The Knesset in Numbers

Review of the 2024 Summer Session of the 25th Knesset: A Partial Return to Normal

The 25th Knesset has recently completed its summer session, which began on May 19, 2024 and concluded on Sunday July 28, 2024. This article reviews and analyzes various aspects of the Knesset’s work during this period, comparing them to the previous two full sessions of the 25th Knesset.

Photo by: Yonatan Sindel/Flash90

The 25th Knesset has recently completed its summer session, which began on May 19, 2024 and concluded on Sunday July 28, 2024. This article reviews and analyzes various aspects of the Knesset’s work during this period, comparing them to the previous two full sessions of the 25th Knesset. The summer session of 2023 and the winter session of 2023–2024, which opened immediately after the outbreak of the war. There would seem to have been something of a “return to normal” during this summer session in terms of the Knesset’s functioning, after a dramatic decline in parliamentary activity during the winter session. However, in some respects, and particularly regarding private member bills and regular parliamentary questions, the work of the Knesset has not returned to the scale it was at before the war.

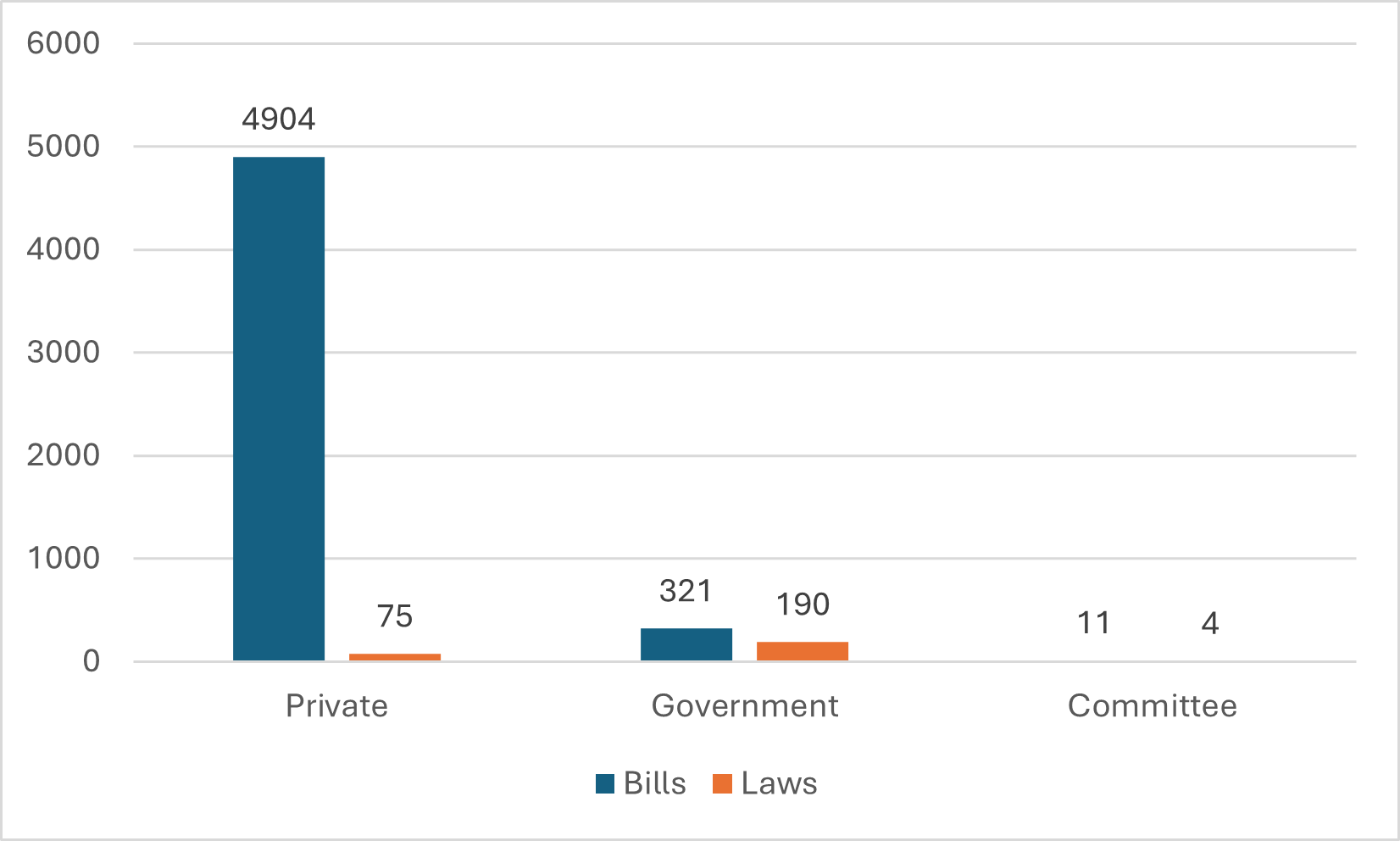

According to the Knesset’s National Legislation Database, since the current Knesset was sworn in (on November 15, 2022), a total of 5,236 bills have been submitted—4,904 private member bills, 321 government bills, and 11 bills put forward by Knesset committees. Of these, 269 bills completed the legislative process—75 private member bills, 190 government bills, and four Knesset committee bills. What stands out here is the huge discrepancy between the very large number of private member bills submitted and the small number passed into law: Of all the bills submitted, 94% were private and only 6% were government, while of all those actually passed into law, 71% were government bills and 28% were private member bills. This discrepancy stems from the fact that only a tiny proportion of private member bills submitted pass their third reading in Knesset.

This trend was also evident in the recent summer session. On the one hand, a large majority of bills submitted were private: Of 378 bills in total, 333 were private member bills (88%), 43 were government bills (11%), and two (0.5%) were bills put forward by Knesset committees. On the other hand, the majority of bills passed into law were government bills: Of the 67 bills that passed their third reading, 38 were government (57%), 28 were private (42%), and one was from a committee. It should be noted that the bills passed during the summer session were not necessarily submitted in this session; some were submitted earlier.

Figure 1: Bills submitted and laws passed by the 25th Knesset*

This large number of private member bills (even if many of them were carried over from previous Knesset sessions) marks a continuation of what has been one of the main ills of Israel’s parliament since the 1990s. The high quantity of such bills comes at the expense of their quality. It also draws the attention of all relevant parties to legislation, including Knesset members, their advisors, Knesset committees, the professional staff of the Knesset, the media, and the general public, though the vast majority of proposed bills do not progress into laws. This is at the expense of the other role of the Knesset, which is no less important: oversight of the government.

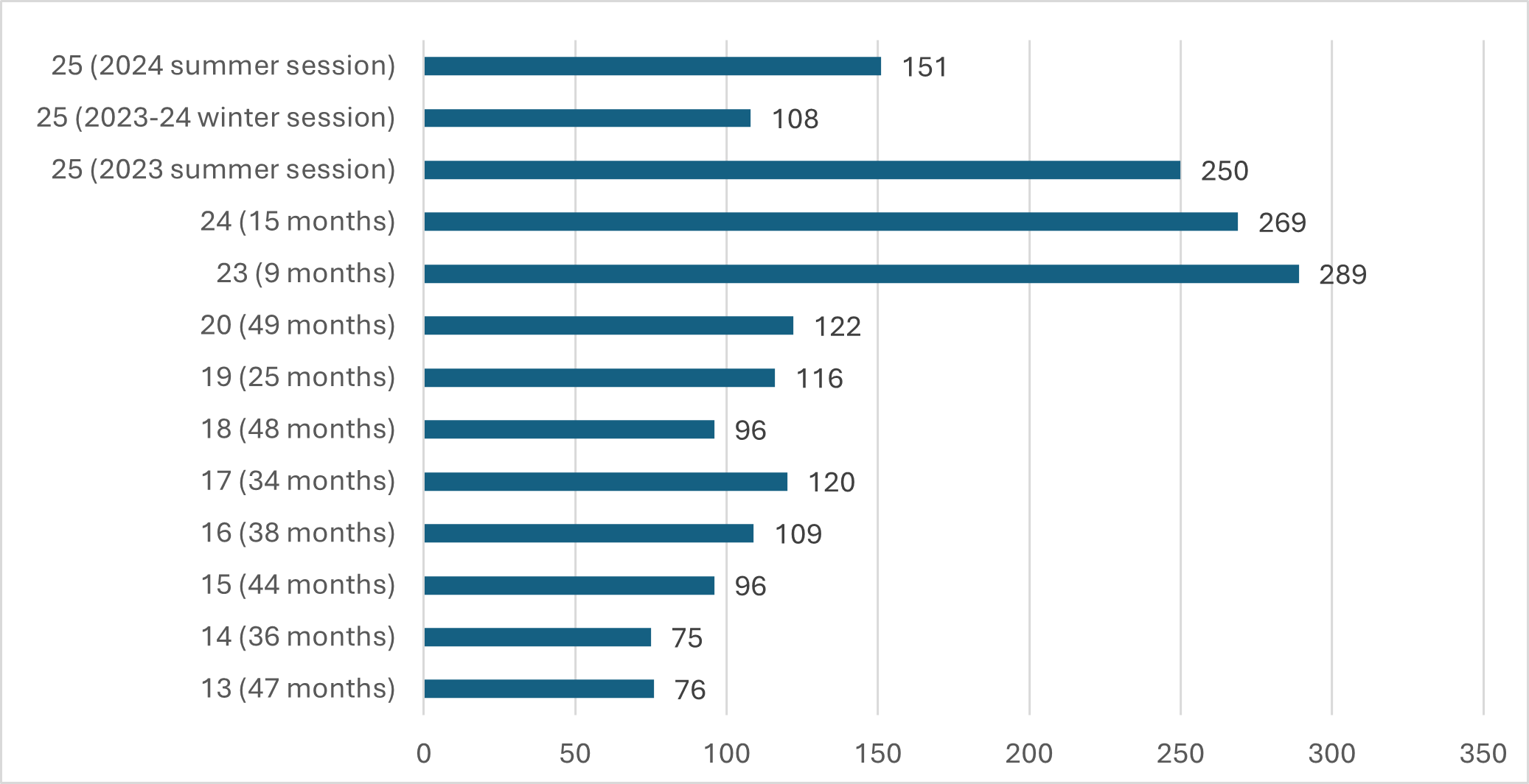

In this context, as Figure 2 shows, the quantity of private member bills (as a monthly average) submitted during the recent summer session, while still lower than in the past, is higher than that of the previous session, winter 2023–2024. Presumably, this can be attributed to the war that began on October 7: With the outbreak of war, the number of private member bills dropped sharply, seemingly because the Knesset members channeled their parliamentary work in other directions (such as work in Knesset committees or grassroots activities). Another possible reason could be that during normal times, the government uses members of the coalition to advance private member bills that it is interested in advancing (instead of using the much more complex and convoluted route of government legislation, and thus bypassing the need for an opinion from the attorney general). While during the war, the government itself put forward fewer bills that are not related to the war, and thus made less use of private member bills from coalition members (particularly during the period of the “emergency government” established at the beginning of the war, as the coalitionary agreement stated that bills not directly related to the war would only be put forward with the approval of the chair of the Likud party and the chair of the National Unity party). This decline was particularly evident during the winter session; during the recent summer session, the continuing war was in a less intensive phase, and consequently the number of private member bills rose, though it remained lower than before the war.

In any case, we view the decline in the quantity of private member bills as a desirable outcome in itself, with the potential for mitigating the harmful effects of submitting large numbers of private member bills. In particular, it allowed Knesset members to focus more of their attention on effective oversight of the government and on their relationship with the public. In this sense, the new rise in the quantity of private member bills over the summer session (whatever the reasons) perhaps signifies a return to the pattern that was common before the war.

Figure 2: Monthly average of private member bills submitted, 13th–25th Knesset assemblies

One of the well-known tools available to Knesset members—especially opposition members—is that of the parliamentary question, which allows them to direct questions to government ministers and demand information and data. There are three types of question: regular questions, to which responses are given in the Knesset plenum within 21 days; urgent questions, to which responses are given in the Knesset plenum the same week that the question was asked; and direct questions, to which responses are given directly to the Knesset member who asked them, within 21 days. Below, we focus on regular questions, which are the main form of parliamentary questions.

The trend noted above regarding the quantity of private member bills is also evident with regard to regular questions: During the 2023–2024 winter session, there was a dramatic fall in the number of questions asked and answered. The recent summer session saw a partial rebound—while the number of questions rose, it remained lower than in the past, and the percentage of questions answered remained very low, as it was during the winter session.

During the winter session, there was a very steep decline in the number of questions submitted relative to the preceding session - from a monthly average of around 73 to a monthly average of 27 questions. The recent summer session saw a rise in the use of this tool, but not a return to the pre-war numbers, with around 44 questions asked per month. Regarding responses to questions, there was a fall in response rates from 58% in the 2023 summer session to 17% in each of the last two sessions, following the beginning of the war. Similar patterns have been observed for urgent questions as well, yet to a smaller extent. It is important to note that a low quantity of questions, and in particular, a low rate of response to these questions, is particularly problematic from a democratic perspective, as it harms the ability of the Knesset to perform effective oversight of the government. Moreover, this phenomenon cannot be justified by the war. Parliamentary oversight is a central element of the Knesset’s work during normal times, but even more so during emergencies, when the government naturally takes on many additional powers and the balance of democratic power among the branches of state is tilted in its favor.

The decline in the number of regular questions submitted during the winter session was seemingly due to the significant restrictions imposed on Knesset members during the first months of the session regarding the use of the various tools available in the Knesset plenum, such as parliamentary questions and motions for the agenda. Due to the war, the Knesset Presidium (i.e., Speaker of the Knesset and their deputies) did not permit use of these tools during the first week of the winter session, and only afterward did the speaker of the Knesset announce that, in concert with the Opposition Coordinator (MK Merav Ben-Ari of Yesh Atid), it had been jointly decided to restore their use, though only regarding issues connected to the war and to an extent to be coordinated in advance. This decision was also questionable in our view, as the work of government ministries continued as usual during this period on issues unrelated to the war, such that there was no reason for parliamentary oversight of these areas to be suspended.

In practice, the decline in the number of questions submitted would seem to stem from a combination of a “chilling effect,” which deterred Knesset members from asking questions in the first place, and (opaque) decisions made by the Knesset Presidium not to approve some of the questions submitted.

In effect, the decline in the use and effectiveness of parliamentary questions since the outbreak of the war highlights some more general problems: While such questions are seen in Israel and in other democracies as a long-established and central parliamentary tool, in today’s Knesset, this tool is no longer effective. The response times to questions are long (regular questions are to be answered within 21 days); there is no requirement for the relevant ministers themselves to read out the answer in the Knesset plenum (the answer can be read by a “duty minister”); the answer given is not always to the point; and moreover, answers are often delayed or not given at all, and there is no mechanism in place to force ministers to answer questions submitted.

IDI researchers have proposed two types of solution to this issue: first, improving the questioning mechanism by including by shortening the response time for regular questions, and by imposing tighter monitoring of questions not answered and automatically referring such questions for discussion in Knesset committees; and second, by creating a more effective and media-friendly mechanism of “question time,” in which the prime minister and other ministers are required to answer questions in the Knesset in real time (a system used, for example, in the United Kingdom).[1]

Table 1: Parliamentary questions submitted during the last three sessions of the 25th Knesset

Another oversight mechanism available to Knesset members is that of tabling a motion for the agenda, designed to allow members to bring up for discussion issues they consider important. There are two kinds of motions for the agenda: regular and urgent. The difference between the two is the quota from which the motion is subtracted, and the time given to the Knesset member to argue their case for the motion to the Knesset plenum. A regular motion is taken from the quota of motions given to their Knesset faction, and the Knesset member has ten minutes to justify it, while an urgent motion is taken from the Knesset Presidium quota, and the Knesset member has three minutes to present their argument.

After a Knesset member submits a motion for the agenda, the government is entitled to present its position on the given topic, as are two additional Knesset members. Subsequently, a plenum vote is held on whether to introduce the motion to the plenum agenda, transfer it to one of the Knesset committees, or remove it from the Knesset agenda entirely.

In contrast to bills and parliamentary questions, the use of this tool has actually grown since the beginning of the war. The number of urgent motions submitted rose sharply during the winter session (from a monthly average of around 0.3 motions in the 2023 summer session to a monthly average of more than 3), and then fell (in fact, ceased entirely) during the last summer session. Meanwhile, the number of regular motions underwent a moderate rise in the winter session (from 53.5 in the 2023 summer session to 58.1 on average per month in the following winter session), and a much more significant increase during the 2024 summer session, up to a monthly average of 84.4.

This may reflect the way in which Knesset members prioritize the tools at their disposal, and the effectiveness of motions for the agenda. For example, it is possible that motions for the agenda “photograph better” and better serve Knesset members on social media. In addition, unlike parliamentary questions, the use of motions for the agenda is not slanted toward a particular political camp, and Knesset members from both the opposition and the coalition utilize this tool extensively.

Table 2: Motions for the agenda submitted during the last three sessions of the 25th Knesset

In Israel’s parliamentary regime, the government operates on the basis of the confidence of the Knesset. The most obvious expression of this principle, found in every parliamentary democracy, is the option for the parliament to pass a vote of no confidence in the government. This is parliament’s strongest oversight tool, with a far-reaching impact—a change of government. Israel uses a system of “full” constructive no confidence, meaning that a no-confidence motion can only be passed if: (a) at least 61 Knesset members vote in favor; and (b) the motion includes a proposal for an alternative government, which is then appointed as soon as the no-confidence motion is passed. This is a system that makes it very difficult to bring down or replace a government. However, even if they have no chance of passing, no-confidence motions are brought forth by opposition factions as an act of resistance to the serving government, or as an expression of harsh criticism against it.

The winter session following the outbreak of the war saw a clear decline in the number of no-confidence motions submitted in the Knesset. While the recent summer session brought a rise in these motions, the use of this tool remained more restricted than during the period before the war. Thus, during the 2023 summer session, 26 no-confidence motions were brought forward, an average of 8.6 per month; in the winter session, there were 9 motions, at a monthly average of 1.6; and during the recent summer session, there were 19 motions, for an average of 7.6 per month. The difference between the 2023 and 2024 summer sessions may stem from the fact that the National Unity faction, which was in opposition in 2023, was still part of the coalition during the first three weeks of the 2024 summer session.

The Knesset Ethics Committee contains four members, two from the coalition and two from the opposition, with one of the coalition members serving as chair. Decisions are made with a majority of at least three members. The Committee is entrusted with providing ethical guidelines to Knesset members, authorizing Knesset members’ travel abroad if not funded by the Knesset, and responding to ethical questions as and when they arise. It also has the power to hold disciplinary proceedings against Knesset members who contravene the ethical rules that appear in the Knesset Regulations or who are absent more than is legally permitted, and apply sanctions against them under the terms of section 13(d) of the Knesset Members (Immunity, Rights and Duties( Law, 1951.

During the 2023 summer session, the Ethics Committee passed five decisions: two were guidelines to Knesset members, and three were decisions on complaints submitted against four Knesset members (two were even disciplined—the government minister May Golan of the Likud, and the Knesset member Ofer Cassif of Hadash-Ta’al). Unlike other aspects of parliamentary activity, this area was not negatively affected by the war. During the winter session, the Committee made 12 decisions—four guidelines, and eight decisions on complaints submitted against Knesset members (of these, seven were disciplined: Ofer Cassif, Aida Touma-Suleiman, Ahmad Tibi, and Ayman Odeh of Hadash-Ta’al; Nissim Vaturi and Tally Gotliv of the Likud; and Iman Khatib-Yassin of Ra’am). A large proportion of the ethics committee’s decisions dealt with issues related to the war: for example, a decision regarding volunteering and fundraising activities in connection with the war, and complaints about statements made by Knesset members in the context of the war. By contrast, during the recent summer session, the Ethics Committee did not make a single decision—neither on ethical guidelines, nor on complaints against Knesset members.

The three sessions of the 25th Knesset examined in this review—the 2024 summer session, the previous winter session, and the 2023 summer session—were conducted in different circumstances. While the 2023 summer session was held under the shadow of discussions about the government’s judicial reforms, the winter session and the 2024 summer session were held under the shadow of the war in Gaza. It would seem that the most recent summer session saw a trend of returning to normal regarding the work of the Knesset, after a dramatic decline in parliamentary activity during the winter session.

[1] For more details, see: Chen Friedberg, How to Improve the Knesset as a Legislative and Oversight Body: Key Recommendations, Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute, 2018.