Who is a Jew? Survey on Religion and State

70% of Jewish Israelis do not accept patrilineal descent and therefore do not consider those born to a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother to be Jewish. The new IDI survey reveals what Israelis really think on matters of religion and state

Introduction

The Israel Democracy Institute’s Statistical Report on Religion and State, will be published biennially and provide an overview of the latest data, trends and changes affecting the delicate balance between religion and state in Israeli society. As part of the newly inaugurated Statistical Report, a special survey was conducted by IDI’s Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research among Jewish Israelis and presented at the annual Religion and State Conference.

The survey focused specifically on questions relating both to the public’s conduct and to its attitudes on issues of religion and state (for example, working on Shabbat, consumption of kashrut services, bathing in ritual baths, conversion, and so on) and on, trust in religious institutions).

Public Trust in Religious Institutions

General Data

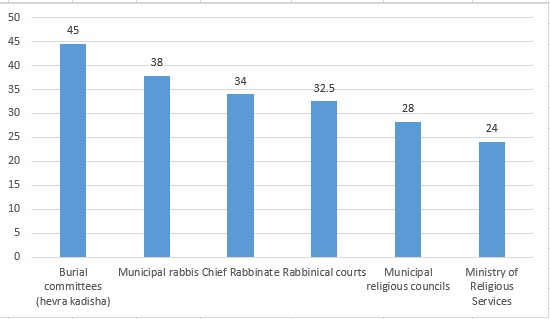

The figure below shows the extent of the Jewish public’s trust in Jewish religious institutions in Israel.

Figure 1. Trust Jewish religious institutions ("quite a lot" or "very much") (Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

The highest level of public trust was found in two municipal institutions: burial committees (45%) and municipal rabbis (38%). By contrast, trust in another municipal religious institution, religious councils, is much lower, while the Ministry of Religious Services has the lowest level of public trust of all the institutions surveyed (24%). Trust in the Chief Rabbinate and in the rabbinical courts is higher than in the municipal religious councils and the Ministry of Religious Services, but lower than in the burial committees and municipal rabbis. In general, the Jewish public’s higher levels of trust in municipal religious institutions mirror the higher levels of trust of the Israeli public in municipal government, as compared with the national government and the Knesset, as the Israeli Democracy Index has consistently found over the years.

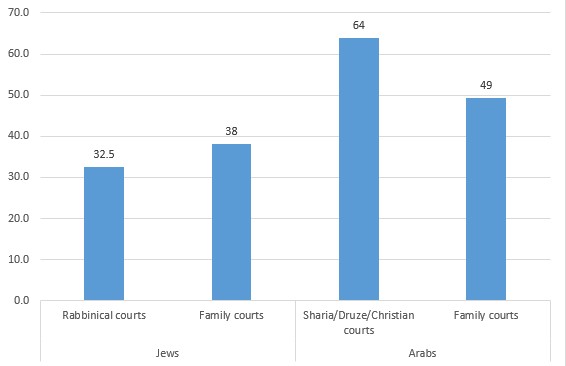

Unlike the Jewish public, the Arab public in Israel is not served by any State religious institutions other than its religious courts. In the survey, each Arab respondent was asked about their trust in the court relevant to them. Because the majority of Arabs in Israel are Muslim, most of the Arab interviewees were asked about their trust in the Sharia courts. In the figure below, Arab respondents’ trust in the Arab religious courts is shown alongside Jewish respondents’ trust in the rabbinical courts, as well as the trust in the State family courts for both groups, which are to a large extent equivalent to the various religious courts in that they all rule on issues of family law.

Figure 2. Trust) religious and civil courts dealing with family law (quite a lot or very much), by nationality (%)

The Arab public’s trust in its religious courts is much higher than the Jewish public’s trust in the rabbinical courts (twice as high), and more generally, is much higher than the Jewish public’s trust in any of the Jewish religious institutions. We can hypothesize that a major factor underlying this finding is the fact that Arabs are a minority in Israel, and as such, view their religious institutions as an arena in which they are properly represented, as opposed to other state institutions which are viewed as “Jewish.” At the same time, it is worth noting that Arab public trust is higher than Jewish public trust when it comes to family courts as well. This finding is in line with the multiyear results of the Israeli Democracy Index, which have shown a relatively high level of Arab public trust in the state court system.

In addition, it can be seen that the Jewish public has greater trust in the family courts than in the rabbinical courts, though the difference is small (38% compared with 32.5%, respectively).

Trust in Jewish Religious Institutions, by Religiosity

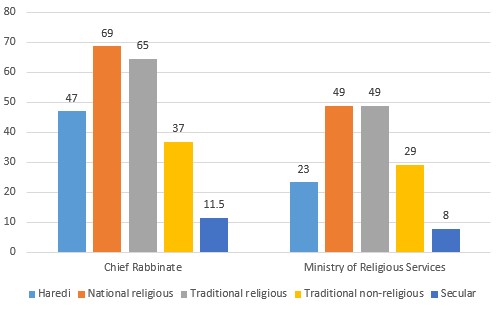

In the Jewish public, trust in religious institutions in Israel varies among the different religious groupings. The following two figures show public trust in Jewish religious institutions and in religious and civil courts, by respondents’ self-defined level of religiosity.

Figure 3. Trust) the Chief Rabbinate and the Ministry of Religious Services, by religiosity ("quite a lot" or "very much", Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

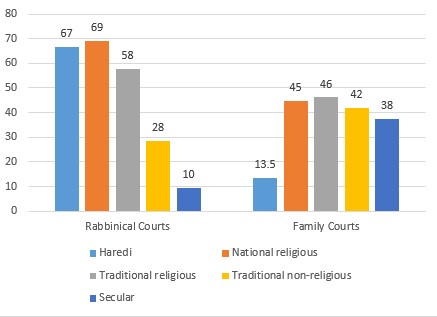

Figure 4. Trust religious and civil courts dealing with family law, by religiosity (“quite a lot or very much”, Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Overall, we see a very high level of trust in all the national religious institutions, among those identifying themselves as national religious, while the secular public displays very low levels of trust in these bodies. The traditional public is somewhere in between, with the traditional religious group being closer to the national religious public, and the traditional non-religious group closer to the secular group.

Among the Haredi public, trust levels vary strongly among the different institutions, with a relatively high degree of trust in the rabbinical courts (67%), moderate trust in the Chief Rabbinate (47%), and low trust in the Ministry of Religious Services (23%). The parallel levels of trust among the ultra-Orthodox public are 69%, 69%, and 49%, respectively. By contrast, among the secular and traditional publics there is more trust in the Chief Rabbinate than in the rabbinical courts. These findings may reflect a widespread view of the rabbinical courts as a Haredi-conservative stronghold relative to other Jewish religious institutions, and thus these courts enjoy greater support among the Haredi public than does the Chief Rabbinate, while the picture is reversed in the secular and traditional publics.

While there is a clear association between the level of trust in rabbinical courts and respondents’ religiosity, a very different picture emerges with regard to the State family courts. Haredi trust in these courts is very low (13.5%), but all the other groups have a similar degree of trust in them; indeed, the national religious and traditional religious respondents express an even higher degree of trust in the family courts than do their traditional non-religious and secular counterparts. This means that, with respect to family law at least, we are unable to paint a picture of higher secular trust in the state’s civil courts as an inverse of higher religious trust in religious courts.

The figure below shows the levels of public trust in municipal Jewish religious institutions, by religiosity.

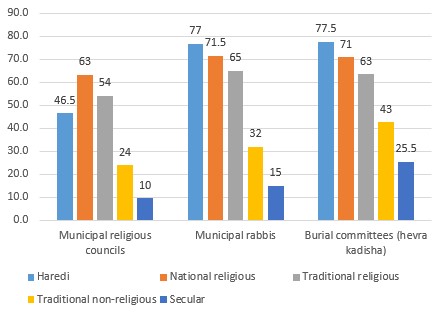

Figure 5. Trust) Municipal Jewish religious institutions, by religiosity ("quite a lot" or "very much", Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

In the Haredi public, trust in burial committees and in municipal rabbis is very high (77%), while trust in municipal religious councils is only moderate (46.5%). Among national religious respondents as well, there is stronger trust in burial committees and municipal rabbis (71%), yet trust in municipal religious councils is not much lower (63%). There is fairly low trust in all these bodies in the secular and traditional non-religious publics, with the highest level of trust recorded for burial committees (secular, 25.5%; traditional non-religious, 43%). Consequently, as we saw above, the Jewish religious institution in Israel with the highest trust rating among the Jewish public is the hevra kadisha—municipal burial committees.

Conversion and “Who is a Jew?”

Another issue examined in the survey was whether the Jewish public considers individuals to be Jewish in each of the following cases: a person born to a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother; a person who has undergone non-Orthodox conversion; and a person who underwent Orthodox conversion as part of their military service in the IDF. The survey did not ask respondents about whether the state should recognize such individuals as Jews, but rather sought their personal view of the matter.

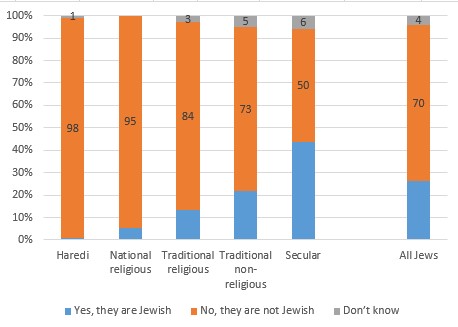

Figure 6. In your opinion, should a person born to a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother be considered Jewish? (Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

As shown in the above figure, 70% of the Jewish public do not consider someone with a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother to be Jewish, while 26% do view them as Jewish, and 4% don’t know. A breakdown of responses by religiosity reveals that the less religious the respondent, the more likely he or she is to view such an individual as Jewish. Even so, there is still a narrow majority of secular respondents who do not view someone born to a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother as Jewish (50%, versus 44%, who do consider them to be Jewish).

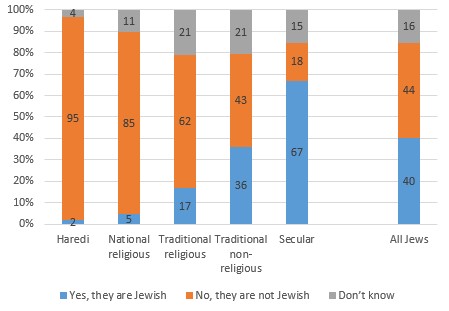

The figure below presents the opinions in the Jewish public regarding non-Orthodox conversion.

Figure 7. In your opinion, should a person who underwent non-Orthodox conversion be considered Jewish? (Jews; %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Clearly, the Jewish public is split down middle with regard to non-Orthodox conversion: 44% do not consider someone who has converted in this way to be Jewish, 40% do view them as Jewish, and 16% don’t know. On this question as well, we see a clear association with religiosity, such that the closer respondents are to the secular end of the secular-Haredi spectrum, the more likely they are to view as Jewish someone who has completed a non-Orthodox conversion process. A clear majority of the secular public consider non-Orthodox converts to be Jews (67%, versus 18% who believe they are not Jewish), while in all other groups there is a plurality who do not consider such converts to be Jewish (in the traditional non-religious public, this is the view of the largest share of respondents, though not an outright majority).

It is interesting to note that, while opinions on the case of someone with a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother were fairly clear-cut, with only 6% of respondents who “don’t know,” when it comes to non-Orthodox conversion, a much higher percentage – 16% – had no solid opinion. The share of “don’t know” responses was particularly high in the traditional public- 21% for both traditional religious and traditional non-religious respondents.

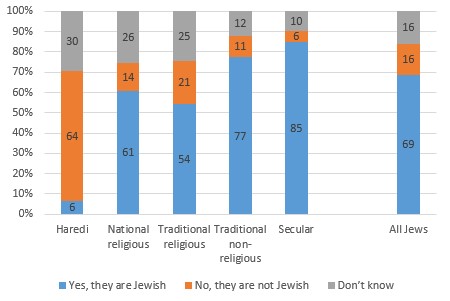

The figure below presents the views of the Jewish public regarding conversions conducted in the IDF.

Figure 8. In your opinion, should a person who underwent conversion as part of their military service in IDF be considered Jewish? (Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

When it comes to the Orthodox conversion process conducted as part of military service in the IDF, a clear majority of the Jewish public consider such converts to be Jewish, 16% who think they are not Jewish, and 16% who don’t know. With the exception of Haredim, among whom only 6% recognize IDF conversions as valid, in all other groups, a majority views these converts as Jewish. Though in general, we found an ordered scale across religiosity groups in terms of their view of different types of converts, in the case of IDF conversions the percentage of national religious respondents who recognize them, is higher than the parallel t percentage of traditional religious respondents (61% versus 54%, respectively). Presumably, this is because the system of conversion in the IDF is largely overseen by national religious rabbis, granting it greater trust among the national religious public, whereas the traditional religious public includes some who have an affiliation with the (Haredi) Shas party, whose leaders have expressed ambivalence toward IDF conversions in the past.

Regarding IDF conversions, we once again found that 16% of the Jewish public have no strong opinion, but compared with the previous question- the findings were reversed: In the case of non-Orthodox conversions, the Haredi and national religious groups had a very clear view and the share of the traditional and secular respondents who said they “don’t know” was very high, while for IDF conversions, the share of “don’t know” responses was very high in the Haredi sample (30%) and the national religious sample (26%).

It would appear that Orthodox Israelis are clear in their negative opinions on regarding non-Orthodox conversion, but when it comes to a form of Orthodox conversion that is seen as more lenient and to which some Orthodox rabbis are opposed, many of them struggle to take a firm stand one way or another. It is also possible that the reason for the large number of “don’t know” responses in the Haredi public is due to lack of familiarity with the IDF conversion program.

Ritual Baths

Ritual Bathing for Women

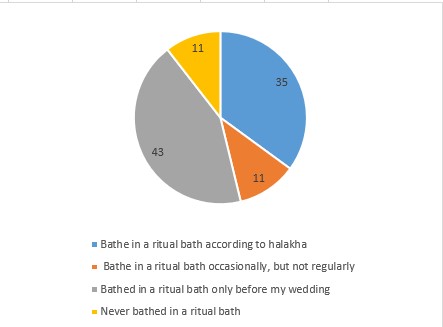

Jewish law calls for married women to bathe in a ritual bath (mikveh) on various occasions, including before marriage, each month on conclusion of their menstrual cycle, and after childbirth. Since there are married women who do not use ritual baths due to their age (post-menopausal), and women who are widowed or divorced but did engage in ritual bathing when relevant, we asked our Jewish women respondents: “Do you bathe in a ritual bath, or did you do so when this was relevant for you?” Because the Chief Rabbinate requires brides to visit a ritual bath before their wedding as part of the formal process of marriage registration in Israel, we offered response options that differentiate between women who regularly perform ritual bathing according to halakhic requirements, those who visit a ritual bath on occasion, those who did so only once before their wedding, and those who have never done so.

Figure 9. Patterns of ritual bathing behavior among Jewish women who are or have been married (%)

Burial

Religious Burial versus Civil Burial

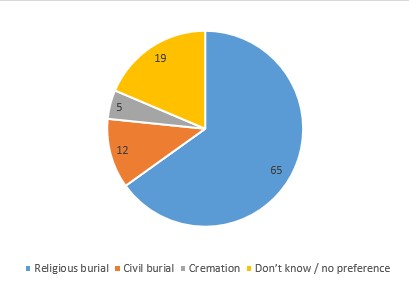

The survey also examined Jewish public preferences regarding burial. First, we asked respondents whether they would prefer a religious burial, a civil burial, or cremation. The question presented was as follows: “When the time comes, after completing the allotted 120 years of life, what type of burial would you prefer for yourself?”

Figure 10. Burial preferences in the Jewish public (%)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Two-thirds (65%) of the Jewish sample expressed a preference for religious burial, while 12% stated a clear preference for civil burial, and 5% for cremation. Notably, 19% of respondents selected the response “don’t know / no preference,” reflecting an outlook that attaches little importance to the differences between the burial options offered, or possibly- a disinclination to engage with a question about the end of life.

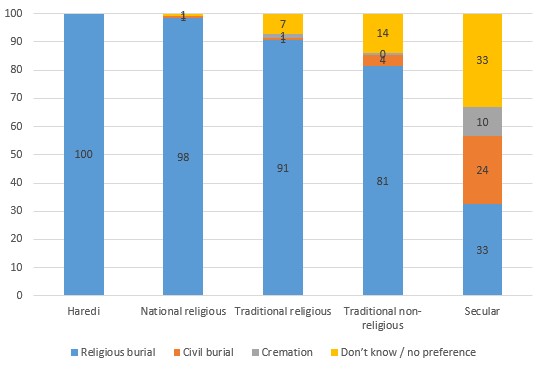

The figure below presents a breakdown of responses to this question by religiosity.

Figure 11. Burial preferences among the Jewish public, by religiosity (%)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Among the religious and traditional groups, there is a clear preference for religious burial; overwhelmingly so in the Haredi and national religious publics, and with large majorities of 91% in the traditional religious population and 81% in the traditional non-religious population. Among traditional respondents who did not express preference for religious burial, the majority did not opt for civil burial, and certainly not for cremation, but instead chose the “don’t know / no preference” response. The only group offering a diverse range of responses to this question was the secular public, of whom 33% said they prefer religious burial, 24% civil burial, 10% cremation, and a high percentage -- 33%- responded “don’t know / no preference.”

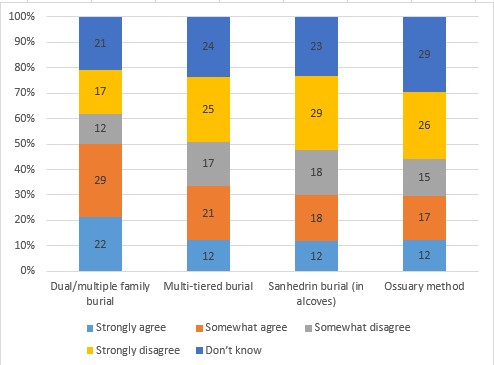

“High Density Burial”

In recent years, due to the severe and growing lack of land available for burial in Israel, the Ministry of Religious Services (with the approval of the Chief Rabbinate) has begun to encourage alternative forms of burial These include three options which are offered to the public at a much reduced cost, or even for free:

1. Dual/multiple family burial

2. Multi-story burial

3. Sanhedrin burial (in alcoves)

In addition to these options, there have been recent attempts to promote another form of burial that was used by Jews in the past—the ossuary method, which involves two stages: first, regular burial in open ground; and then, after a year, reclamation of the bones and their internment in a small casket (an ossuary). While this method is not currently being encouraged by the religious establishment, it has been adopted by several rabbis.

In the survey, we asked Jewish respondents about their attitudes to these alternative burial methods, explaining that that they are currently offered by the religious establishment (with the exception of the ossuary method), with the approval of the Chief Rabbinate, at low or zero cost.

figure 12. Level of agreement/opposition to being buried using “high density burial” methods, by method (Jews, %)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Of all the burial methods presented, the only one to which a majority of the Jewish public would agree is that of dual/multiple family burial: 51% said they would agree to this option (22% strongly agree and 29% somewhat agree), compared with 29% who would not agree to it and 21% who said they don’t know. For all the other “high density burial” methods, a similar share of respondents (around 30%) said they would agree.

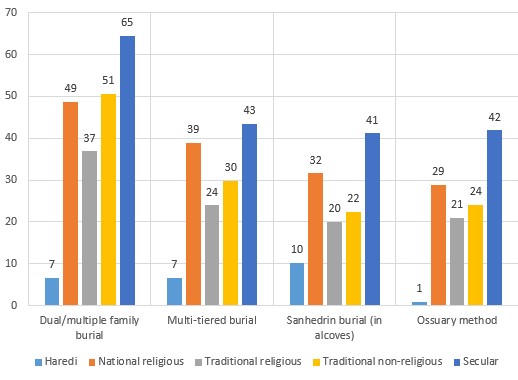

Figure 13. Agree to being buried using “high density burial” methods ("strongly agree and somewhat agree" Jews, by religiosity (%)

Source: 2022 Statistical Report on Religion and State

Among the Haredi public, there is wall-to-wall opposition to the various high density burial methods. This is in line with the public declarations against these forms of burial issued by the Haredi rabbinical leadership (particularly the Ashkenazi leadership), despite the fact that the Chief Rabbinate has approved them. This strident opposition can also be seen in in the fact that of the Haredi respondents who said they would not agree to high density burial, almost all of them selected the “strongly disagree” option, rather than “somewhat disagree.”

By contrast, the secular public is the most open to these alternative burial methods, though even here, and with the exception of dual/multiple family burial, none of the methods gained a majority of secular respondents who would agree to it, with agreement at just over 40%. In addition, between 20% and 30% of the secular group chose the option “don’t know” in response to each of the high density burial methods.

In total, we interviewed 1,230 women and men aged 18 and above: 1,016 men and women forming a representative sample of Jewish society in Israel, and 214 men and women forming a representative sample of Arab citizens of Israel. To ensure optimal representativeness of each of these samples, they were weighted according to religious self-definition (Jews and Arabs separately), age, and the relative size of the Jewish and Arab adult populations of Israel. The maximum sampling error for a sample of this size is ±2.85% for the total sample (±3.1% for the Jewish sample, and ±6.8% for the Arab sample).

The survey was conducted in August 2022 and is based on both telephone interviews and online questionnaires. Three survey companies carried out the fieldwork: The survey of the non-Haredi Jewish public comprised an online survey administered by the iPanel company; the survey of the Haredi public was carried out by Midgam Research and Consulting using telephone interviews; and the survey of the Arab public was conducted by Afkar Research and Knowledge, also by means of telephone interviews. The design of the questionnaires and survey questions were closely supervised by staff of the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research at the Israel Democracy Institute—Prof. Tamar Hermann, Dr. Or Anabi, and Yaron Kaplan. We thank them for their considerable assistance.