Farewell Elections, Hello 37th Government

The elections for the 25th Knesset assembly produced a clear result. Israel’s citizens have had their say, and the political system is now entering the next stage of the cycle: forming a new government. Over the coming days, President Herzog will consult with the representatives of the factions elected to the Knesset, and will decide whom to entrust with the task of forming a government. This will begin the process that will culminate in the swearing-in of Israel’s 37th government. What are the rules that govern this process, and what can we learn from past experience in Israel and in other countries?

Israeli president Isaac Herzog presents Likud party chairman MK Benjamin Netanyahu with the mandate to form a new Israeli government, at the President's Residence in Jerusalem on November 13, 2022. Photo by Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90

The fifth round of the recent series of elections is now behind us, and Israel’s political system is switching gear and beginning the process of forming a government.

The State of Israel belongs to the family of parliamentary democracies, in which the executive branch (the government) draws its authority from the legislative branch (the parliament), and so requires its vote of confidence. Thus, the question of who will serve as head of the executive branch—the prime minister—is not decided directly by the voters (as is the case in Presidential regimes, or as occurred during the period of “direct elections” in Israel), but depends instead on a bargaining process among the various factions elected to parliament. In democracies with “first-past-the-post” electoral systems (such as Canada or Britain), the winning party usually holds an absolute majority in parliament, and thus forming a government is a relatively simple and quick task: the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority forms the government and becomes prime minister. However, in most parliamentary democracies (including Israel), no single party holds most of the seats in parliament, so that the process of forming a government is longer and more complicated. The first stage in this process relates to the decision as to who should be charged with attempting to form the government.

In Israel, the authority to choose who will be charged with forming the government rests with the President of Israel. However, the wording of the legislation on this matter is somewhat vague: it does not provide the President with clear guidance on how to perform this important task, leaving considerable room for his or her discretion. At the same time, it is clear that the rationale for consulting with representatives of various factions is to help the President identify who has the best chances of forming a government, and charge this individual with the task of doing so. This stems from an approach which seeks to establish a government as quickly as possible, so as to reduce the time period during which the state is in a political paralysis of sorts. Other factors, such as which faction garnered the highest number of Knesset seats, or which of the candidates for prime minister was given the highest number of “recommendations” by other faction leaders, also influence the President’s decision-making, but are not binding.

It is true that in most cases, the leader of the largest faction will in any case have the best chance of forming a government1, but this is by no means the only possible outcome. In the 2009 elections, Kadima won one seat more than the Likud (28 to 27), but President Shimon Peres conferred the task of forming the government to the head of the Likud, Benjamin Netanyahu, after assessing—in the course of his consultations—that Netanyahu had the best chance of establishing a coalition.

Following the second round of the recent election series (in September 2019), President Rivlin also charged the task of forming a government to Netanyahu, despite the fact that Likud won one seat less than Blue and White. It would seem that the fact that 55 members of Knesset endorsed Netanyahu (compared with 54 for Benny Gantz, the head of Blue and White) tipped the scales. There was a similar outcome after the third round in 2020: Likud won 36 seats, three more than Blue and White, but Gantz was endorsed by 61 MKs, and Netanyahu by only 58. This was the decisive factor in Gantz being charged with the task.

Having been charged with the task of forming a government, there is no guarantee that the Knesset member assigned to the job will indeed succeed. Now, he or she must begin negotiations with potential partners in order to form a coalition that will win the confidence of the Knesset in the investiture vote. However, in fact, the Basic Law does not explicitly state that the new government must enjoy the support of an absolute majority of Knesset members.

In other words, the law allows for the establishment of a minority government, if the relative majority that will support it is larger than the minority which opposes it. (In such a situation there will inevitably be MKs who abstain from the investiture vote). However, historical experience in Israel shows that governments established after elections have almost always enjoyed the confidence of at least 61 Knesset members, and have usually enjoyed far more solid majorities.

Once the President formally assigns the leader of one of the factions with forming a government, a 28-day time limit is set for this task to be completed, but if needed, he or she may request a 14-day extension. If the nominee is unable to form a government after this extension, the ball returns to the President’s court, who may now ask another member of Knesset to try to form a government. This time, the allotted period is 28 days, with no possibility of extension. If this MK is also unsuccessful, then a group of 61 Knesset members can ask the President to give the task to a third candidate. In this case, a period of 14 days is granted, after which, if no government has been formed, early elections are announced. The Basic Law also allows the Knesset to vote (with an absolute majority of at least 61) on early elections during the coalition assembly process. This is exactly what happened at the end of last May: After Benjamin Netanyahu, assigned with the task of forming the government, failed, he did not return the mandate to the President, so as to block any attempt to transfer the mandate to another MK, and instead pushed for the Knesset’s dissolution and for repeat elections.

In sum, the law allows for three “attempts” at forming a government. However, history tells us that in almost all cases, the leader who was given the first chance to form a government succeeded in doing so.

Three exceptions should be noted in this regard:

- In 1990, after Yitzhak Shamir's government fell in a vote of no confidence, President Haim Herzog entrusted Shimon Peres with forming a new government. Coalition negotiations failed, and Peres did not succeed in presenting a new government to the Knesset. After this failure, the President charged Shamir with forming the coalition, and Shamir succeeded in establishing a narrow right-wing government.

- In 2008, after Prime Minister Ehud Olmert submitted his resignation to the President, Tzipi Livni—who was elected to replace Olmert as Kadima’s leader—was tasked with forming a new government. The coalition negotiations failed, and as a result- early elections were called.

- Following the April 2019 elections, Benjamin Netanyahu was given the first chance to form a government. He failed, and initiated the dissolution of the Knesset.

It should be noted that the two previous cases mentioned involved the formation of a government in the course of the Knesset term, rather than immediately following elections. In that sense, Netanyahu’s failure was a precedent, marking the first time that a candidate nominated by the President with the task of forming a government after elections failed to do so. However, this scenario was then repeated in the following elections in September 2019, when Netanyahu was unable to form a government, and the President passed the baton to Gantz. Gantz was also unsuccessful, and since no candidate was found who had the support of 61 MKs, new elections were called. Following the 2021 elections, Netanyahu was charged with the task of forming a government, and once again- was unable to do so. Subsequently, the President turned to Yair Lapid, who succeeded in establishing a coalition.

The period of time taken to form a government in Israel has ranged between 20 and 100 days. Compared to other countries, this is not unusually long. Belgium is the record holder: no fewer than 541 days passed between elections in June 2010 and the swearing-in of a new government in December 2011. In Germany, the previous national record was broken following the 2017 elections, when it took Angela Merkel 171 days to form her fourth government. In Sweden too, the results of the last elections (in 2018) were inconclusive, making it difficult to create a government, and four and a half months passed before agreement on a new government could be reached.

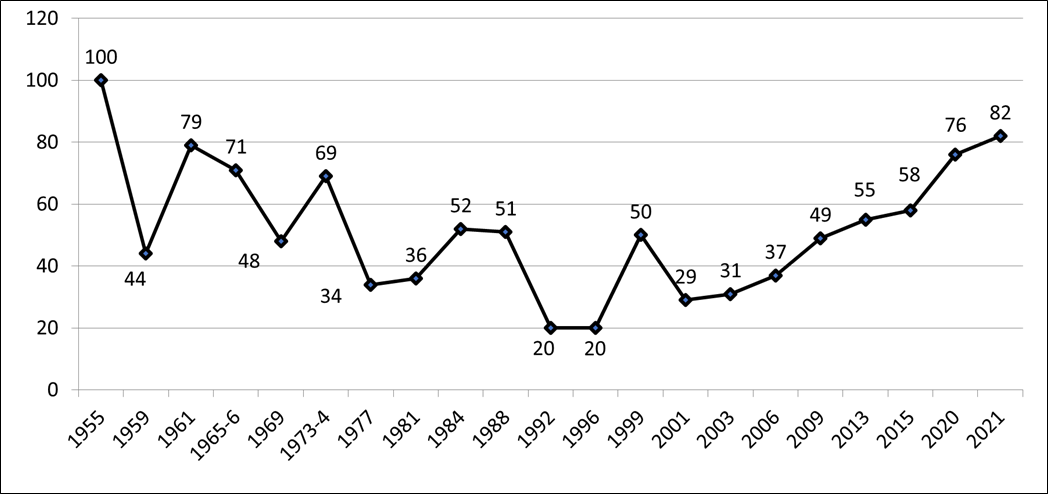

Figure 1 below shows that the process of forming a government during the first two decades of the State of Israel took longer than today, largely because in those days, the process was not limited in time. In 1955, no fewer than 100 days passed between the elections for the third Knesset and the swearing-in of the new government, and in 1961, it took 79 days from the elections for the fifth Knesset until the new government was sworn in. Subsequently, the time taken became much shorter, but since 2001, these periods have become longer again. It should be noted that the numbers given are the “gross” number of days, that is, the time that passed between election day and the swearing-in of the government. If we subtract the number of days between the elections and the time at which the President formally charged a particular candidate with the task of forming a government, then these periods are a bit shorter.

Figure. Time taken to form governments in Israel (number of days after elections held) *

*The figure includes only governments formed following elections. The number of days shown is the “gross” time period from election day to the swearing-in of a new government in the Knesset. The time taken to form the 35th government in 2020 can actually be seen as being far longer: 404 days passed from the elections held on April 9, 2019, until the government was sworn in on May 14, 2020.

Since the incoming government seeks the confidence of the Knesset, and given that no single party has ever enjoyed an overall majority of seats, all of Israel’s governments have been coalitions. The number of factions included in coalitions formed following elections has ranged over the years, from three to nine.

The record is held by the unity government formed in 1984, which included seven other factions in addition to the Alignment and Likud factions: Mafdal, Shas, Agudat Yisrael, Yamhad, Shinui, Morasha, and Ometz. Similarly, the coalition that supported the Bennett-Lapid government in 2021 comprised eight factions: Yesh Atid, Yamina, Blue and White, Yisrael Beytenu, Labor, New Hope, Meretz, and Ra’am. By comparison, the coalition formed by Yitzhak Rabin following the 1992 elections included just three factions: Labor, Meretz, and Shas.Factions may include representatives of more than one party. For example, the 34th government comprised five factions, of which two incorporated representatives of two parties each: Jewish Home (Jewish Home and National Unity) and United Torah Judaism (Agudat Yisrael and Degel Hatorah). If we count the number of parties, rather than factions, included in coalitions, then the numbers shown in Table 1 below will be even higher, and the relative size of the prime minister’s party would be even smaller, if the prime minister’s faction is made up of several parties.

Table 1 shows the number of factions in each coalition since 1992, and also presents the relative size of the prime minister’s own faction, an indication of the level of control the prime minister has over the coalition. If this percentage is low, the prime minister’s faction is to some degree constrained, and must maneuver between a greater number of coalition partners and pay a higher price to each. This gives the partners greater bargaining power and deals a significant blow to the prime minister’s ability to govern effectively and maintain a stable coalition.

Table 1. Data on the coalitions formed following elections, 1992–2015

|

Year |

Prime Minister |

Factions in the coalition |

MKs in the coalition |

Relative size of the Prime Minister's faction |

|

1992 |

Rabin |

3 |

62 |

70% |

|

1996 |

Netanyahu |

6 |

66 |

49% |

|

1999 |

Barak |

7 |

75 |

35% |

|

2001 |

Sharon |

7 |

78 |

24% |

|

2003 |

Sharon |

4 |

68 |

56% |

|

2006 |

Olmert |

4 |

67 |

43% |

|

2009 |

Netanyahu |

6 |

74 |

37% |

|

2013 |

Netanyahu |

4 |

68 |

46% |

|

2015 |

Netanyahu |

5 |

61 |

49% |

|

2020 2021 |

Netanyahu Bennett |

7 8 |

73 60 |

49% 10% |

*The numbers shown are correct as of the day on which the government was sworn in and up to a week afterwards (additional factions were sometimes added to the coalition several days after the official swearing-in of the government).

Many comparative studies on ministerial appointments in coalition governments have pointed to a principle of proportionality. According to this principle, the distribution of ministerial positions reflects the relative size of each coalition partner, such that the larger partners receive more ministerial positions than the smaller ones.

In Israel, the principle of proportionality generally predominates when it comes to coalition partners, but the ruling party does tend to gain a larger number of ministerial positions than its relative size in the coalition would imply.

Table 2. Distribution of ministers in the 34th government (sworn in in 2015)

|

Faction |

Knesset seats |

Ministers |

Ratio of seats to ministers |

|

Likud |

30 |

13 |

2.3 |

|

Kulanu |

10 |

3 |

3.3 |

|

Jewish Home |

8 |

3 |

2.7 |

|

Shas |

7 |

2 |

3.5 |

|

United Torah Judaism* |

6 |

- |

- |

|

Total |

61 |

21 |

|

* The Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox parties have historically tended not to assume ministerial positions, instead preferring other senior roles such as deputy minister or head of the Knesset Finance Committee. This policy has changed recently.

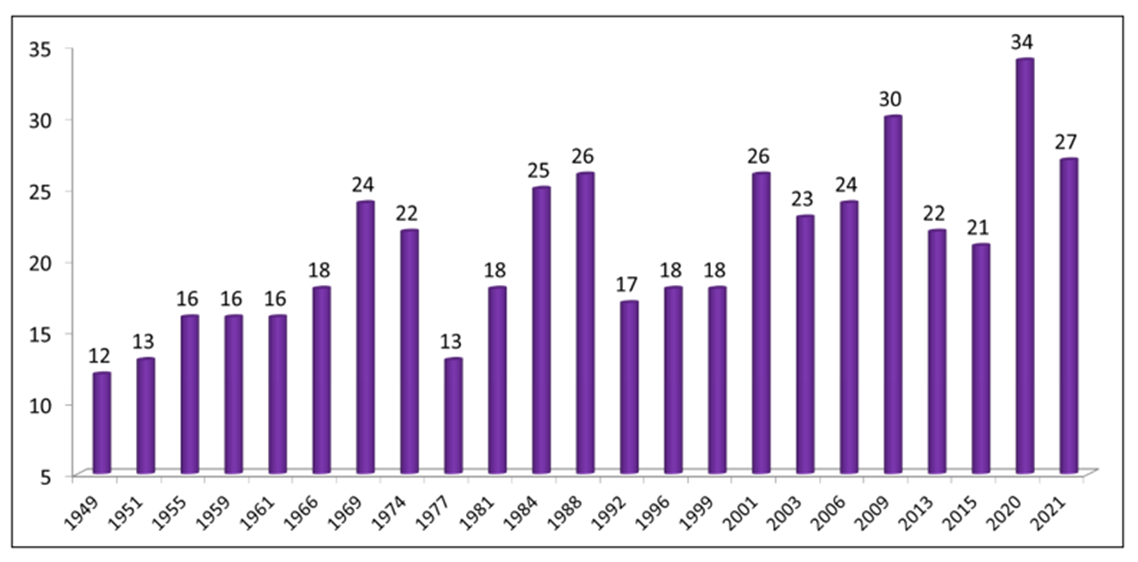

The total number of ministers serving in the government has risen considerably over the years (see Figure 2 below). The first government, sworn in in 1949, had only 12 ministers. In all the governments up to 1966, there were no more than 18 ministers. A sharp rise in the number of ministers came with the government formed following the 1969 elections, mainly due to this being a broad coalition comprising the two large electoral lists—the left-wing Alignment faction and the right-wing Gahal faction. This government, which was considered a national unity government, included 24 ministers. The national unity governments of the 1980s also had inflated ranks of ministers.

Figure 2. Number of ministers in Israeli governments formed following elections

* The figure shows the number of ministers in governments formed following elections. The values are for the number of ministers at the time the government was sworn in, up to a week after the swearing-in ceremony (on occasion, ministers were added several days after the formal swearing-in of a new government).

In 2014, an amendment was introduced to the Basic Law: The Government, limiting the number of government ministers to a maximum of 19, including the prime minister. This amendment was intended to prevent the creation of an oversized and cumbersome government and the establishment of new ministries whose real contribution is questionable, resulting in a waste of public funds. Having a large number of ministers is also detrimental to the functioning of the Knesset: The greater the number of Knesset members serving in the government, the fewer are available for the important parliamentary work of serving on committees and overseeing the executive branch.

In practice, one of the first steps taken by the 20th Knesset following its election was to suspend the limitation on the number of ministers. Thus, the government that was sworn in on May 14, 2015, numbered 21 ministers, and at one point reached 23 ministers, while the Netanyahu-Gantz government established in 2020 broke all records, and included (at the time of its formation) no fewer than 34 ministers.It should be noted that the Direct Election Law, which came into effect in 1996, included a similar restriction. Thus, the first Netanyahu government contained just 18 ministers. Three years later, when Ehud Barak was elected prime minister, the Knesset canceled this limitation, so that Barak could appoint more ministers to his government.