Women and Civil Society in Israel

Over 50 registered women's organizations exist in Israel, most working to solve problems that women face—such as daycare fees, assistance to single mothers, etc. with just a few focusing on more general agendas—such as defense, social welfare, etc. This article, originally published in Hebrew in IDI's online journal Parliament, surveys the unique characteristics of women's organizations and how they affect productivity.

Introduction: Women's Organizations on Behalf of Women

"Before the war, everything you men did, we suffered in silence and dignity because you wouldn't let us make a sound. Not a peep. God, we hated you for that! . . . And if, now in turn, you want to shut up and listen to our good advice, we'll straighten everything out for you!" (from Lysistrata by Aristophanes)

In Israel, there are over 50 registered women's organizations, the majority of which are devoted to providing solutions—such as preschool daycare, assistance to single mothers, and legal counseling—to the problems women face. Other organizations have a more general agenda focused on issues such as peace, security, and social welfare.

There are at least two explanations for the fact that women organize themselves into strictly female organizations:

- Women do things differently. Politics today is male-dominated, and to generate change women need to create an alternative—one that draws on a woman's view of reality.

- Since women fail to become assimilated into politics in general, they need to create their own realms of activity.

Political ideas and social change provided the backdrop for the establishment of Israeli women's organizations:

- The feminist movement and feminist thinking: The movement, together with the ideology, provided the social and conceptual framework for the organizations' creation. Changes in the social structure led to greater political involvement by women and opened the door to their participation in civil society. Backed by ideology, they were able to make the transition from private life to public life, and views about suitable roles for women changed as a result. Feminism promotes the idea that women can manage politics differently than men can. There is therefore an essential advantage to activities that involve women only, since they offer an ideological and effective alternative based on a different point of view.

- Socioeconomic changes: Rising women's participation in the workforce, higher educational attainments by women, and changes in traditional family role divisions empowered women and encouraged them to aspire to achieving equal rights in every area of life.

- New politics: The 1960s ushered in a significant rise in the standard of living. The struggle for survival gave way to a desire for quality of life, and traditional politics, concerned mainly with economics and defense, was replaced by identity politics, based in part on gender and ethnicity. The issues on the new political agenda are minority rights, gender equality, peace, and environmental quality. Civil society blossomed and developed alongside the new politics, and women's organizations were an integral part of these social trends.

Criteria for Categorizing Women's Organizations in Israel

Content:

- Organizations that function on behalf of women by providing services in areas of personal concern to women (such as sexual harassment and family violence) and by working for equal rights.

- Organizations that promote the general interests of women in politics, society, and the economy (peace organizations, for example).

The distinction between the areas of activity is not absolute, since equality is the concern of every sector in society, and the distress of single mothers is only one aspect of an economic policy that affects the character of the entire society.

Socioeconomic characteristics of families:

Upper middle class status: Primarily protest organizations and movements.

Low economic status: Local organizational efforts prompted by economic distress.

Form:

Established organizations and protest movements (the latter being either loosely established or not established to any degree).

Scale:

The range of the organization's activities at the local, national, and international levels:

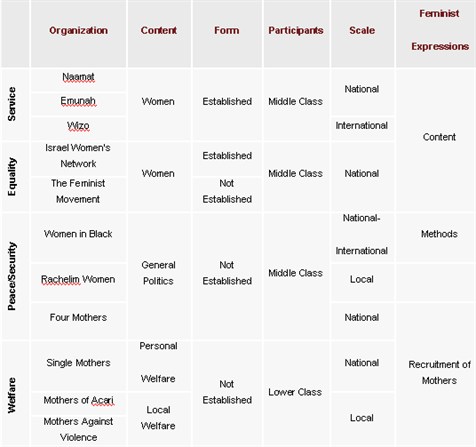

Table 1: Categorization of the Organizations Discussed in this Article

Service Provision

Women's movements have been active in Israeli society, alongside the country's institutions, since well before the state's establishment. Naamat and Wizo date back to the 1920s, and Emunah, founded in the 1930s, took on the task of representing the interests of female Haluzot ("pioneers") and laborers. Today, all three movements provide services that address women's needs (such as preschool daycare) and work to promote the status of women in the public sphere.

According to Herzog (1999), the activities of these organizations, voluntary in nature, retain the stereotypes of women's involvement in community affairs and offer no opportunity for members to build political strength.

Equality

Organizations with a clearly political agenda: The Israel Women's Network, established in 1984, lobbies for promoting the status of women through education, legislation, and the courts; The Feminist Movement, established in the early 1970s, challenged conventional thinking and proposed reexamining society from a feminist point of view. The movement devoted its efforts to forming feminist consciousness-raising groups and organizing protests.

Protest Movements Related to Peace and Security

In addition to the established and less-established organizations concerned primarily with civil society, Israel has given rise to political protest movements that address issues on the national agenda. Participation in these movements is less strictly organized, for the most part, and they take shape according to the urgency of the issues at hand. Defense-related issues are especially salient in Israel, and they draw civilian responses on both the left and right ends of the political spectrum. Although issues of peace and defense raise questions and demands that affect all of Israeli society, the protest movements that have formed surrounding these issues consist entirely of women.

The connection between women's movements and peace movements is not unique to Israel. Two of the better known examples are the anti-Apartheid Black Sash movement in South Africa and the Greenham Common Women in Britain, which protests the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

There are more than ten movements in Israel that combine "women" and "peace." Public opinion surveys, it is worth noting, show no differences between the views of Israeli men and women on issues related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Herman, 2002). These movements include Women in Black, MachsomWatch (Checkpoint Watch), Shuvi (Come Home), and the Women's Peace Coalition.

The Women In Black movement, one of the oldest of this type, began operating in 1988 by organizing ongoing protest demonstrations at set times and intersections. The participants dress entirely in black and carry banners with the message, "End the Occupation." Women in Black demonstrations take place throughout the country, and in the 1990s, the movement spread beyond Israel and began to conduct its protests internationally as well.

Although Women in Black never defined itself as a feminist group, it has acquired the characteristic signs of a women's movement:

- Organizational structure: The structure is characterized by typically feminist features such as agreement, decentralization, non-hierarchical organization, and autonomy (giving each group of demonstrators the leeway to create its own rules).

- Methods:

- The organization employs methods that are consistent with women's needs. The demonstrations are planned so that any woman can contribute to the struggle, without having to travel to downtown locations or leave their children at home, for example.

- Women in Black make use of their bodies to deliver a message, a particularly feminist approach that has been dubbed "the protesting body" (Sasson-Levi and Rappaport, 2002).

- Message: The movement's somewhat amorphous message allows a variety of women to identify with it and interpret it in ways that best suit their own points of view. In this way, the movement has managed to become ideologically multi-faceted (and "inclusion" is considered a women's trait). In addition, its women's message of peace calls on both Israelis and Palestinians to create a society in which education, welfare, and agreement rather than conflict are top priorities (Svirsky, 2003).

On the other side of the political map is the Rachelim Women movement. Following a terrorist incident at the site, it organized regular protests, in memory of the victims, at the Tapuach intersection in Samaria and later established the nearby Rachelim settlement. The women participating in these protests opt for a quiet approach and emotional appeals (as opposed to male appeals to reason), in combination with messages of motherly love and concern for children (Elor, 1993).

Motherhood and Defense

Women's movements that address defense issues are stifled somewhat by the dominantly male discourse in this area, and one way they attempt to overcome the obstacle is to highlight their identity as mothers. Four Mothers, founded in 1997 to demand an I.D.F. withdrawal from Lebanon, typified use of the "mother" image—in this case the mother who sends her sons off to the army and worries about their safety. The movement then evolved into a focal point for protesting defense policy in general. One of its founders explains: "We knew it was the scream of the womb that would be heard. If we didn't speak in the name of mothers, we'd melt like marshmallows" (Shavit, 2006). Similar movements are active in other parts of the world; one example is the Russian Mothers of Soldiers Committee that struggled for a military withdrawal from Chechnya.

Protests over Welfare Conditions

Most of the women active in welfare-oriented organizations come from the lower end of the socioeconomic scale. Israeli's neo-liberal economic policies and scaled-back government involvement in the provision of welfare services have harmed the country's vulnerable populations. In response, grassroots organizations have launched struggles to combat these policies and approaches, whose primary victims are women. Economic distress and a lack of government assistance have prevented many women from fulfilling their usual family roles. Organizational efforts, therefore, are prompted primarily by existential distress, and the fact that the participants are women is a natural consequence of their role as mothers concerned with the welfare of their children.

Examples of these movements worldwide include Mothers of Acari, founded in Rio de Janeiro in 1990, which led a successful struggle for economic, social, and political rights, resulting in a significant change in public thinking about the residents of a poor neighborhood. The Acari neighborhood became a symbol of resistance to governmental discrimination. The Women Against Violence movement in New York was established in 1991 to help eradicate neighborhood violence and make the immediate environment a safer place for their families.

Examples of these movements in Israel include the Single Mothers' Movement, led by Vicki Knafo, who, with no resources and no access to centers of power, drew considerable media attention by connecting with key symbols in Israeli culture. For example, her decision to walk the distance from Mitzpeh Ramon to Jerusalem was inspired by military treks, and the image she portrayed as a mother was consistent with the country's overall cultural conception of a woman's role (Gal Ezer, 2006).

Summary

Women's movements in Israel are growing in number, a fact that parallels the general trend of an expanding civil society in the country and worldwide. A survey of the unique characteristics of women's organizations raises the following question: Do women's organizations benefit women's interests and provide society with an alternative to the existing male point of view, or, on the other hand, do women-only organizations prevent women from entering key circles of influence?

Sources

Aristophanes. Lysistrata. http://www.users.bigpond.net.au/soloword/Lysistrata.htm.

Elor, Tamar, 1993. "You Can't See Iceland from Shilo: The Rachelim Incident" (Hebrew). Alpayim, 7:59-81.

Gal Ezer, Miri (2006). "Vicki Knafo: Body, Habitus, Gender, Patriotism, and Protest" (Hebrew).

Gadish, 10:290-292.

Herman, Tamar (2002). "The Israeli Peace Movement: The Current Situation and Chances of Success" (Hebrew). http://www.shatil.org.il/data/tamar_herman_research.doc.

Herzog, Hanna (1999). Gendering Politics: Women in Israel. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Kampf, Ronit (1996). "The Search for Chinks in the Wall: The Interaction between Women's Protest

Movements and the Israeli Media" (Hebrew) Patuach, 3:4-26.

Lemish, Dafna and Inbal Barzel (2000). "Four Mothers: the Womb in the Public Sphere." European

Journal of Communication, 15(2): 147-169.

Lind, Amy and Martha Farmelo (1996). "Gender and Urban Social Movements, Women's Community Responses to Restructuring and Urban Poverty," UNRISD, Discussion Paper No. 76.

Sasson Levi, Orna and Tamar Rappaport (2002). "Body, Ideology, and Gender in Social Movements" (Hebrew). Megamot, 4:513-489.

Shavit, Ari (2006). "This Time its Different, This Time There's no Choice" (Hebrew). Haaretz, July 28, 2006.

Svirsky, Gila (2003). "Local Coalitions, Global Partners: The Women's Peace Movement in Israel and Beyond." Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 29(2): 543-550.

Naomi Himeyn Raisch is a Research Assistant at IDI and an M.A. student at the Department of Political Science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.