The Return of Direct Elections for Prime Minister?

Prime Minister Netanyahu is promoting legislation that that will institute direct elections for prime minister. How would this proposal work? Will it resolve the political stalemate? Would the Supreme Court rule on its legality? IDI experts weigh in.

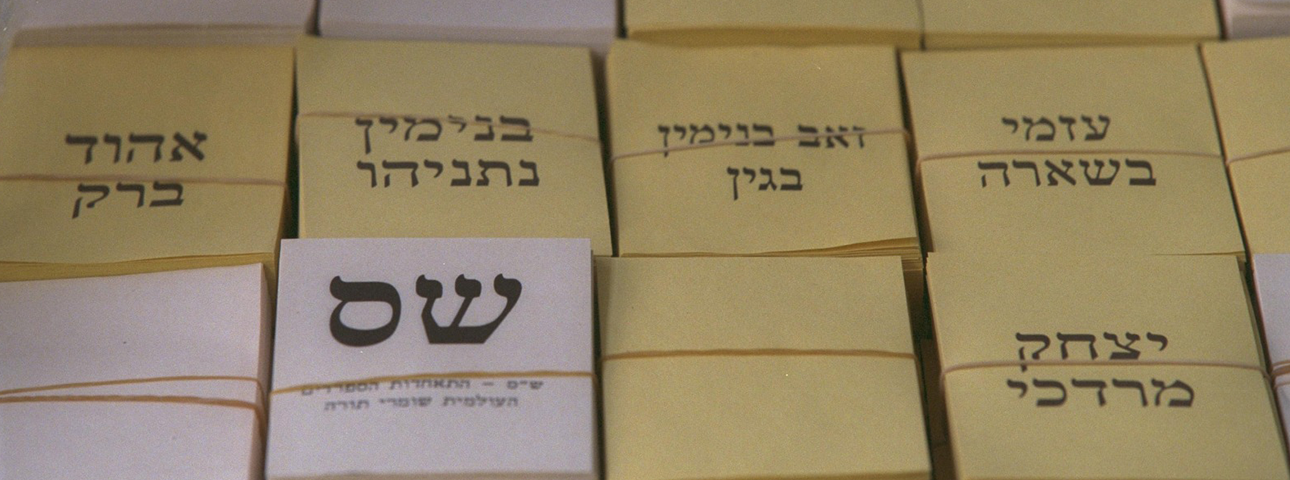

Credit: Ohayon Avi

What does the current proposal entail?

According to the current proposal, Israel will immediately hold additional direct elections, for the sole purpose of electing a prime minister. The winning candidate will begin to serve as prime minister straight away, and will also be handed the powers of the 'alternate prime minister,' marking the end of the 'parity' government formed last year. The new prime minister will have to put together a government that will be approved by the Knesset in a vote of confidence. Should the vote not pass, general elections for the Knesset will be held once more. Should the new government pass the vote, then (in a change to current legislation) it will not be permitted for another government to be formed during the current Knesset term. Thus, for example, if the Knesset were to pass a no-confidence vote, this would result in new Knesset elections, and not the formation of a new government.

What happened when direct prime ministerial elections were held previously in Israel?

Direct elections led to the disintegration of the party system, to unprecedented political fragmentation, and to greater reliance of the larger parties on the smaller parties. This was due to the fact that introducing an electoral system in which voters cast two ballots (one for prime minister, the other for a party) changed voter behavior. Many Israelis split their votes, casting one ballot for a prime minister from a large party to lead the country, and another ballot for a small party that precisely reflected their particular ideological or sectorial affiliation.

The impact on the large parties was dramatic. While the two largest lists won a total of 76 seats in the 1992 elections, by the 1999 elections (the second time direct elections were held) this had dropped to just 45 seats. Direct elections not only failed to correct the flaws in the political system; they actually made them worse. The new system made it difficult for the government to pursue and advance coherent policy, and the disproportionate power held by the smaller parties meant that the government operated under constant fear of early elections. These outcomes led to direct elections being quickly shelved in 2001, just five years after they were first introduced.

Direct elections also amplified the trend toward personality politics in Israel, and greatly weakened the institution of the political party. The bulk of the available resources were invested in promoting prime ministerial candidates, with most political broadcasts accentuating these candidates’ individual attributes and opinions, while the parties, political ideologies, and parliamentary competition were left by the wayside.

Is the electoral system becoming hostage to politicians?

From a political perspective, a two-ballot system is a terrible idea, because it weakens the major parties. While the current proposal put forward by Shas does not involve simultaneous elections for prime minister and the Knesset, it is still based on a separate ballot for prime minister, which will likely have an impact on voter behavior during the next Knesset elections as well. A situation in which the Knesset is elected via one method (one ballot) and the prime minister is elected by another method is unreasonable and illogical in a parliamentary system such as Israel’s. If the current distribution of seats in the Knesset is such that no member of parliament is able to form a government, then it is highly probable that even a directly elected prime minister would similarly be unable to do so.

Can the Supreme Court intervene?

There would appear to be grounds for intervention by the Supreme Court, based on the doctrine of a constitutional amendment that is itself unconstitutional. The current proposal would contravene the will of voters who voted for parties in Knesset elections, with the goal of these parties forming a government on the basis of the current coalitionary system. Instead, voters would find that the power of their vote has been diluted after the fact, via the introduction of an alternative electoral system.

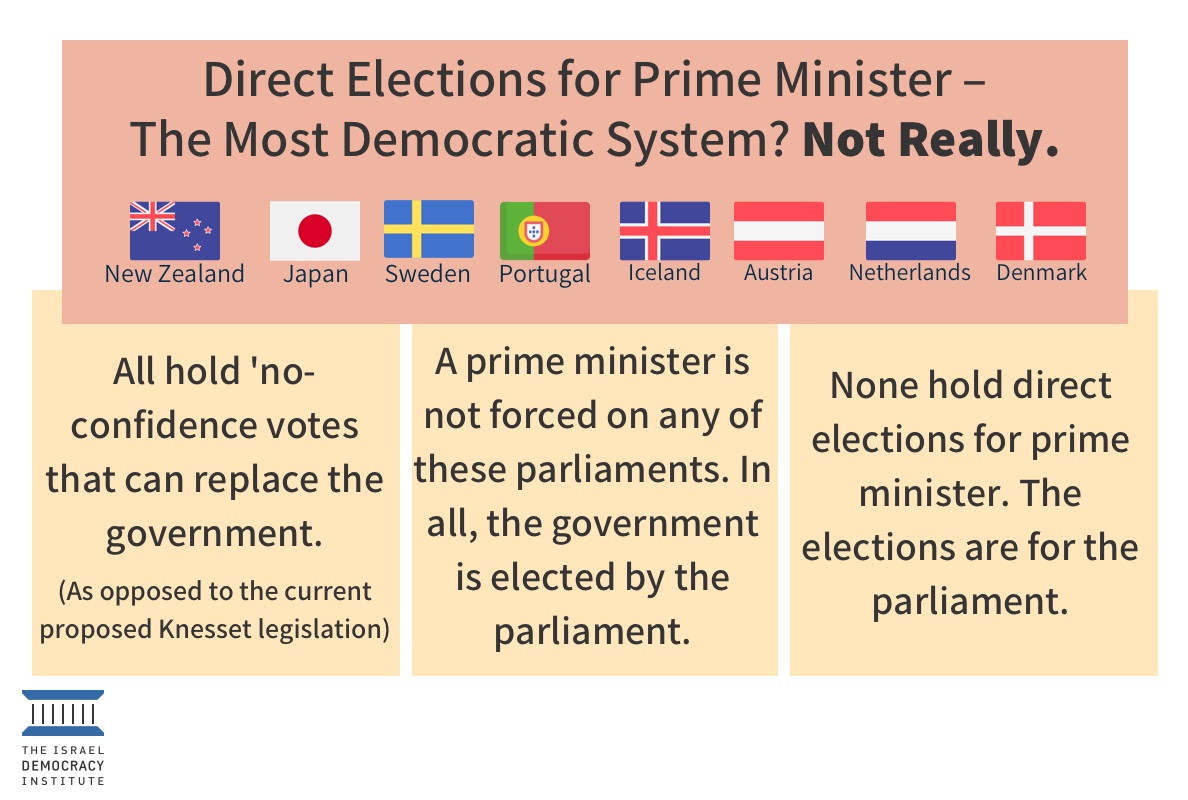

It should be noted that from a constitutional perspective, this proposal would mean further damage to Israel’s Basic Laws, its political system, and its citizens, all of which suffer from over-frequent and hasty amendments to legislation aimed at changing the rules of the political game even as it is being played. Democracies are founded on stable rules of the game. A change of this kind, immediately after elections, is a sign of a shift away from parliamentary democracy.