Israeli Collective Repentance

A collective Israeli repentance will enable us all to pray together for our common good, even if the content of our prayers is a matter of fierce disagreement.

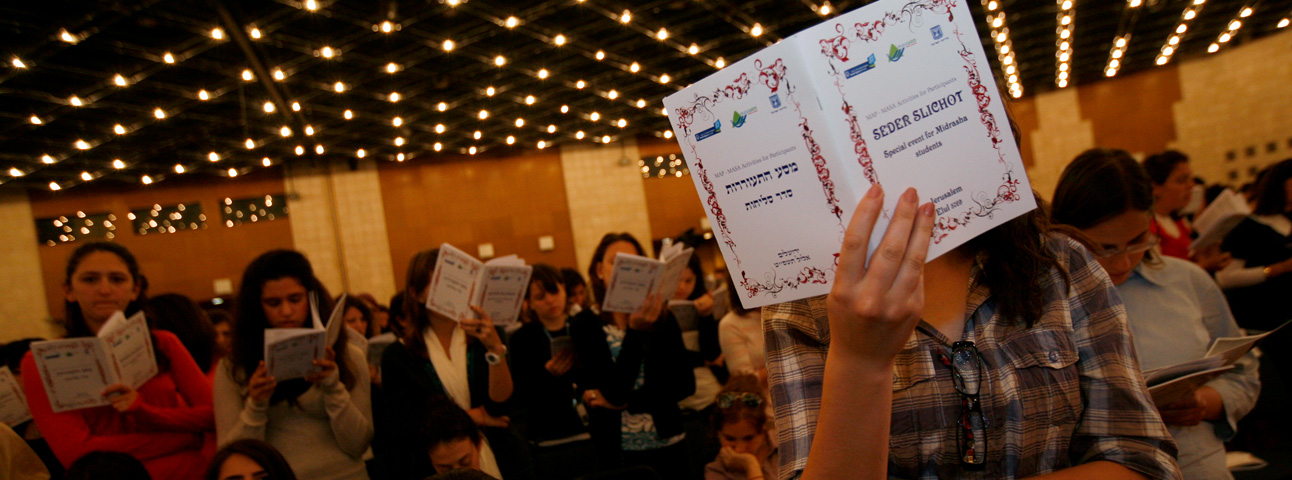

Illustration | Flash 90

During the High Holy Days we are called to conduct an intimate process of introspection and critical consideration of our deeds, with the aim of repairing whatever requires improvement—that is, to engage in repentance (teshuvah). We experience ten days of a pensive individual emotional process in which all of us are asked to take responsibility for our own lives and to ascend to the next rung on the moral ladder. However, alongside personal repentance, we should see repentance as a public challenge as well. The High Holy Days are also an opportunity for a collective Israeli self-reckoning aimed at repairing the situation we live in.

The Israeli public sphere has become an arena of heated conflict that pits rival visions against each other. Each vision seeks primacy in determining the character of the state and society. For example, consider the summers’ intense disagreements regarding the Jewish national identity of the State of Israel.

Secular Israelis see their national identity as the driving force of the State’s Jewishness. The ultra-Orthodox reject this completely and insist that religion is the only expression of our Jewishness; national identity by itself is an empty vessel. The National-Religious sector, as its name indicates, presents a third possibility that identifies both religion and nationality as components of a Jewish identity. And finally, the Arab sector would remove all manifestations of national identity from the Israeli public sphere, which is supposed to belong to all citizens, whatever their identity.

In light of this disagreement, the interpretation of what it means for Israel to be a “Jewish state,” as it is described in its Declaration of Independence and Basic Laws, is the subject of an intense dispute regarding both its very legitimacy (by the Arabs) and its content (among the various Jewish sectors).

These four visions are at odds regarding the Israeli ideal and the purpose of our shared existence. What the different groups have in common is an imperialist aspiration to mold the entire public space in their likeness. Thus our public life is played out as a zero-sum game, in which one side’s success is the other’s defeat. This cultural sword-whetting is unavoidable because we share a public space; painting it in one color or another influences all of us, for better or for worse.

This disagreement on its own is not a problem, it enriches our public life and adds value to the discourse. As our sages referred to it, it is a disagreement “l’Shem Shamayim” (for the sake of heaven). The problem is that in recent years our disagreements have been conducted in a way that has led us down a path towards mutual hatred. We Israelis tend to denigrate the other side through generalizations that delegitimize their stance. The left is portrayed as unpatriotic, post-Zionist, and Hellenizing. The right is portrayed as devoid of humanism, infected by xenophobia, and anti-democratic. The ultra-Orthodox are portrayed as parasites, extortionists, and misogynists. The National-Religious are portrayed as lawless, conspiring to impose religion on the public, and hungry for a hostile takeover of the institutions of government. And the Arabs? They are seen as evil plotters, disloyal, and a conspiratorial fifth column.

In Jewish tradition, the process of repentance has several stages: first, recognizing the sin and understanding the behavioral failure; next, taking responsibility and expressing remorse; and finally, making a resolution for the future and accepting a commitment to change one’s life in a way that will prevent a recurrence of said failing. Israeli society needs to embrace this journey as well.

First we, as a society, need to “recognize the sin,” which will be the basis for a collective Israeli repentance, and requires understanding and internalizing that the majority of each of these four groups does not fit the wicked stereotype attached to it in our discourse of hate. Second, we must recognize our failings as a society and express “remorse” by internalizing that each group that comprises the Israeli mosaic is rich and diverse and seeks only the best for us all.

And last, and most important, we must—“make a resolution for our future”. This step requires authentic leadership from each group to work out a strategy that creates a mindfulness of acceptance. Accepting the other groups for what they bring to the table and how they contribute to Israeli society, and embracing their visions. The great Israeli experiment, whose realization is crucial for the future of our national resilience, is to ensure that each of the Israeli identity groups continues to hold the vision that makes it special and fights for its acceptance, while also accepting the other identity groups—with their visions—as legitimate and as worthy partners in our joint future.

On Yom Kippur night, right before the chanting of the Kol Nidrei, the liturgy grants the congregation permission “to pray with the sinners.” In some ways, my visceral disagreement with the other groups’ visions may deem them “ sinners” in my eyes, but we must all pray together. A collective Israeli repentance will enable us all to pray together for our common good, even if the content of our prayers is a matter of fierce disagreement.

The article was published in the Atlanta Jewish Times.