The Arab Vote in the Elections for the 24th Knesset (March 2021)

The recent elections proved, once again—especially against the backdrop of the Joint List’s meteoric success a year ago—the weakness of the parties’ base on the Arab street.

Turnout

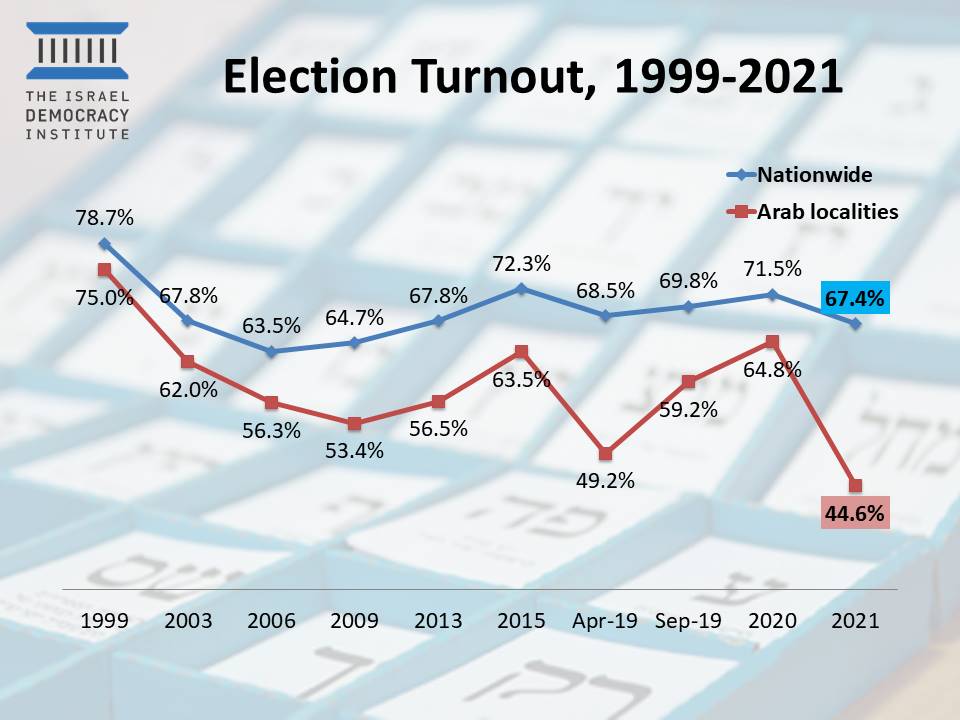

Anyone following the patterns of Arab citizens' participation in the Knesset elections over the last two decades notices that their turnout is significantly lower than in the past, and also considerably lower than the national turnout. The very participation of the Arabs in the Knesset elections has become a question for which the answer is not self-evident. The elections to the 24th Knesset (March 2021) brought this to light, this, when the percentage of votes in Arab localities dropped to an all-time low—only 44.6%—substantially less than the previous low point of 49.2%, recorded in April 2019.

The turnout percentage is computed on the basis of the total number of valid ballots cast by eligible voters; but the calculation for each locality does not include those who voted in double envelopes (absentee ballots). In general, the latter category comprises members of the armed forces, prison inmates, and civil servants, whose assignments prevent them from voting in their home district (such as Foreign Ministry staff).

This time, however, a significant percentage of these absentee ballots were cast by those in quarantine or confirmed cases of COVID-19, for whom special polling stations were set up. Their votes are not included in the calculation of the turnout percentage in their home localities, and are listed as a separate category in the overall figures.

We should remember that the percentage of both those suffering from the virus and those quarantined in the Arab sector is relatively high. According to Health Ministry data on the day before the elections, the percentage of confirmed cases in several Arab towns, including Nazareth in the Galilee, Umm al-Fahm in the Triangle, and Rahat in the Negev, was exceptionally high. In addition, in many Arab localities there were hundreds of persons in quarantine. This explains, for example, why turnout in the Triangle (especially its northern sector) was especially low: residents who voted in double envelopes at the special coronavirus polling stations are counted separately here. Hundreds of people were in quarantine in the area around Nazareth, the Sakhnin valley, and the northern lowlands (including large cities such as Shefaram and Tamra). So too in several large towns in the Triangle—Umm al-Fahm, Arara, Baqa al-Gharbiya, Taibe, Tira, and Kafr Qasim—with an exceptional percentage of eligible voters in quarantine. This was also the case in large localities in the Negev, including Rahat, Laqiya, Hura, Kseifa, and Tel Sheva, and the Bedouin settlements in the al-Qassum regional council.

In the elections for the 23rd Knesset, in March 2020, when Arab turnout was the highest in the last two decades (64.8%), the Joint List gained 18,077 votes in double envelopes, comprising 5.5% of all double-envelope ballots. This March, the two Arab parties—the Joint List and the United Arab List (UAL) which split from the Joint List—together received almost the same number of double-envelope votes—17,756, or 4.2% of the total of such votes. The fact that the decline in these numbers from 2020 to 2021 was much smaller than that in the total Arab turnout for the two elections indicates that many voters in Arab localities were ill or in quarantine and had to take recourse to voting by double envelopes. From this we learn, that the turnout recorded for Arab localities is less than the true figure. In any case, the turnout is abysmally low: at least half of all eligible Arab voters did not go to the polls in either year.

The elections for the 24th Knesset are somewhat reminiscent of those for the 21st Knesset, two years ago. In both cases the Joint List splintered in two; in both cases the two Arab lists won a total of 10 seats in the Knesset, and in both cases half of the eligible Arab voters stayed home on Election Day. There are diverse reasons for not voting. Some boycotted Knesset elections on ideological grounds, and others simply displayed political apathy to a fourth round of elections in less than two years. But it seems that most non-voters abstained in protest of the way the two Arab lists conducted themselves in the election campaign.

Unlike the April 2019 elections, this time around, the Arab public accepted the split in the Joint List and the resignation of Ra’am (UAL) with a modicum of understanding, due to the inability of the four components of the Joint List to adopt a uniform political discourse; for example on whether or not to cooperate with Benjamin Netanyahu or on a sensitive social issue such as the question of LGBTQ rights in Arab society.

The back-and forth clashes left a residue of bad feelings among the potential electorate and Ra’am coped better than the Joint List with the political crisis plaguing the Arab street. It was able to mobilize its support base, composed mainly of Islamic Movement activists and supporters (Negev Bedouins and succeeded in garnering the minimum required votes. This sent out a message which was in stark contrast to Netanyahu's campaign to encourage Arab citizens to participate in elections (even if through a vote for the Likud and not for the Arab parties) and exacerbated political frustration on the Arab street. Taken together, these developments resulted in an unprecedented low in Arab participation in the Knesset elections.

The Results in Arab Localities

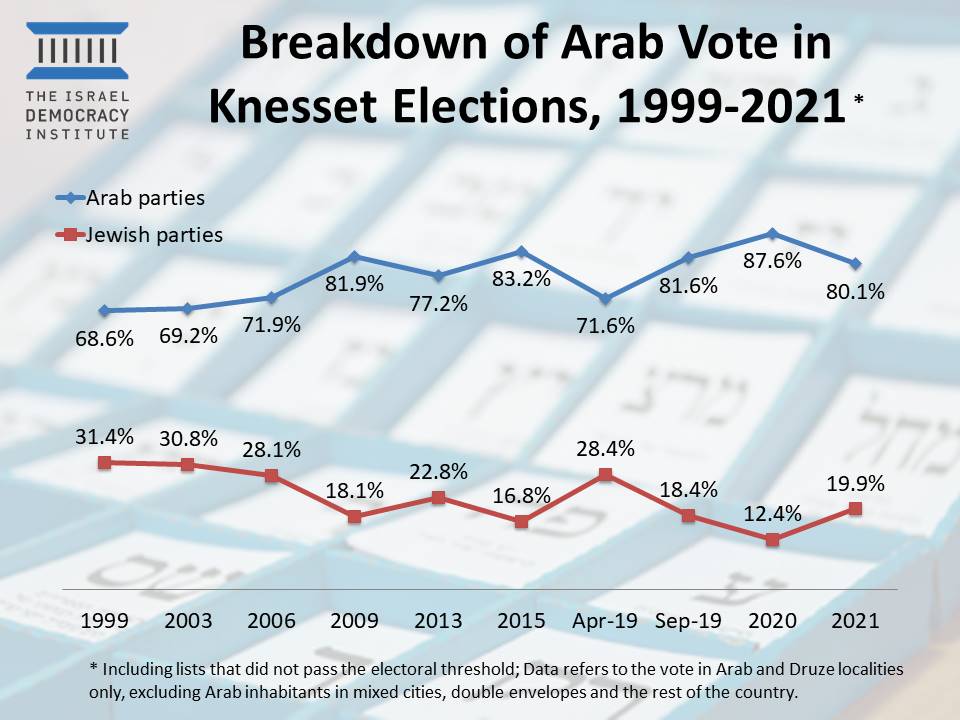

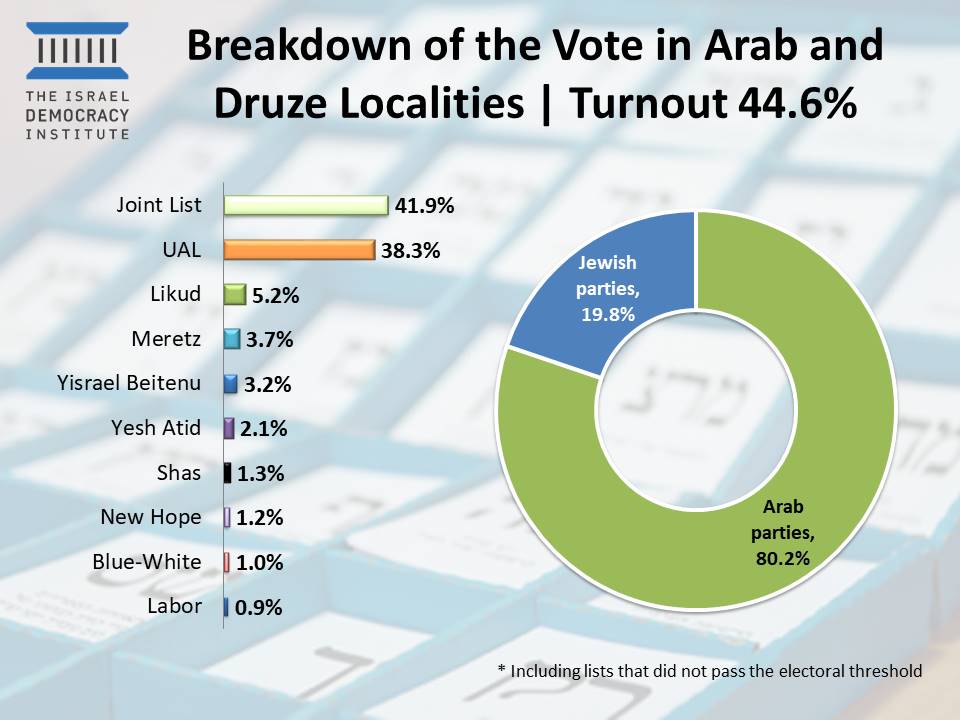

A solid majority of the Arab vote (80.2%) went to the two Arab parties. As a result, and despite the low turnout, both the Joint List and the United Arab List passed the election threshold and won Knesset seats. The rest of the Arab vote was divided among Jewish parties—mainly the Likud (5.2%), Meretz (3.7%), and Yisrael Beitenu (3.2%). This 80-20 breakdown of the vote in Arab localities is more or less the same as that recorded in all elections of the past decade.

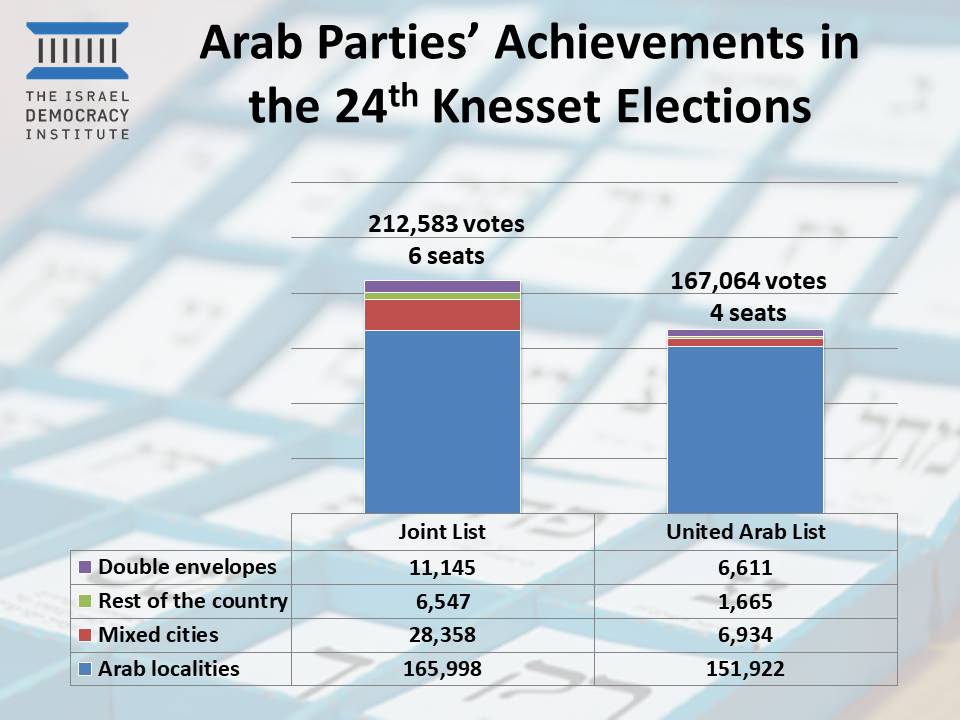

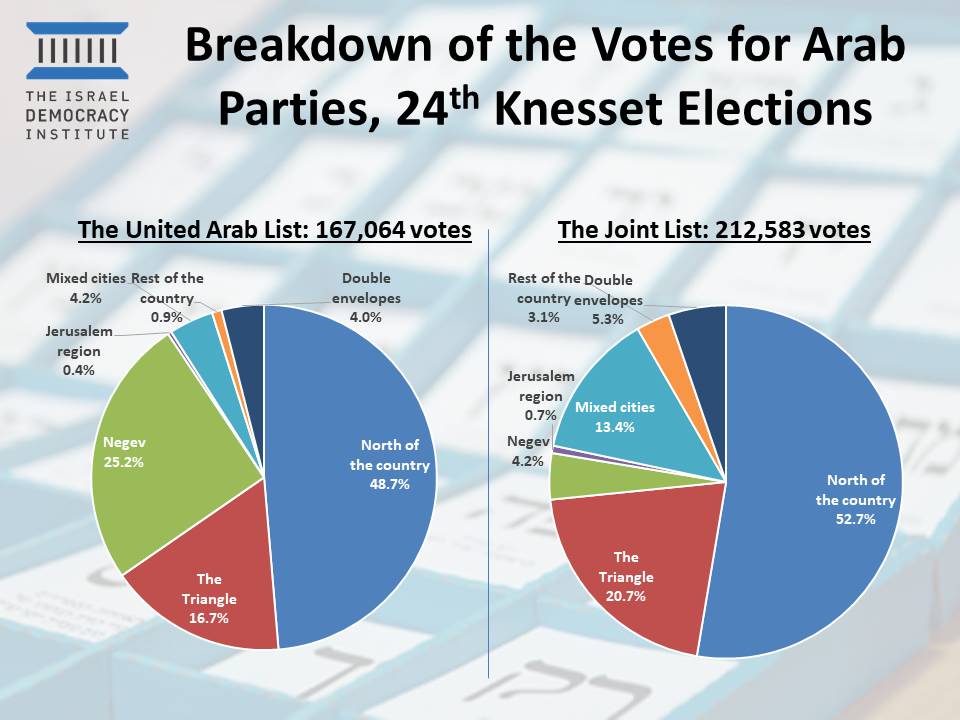

Of all political forces competing for the Arab vote, the Joint List remained the leading political force in the Arab sector, but we should note that in Arab localities, its advantage over the UAL was not significant (only about one-third of a Knesset seat). Where it did outpoll its rival was in the mixed cities (cities with both Jewish and Arab residents) and in predominantly Jewish localities elsewhere in the country where the Joint List received about 30,000 more votes than the UAL.

The Joint List, which comprised three parties this time—Hadash (Democratic Front for Peace and Equality), Ta’al (Arab Movement for Change), and Balad (National Democratic Alliance) (the new “Ma’an – Together” party dropped out a week before Election Day and threw its support to the Joint List)—won six Knesset seats: three for Hadash, two for Ta’al, and one for Balad. The UAL passed way over the threshold and won four seats.

Thus, of the four components of the Joint List as it competed in 2020, only the UAL maintained its strength, with four Knesset members. Hadash and Balad lost two seats each, and Ta’al one. For Hadash, this is the most disappointing performance since the 17th Knesset (2006); for Balad, it is the worst result since it began running in Knesset elections back in the 1990s. The latter could draw slight consolation from the fact that one of its stalwarts, Mazen Ghanaim, made it into the Knesset, representing the UAL.

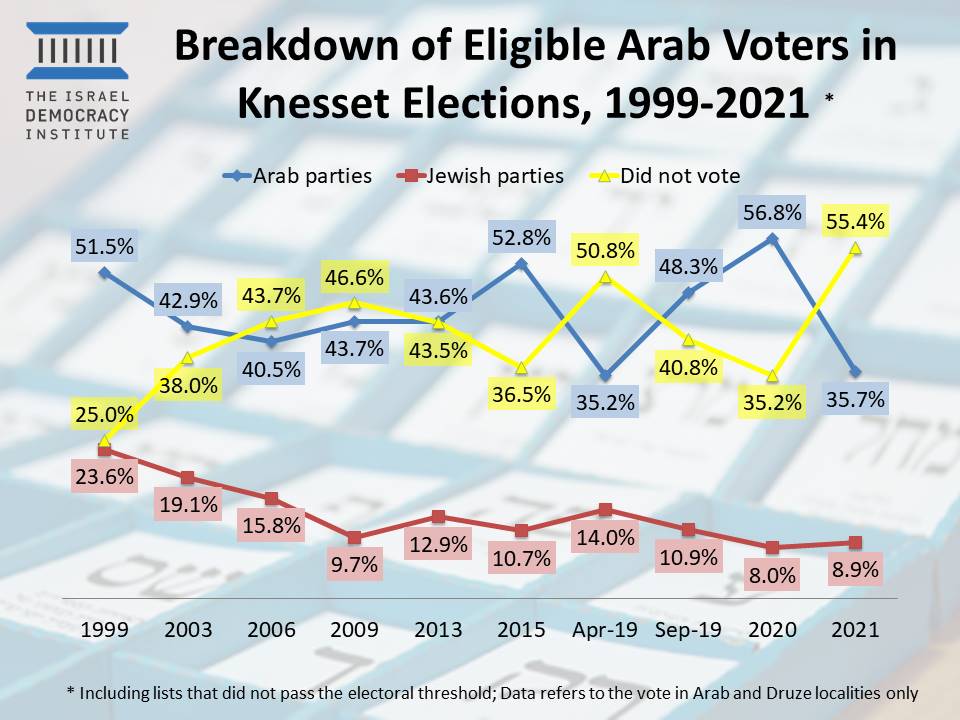

However, the above data reveals only part of the picture. In order to better understand political trends in Arab society, one must examine the behavior of all eligible voters in Arab localities vote over the years. This reveals the fact that for almost two decades the real battle for the voice of Arab voters has been going on between the Arab parties on the one hand, and the "non-voters party" (that is, those who do not participate in the elections,) on the other. The rise in the percentage of non-voters during this period is closely linked to the first organized elections boycott in the 2003 elections. This does not mean that the extent of boycotts based on ideology in Arab society is so large, but rather—that in some circumstances, the slogans of boycott and abstention fall on a larger number of attentive ears in the Arab public and encourage them not to participate in elections. In the first decade of the current century, it was the powerful imprint left by the events of October 2000 on the Arab public and the rise in distrust of the State and its institutions that led many Arab citizens to turn their backs on the ballot box. In recent years, on the other hand, abstention from voting is directly related to the conduct of the Arab parties and is influenced by the political tensions and rivalries among them. Thus, in recent years, the Arab parties have had the upper hand only in election campaigns in which they ran as part of the Joint List (2015, September 2019, 2020), and in which they received the support of about half of the eligible voters in Arab society. In all other cases, the “non-voters’ party” gained 50% or more of the eligible Arab voters.

The sharp fluctuations in voting rates in recent years demonstrate the growing incapacity of the Arab parties' ability to attract a loyal support base which would give them their vote under any and all circumstances. They also demonstrate that the numbers of loyal supporters of the parties have shrunk to only a third of those eligible to vote in Arab society. The final political decision is therefore in the hands of the Arab voter: if satisfied with the conduct of the parties, he or she will go to the polls; if not—will abstain. On the other hand, the decline of Arab support of Jewish parties is notable. In the last decade, the average rate of support for them on the Arab street is a little over 10% - about half the average rate two decades ago.

Northern Israel

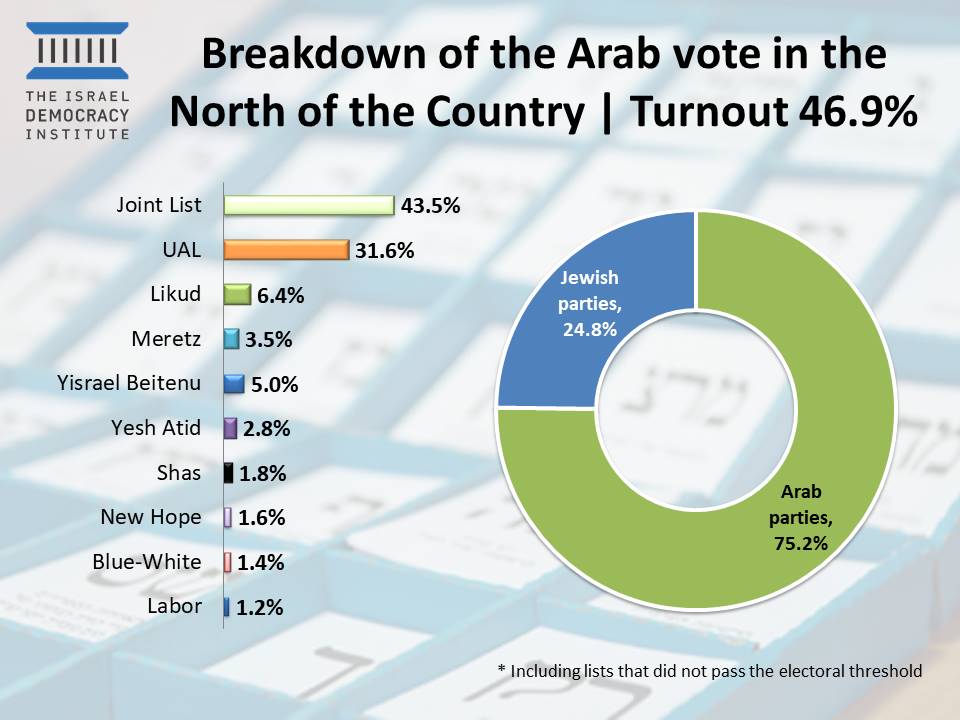

A clear majority (75.1%) of Arab voters in northern Israel—the Galilee, the northern valleys, and the Carmel Coast—cast their ballots for the two Arab lists: 43.5% for the Joint List and 31.6% for the UAL.

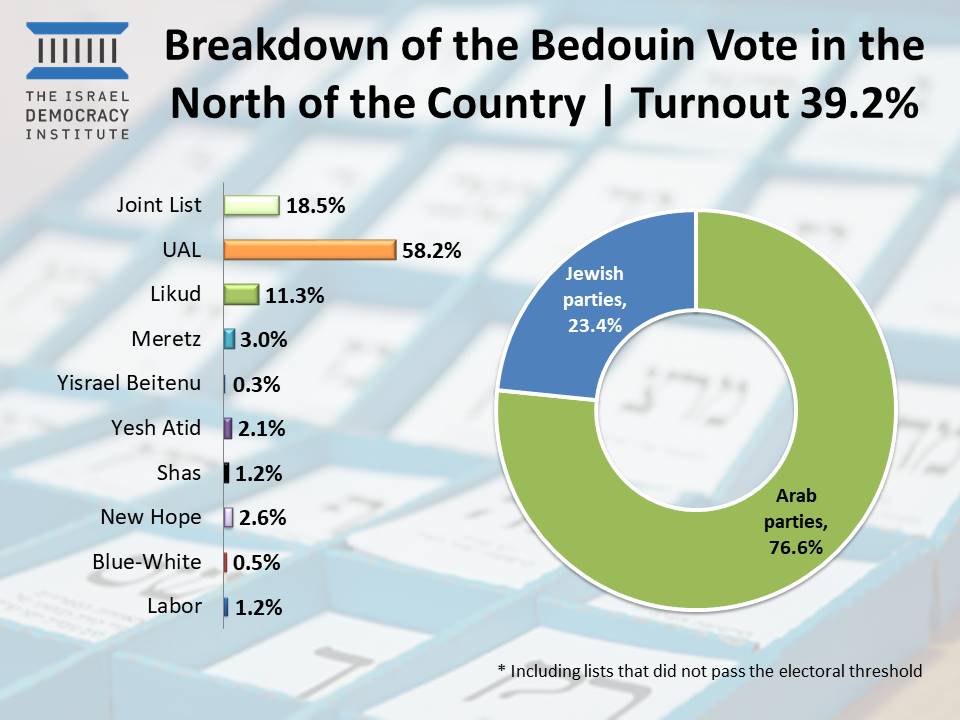

There were some variations among specific categories of Arab votes in the north. Most voters in the Galilee Bedouin settlements went for the UAL (58.1%), which came out far ahead of the Joint List (18.5%) and the Likud (11.3%). On the other hand, this sector’s turnout was very low (39.2%) compared with the average turnout in the overall Arab sector (44.6%).

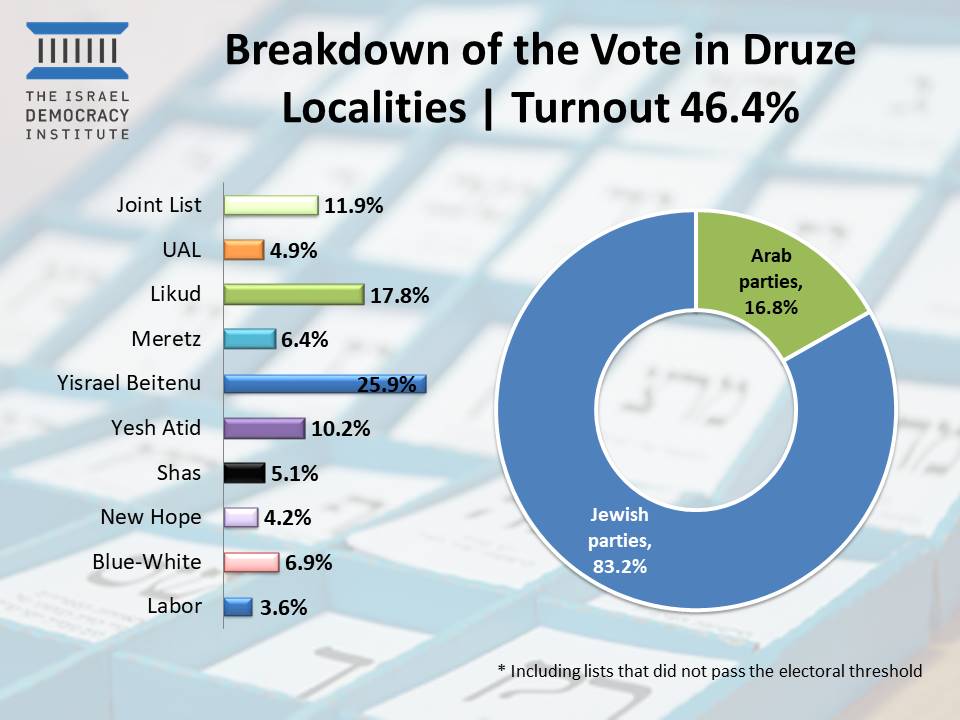

Turnout among the Druze (46.4%) was close to the overall figure for the Arab sector. The vast majority of the Druze population in Israel reside in 12 localities: nine that are almost exclusively Druze (95% or more of the residents), two with a large Druze majority (about 75%), and one mixed town, Maghar (60% Druze, 20% Muslims, and 20% Christians).

An overwhelming majority (83%) of the Druze vote went to Jewish parties, as is typical of the community’s voting behavior in Knesset elections. Here we can note an interesting development. Whereas Blue-White was dominant among the Druze in the three previous elections, this year their vote was more fragmented: Yisrael Beitenu took about a quarter of the Druze vote, followed by the Likud (17.8%) and Yesh Atid (10.2%). Votes for other Jewish parties were divided almost equally among Blue-White, Meretz, and Shas, with New Hope and Labor trailing behind.

The Joint List won 11.9% of the Druze vote, while Ra’am won only 4.9%. An interesting finding reveals that half of all the votes from Druze localities for the two Arab parties, came from Maghar. The town is home to Mansour Abbas, the head of the UAL, and Jaber Asaqla, a Druze member of Hadash (part of the Joint List). These “hometown favorites” explain the relatively strong support (51.4%) for the two Arab lists there.

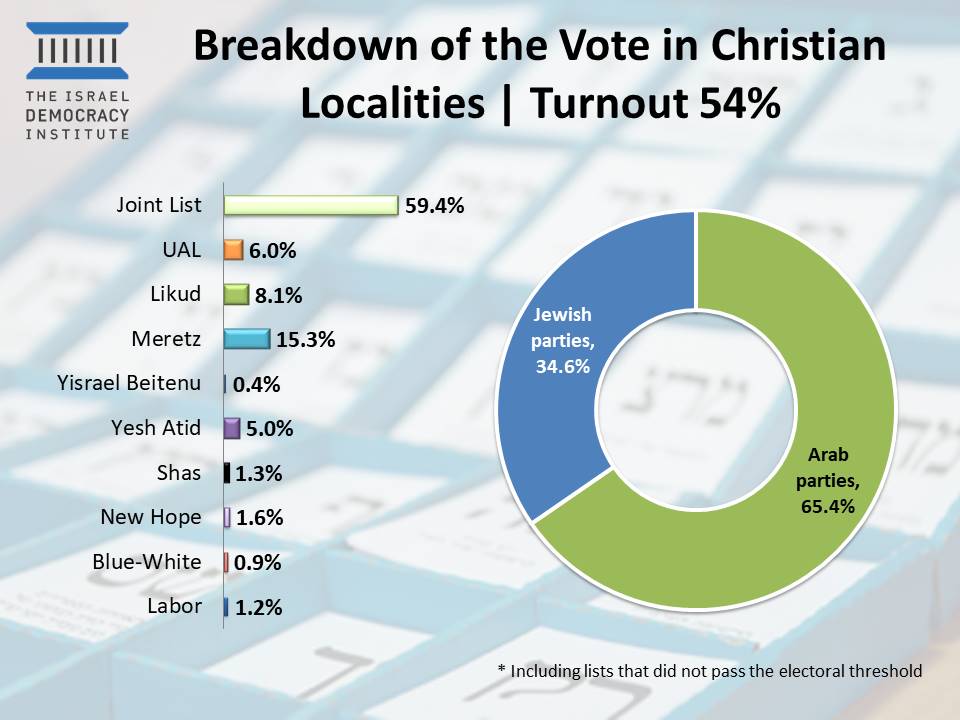

Turnout was relatively high (54.0%) in four small localities with an all-Christian population: Jish, Mi’ilya, Fassuta, and Eilabun. Most of their voters cast a ballot for the Joint List (59.4%); Meretz received 15.3%;, the Likud 8.1%, and the UAL 6.0%.

The Triangle

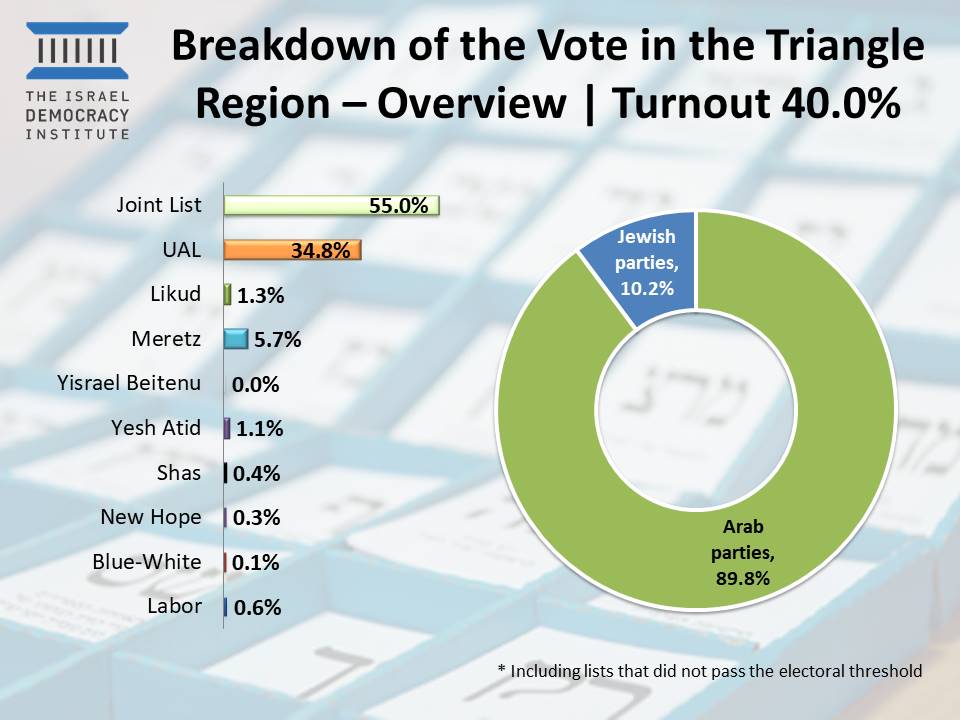

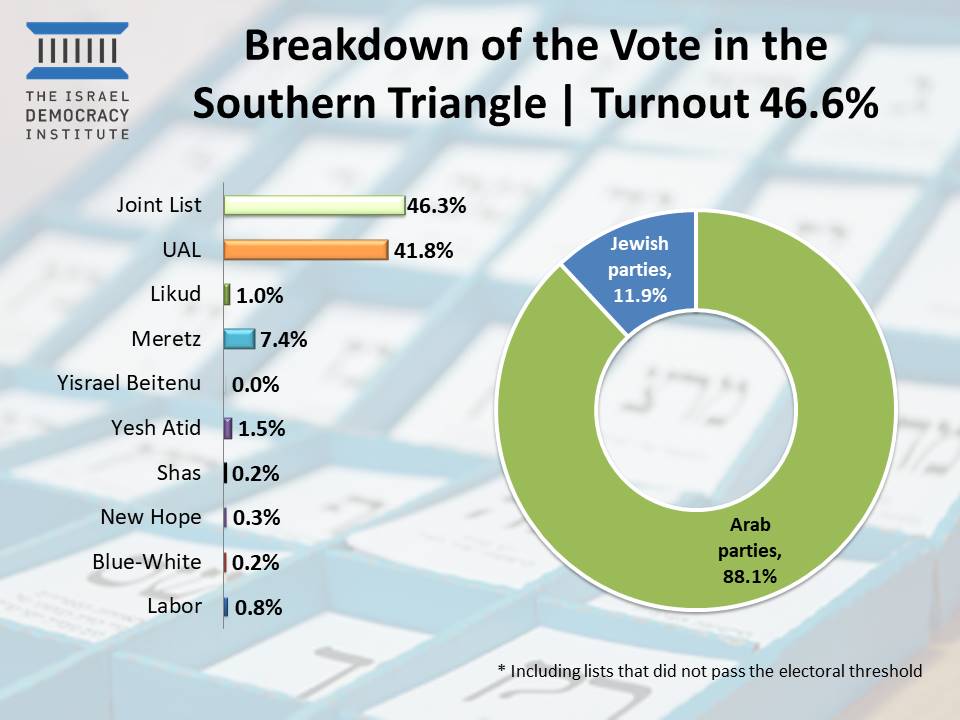

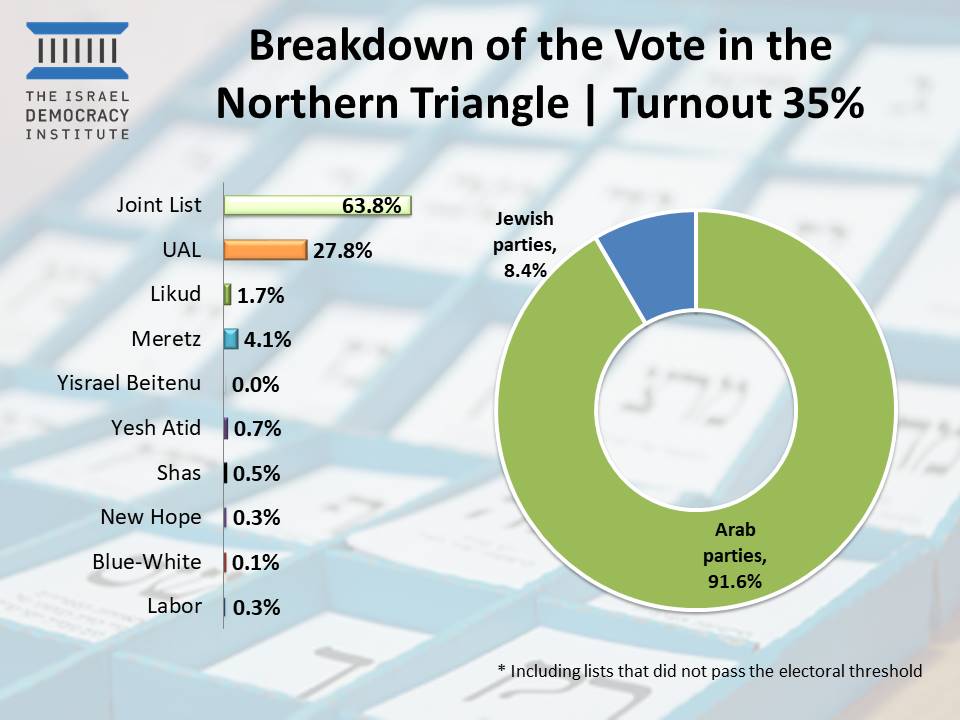

The Triangle region is where turnout plummeted most precipitously: only 40.0%, down from 68% in the elections for the 23rd Knesset a year earlier. In the northern Triangle, the figure was 35.0%; the 42.4% turnout in the southern part of the region was only slightly lower than the overall percentage for Arab localities.

As in previous campaigns, the vast majority of Arab voters (89.8%) again opted for the Arab parties. However, there were significant differences between the two parts of the Triangle. In the northern Triangle, almost two-thirds (63.8%) voted for the Joint List, and only 27.8% for the UAL. But in the southern Triangle, the two ran almost neck-and-neck: 45.7% for the Joint List and 41.8% for the UAL. This is because several large towns in the southern Triangle (especially Kafr Qasim) are Islamic Movement strongholds, which is the mainstay of the UAL.

Meretz was the leading Jewish party in the Triangle (5.7%), significantly outpacing the Likud (1.3%) and Yesh Atid (1.1%).

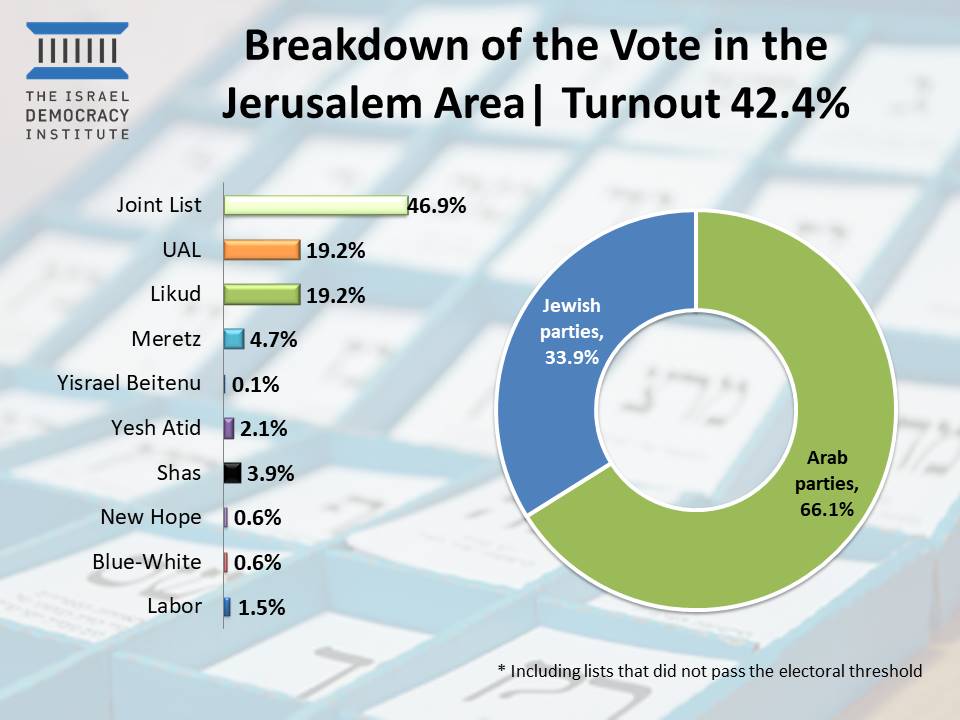

Arab Villages in the Jerusalem Corridor

The turnout in the three Arab villages in the Jerusalem corridor—Abu Ghosh, Ayn Rafa, and Ayn Naquba—42.4%—was close to the nationwide figure for the Arab sector. The Joint List took 46.9% of the vote, far ahead of the UAL and Likud, both of which received 19.2%.

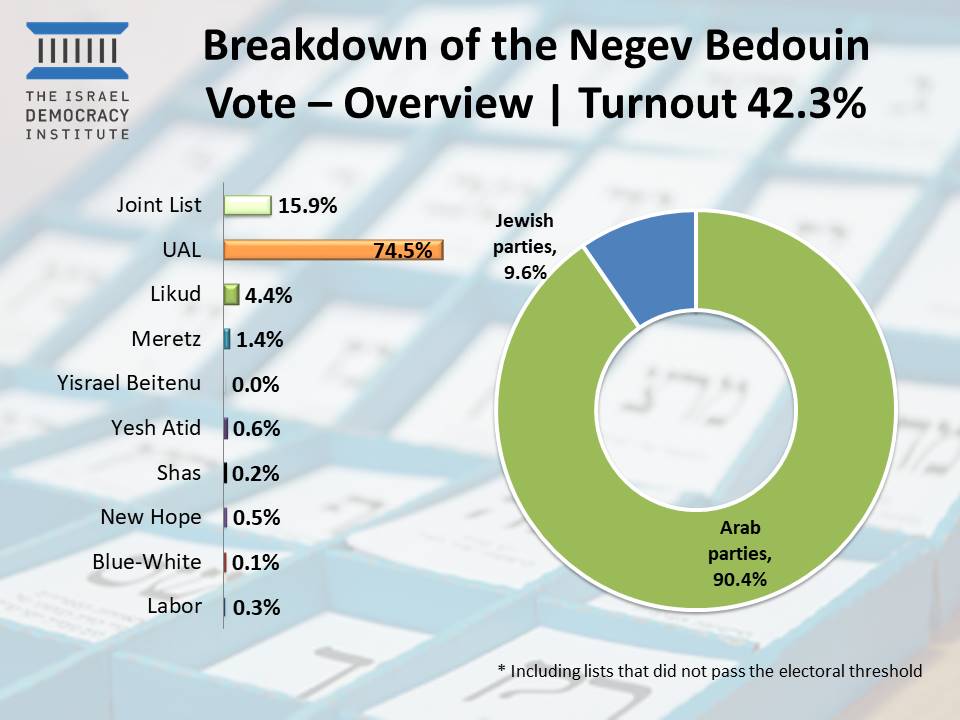

The Negev

In general, the turnout among Negev Bedouin is much lower than the nationwide average for Arab voters. This time, however, their participation was relatively strong, especially in the townships and permanent settlements affiliated with the regional councils. The main beneficiary was the UAL, which captured 74.5% of their vote—a quarter of its total for the country as a whole. The Joint List won a meager 15.8%, followed by the Likud with 4.4%.

The Negev Bedouins' support for the UAL (more than 42,000 votes) reflected the Islamic Movement’s strong presence among them. Whereas in previous elections the Bedouin’s relatively weak turnout did not provide the Arab lists with the equivalent of a Knesset seat, this time around, they provided the UAL with more than one seat, and in fact were a major factor in its clearing the threshold and gaining parliamentary representation.

Note that the Bedouins, both in the Negev townships and in the Galilee, turned out in force for the UAL, which led all other lists, including the Joint List, by a significant margin.

The Mixed Cities

Of the two Arab parties which ran in the elections, the Joint List was way ahead in mixed cities, winning some 28,000 votes (worth almost one Knesset seat). It was especially popular in Haifa and in Tel Aviv – Jaffa, where it picked up almost half of its total for the mixed cities. The UAL received only 7,000 votes.

In comparison with the elections for the 23rd Knesset, a year earlier, the four Arab parties that had made up the Joint List, this time—running as two separate lists, gained 20,000 fewer votes in the mixed cities. Their support fell back to the figure recorded in the elections for the 21st Knesset (April 2019).

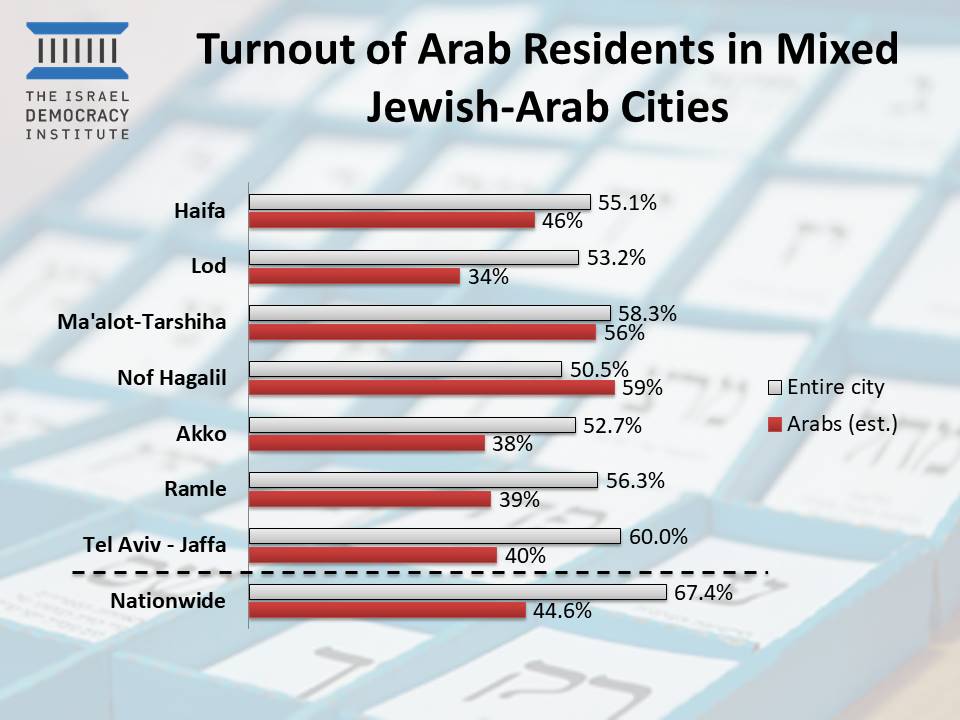

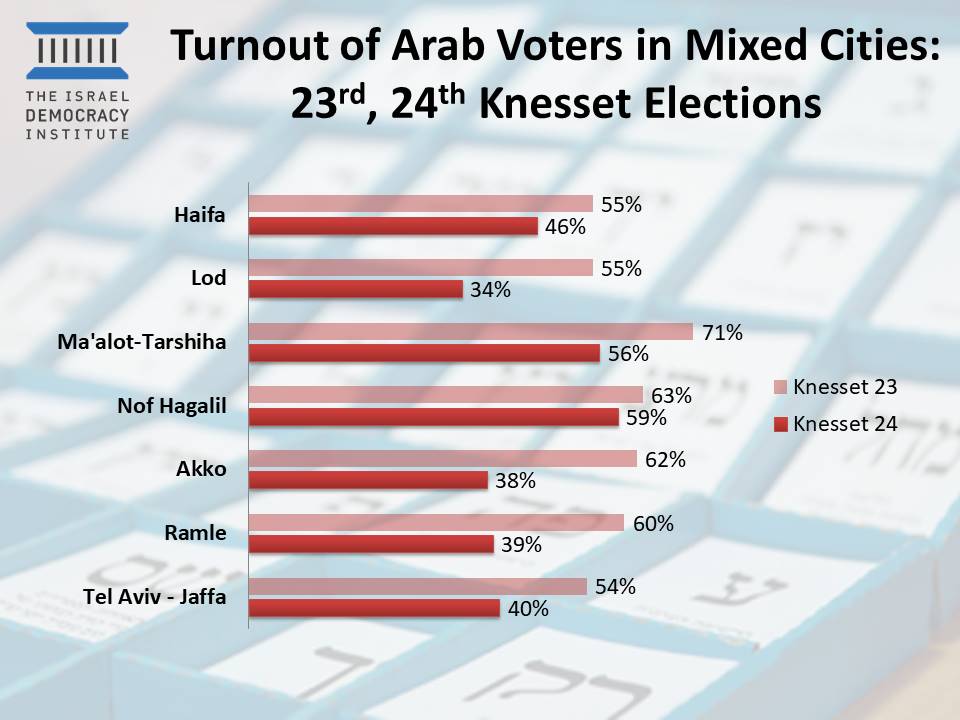

In mixed cities, Arab voter turnout was calculated on the basis of a sample of polling stations where the percentage of ballots for the two Arab lists was significantly greater than for the city as a whole, and similar to that elsewhere in the Arab sector (about 80%).

Based on the findings of this sample, Arab turnout in all the mixed cities was much lower than that of Jewish residents and also compared to the average turnout of Arab voters from predominantly Arab localities: 34% in Lod, 38% in Acre, and 39% in Ramle. In Jaffa, too, turnout was quite low (40%); the curious fact is that the combined support for the Arab lists did not exceed 67% in any of the ballot stations located in predominantly Arab neighborhoods in mixed cities —substantially below the 80% average in Arab localities.

Only in the mixed cities in the Galilee was Arab turnout relatively high—59% in Nof Hagalil (formerly Upper Nazareth) and 56% in Ma’alot-Tarshiha—on a par, or even slightly above the overall figure for these localities, and in any case—significantly higher than the average for Arab localities in the Galilee.

Compared to the elections of March 2020, there was a marked decrease in Arab turnout in all the mixed cities except Nof Hagalil. This drop was especially prominent in Lod, Ramle, and Acre – by 20 percentage points. This suggests that the combination of social and economic distress and frustration with the government is a recipe for political apathy.

The Arab Vote for Jewish Parties

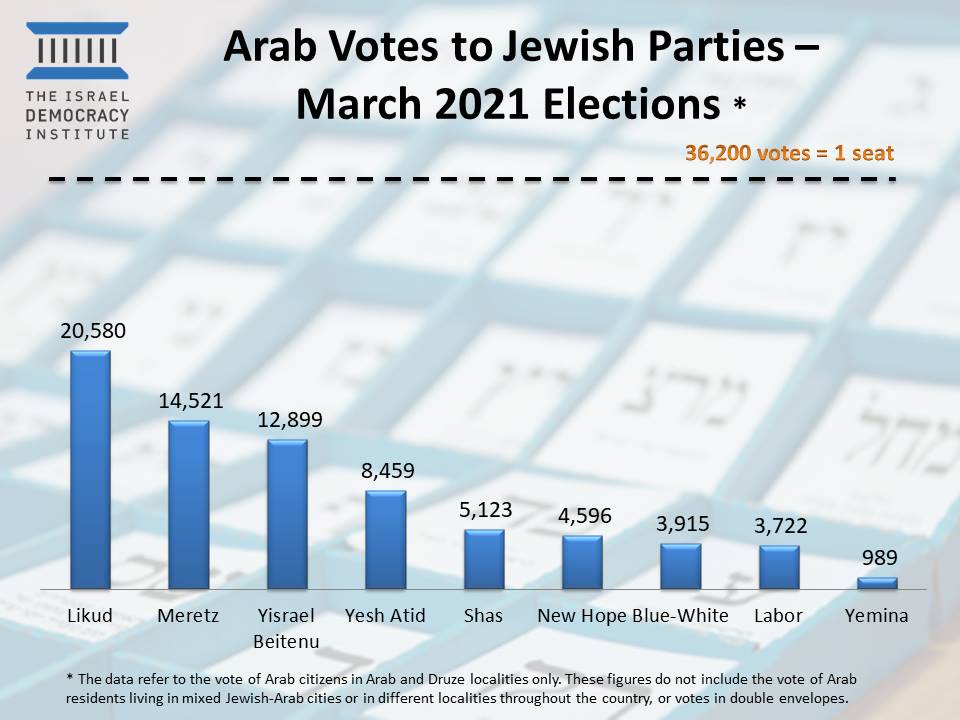

The attempts to brand Prime Minister Netanyahu as “Abu Yair,” (Yair's dad) does not seem to have brought the Likud significant Arab support. Arab voters gave the party roughly the equivalent of half a Knesset seat; Meretz and Yisrael Beitenu- about a third of a seat; and Yesh Atid, not quite a quarter of a seat.

Figure 18: Arab Votes to Jewish Parties – March 2021 Elections

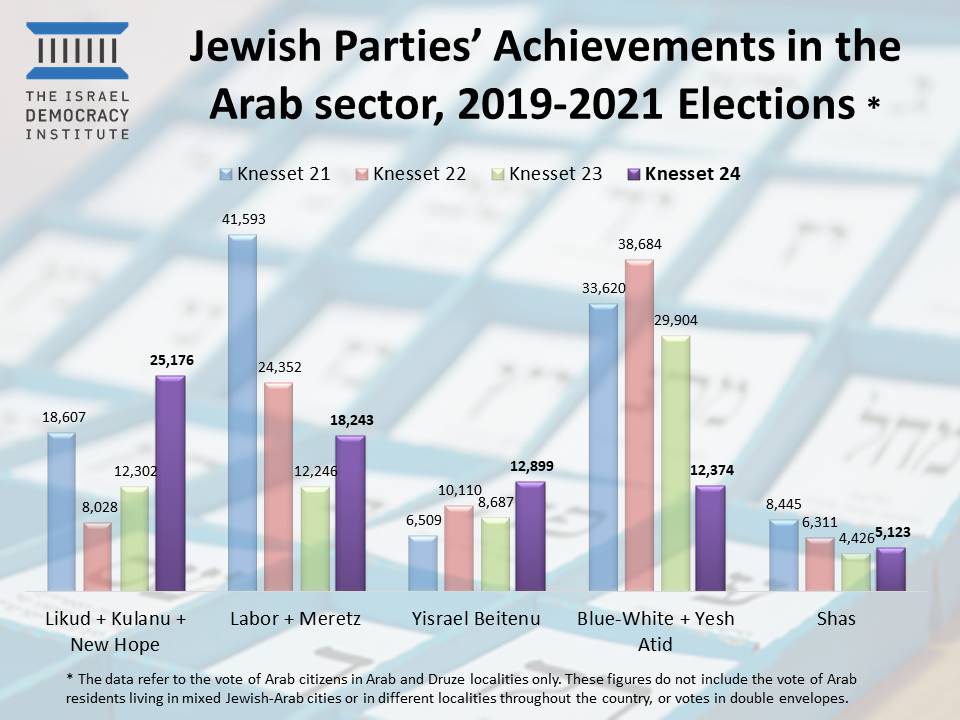

The recent trend of Arab voting for Jewish parties reveals a clear shift towards the right. There has been an increase in support for the Likud and lists that split from it (New Hope) or were associated with it (Kulanu). Arab support for Yisrael Beitenu has doubled over the last two years (the number of eligible voters in the Arab sector grew by only 6% in the same period, so that this is a significant increase). Two Druze were elected to the Knesset this year, one each on the Likud and Yisrael Beitenu slates. By contrast, there has been a dramatic collapse of Arab support for centrist (Blue-White) and leftwing (Labor and Meretz) Jewish parties.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to point to a renewed connection between the Arab voter and Jewish right-wing parties, or between the Arab voter and the Jewish parties in general, since in this election there was another slump in support for Jewish parties among all eligible voters in Arab localities. The fact that the rate of support for Jewish parties in this election was similar to the rate of support in them (8%) in the 2020 election, in which the Arab turnout in Arab society was particularly high, shows that support for Jewish parties on the Arab street does not depend on Arab citizens' participation in elections, and is consistently low. In other words, the stronger the sense among Arab citizens that they may have political influence in a particular election campaign, the more motivated they will be to participate in them, with the main beneficiaries being the Arab parties, since Arab citizens believe that the Arab parties have a greater capacity to provide Arab citizens with political influence, than do the Jewish parties. This conclusion explains why, despite the Likud's aggressive advocacy campaign in the last election, Prime Minister Netanyahu's appeal to Arab citizens to directly influence government policy by voting for the ruling party (that is—a large Jewish party) fell on deaf ears and did not yield significant Likud achievements.

Nevertheless, Arab representation in Meretz reached an historic peak: for the first time the party sent two Arabs to the Knesset. This achievement can be credited to the party’s Jewish voters, who in a sense were repaying a debt to the Arab sector that was giving / that had given / that gave it an entire Knesset seat in April 2019 and making it possible for it to cross the electoral threshold. Labor, too, placed an Arab in the Knesset for the first time in two-and-a-half years (after Zoheir Bahalul quit the party to protest the passage of the Nation-State Law and no Arab candidate was high enough on its list to make it to the Knesset in the three elections of 2019 and 2020).

Arab voters provided Jewish parties with the equivalent of two Knesset seats—slightly more than one to the rightwing parties, and slightly less than one to the center-left parties.

Conclusion

Despite the (relative) success in passing the electoral threshold, the Arab parties cannot rest on their laurels and ignore the fact that half of the Arab public did not vote.

The Joint List will have to engage in serious soul-searching and figure out why it paid the price of the UAL’s secession ahead of the campaign. It is very likely that this can be attributed to the fact that over the past two years it has sought to position itself as a clear opposition party whose main political influence is reflected in thwarting Netanyahu's efforts to gain the support of the majority needed in the Knesset to form a government under his leadership. The achievements of Knesset members from the Joint List in the parliamentary process in recent years should be acknowledged, but the fact that growing circles of the Arab public are now having difficulty defining their political orientation on what until now has been the left-right axis has dealt a blow to the Joint List.

Whether the Joint List will retain its current make-up is an open question. Hadash is desperately trying to figure out how they lost their top status as representatives of the Arab public in the Knesset and how the dominant position of the party on the Arab street has been eroded, even though Hadash members have been adamant in maintaining the framework of the Joint List. Balad is having a hard time digesting the party's drop in its political representation in this election (one representative). Party members, present and past, are now calling for a reorganization of the party's ranks – with regard to its national and political discourse, the contact between the party's leadership with its past supporters, and the connection between the party and the general Arab public.

On the surface, the UAL is the big winner on Election Day, but it will have to maneuver with great caution between its desire to brand itself as an independent Arab party in pursuit of its political goals, on the one hand, and the need to avoid being fixed in the public mind as the stepchild among the Arab parties, on the other. The main question is whether it will realize its strategic objective of forming an alliance with whatever government is formed so as to influence its policy towards the Arab sector. If a government is formed with the support of Ra’am, and more importantly - if the demands it presented on the eve of the election for boosting the social and economic situation in Arab localities are accepted, then the results of the last election can be viewed as a watershed moment in Arab politics in Israel.

The recent elections proved, once again—especially against the backdrop of the Joint List’s meteoric success a year ago—the weakness of the parties’ base on the Arab street. This is why these parties need to keep reinventing themselves, forming and dissolving alliances in order to suit the public mood, rather than expecting the public to follow them—come what may.

Paradoxically, it is precisely the dead-end in which the Israeli political system now finds itself that has given the Arab vote decisive weight. But the Arab vote—whether for an Arab list or a Jewish party—cannot be taken for granted. The question is what party will be astute enough to devise a political agenda that can alleviate the Arabs’ mounting frustration and restore their belief in the value of active participation in the country’s parliamentary system.