Term Limits for Israel's Prime Minister?

The recently proposed bill would limit the tenure of the Prime Minister in Israel to eight years (continuous or cumulative). At the end of that time, the Government would be considered to have resigned and its head would no longer be eligible to serve as Prime Minister. This limitation would apply only to tenure after the date of the law’s passage.

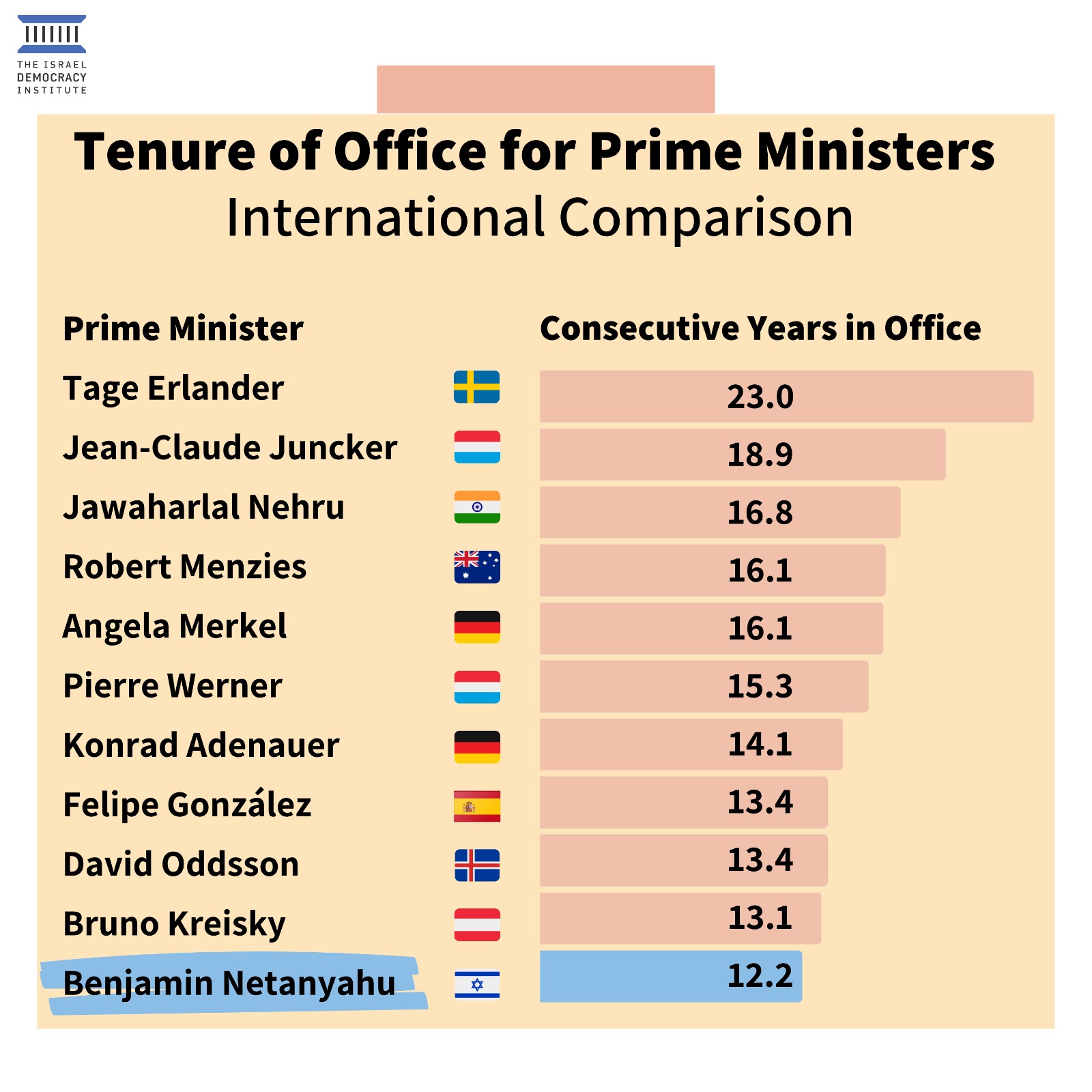

Longest Continuous Terms of Office of Prime Ministers of Parliamentary Regimes since World War 2 (as of October 31, 2021)

Graph by: Prof. Ofer Kenig

Benefits and Justifications

• Such a law would avert the danger posed by the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the Prime Minister. The concentration of too much power in the hands of a single body or individual can threaten the institutional pillars of democracy and runs counter to the principles of liberal democracy, which is based on the idea of the decentralization of power and the existence of checks and balances.

Although traditionally this has been viewed as very small danger in parliamentary regimes such as Israel’s, it has increased in recent years, when a number of parliamentary democracies have seen the power and authority of the prime minister grow in a process that is known as “presidentialization.” This has taken place in Israel, too, manifested in the increased power of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office vis-à-vis others players such as his political party, the Knesset, the Government, and the various ministries.

• It would encourage competition and a turnover in office, salient elements of democracy. There are two main reasons for the current need for measures to encourage competition and turnover: (1) the Prime Minister’s progressive accumulation of power; (2) for over a decade, there was no handover of power in Israel decade. Former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s tenure in office was the longest in the history of Israel.

• The bill is neither personal nor retroactive. The calculation of a Prime Minister’s maximum tenure will begin only after the law has taken effect. Consequently, it would not bar previous prime ministers (including Netanyahu) from returning to office.

Disadvantages and Dangers

• There is no comparative precedent and the idea of term limits is not compatible with Israel's system of government. Term limits are foreign to parliamentary democracies. We are not aware of any parliamentary democracy with a structure similar to that in Israel that has limited the tenure of the head of the executive branch. Such term limits are found in South Africa and Switzerland, which are parliamentary democracies, but whose governmental systems are totally different from Israel’s. Among other things, in Switzerland the head of the executive branch changes every year; in South Africa, he holds the dual role of head of the executive branch and head of state, and thus in practice his role and powers are much more similar to those of the leader of a presidential democracy.

Term limits are popular in presidential regimes (in some 84% of presidential and semi-presidential regimes), which are distinguished from parliamentary regimes in two main ways: (1) In a parliamentary system, the prime minister wields fewer powers, and his or her public legitimacy is less than that of the head of a presidential regime. (2) In a presidential regime, the president’s term of office is fixed and known in advance (such as four years in the United States), but in a parliamentary democracy it is impossible to know in advance how long a prime minister will hold on to office.

In the absence of a model for comparison of how term limits work in parliamentary democracies, there are grounds for the fear that it might produce serious problems or complex constitutional lacunas—situations that no one can foresee, making it plausible that the legislation will not provide ways to deal with them.

• It would undermine political stability: According to the draft bill, when the Prime Minister reaches his term limit, the government he heads will be deemed as having resigned. If this happens, as is likely, in the middle of a Knesset term, it would destabilize the government, which would have to be reformed in the middle of the Knesset’s term. It is also possible that the process of forming a new government would fail, leading to early general elections.

• It would be a blow to governance: In a government that takes office with the knowledge that it will have to resign at a known date and that the Prime Minister will have to be replaced at that time, the Prime Minister will be a lame duck whose term is overshadowed by battles among those who claim to be the heir apparent.

• It would be easy to dodge the term limit. Similarly to the law as a whole, the sections on term limits in the amended Basic Law: The Government could be amended by a Knesset majority—61 members; this means that almost any future coalition would be able to discard the term limit. The experience of recent years has shown that the Knesset does not hesitate to revise Basic Laws to suit political needs. In this context, it is impossible to ignore the danger that, if enacted, the term limits law would be repealed when necessary. A look at other countries reveals that in presidential regimes, presidents who run into term limits, do indeed attempt and often succeed in eliminating or evading this obstacle. A 2020 study found that since the beginning of the century, in 26% of the cases in which presidents in presidential and semi-presidential regimes faced a term limit, they made efforts to evade it; and in two-thirds of those cases they succeeded in doing so.

• Clearly the bill would set limits on the will of the majority-- a highly significant democratic principle which should be curtailed only if there is a strong rationale and for a highly significant purpose. It also places something of a limit on the right to vote and be elected.

• Empirical studies do not provide clear-cut proof that term limits reduce corruption, encourage better policy planning, and help foster higher quality leaders in the long run. There are even studies that assert that term limits have the opposite effect (chiefly with regard to corruption). This is because an elected official who knows that this is his last hurrah, with no possibility of being reelected, will have no interest to work on behalf of the public in order to remain in power; on the other hand, he or she will have good reason to promote the interests of tycoons and others who can support him financially after he leaves office.

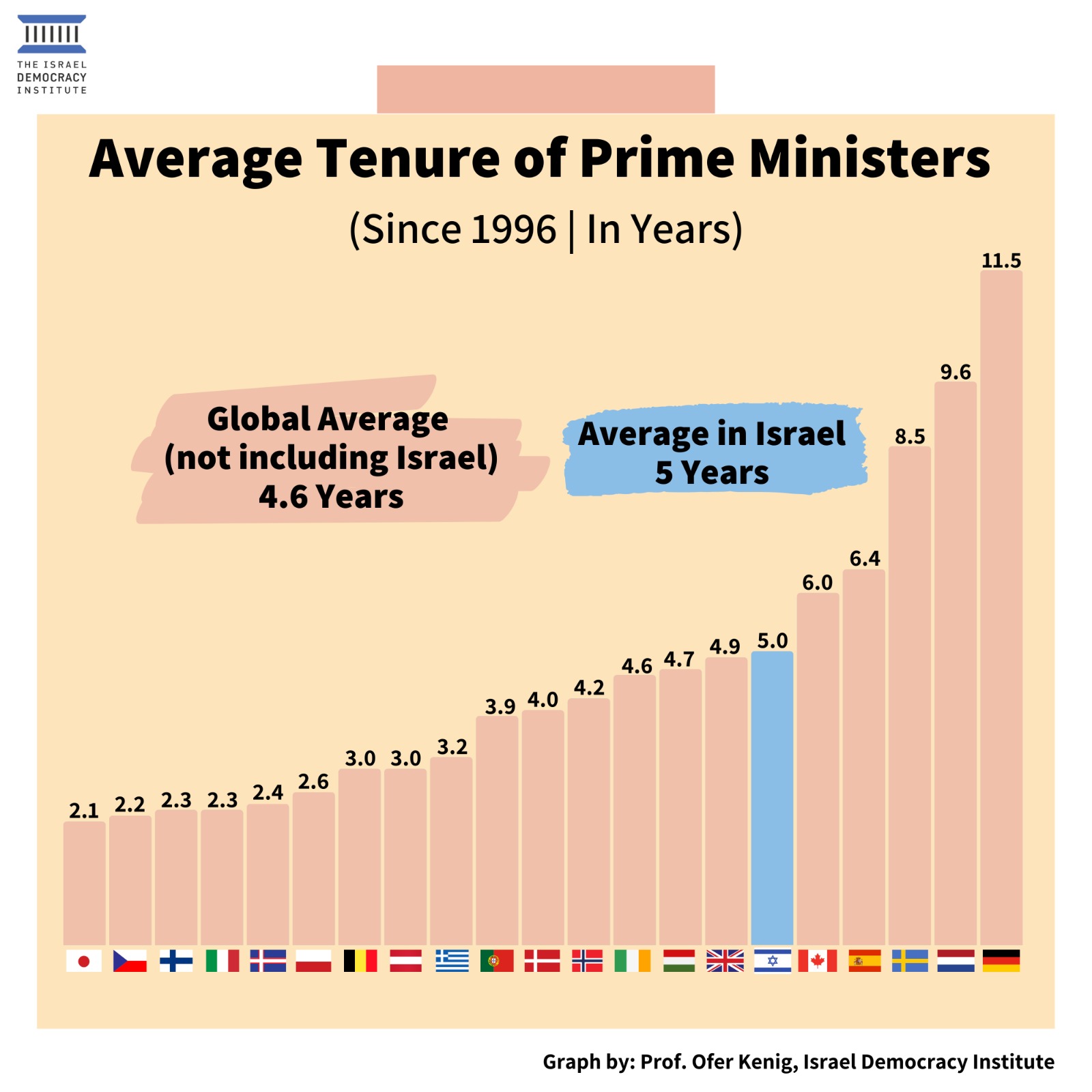

A Comparative and Historical Look at the Length of Prime Ministers’ Tenure

Despite Netanyahu’s long years in office, Israel does not suffer from an extreme lack of turnover in power. Looking back, no Prime Minister, with the exception of Ben-Gurion and Netanyahu, has served the maximum term that would be allowed under the bill. Yitzhak Shamir, Yitzhak Rabin, and Menachem Begin, all served less than seven years, and the others –for even shorter periods.

From a comparative perspective, even Netanyahu’s long tenure is not extreme; at least 11 prime ministers of parliamentary democracies have served longer continuous terms. The prominent current example is Angela Merkel in Germany, who has held her post continuously since 2005 and will be leaving office soon. In addition, many recent prime ministers in other countries have served terms only slightly shorter than Netanyahu’s: Mark Rutte (the Netherlands) has been in office for the last 11 years; Stephen Harper (Canada) was in office for almost a decade (2006–2015); in New Zealand, two prime ministers of recent times served more than eight years each (Helen Clark, 1999–2008 and John Key, 2008–2016). Even in years gone by there were continuous terms exceeding a decade, such as Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain (1979–1990) and Pierre Elliott Trudeau in Canada (1968–1979).

Recommendations

We cannot take an unequivocal position on whether the bill’s advantages outweigh its disadvantages. However, we would like to propose what we consider to be essential changes in its provisions.

• The legal situation of a Prime Minister who reaches his or her term limit must be clarified. In particular, it should be added that in this situation:

• The President will begin the procedure for forming a new government.

• The outgoing government will continue in office until a new government is installed, in keeping with the principle of government's continuity.

• Nevertheless, the Prime Minister himself will be replaced by another member of the government, following the rules that apply when a Prime Minister dies in office, is permanently unable to perform his duties, or has been removed from office due to a criminal conviction: “The Government will name another minister who is a member of the Knesset and a member of the Prime Minister’s faction to serve as acting Prime Minister until the new government is formed.”

• We believe that amendment of Basic Laws should require a large Knesset majority, and this should be done within the framework of Basic Law: Legislation, when it is enacted. Until then, so that an article such as the one discussed here, on term limits, will not be purely declarative and subject to revision and change, the specific articles dealing with term limits within Basic Law: the Government should be protected by the requirement of a supermajority—perhaps even 80 Knesset members—for its amendment.

• Consideration should be given to defining a “cooling off period” for a Prime Minister who has left office due to term limits, after which he or she could again serve as prime minister. Such a period is stipulated for presidents in some presidential regimes that have term limits (between 15% and 20% of them, such as Argentina and Brazil).

We think this is a good idea for a number of reasons. First, as empirical studies have shown, it increases the likelihood that presidents who have reached their term limits will leave office "smoothly" instead of trying to do away with the term limit, knowing that they will be able to return to office in the future. Second, it is clear that such a cooling-off period is a more proportionate restriction of the right to vote and be elected, and of the democratic principle of majority rule.

All the same, such a mechanism increases the danger that a Prime Minister who leaves office because of the term limit will continue to pull the strings of a puppet successor, in part because of the assumption that he will return to power as soon as the cooling-off period is over. This is why we believe it necessary to define a cooling-off period that is of significant duration length.

In light of the above, we believe that a cooling-off period of eight years would be balanced and proportionate.