification in the levels of stringency of kashrut that is provided, thereby giving expression to the various different halakhic and ethnic traditions, all within the boundaries of Orthodox halakha. A restaurant will be able to choose whether it wants kashrut certification from an Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox badatz, Mizrachi kashrut certification, kashrut certification from liberal religious-Zionist rabbis, or to operate without any kashrut certification.

By contrast, the rationale for the planned conversion reform is decentralization. It does not allow for the establishment of private conversion courts, but rather- distributes the centralized power of the Chief Rabbinate and allows city rabbis (who are also part of the state rabbinical establishment) to perform conversions for residents of their cities. This differentiates Minister Kahana’s plan from the initiative of the independent Giyur K’Halacha conversion court network, which is based on privatization. While the Giyur K’Halacha network seeks to privatize conversion and transfer it to private religious courts, Kahana’s reform keeps it in the hands of the State Rabbinate, while moving it out of centralized control into local rabbinates.

This is a welcome and critical distinction. It is based on the substantive difference between two arenas in the religion-state relationship in Israel: One-how to practice Jewish life in Israel, and the other- entrance gate into the Jewish people. In the first, the State of Israel is involved in shaping Jewish life in various fields, including the type of kashrut supervision enacted in restaurants and hotels, the management of cemeteries, and the design of mikvaot (ritual baths). In each of these areas, there are disagreements between different Jewish streams as to how to practice Jewish life—not just between religious and secular, or Reform and Orthodox, but even within the Orthodox halakhic world, where multiple different viewpoints exist. The kashrut laws of Sephardi communities are different from those of Ashkenazi communities; there are different approaches to the laws of shmita (the sabbatical year), Lubavitchers have different mikvaot from other groups, and so on. Here, it makes sense for the state to allow a diversity of customs and halakhic approaches to thrive, rather than enforcing a halakhic monopoly of the Chief Rabbinate. Just as no one would entertain the idea of the Chief Rabbinate running the markets that sell the “four species” for Sukkot, so should the other areas of Jewish life in Israel be left open to different traditions. Thus, privatizing the kashrut system does not constitute a capitulation to the wishes of secular Israelis, but rather- a recognition of the diversity of halakhic approaches. Even if every Israeli citizen were stringently halakhically observant, and even if the kashrut system operated by the Chief Rabbinate was flawless in its execution, there would be no justification for a single halakhic authority that enforces one specific type of kashrut.

The field of conversion is different, in that it is situated in a completely different arena, in which the rules for becoming a member of the Jewish people are dictated. Conversion not only influences the question of how Jews live their lives, but also defines the most basic question of “who is a Jew.” Here, privatization should not be an option, but decentralization is worthy of consideration.

From a historical perspective, halakha has always fully supported complete privatization of conversion. Every community religious court was empowered to conduct conversions to the best of its understanding. Neither was this the result of being scattered by exile; according to the halakhic tradition, even when the Sanhedrin (Assembly) operated in Jerusalem during Second Temple times, conversion powers were not held centrally but were given to every private religious court. At that time, a potential candidate for conversion who was turned away by Shammai, who represents the more stringent approach, could turn to Hillel who held a less stringent approach to conversion.

Despite this historical background, the privatization of conversion is a step that should be avoided in our times, while decentralization is a better option, for two main reasons.

The first refers to the Law of Return. Conversion automatically bestows the right to Israeli citizenship. Privatizing conversion would mean that any group of three individuals could effectively grant citizenship to anyone interested in immigrating to Israel. It is unthinkable that the State of Israel would hand over the keys to Israeli citizenship to private individuals. (A similar problem already exists regarding the recognition of conversions performed abroad, though at least in that case, this is conditional on conversion by a recognized Jewish community.)

The second reason relates to the continued ability of Jewish Israel to define itself as a Jewish society. While there has been fierce debate ever since the founding of the state over what public Jewish life should look like in the modern age, there has always been some degree of consensus on the question of who is a Jew. It should not be taken for granted that ultra-Orthodox residents of Meah She’arim and secular members of Kibbutz Beit Hashita agree that they belong to the same Jewish collective. Such agreement is, among other things, the result of the adoption of agreed rules for entry into the Jewish people—that is, the adoption of the minimum halakhic strictures that are agreed upon by all parties. Privatizing conversion would mean that every group can do as it likes and induct new members into the Jewish people. This in turn could lead, within several generations, to the disintegration of Israeli society into Jewish sub-societies that would not recognize the validity of each other’s form of Judaism.

Imagine an exclusive club of whisky afficionados. The club could withstand harsh disagreements over the relative merits of Scotch, Irish, bourbon, Japanese, and so on, and could even survive the formation of sub-groups who tend to drink separately from one another. But the club would not survive if every sub-group had the ability to admit new members independently. The same is true of Jewish society in Israel: It certainly can and should include diverse forms of Jewish life, from ultra-Orthodox to atheist, each with its own set of beliefs and practices. But it should strive for a consensus on the question of “who is a Jew,” lest the collective otherwise disintegrate into several groups with no connection between them.

In recent years, we are witnessing cracks in consensus in Israeli society about “who is a Jew.” This is mostly due to the large-scale immigration from the former Soviet Union, which included some who are not halakhically Jewish and whose descendants have become fully integrated into Israeli society, to the extent that they cannot be distinguished from their Jewish compatriots. While these young men and women are not considered by halakha to be Jewish, Israeli society as a whole struggles to see what makes them different from their fellow Israelis in school or in the IDF. The planned conversion reform is designed to narrow this gap by enabling city rabbis to help convert their city’s residents. To succeed, this form of conversion will have to be accepted by the majority of Israelis, which will only be possible if it is conducted by the state system (as proposed by the reform), and not by private conversion courts.

Thus, the reforms being led by Minister Kahana on kashrut and conversion are worthy of praise due to this significant difference between them. Privatization is the right strategy for kashrut, and decentralization- for conversion. This distinction will allow a welcome diversity in religious services, while also maintaining the necessary common denominator with regard to conversion and the defined boundaries of the Jewish people.

The article was published in the Times of Israel.