The Cost of Living in Israel: What do the Numbers Say?

Over the past decade average real wage of Israeli workers increased by 25% - nevertheless their purchasing power is relatively lower than the OECD average

An analysis conducted at the Israel Democracy Institute by Prof. Karnit Flug, Nadav Porat Hirsch and Roe Kenneth Portal on the cost of living reveals that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Israel has risen by 10% in the past decade – over the same period the CPI in OECD countries rose by an average of 31%. Despite the relatively sharp rise in the purchasing power of Israeli wages, that power was and remains less than the OECD average, chiefly due to the gap in labor productivity. Link to the full Hebrew analysis.

Abstract

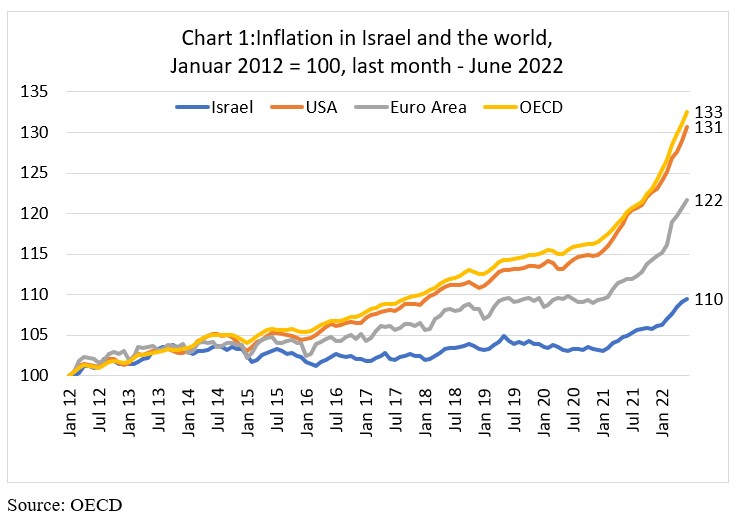

Over the last decade (January 2012 to June 2022) the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has risen by 10% (chart 1) with half of that figure, just in the past year. Indices of an average consumption basket prices, by income quintiles, show similar rises for all quintiles.

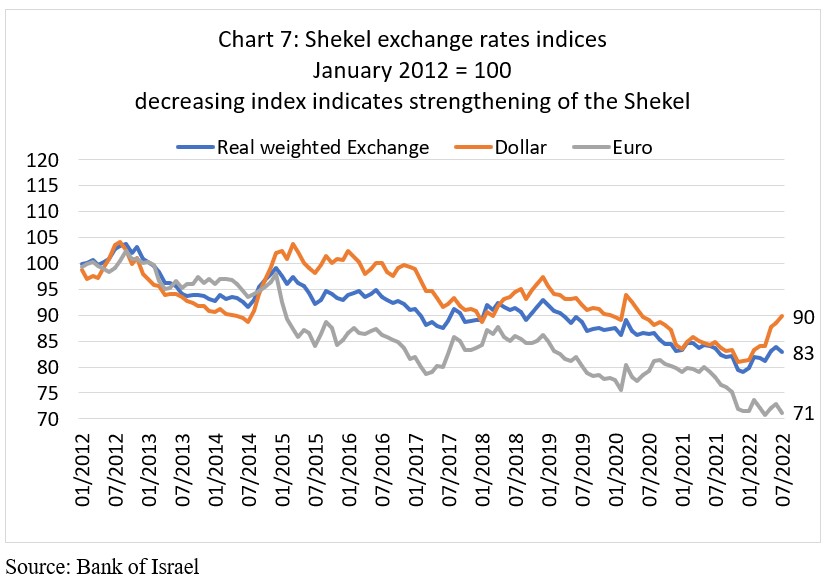

Over that same period, the CPI in the OECD countries rose by an average of 31%. A major factor of the more modest inflation rate in Israel is the strengthening of the shekel against the major currencies, which has moderated price increases of imported consumer goods.

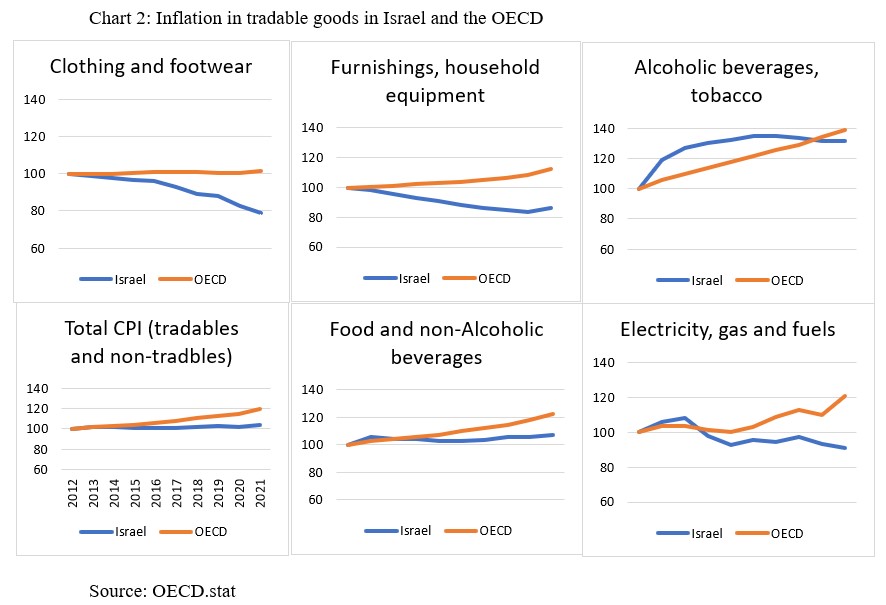

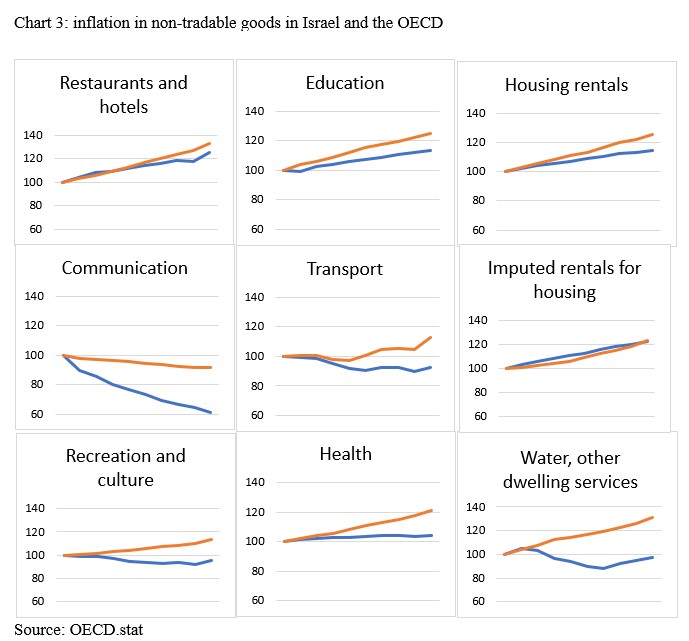

A look at the trend of the components of the CPI in Israel, over the past decade, reveals that in all categories, price increases were more moderate, or price cuts sharper, than those in the OECD countries for the same period. In general, the prices of tradable goods increased only moderately, or fell, during the decade (e.g., clothing and footwear, housewares, gas and electricity, see chart 2). Non-tradable goods and services show greater variation – there were relatively sharp increases in prices for restaurants, cafes, and hotels, as well as in education and housing; but the prices of communication services, culture and recreation, and transportation – dropped (chart 3).

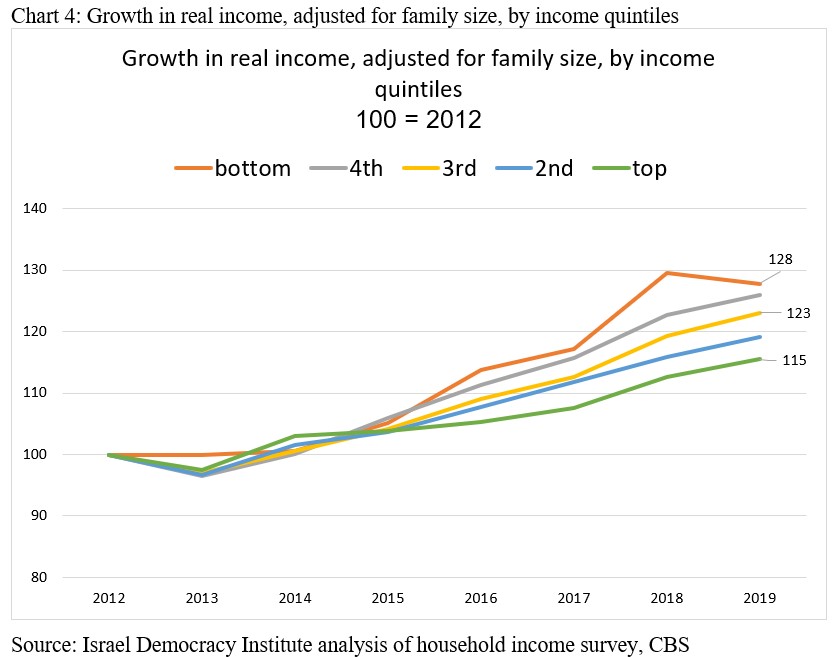

Between 2012 and 2019, the average household real net income (adjusted for family size) rose by 22%. Real household income per person increased for all five income quintiles, but especially for the lower quintiles. The better-off the quintile, the more modest was the increase in disposable household income: 28% for the lowest quintile, 26% for the middle quintile, and only 16% for the wealthiest quintile. These increases reflect a combination of the rise in employee wages and in households’ increased income from labor, chiefly as a result of the increased employment rate of women in the lower income quintiles (Chart 4).

The increase in wages and employment, that produced the growth in disposable income at all levels, more than compensated for the price increase of the average Israeli consumption basket. This increase in disposable income means a significant increase in the living standard of all income quintiles, as reflected in the continuing growth in private consumption per capita.

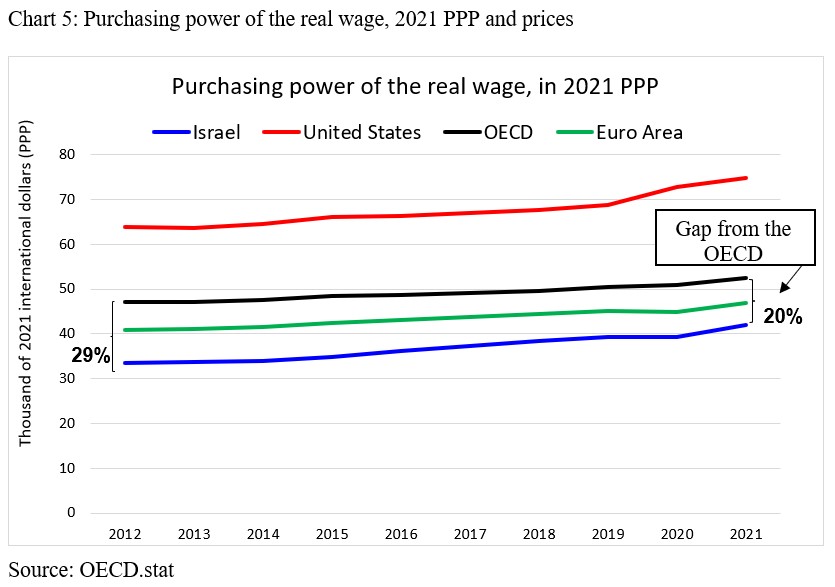

Over the last decade, the average real wage (that is, wages adjusted for inflation) of employed Israelis rose by 25%. This means that the purchasing power of Israeli workers’ salaries increased by a quarter. During those same years, the parallel figures in the United States and the Euro area were 17% and 15%, respectively. In other words, the average Israeli workers’ purchasing power increased more than that of their counterparts in Europe and the United States.

Despite the relatively sharp rise in the purchasing power of Israeli wages, that power was and remains less than the OECD average, chiefly due to the gap in labor productivity (output per worker). In 2012, the real wage of an Israeli worker was 29% lower than that in the OECD countries; it remains lower today, even though the gap between them diminished. In 2021 ,real purchasing power of Israeli wages is 20% below the OECD average, 10% below that in the Euro area, and 44% less than the figure in the United States. Relative to 2012, these gaps have contracted by between 4% and 9% (Chart 5).

It is important to focus on the difference between price inflation, which was significantly lower in Israel than the OECD average, and the absolute level of prices.

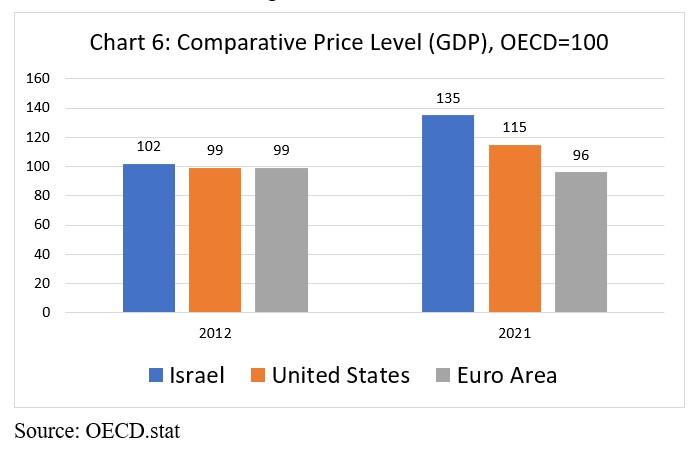

A comparison of the relative level of prices in Israel and the OECD reveals that whereas in 2012 the comparative price level (CPL) in Israel was very similar to those in the Euro area and the United States, there are large differences in 2021: prices in Israel are 40% higher than those in the Euro Area, and 17% higher than those in the United States (Chart 6).

The main explanation for the growing gap between Israel and the OECD countries, especially the Euro Area and the United States, is the strengthening of the shekel against those countries’ currencies. Between 2012 and 2021, the shekel gained 23% against the euro, 16% against the dollar, and 17% against the weighted basket (the currencies of Israel's main trade partners).

This rise of the CPL does not indicate an increase in the cost of living in Israel (which is measured directly by inflation and disposable income purchasing power) for Israelis who are paid and buy in shekels. The increase in the CPL reflects the strengthening of the shekel (or weakening of the dollar and euro against it). For tourists and foreign investors, Israel became much more expensive over the last decade. By contrast, Israelis experienced a decrease in the shekel cost of goods and services they purchase abroad or order online from foreign websites, because they are converting “strong” shekels into much weaker dollars or euros.

Even in periods when the CPL in Israel was similar to that in the OECD, before the shekel started growing stronger in 2008, some categories of goods and services were especially expensive in Israel. This applied to food and beverages and especially to milk and dairy products, personal motor vehicles, oils and fats, and restaurants, cafes, and hotels. Even though their prices did not rise in Israel more than in other countries over the past decade, their comparative price has remained high.

The relatively high prices of some consumption categories stem from the high concentration in production or import in some industries, heavy custom duties or non-tariff barriers, and long and complicated procedures for import approvals. More reasons for high prices are the Kashrut (kosher food) regulations (mainly for food), the regulatory and bureaucratic burden, and very high taxation (such as on motor vehicles). The most recent "Economic Arrangements Law" included major steps to reduce some of the tariff and nontariff barriers for imports, open the kosher food sector for competition, and reduce the regulatory and bureaucratic burden on businesses. Some of these measures have already gone into effect; other will do so in the near future. These steps can be expected to encourage competition, facilitate imports, and reduce the costs imposed by kashrut and regulations; and, ultimately, to drive down consumer prices.

Conclusion

Unlike the common perception, inflation in Israel over the past decade was more moderate than the OECD average, while the increase in household income, at all income levels, was much higher. This made possible a real increase in purchasing power and an improved standard of living. Nevertheless, prices in Israel for some consumption categories were high ten years ago and remain high today; the purchasing power of Israeli workers was and remains relatively lower than the OECD average.

Despite the significant progress, ensuring that the standard of living continues to improve requires a continuation of the current trends with regard to increase in labor productivity, which would allow wages to rise, and the integration of disadvantage people into the job market; as well as continued implementation of the reforms that aim to open up the economy for import, and to increase competition in import (by removing barriers for parallel import), in production, and in retail sales. The most recent "Economic Arrangements Law" included a series of reforms aimed at bringing down the cost of living. The "Agricultural Reform" seeks to eliminate the planning in the egg market and make it easier to import fruit and vegetables. The "Import Reform" will remove various barriers and is expected to open Israel for competition by international entities. The reform in the Kashrut supervision should reduce the attendant costs, while the reform in business licensing and regulation should reduce the excessive regulatory and bureaucratic burden and promote competition. Improved labor productivity and additional reforms are the key to further improvement in the standard of living in Israel in the next decade as well.