Coalition Building in Israel: A Guide for the Perplexed

In this article, specially written for the IDI website, Dr. Ofer Kenig explains the basic principles of the process of coalition building that will culminate in the investiture of the 33rd government of the State of Israel.

Introduction

Approximately one week after the 19th Knesset elections, after receiving the official election results, Israeli President Shimon Peres invited representatives of each of the elected parties to meet with him and recommend the party leader who should be tasked with the job of forming the next government. After hearing their responses, President Peres entrusted Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with the task, beginning the important process that will culminate with the investiture of of the 33rd government of the State of Israel. How does this process work?

Who Forms the Government?

In Israel, the President appoints a member of Knesset to try to form a government. Before deciding, the President consults with representatives of each of the parties that were elected to the Knesset. While the President usually assigns this task to the leader of the largest party, it is not mandatory. Israeli law gives the President broad discretion in this decision. Indeed, in the 2009 elections, Kadima won one more seat than the Likud (28 versus 27), which led Tzipi Livni, who then headed the party, to demand that the President entrust her with the job of building the coalition. After consulting the representatives of the Knesset parties, however, the President realized that Netanyahu had broader support than Livni and was more likely to succeed in putting together a coalition. He therefore assigned the task to Benjamin Netanyahu. The results of the current 2013 elections left little room for doubt: Most of the parties recommended that President Peres assign the task of government formation to Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of the largest party in the 19th Knesset, who indeed received the assignment.

In some other parliamentary democracies, a different model is used. The authority to appoint a member of parliament to form the government is not entrusted to the Head of State; rather, according to law, the head of the largest party automatically receives the first chance to try to form a government. For example, the Greek Constitution states that the right to form a government is first granted to the head of the largest party. If the head of the largest party fails to achieve this goal, the head of the second largest party is tasked with assembling the government, and so on. In other countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium the process is slightly different. In those countries, the monarch is seen as a non-partisan figure who should not be involved in day-to-day politics. Therefore, the monarch is not the one who determines the person who has the greatest chance of forming a government; rather, he appoints a symbolic figure—usually a former politician—with extensive experience and prestige, who still has no direct bearing on politics. Known as an informateur, this figure consults with the leaders of the country's political parties in order to determine who has the greatest chance of forming the government. After identifying the person with the greatest chance of success, the informateur makes a recommendation to the monarch, who formally entrusts that person with the job of forming the government.

How Much Time Does the Process Take? Is there a Deadline?

Once Benjamin Netanyahu is entrusted with the job of government formation, he will have 28 days to complete the task. At the end of that period, if necessary, he could ask for an extension of up to 14 days. When that extension period ends, if Netanyahu has still not been able to form a government, the President may assign the task to a different member of Knesset. This time, the task must be completed within 28 days, with no possibility of an extension.

Historically, the length of time taken to form a government in Israel has ranged from 20 to 100 days (see Figure 1). This is within the norms of time that it takes to form a government in other parliamentary democracies, where it has sometimes taken even longer. Belgium is actually the record holder in this area: no less than 541 days elapsed between the elections in June 2010 and the swearing in of the new government in December 2011. In Holland, 208 days elapsed from the general elections of 1977 to the swearing in of the new government. Similarly, in Austria, it took 123 days to form a government after the elections of 1999.

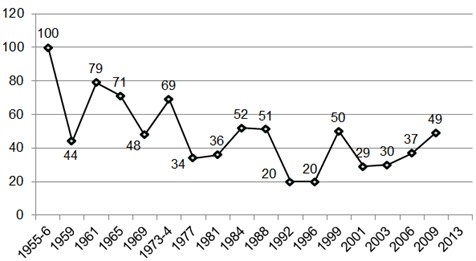

Figure 1: Time Taken to Form a Government in Israel (in Days)

This figure illustrates the number of days that it has taken to form a new government after elections in Israel. The numbers represent a 'gross' value: the total number of days from Election Day until the investiture of the new government.

As can be seen from the figure above, the process of government formation generally took longer during the first two decades of Israel's history than it does today. In 1955, no less than 100 days elapsed between the elections for Israel's third Knesset and the swearing in of the new government. After the elections for the fifth Knesset (1961), it took 79 days until the new government was sworn in. During the last two decades, however, the process has taken a maximum of 50 days. (Note that these figures refer to the total number of days between Election Day and the day that the government is sworn in. If the time between Election Day and the day when the President of Israel assigns the formation of the government to one of the members of the Knesset were to be deducted, the amount of time required would be shorter.)

Types of Coalitions and the Number of Coalition Partners

Since an incoming Israeli government must receive a vote of confidence from a majority of the Knesset (at least 61 members), and since no single party in Israel has ever held a majority of Knesset seats, all of Israel's governments have been "coalition governments.

Research distinguishes between three main types of coalition governments: an oversized coalition, a minimal winning coalition, and a minority coalition.

- An oversized coalition – An oversized coalition includes a number of parties whose combined strength exceeds the number necessary for a parliamentary majority. In such a coalition, if one of the partners leaves the coalition, the government does not necessarily lose its status as the majority government. In other words, the coalition has "spare" parties, at least in terms of the mathematics. The term commonly used by the media to describe this type of coalition is a "broad coalition," and in one particular circumstance, it is called a "national unity government."

- A minimal winning coalition – A minimal winning coalition is made up of a number of parties whose combined strength ensures a minimal parliamentary majority (i.e., half of the seats of parliament plus a few additional seats). In such a coalition, if one of the coalition partners leaves the coalition, the coalition loses its parliamentary majority.

- A minority coalition – A minority coalition is made up of a number of parties whose combined strength does not guarantee a parliamentary majority.

Since a minority coalition does not exist as an option in Israel, all of the governments that are formed after elections in Israel are either oversized coalitions or minimal winning coalitions. Of the 19 governments of Israel, there is a clear majority of oversized coalitions. Only three Israeli governments relied on a minimal winning coalition: the two governments of Menahem Begin (formed after the elections of 1977 and 1981) and the second government of Yitzhak Rabin (formed after the elections of 1992).

The tendency to form a government that relies on a broad parliamentary majority can also be seen from the relatively large number of parties that are included in Israeli governments. The outgoing coalition, for example, included no less than 6 parties (Likud, Israel Beiteinu, Atzmaut, United Torah Judaism, Habayit Hayehudi, and Shas). In this respect, Israel is similar to Finland and Belgium, in which the current governments also are made up of six parties. Most parliamentary democracies, however, have a lower number of parties in their governments, ranging from a single party to three parties (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Governments with Multiple Parties: The Number of Coalition Partners in the Government (December 2012)

Government Size and the Principle of Proportionality

Comparative studies that have examined the number of ministers allocated to each coalition partner have pointed to a principle of proportionality, according to which ministries are distributed in a manner that reflects the relative weight of each partner in the coalition. A partner with a large number of legislative seats receives a larger number of cabinet positions than a partner with a small number of legislative seats. The principle of proportionality is known in Israeli political jargon as the "coalition formula," according to which one ministry is allocated to a coalition partner for every X members of Knesset that it has. In the current situation, for example, if the coalition negotiations result in a coalition formula with a ratio of 1:4, we can expect that Yesh Atid will receive between four and five ministries, that Habayit Hayehudi will receive three ministries, etc. Naturally, this is not an exact science and there may be some divergence from this formula. For example, a party may waive one of its cabinet positions in return for receiving one of the three senior portfolios (finance, defense, or foreign affairs). Alternatively, it is possible for a party to receive fewer cabinet positions but to be compensated by receiving extra positions of deputy minister or chairmanship of Knesset committees. The ultra-Orthodox party United Torah Judaism, for example, does not accept ministerial appointments as a matter of principle, and is compensated by receiving the chairmanship of the Knesset Finance Committee or appointments as deputy minister.

When coalitions are formed, often the principle of proportionality is maintained with regard to the coalition partners, but the ruling party receives a number of portfolios that is higher than the party's relative weight in the coalition. This can be seen, for example, from the allocation of portfolios after the elections of 2009. At that time, the four coalition partners were allocated ministries based on the formula of one minister per every three members of Knesset: Israel Beiteinu received five portfolios, the Labor Party received five portfolios (slightly above the number mandated by the formula), and Shas and Habayit Hayehudi received four portfolios each (United Torah Judaism chose not to have a minister, as mentioned above). Prime Minister Netanyahu's Likud party, however, allocated 15 ministries to itself—a number that is far higher than its relative weight in the coalition and far above the formula for allocating ministerial posts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Distribution of Ministerial Portfolios Following the 2009 Elections

The number of ministers in the Israeli government has grown considerably over the years. The first Israeli government (sworn-in in 1949) had only 12 ministers. In contrast, the outgoing government (which was sworn-in in 2009) was the largest Israeli government in history and consisted of 30 ministers and nine deputy ministers. Until 1966, the number of ministers in Israel remained steady at no more than 18. There was a significant increase in this number when the government was formed after the elections in 1969. This was primarily due to the fact that the government that was formed was a broad coalition that included the two biggest lists—the Labor Alignment and Gahal. This government, known as a "national unity government," was made up of 24 ministers. The unity governments of the 1980s were also replete with ministers. Following three governments with a moderate number of ministers in the 1990s, which was attributed in part to a provision in the law that limited the size of the cabinet to 18 (this provision was canceled in 1999), the governments that have been established since the turn of the century have once again been very large. The peak, as mentioned previously, was 30 ministers in the outgoing government of Benjamin Netanyahu (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Number of Ministers in the Governments of Israel

This figure illustrates the number of ministers in the government formed after each Israel election since the establishment of the State. The values indicate the number of government ministers on the day of investiture ceremony until one week after (sometimes ministers are added to the government within a few days of the official inauguration).

The large number of ministers in the outgoing government is quite exceptional compared to the number of ministers found in other parliamentary democracies. While Canada (38 ministers) and France (34 ministers) currently have a larger number of cabinet ministers than Israel, the number of ministers in other parliamentary democracies is lower. For example, the current government of Sweden has 25 ministers, the current government of the United Kingdom has 22 ministers, the current government of Germany has 17 ministers, and the current government of the Netherlands has 13 ministers.

The unusually large size of Israel's government becomes even more striking when it is seen in comparison to the total number of members of parliament. At the beginning of the term of the current government, there were 30 ministers and 9 deputy ministers in the government—almost a third of the Knesset. There is no other country in which the size of the government relative to the size of the Parliament is so high. This phenomenon can be seen in Figure 5, which presents the percentage of ministers in comparison to the size of the parliament in Israel and other parliamentary democracies. Even when deputy ministers are left out of the calculations, 29 members (24.2%) of the 120-member Knesset are ministers in the government, which is an unusually high rate. In other parliamentary democracies, the number of ministers is lower or the number of members of Parliament is higher.

Figure 5: A Relatively Enormous Government: Percentage of Ministers Relative to the Size of the Parliament (December 2012)

Beyond the waste involved in having unnecessary offices, ministers without portfolios, and executive bodies of questionable benefit, having a government that is so large affects the functioning of the Knesset., since the more Knesset members there are serving as ministers, the less Knesset members there are who are available to do the important parliamentary work of serving on Knesset committees and overseeing the executive branch. It is hoped that the new government, which will be sworn in soon, will return to more reasonable numbers.

Dr. Ofer Kenig is an IDI researcher who heads the Political Parties Research Team of IDI's Forum for Political Reform in Israel.