Are the Presidential Elections: A Political Race for a Ceremonial Position?

As Israel approaches the election of its 11th president, Prof. Ofer Kenig surveys the results of past presidential elections and argues that although the role of the Israeli president is largely ceremonial, the race for the position is partisan and political.

Flash 90

Introduction

The elections for the President of Israel take place for a position that is mainly symbolic and ceremonial. While it is true that the President holds several substantive powers, at the end of the day, he is a figure that transcends party politics, political disputes, and the internal divisions in Israeli society. Nevertheless, it is difficult to ignore the fact that the presidential race is somewhat political in nature, both because most of the presidential candidates and all of the presidents to date (with one exception)) were identified with a specific political party, and because the Israeli president is elected by the members of the Israeli parliament.

This explainer reviews Israel's 16 presidential elections, from the election of Chaim Weizmann in 1949 to the election of Reuven Rivlin in 2014. It examines which of the races were a clear struggle between a candidate supported by the ruling coalition and a candidate supported by the opposition and examines the number of candidates who competed, the number of rounds of voting that were required, and the majority received by the president who was elected.

What Can We Learn from Israel's 16 Presidential Elections?

Israel's first presidential elections were held in February 1949, a few days after the Constituent Assembly ratified the Transition Law and declared itself the First Knesset. There were two contenders for the position: Chaim Weizmann, who had the support of the Mapai (the Labor Party), the General Zionists, and a few other parties, and Joseph Klausner, who was considered the candidate of the Revisionist movement. Weizmann was elected in the first round by an overwhelming majority of 83 votes, against 15 votes for Klausner.

Less than three years later, in November 1951, elections were again held for President. At that time, the presidential elections were linked to the Knesset's term, and since the first Knesset was dissolved before the end of its full term, new presidential elections were necessary. Although Weizmann was in poor health at the time, he ran again for the position. Since there were no other candidates, the members of Knesset were given the opportunity to vote either for or against Weizmann's candidacy. A total of 85 MKs voted in favor of Weizmann, and 11 were opposed. Following this, it became an accepted practice that when an incumbent president ran for an additional term in office, Israel's political parties refrained from putting forward an alternative candidate.

Following Weizmann's death, Israel's third presidential elections were held in December 1952. This race was the most competitive of all, both in terms of the number of candidates and in terms of the number of rounds of voting that were necessary. Three of the four candidates for president were members of the Knesset at the time: Yitzhak Ben Zvi (Mapai – Labor Party of Eretz Yisrael), Mordechai Nurock (Mizrachi), and Peretz Bernstein (General Zionists). The remaining candidate, Yitzhak Gruenbaum, had the support of Mapam (United Worker's Party) and Maki (Israel Communist Party). In the first round, Ben-Zvi received 48 votes, while the other three candidates each received a similar number of votes (15, 17, and 18). Since no one received a majority of at least 61 Knesset votes, a second round was held, and when it emerged that there was little change in the breakdown of the votes, a third round took place. Between the second and third rounds, Bernstein announced his withdrawal from the race, and the representatives of the General Zionists transferred their support to Nurock. A big surprise, however, came from Mapam—then the chief opponent of Mapai—whose representatives decided to transfer their support to Ben-Zvi, the Mapai candidate, in the third round. This move gave Ben-Zvi the necessary majority with a total of 62 votes.

In accordance with the practice that was established in 1951, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi was re-elected for a second term without any other contenders in October 1957 (76 MKs voted in his favor) and for a third term in October 1962 (62 voted in his favor). Ben Zvi was the only Israeli president to be elected to three terms in office. In 1964, a Basic Law was enacted that limited a president's term of office to two terms.

Six months after his election to a third term, Ben-Zvi died, and in May 1963, elections were held for the third president of Israel. There were two candidates for the position: former Mapai MK Zalman Shazar, the candidate of the coalition and ruling party (Mapai), and MK Peretz Bernstein of the Liberal Party, who was considered the opposition candidate. Shazar was elected in a single round, with a majority of 67 votes (vs.33 for Bernstein). He was elected for u a second term in March 1968 uncontested, with 86 MKs supporting his candidacy.

The elections for Israel's fourth president in April 1973 were exceptional in that they included two candidates who were both from outside of the world of politics. Nevertheless, the race was political in character, since each of the candidates was identified with a large political party. The scientist Prof. Ephraim Katzir was the candidate of the ruling party (Ma'arach – Labor Alignment), while his opponent, Prof. Ephraim Elimelech Urbach, had the support of the major opposition party (Gahal – Herut-Liberal Bloc) and of the National Religious Party (NRP), which was then part of the coalition. Katzir received a clear majority of votes from 66 MKs in the first round of voting, as opposed to 41 votes for Urbach. Katzir decided not to run for a second term as president, choosing to return to his work as a scientist.

Elections for Israel's fifth president were set for April 1978. These elections had special significance in that for the first time, the Likud was the ruling party. While Likud was expected to successfully run a candidate of its choosing, it became clear that things were not so simple. Prime Minister Menachem Begin proposed nominating Prof. Yitzhak Shaveh, a relatively unknown figure whose candidacy was controversial. In the end, Prof. Shaveh decided not to run and MK Yitzhak Navon, the representative of the opposition party Ma'arach, was elected uncontested, receiving 86 votes. Like Katzir, Navon also chose not to run for a second term in office.

Elections for the sixth president were set for March 1983, during the second government of Menachem Begin. For the second consecutive time, the ruling party failed to secure the election of its preferred candidate. This time, however, there was a very close contest. MK Chaim Herzog, the candidate of the main opposition party (Ma'arach), ran against Menachem Elon, a scholar of Jewish law and Supreme Court Justice who ran as the candidate of the right wing and religious bloc, in the closest elections until that time. Herzog, the opposition candidate, received a surprising 61 votes and was elected the sixth president of the State of Israel.

Herzog ran for a second term, and in accordance with the tradition that had been established over the years, he was elected uncontested in February 1988. He received the support of 82 MKs.

Five years later, in March 1993, elections were held for Israel's seventh president. The Labor Party, which was then the ruling party, supported former MK Ezer Weizman, while the Likud party candidate was MK Dov Shilansky. When the votes were counted, however, there was great embarrassment when 124 voting slips were found in the ballot box—four more than the total number of Knesset members. The Knesset Speaker ordered a revote, in which Weizman was elected to the position with a majority of 66 votes to 53.

Five years later, in March 1998, Weizman ran for a second term. This time, however, the longstanding tradition was broken, and the Likud, which had returned as the ruling party in the meantime, put forward a candidate to run against an incumbent president. Although Weizman won in the first round, receiving 63 votes as compared to the 49 received by Likud's Shaul Amor, the fact that an incumbent president was dragged into a political reelection campaign was one of the main causes that led to an amendment of the Basic Law limiting future presidents to a single term, which was extended to seven years.

Two years after being elected to a second term in office, Weizman resigned his position. Elections for the eighth president were held in July 2000. Minister and former Prime Minister Shimon Peres was the candidate of the ruling party (One Israel), but Ehud Barak's crumbling coalition was not able to ensure his election. The Likud put forward MK Moshe Katzav. At the end of the first round of voting, there was great surprise when Katzav received 60 votes as opposed to 57 for Peres. This majority was not sufficient for his election, and so a second round was held. This time Katzav gained three additional supporters and was elected president with a majority of 63 to 57.

The elections for the ninth president of Israel were held in June 2007. This time, for the first time since 1952, there were more than two candidates. The ruling party, Kadima, put forward Minister Shimon Peres, who had previously been a presidential candidate for One Israel, as its presidential candidate. The Likud's candidate was MK Reuven Rivlin, while the Labor Party decided to support the candidacy of MK Colette Avital, the first woman to run for presidency. In the first round, Peres received 58 votes, as opposed to 37 for Rivlin and 21 for Avital. The Knesset prepared for a second round, but before it was held, Avital, followed by Rivlin, withdrew from the race. With only one candidate remaining, Shimon Peres was elected President, with 86 votes in his favor and 23 votes against.

To date, the last elections, were held in June 2014 and were the most competitive in terms of the number of candidates. Six individuals succeeded in garnering the 10 required nomination signatures. Three of those were incumbent MKs: Reuven Rivlin (Likud), Meir Sheetrit (Hatnua) and Binyamin Ben-Eliezer (Labor). The other candidates were Dalia Itzik (former politician), Dalia Dorner (former supreme court judge) and Prof. Dan Shechtman (winner of Nobel prize in Chemistry). A few days before the elections, Ben-Eliezer quit the race. Although Rivlin was formally the candidate of Likud, he did not enjoy the automatic support of all its members. In fact, Prime Minister Netanyahu tried to prevent the election of Rivlin, by seeking another candidate and even toying with the idea of canceling the presidency. These circumstances, together with the multiple candidates, produced a unique race which did not follow the line of coalition versus opposition candidates. In the first round, Rivlin won the support of 44 MKs. Sheetrit (31) and Itzik (28) competed for second place. In the second round, Rivlin was elected after receiving 63 votes.

2014 presidential elections results

| 1st round | 2nd round | |

| Reuven Rivlin | 44 | 63 |

| Meir Sheetrit | 31 | 53 |

| Dalia Itzik | 28 | |

| Dalia Dorner | 13 | |

| Dan Shechtman | 1 | |

| Total | 117 | 116 |

Competitive Elections or a Race with a Predetermined Outcome?

In six of the 16 presidential elections in Israel, there was no formal competition, since there was only a single candidate. In five of those instances, an incumbent president was running for an additional term of office. As noted, the accepted practice in the Knesset from as early as 1951 was not to propose a candidate against an incumbent president.

The Elections for President of Israel, 1949–2014

| # of candidates | # of rounds | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 1951 1957 | 1949 1963 | |||

| 1962 1968 | 1973 1983 | ||||

| 1978 1988 | 1993 1998 | ||||

| 2 | 2000 | 2007 | 2014 | ||

| 3 | 1952 |

In seven of the election campaigns, the race was a head to head competition between two candidates. Generally only a single round of voting was necessary to determine the winner. An exception to this was the presidential election of 2000, when Moshe Katzav lacked only one vote to be elected in the first round, therefore necessitating a second round of voting.

In the three election campaigns with multiple candidates, it was also necessary to have more than one round of voting. In the two last elections (2007, 2014) none of the three candidates managed to achieve a majority of 61, which necessitated a second round. In 1952, when there were four competing candidates, three rounds of voting were necessary until Yitzhak Ben-Zvi secured his victory.

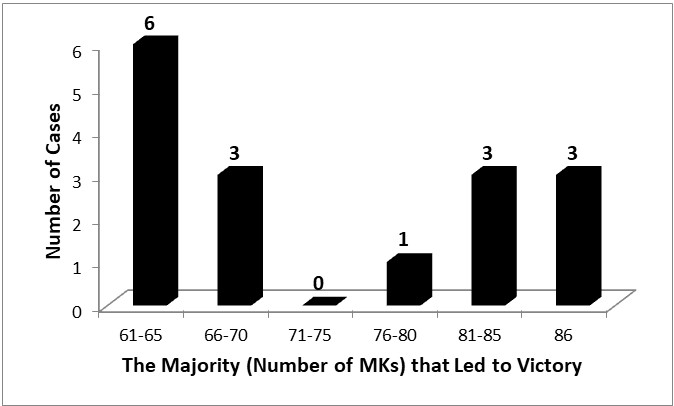

The president who was elected by the narrowest majority is Chaim Herzog in 1983 – 61 votes against 57 for his opponent. Three candidates were elected by the biggest majority of 86 MKs: Shazar (1968), Navon (1978) and Peres (2007). An examination of the distribution of the majority vote (Figure 1) reveals an almost even number of close races, in which the president was elected by a majority of up to 70 members of Knesset, and cases in which the president was elected with a solid majority of at least 76 members of Knesset. The latter were elections for a second term in office or elections in which there was a single candidate, whether from the outset (e.g., Navon in 1978) or as a result of the withdrawal of other candidates (e.g., Peres in 2007). The conclusion to be drawn from this is clear: When the Knesset elects a new president and there is more than one candidate, there is a very high probability that the race will be close.

Distribution of the Majority by which a President is Elected

Political Elections for a Ceremonial Position

The Israeli presidential electoral system places a fairly high entry barrier to the race. A potential candidate must obtain the signatures of at least 10 members of Knesset in order to run. It is therefore not surprising that the contenders are always candidates put forward by a particular party or a group of parties. Even the few candidates from outside of the political arena, such as Ephraim Katzir and Menachem Elon, were supported by a party or a group of parties. Large parties that see themselves as contenders for the government put forward their own candidate for president to demonstrate their presence and as an expression of their political power and public standing. This is especially true for the governing party, which heads a coalition that is expected to give it a majority and lead to the election of its candidate for president.

As we have seen, however, in four cases the ruling party did not succeed in getting its candidate into office. When the Likud was in power in 1977–1984, Yitzhak Navon and Chaim Herzog, who were both candidates of the Labor Party, were elected president. Ezer Weizmann's election for a second term in 1998 came also at a time when the Likud was in power and had put forward its own candidate. In 2000, when the One Israel party (an alliance of Labor, Meimad, and Gesher) was in power, it was the Likud candidate, Moshe Katzav, who was elected.

How can these failures of the ruling parties be explained? One possible explanation can be found in the fact that the elections are conducted by secret ballot and are for a symbolic, ceremonial position. It may be that Knesset members in the voting booth diverge from the official party line and vote for a candidate by virtue of his or her own merit. Another explanation emphasizes the political aspect of the presidential elections. Since the presidential elections take place during the term of a Knesset, they are an opportunity for a protest vote, particularly when there is criticism of the ruling government and the ties between the coalition partners are not particularly strong.

This may explain the Likud's failure to bring about the election of Menachem Elon in 1983. The surprising victory of the opposition's candidate Chaim Herzog at that time, reflected the fragility of Begin's coalition: The elections took place in the shadow of the First Lebanon War, a short time after the publication of the Kahan Commission of Inquiry report on the events that took place at the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla, the murder of Emil Grunzweig, and the removal of Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon from his position. Shimon Peres's surprising loss to Moshe Katzav, the opposition candidate in 2000, can be explained in a similar manner. The elections took place a short time after Prime Minister Ehud Barak's return from the Camp David Summit. Not only had the talks failed, but Barak's decision to attend the summit in the first place had accelerated the weakening of his crumbling coalition to the point that on the day of the presidential elections, the government was already virtually a minority government. At that time, a number of Knesset members used the presidential elections as an opportunity to protest against the government and against Barak's leadership style, and Peres was the victim. These cases are good illustrations of the fact that presidential elections in Israel cannot be isolated from the reality of party and political considerations.