Financial Aggregates and New Budgetary Priorities for Israel

In May 2023, the Knesset approved a two-year state budget for 2023–2024. However, following the outbreak of the war in Gaza and the accompanying conflict in the north, the budget's composition, safety cushions, and especially the priorities it reflects are no longer suited to Israel’s economic and geopolitical realities.

Photo by Yonatan Sindel/Flash90

Abstract [A]

Background [B]

In May 2023, the Knesset approved a two-year state budget for 2023–2024. However, following the outbreak of the war in Gaza and the accompanying conflict in the north, the budget's composition, safety cushions, and especially the priorities it reflects are no longer suited to Israel’s economic and geopolitical realities.

In March 2024, a revised budget for 2024 was approved. The government sought to budget and prioritize expenses related to the war and to the associated measures needed to promote economic recovery. There is a broad consensus among economists that the revisions made to the 2024 budget are only partial, that they fail to address Israel's fundamental economic issues, and that the new budget does not reflect a relevant and up-to-date order of priorities.

In this document we highlight the failures in the priorities represented in the 2024 budget passed by the Knesset. We propose an organizing idea for changing long-term priorities, offering decision-makers and the public an analysis of what needs to be amended and corrected.

It is important to note that circumstances are changing rapidly, and thus the quantitative analysis provided here—regarding both forecasts (for growth, deficit, and so on) and policy—is based on the situation as it appeared at the end of April 2024, when this paper was concluded. However, the principles proposed remain relevant even as circumstances change.

Priorities 2023–2024 [B]

The government’s priorities in the 2023–2024 budget can be summarized in terms of the size and composition of the coalitionary budgets, which have grown larger and become much more sectorial than in the past.

Overt and accepted coalitionary funds according to breakdown by the Israel Democracy Institute (NIS)

|

Classification |

2015–2016 |

2021–2022 |

2023–2024 |

|

Accepted coalitionary funds |

2,880,000 |

5,500,412 |

811,880 |

|

Overt coalitionary funds |

2,519,550 |

1,634,848 |

10,483,980 |

|

Total |

5,399,550 |

7,135,260 |

11,295,860 |

In this study, we ranked three coalitionary agreements (2015/16, 2021/22, and 2023/24) according to the degree to which they are sectorial, on the one hand, and to the degree of professional support that was involved in formulating them, on the other. The results are clear: the coalitionary agreement for 2023–2024, is larger, less professional, and more sectorial than previous agreements. In addition, its scale uses up nearly the full range of the budget flexibility.

Long-Term Priorities [B]

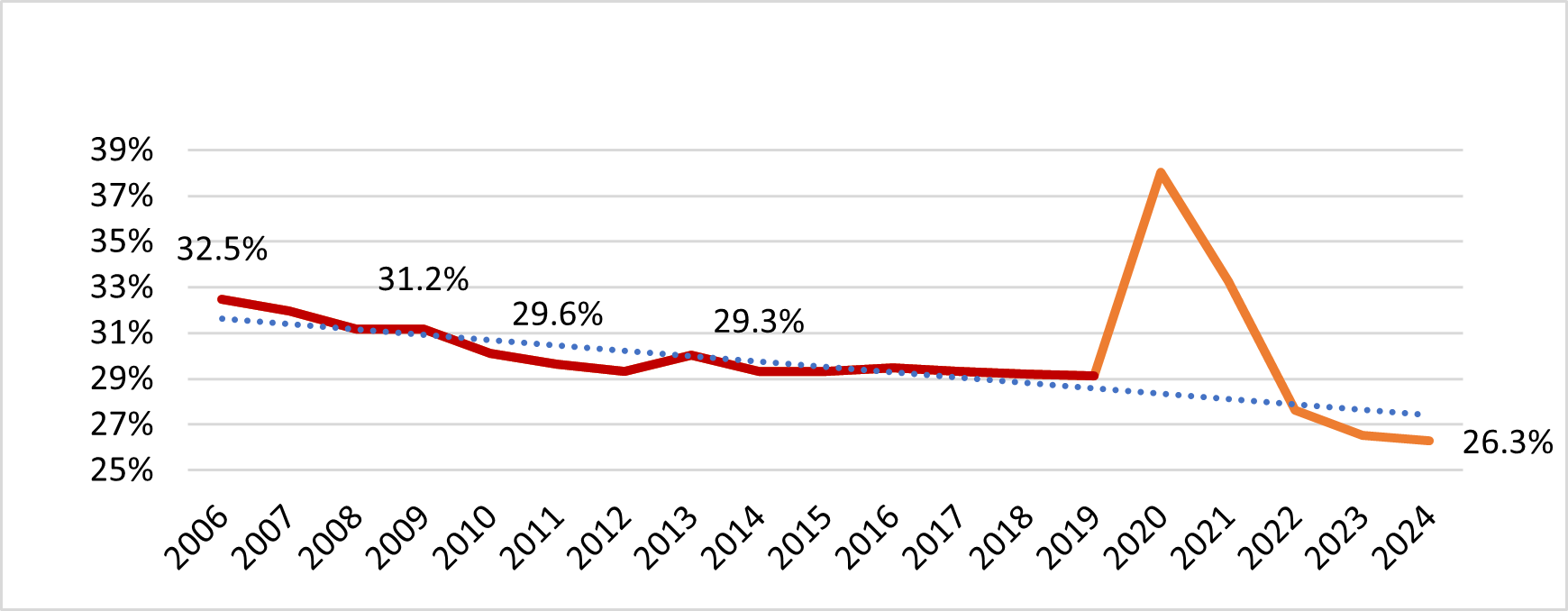

The 2023–2024 budget, as approved before the war, reflected the government’s original priorities, and continued the trend of reducing state expenditures relative to GDP, seen over the last 15–20 years. The 2024 budget reached a new low of approximately 26% of the GDP forecast for 2024. However, while savings in interest and defense expenditures have been used to reduce state expenditure and taxation, the main social budgets (which constitute approximately 40% of the state budget) have maintained their size relative to GDP over this period. This number is very low compared to most of the developed countries.

State budget as a proportion of GDP (%), 2023/24 original budget.

In fact, between 2013 and 2019, there was a period when social budgets grew by approximately 1.8 percentage points relative to GDP, even as the debt-to-GDP ratio and tax revenues as share of GDP continued to fall, and while the budgetary deficit was under control—a successful combination of a responsible economic policy with a moderate expansion of social services.

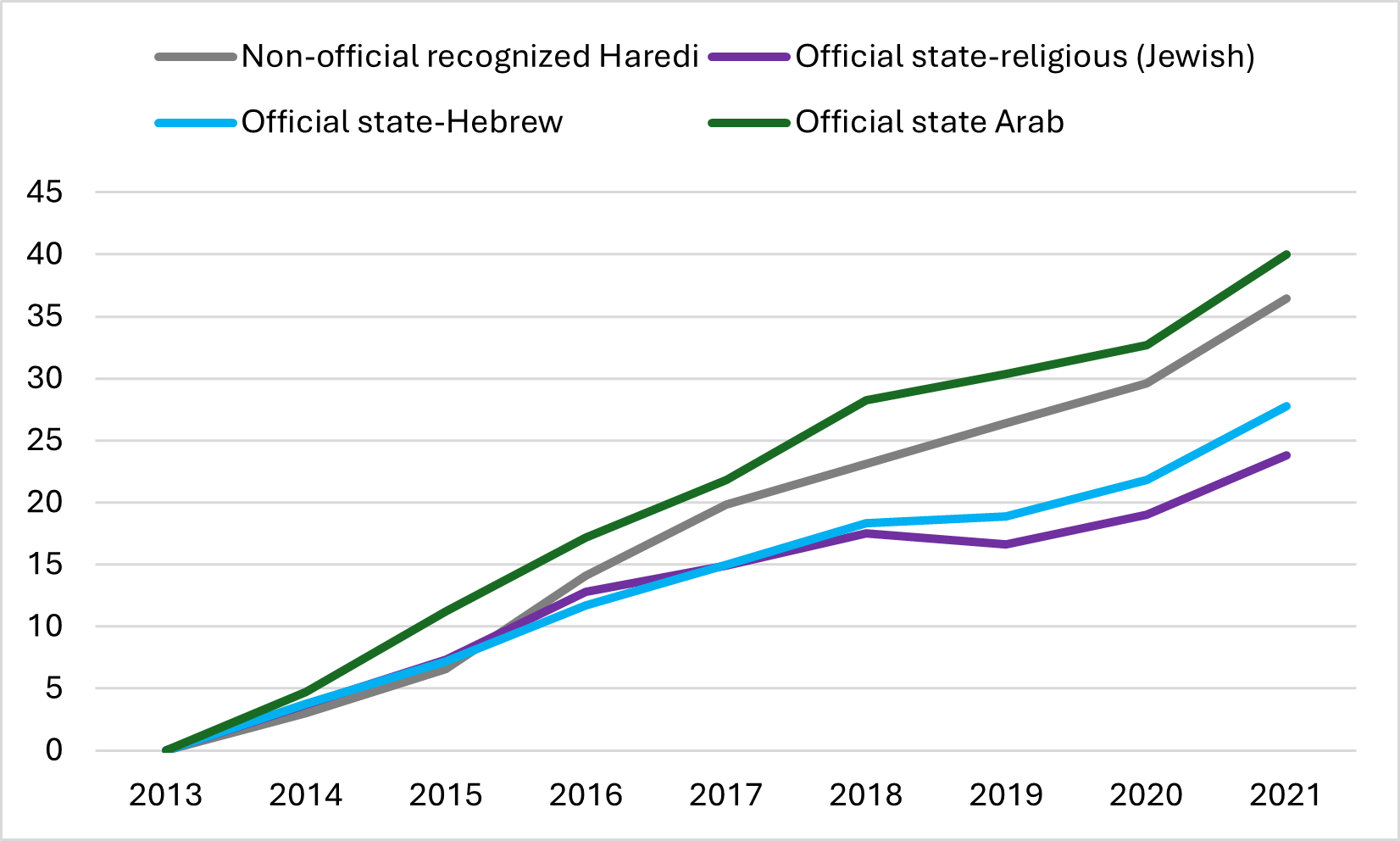

In addition, it is important to examine the internal priorities within budgets for public services, examining which areas have grown, and which have been reduced. Though the education budget has maintained its overall size relative to GDP and has even increased its share of the budget as a whole, there is a significant reduction in the share allocated to the official state-Hebrew education, relative to other educational streams.

Annual cumulative change in budget allocation per school student (%)

Looking at the changes in allocation by education stream over the last decade tells the story of changing priorities: Budgets for Haredi education (the Haredi education networks and the non-official recognized institutions) and for Arab education have increased at the highest rate, while the state-religious and state-Hebrew education streams have experienced a much more modest growth. Regarding Arab education, this change was a result of professional work aimed at reducing inequality. Indeed, a certain reduction in gaps in academic achievements has been seen. By contrast, the growth in Haredi education budget is a result of political agreements, and is not aimed at improving the quality of education provided. The moderate growth in allocations for state-religious education reflects the relatively high level of per-student funding already budgeted.

The Revised Budget for 2024 [B]

On March 13, 2024, the Knesset approved a revised budget for 2024 in response to the military and civilian expenditures incurred by the war. The budget is based on a growth forecast of 1.8%, representing zero growth per capita. It includes an additional NIS 70 billion of expenditures relative to the original budget, mainly to cover military costs and support for the economic recovery, along with a predicted deficit of 6.6%.

To partially offset this increase in expenditure, the government presented a package of fiscal cuts and tax measures totaling some NIS 17 billion. However, half of this amount will only come into effect in 2025, and at the time of writing, the package had only been partially passed into law, a fact that, by itself, casts doubt on the government’s fiscal reliability.

The extensive criticism leveled at the approved budget has a number of focuses, including the obvious need to make funds available to support the fighting, as well as covering civilian costs associated with the war, compensation for businesses, and the costs of promoting economic recovery. Beyond this, the government should have focused its budgetary cuts on pockets of economic inefficiency and identified these directly and courageously—in particular, by making cuts to the coalitionary budgets (i.e., budget items that are part of the coalition agreement, often reflecting narrow political interests), closing superfluous government ministries, and other targeted adjustments. Similarly, in order to avoid harming Israel’s strong financial status, the government should have set a deficit of no more than around 5.5% of GDP. That is, the structural deficit, excluding the military costs of the war, should have been around 3–3.5% at the very most. This course of action might have prevented the downgrading of Israel’s credit rating and its negative economic outlook, as announced by Moody’s and S&P.

New Budgetary Priorities for 2025 and Beyond [B]

Against the backdrop of the long-term trends regarding public services, and especially considering the developments since October 7, 2023, it is necessary to address the financial consequences of the war and to formulate a new prioritization, to be reflected in the state budget. Beyond the annual budget process, the government should also have a long-term strategy for the structure of the expenditure.

Goal [C]

The goal of setting a new order of priorities is to enable the Israeli economy to deal with its new and urgent challenges: funding the costs of the fighting, rebuilding the Gaza border region, and supporting businesses that have been harmed by war. This, while making the necessary adjustments to maintain the financial strength of the government and the economy, with an eye towards the “day after” the war. Additionally, the priorities need to set a clear socioeconomic horizon that will improve the standard of living of the entire population.

Long-Term Trends Affecting Fiscal Strategy [C]

Setting long-term fiscal strategy requires consideration of long-term trends, both global and local, which will affect the economy over time:

- The defense budget and its size relative to GDP. The defense budget is expected to rise as a relative share of GDP, reversing the trend of recent years.

- Demographic trends and their effect on the economy. Israel has a young population due to a high fertility rate, which puts pressure on infrastructure, housing, and education systems. A significant portion of population growth is attributable to population groups with low employment rates and low labor productivity.

- Impact of the judicial reforms and political polarization. The government has not formally canceled its program of judicial reforms, which could still negatively affect economic activity in Israel.

- Changes in the global environment. In contrast to the situation following the COVID-19 pandemic, Israel will now have to emerge from a crisis when the rest of the world is applying a policy of monetary restraint due to inflation, which can be expected to have a negative impact on the rate of recovery.

- The climate crisis. For a country like Israel, the climate crisis constitutes both a budgetary danger, in terms of expenditures necessary to deal with the effects of the crisis, and an opportunity for growth based on innovation in this field.

Overarching Principles for Fiscal Policy [C]

- Reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio [D]

The economic consensus throughout OECD states is that the target for debt-to-GDP ratio should be 60%. The policy question is how to achieve this target: Given that the debt-to-GDP ratio will be between 67% and 68% at the end of 2024, at what rate should it be returned to 60%?

- Invest in infrastructure [D]

In the coming years, the state budget and the economy will have to fund the return to an acceptable debt-to-GDP ratio, the costs of the fighting and of rebuilding, rising interest costs, higher defense costs, and the cost of maintaining and growing the country’s social services. Experience shows that when current expenses rise, investments tend to be postponed and neglected. The government must do all it can to minimize harm to investment in infrastructure, by maintaining infrastructure budgets, transferring funding to the private sector, reducing other expenditures, and finding other funding solutions.

- Increase the scale of civilian public expenditure as a percentage of GDP [D]

Comparing Israel’s civilian expenditure with the OECD average reveals a gap of around 6%, and a gap of 11.3% in civilian expenditures excluding interest. Alongside this “top-down” analysis, a “bottom-up” assessment shows that the transportation, education, and health systems have many needs, and that the country’s citizens would benefit greatly from expanding these systems. An increase in these expenditures is justified since they produce a relatively high return for the economy, and since it reflects the public preferences as shown in surveys.

Implementing the Fiscal Strategy and Aggregates for 2025 and Beyond [C]

- Debt-to-GDP ratio [D]

We propose setting a target of returning to a 60% debt-to-GDP ratio within around a decade. This represents a very gradual process. It would be appropriate to set a faster target were it not for the new priorities we propose considering the challenges described, which require a large increase in civilian expenditures.

To accelerate the reduction in debt-to-GDP ratio while minimizing the extent of the inevitable rise in taxation, the government should accelerate planned processes of privatization where they will have a positive economic impact.

- Deficit [D]

The deficit (according to the budget plan) will stand at 6.6% of GDP in 2024, and excluding a one-time expenditure of around NIS 55 billion, at just under 4%. The deficit must be reduced to allow for the reduction of the debt-to-GDP ratio to begin by 2025. The target for the deficit should be such that it enables a reduction in the tax burden as the debt-to-GDP ratio approaches the target level and could be around 1.7%.

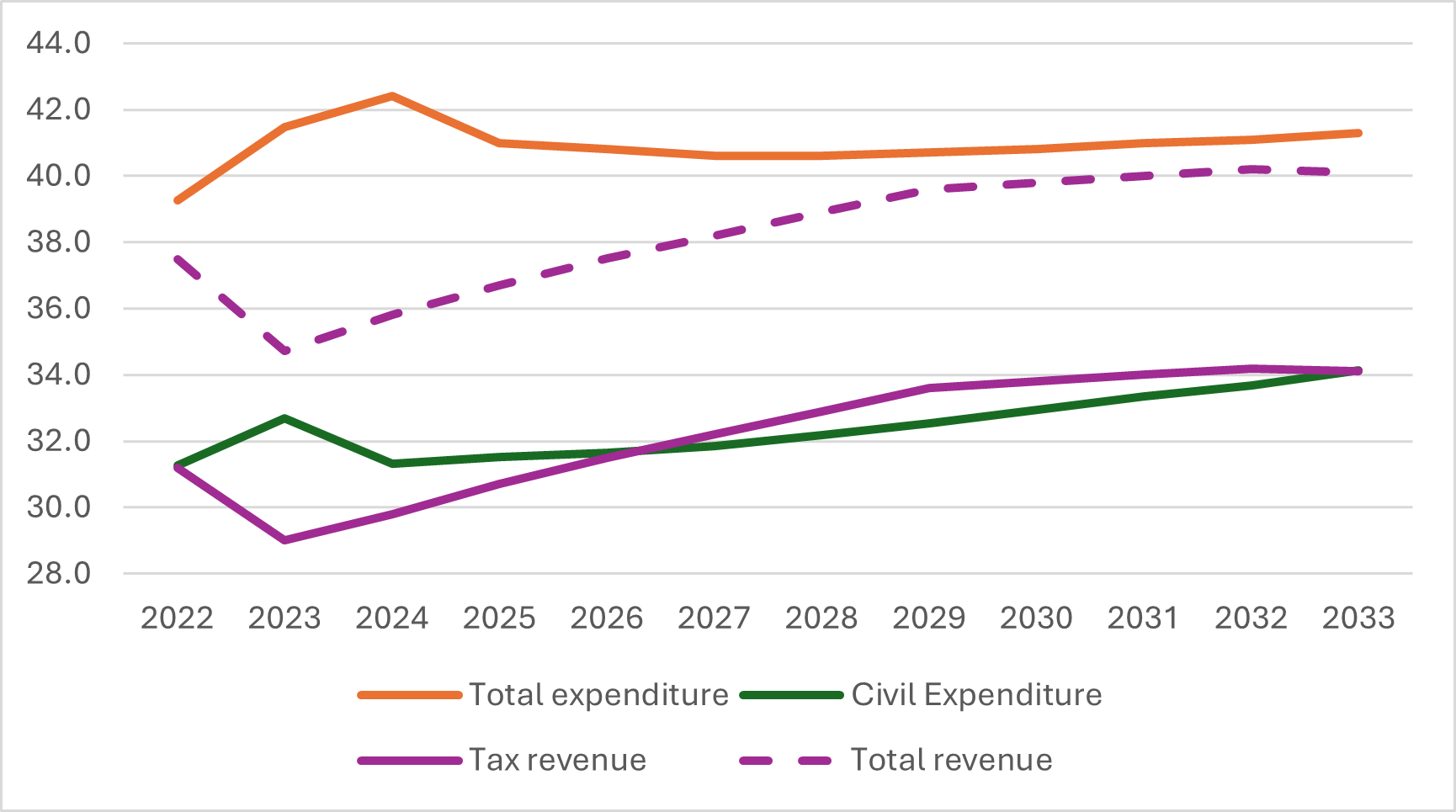

- Increased civilian public expenditure [D]

The government’s public expenditures will gradually rise, reaching 41.6% of GDP in 2033—2.5 percentage points higher than in 2022. This rise over the course of a decade will be entirely in civilian expenditures, while defense expenditures and interest payments, which will rise sharply in 2024 and 2025, will gradually decline (relative to GDP) and return to their pre-war levels.

The experience of recent years shows that improving the level of main public services, which is relatively low in Israel, is not feasible given the inequality in the tax burden born by particular population groups and the sectorial use made of budgetary tools. That is, the low level of the universal systems, education and transportation in particular, comes alongside a lack of sufficient investment in those systems. Therefore, it will be important to increase public expenditure on improving universal services. However, it is also important to continue with policies to reduce gaps and to ensure equal opportunities, particularly in education.

- Proposed expenditure aggregates [D]

State Expenditure and revenues, aggregates as a ratio of GDP (%)

The budgetary aggregates have been constructed such that the debt-to-GDP ratio will return to around 60% in ten years, the deficit level is consistent with meeting this target for reducing the debt ratio, expenditures rise gradually, and the taxation level rises in a way that does not damage the competitiveness of the economy and does not impinge on incentives for working and investing. We believe that this is the optimal outcome given the constraints in place.

- Taxation [D]

Increasing taxation is an economic necessity in order to meet the proposed targets—covering the expected increase in the defense budget, reducing the structural deficit, and reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio. It will also assist in improving public services.

Increasing taxation to fund increased public services should be done at a moderate rate on an annual basis, subject to two main principles: reducing tax benefits, which have low economic and social benefits; and maintaining competitive taxation rates for corporations and individuals, with minimum harm to incentives.

Because the goal of increased taxation is also to expand public services, it should involve expanding the tax base, and it is important that the entire public feels the benefit gained from greater taxation. Alongside this increase, there must also be significant measures to improve efficiency within the budget and in its implementation, and the expansion of public services should be broad, well explained, and clearly felt by the public.

- Investment in infrastructure [D]

There is a real concern that, considering the various fiscal challenges facing the government, adjustments to the budget will be made in the area considered to be “easiest”—infrastructure budgets. Approximately half of economic investment in infrastructure is in transport, mostly from the state budget and the remainder from local government budgets. Due to the structure of investment in different sectors, the infrastructure most likely to suffer from the impact of these fiscal challenges is public transport. It is important to maintain investment in infrastructure and especially in public transport, as the return on this investment and its contribution to public wellbeing is particularly high.

Proposal for Reform—Taking the State Budget Closer to Citizens [C]

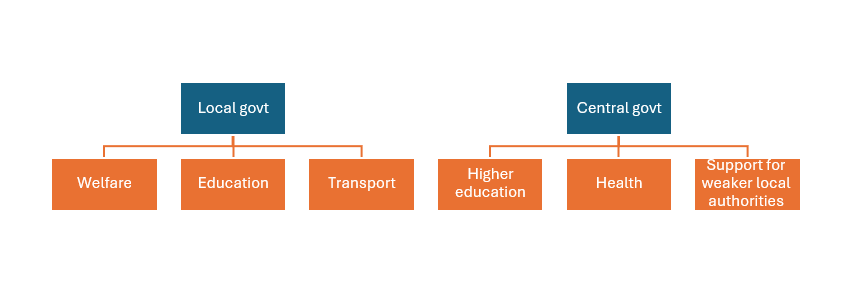

We propose that over the coming decade, budgets for education, health, transport, and higher education should be increased as a relative share of GDP. To meet all the fiscal targets listed—a return to a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 60%, a higher defense budget, and an expansion of social services—there will need to be an exceptional increase in taxation. Because public trust in central government is currently low, while trust in local government is much higher, local government should be given greater responsibility and powers for delivering services, and budget allocations should be made accordingly. We propose the following model for changing the division of labor between central and local government:

Accordingly, education and welfare budgets should be transferred to local authorities, which should be given greater leeway in deciding how to utilize them; metropolitan transport authorities should be established; and local authorities should be given greater independence, particularly the stronger authorities.