A Consensual Approach to the Separation of Powers

The debate in Israel over the proper interrelationship among the three branches of government has become heated in recent years. IDI holds that any discussion of separation of powers should focus on functional boundaries among the branches, and on their mutual capacities for oversight. The following paper presents a series of proposals for addressing these issues and strengthening the separation of powers.

The article was published in June 2019 and updated in November 2022

Introduction by IDI Leadership

June 2019 - The debate in Israel over the proper interrelationship among the three branches of government has become heated in recent years. The very meaning of the principle of “separation of powers” is being contested. The crux of the challenge lies in a novel conception of “separation” as the erection of an impenetrable wall among the branches of government. According to this approach, each branch should focus on its own mission and avoid interfering in the affairs of the other: the Knesset should legislate, the courts should adjudicate, and the executive branch should formulate and execute policy. In essence, in a parliamentary system like Israel’s, where the executive and legislative branches are partially fused, this boils down to an argument against judicial review. Arising in part out of confusion provoked by a semantic particularity of the Hebrew rendition of “separation of powers”—hafradat rashuyot, literally “separation of branches”—the new conception runs against traditional notions of democracy as a system of checks and balances designed to distribute power so as to prevent tyranny.

In the traditional conception of the separation of powers, the executive, legislative, and judicial branches each have distinct functions, and enjoy a degree of independence necessary for the fulfillment of their roles, yet they interact with one another in important ways. Indeed, most democratic constitutions give the various branches of government explicit powers to oversee and, if necessary, check one another’s actions. This is not possible if there a wall “separating” them. Thus, any discussion of separation of powers should focus on functional boundaries among the branches, and on their mutual capacities for oversight.

This is especially tricky in a parliamentary system like Israel’s, where the separation of powers is partial to begin with. Not only does the coalition, almost by definition, control the legislative process in the Knesset through its majority of 61 or more supporting members, most Ministers and Deputy Ministers are also members of Knesset. Even the courts, which are theoretically independent, do not operate in a vacuum: in the absence of a constitution, their assessment of the legality of petitions must be based on government decisions and on Knesset legislation. In turn, the Knesset has the power to change laws as interpreted by the courts and implemented by the government, in order to adapt to a changing reality or changing public preference.

This description of the interrelationship between the branches of government is not only the de facto reality, but also approaches the desired state of affairs. To repeat: the democratic system is founded on the principle that excessive power, let alone absolute power, must never be concentrated in a single body. Distribution of power is the only proven antidote to tyranny. And it may be especially critical in a centralized democracy like Israel’s, which endures chronic security threats of an existential nature and lacks many of the checks on executive power that other democracies enjoy, such as a constitution, multiple chambers of parliament, or federal distribution of power.

However, distribution of power does not entail strict separation of authority. Complete separation of powers is neither possible nor desirable. On the contrary, a robust system of checks and balances relies mainly on carefully defined mechanisms of oversight, in particular the legislature’s oversight of the executive, and the judiciary’s oversight of the legislative and executive branches. In the Israeli context, it has become necessary to reevaluate the tools provided to the Knesset to oversee the actions of the government, and consider how these might be bolstered. It is also necessary to examine the means that would enable the judicial system to conduct effective judicial review of the other two branches.

The following paper presents a series of proposals (abbreviated in English) for addressing these issues and strengthening the separation of powers on the eve of the 2019 parliamentary elections. Taken together, we believe they will improve the current situation in Israel and ensure that we have three strong and independent branches of government, with a proper system of checks and balances governing the relationships among them. Most of these proposals are based on IDI’s comprehensive constitutional draft, “Constitution by Consensus,” prepared by a public council under the leadership of former Chief Justice (and Advisory Council Member) Meir Shamgar in the early 2000s. Others were formulated over the course of several years of research and dialogue with experts and politicians representing a wide range of approaches and opinions on these issues.

We have called on all the political parties and candidates running in this election to engage in serious debate on this critical issue. Such a debate is especially vital in the wake of several ill-considered initiatives to upset the balance among the three branches of government, which, if advanced, stand to weaken our government’s democratic structure. In contrast to much of the debate on these matters in recent years, which seems aimed to reengineer the system for the benefit of one part of the population, we have gone about formulating these proposals on the basis of a deep concern for the public interest as a whole. Although partisan politicians may reject them, responsible leaders will, we hope, see in them the basis for forging a broad national consensus around the effort to reinvigorate the institutions of Israeli democracy.

Yohanan Plesner Dr. Jesse Ferris Prof. Yuval Shany

President Vice President, Strategy Vice President of Research

I. The Status of the Judicial Branch

In the absence of a constitution, Basic Law: The Judiciary provides the legal basis for the principle of an independent judiciary. This law stipulates that in judiciary matters, those who have the power to exercise judicial powers are subordinate in exercising it to no one and to nothing, except the law itself. This is judicial independence in the substantive sense of the term; as for the independence of individual judges, there are legal arrangements in place for their protection, covering their salaries, terms of employment, and status.

Though substantive and personal independence are both anchored in law, in institutional terms the independence of the court system and its status as a separate “judicial branch” have no legal basis. Some administrative powers rest with the Minister of Justice (such as setting regulations for civil law procedures and establishing new courts; some are granted to the president of the Supreme Court and the presidents of other courts (for example, the management of the various courts of law); and some are shared by the Minister of Justice and the president of the Supreme Court (such as appointing the director of courts). Officially, the court system in Israel is an auxiliary unit of the Ministry of Justice.

We recommend:

1. The court system should be recognized as the Judiciary of the State of Israel. (See Appendix 1—Proposal for Amendment to the Basic Law: The Judiciary. Hebrew only).

2. The Judiciary should set the rules of procedure for the High Court of Justice, subject to the sole oversight of the Knesset. The rules of civil procedure should be set by the Minister of Justice, based on a proposal submitted by the Judiciary.

3. The Judiciary should be given control over its budget, and given the power to transfer funds among components of a budgetary line item. The Judiciary should prepare its own budget, to be included by the government in the general budget proposal it submits to the Knesset for approval. The government and the Knesset should be able to make changes to the budget, in consultation with the Judiciary, with the exception of the budget of the Supreme Court.

4. Employees of the Directorate of Courts should be defined as organizationally distinct from other civil service employees. The Judiciary should set its own administrative regulations, and the director of courts should be appointed by the president of the Supreme Court, to whom the former will report on the implementation of these regulations. The power to confirm the appointment of the director of courts, and to approve overall administrative policy, will remain with the Minister of Justice. The minister will also retain the power to oversee the implementation of policy.

5. The Minister of Justice should be required to consult with the Judiciary regarding the establishment of new courts and the definition of their powers.

6. Authority over human resource management, which currently rests with the Minister of Justice, should be transferred to the Judiciary.

II. Relations between the Judiciary and the Legislature

Since 1969, and increasingly since 1992, the courts have exercised judicial review over Knesset legislation without any basic law to define the specific process for doing so. On many occasions, the courts have had to conduct judicial review of primary legislation, including substantial judicial review of legislative content. This situation, in which judicial review of legislation is neither anchored in basic law nor defined in a way that reflects the particular sensitivity involved in annulling legislation, is unhealthy, and invites conflict among the three branches of government.

Rising tensions surrounding this issue have led to efforts by members of Knesset to pass an “Override Clause,” so named because it is designed to allow the Knesset to override court rulings that strike down legislation. Were this clause to be ratified, it would nullify judicial review of legislation, contravening a basic principle of constitutional law.

Effective oversight of legislation is important in any democracy. Judicial review is one of the main tools for protecting individual rights, both from the rule of tyrants and from the tyranny of the majority. It places restrictions on the parliament that are designed to protect basic constitutional values, and is a vital component of an effective system of checks and balances. However, while other democracies benefit from additional checks on legislative excess (such as a constitution, two legislative chambers, regional governments with substantial powers, or subordination to international courts of law), in Israel, judicial review is practically the only tool for institutional oversight of the Knesset. It should therefore be preserved.

In parallel, the Knesset’s powers of legislation must be better defined. Basic Law: The Knesset, states that the Knesset is Israel’s parliament. However, the law does not stipulate the Knesset’s powers of legislation. These powers are, in effect, mentioned only in the Transition Law of 1949, in which the Knesset is defined as the state’s “legislative body.” Most of the regulations governing legislation are currently to be found only in the Knesset Rules of Procedure.

In particular, no special process governs the passage of basic laws, which are the constitution-in-the making of the State of Israel, nor is a special majority required to pass or amend them (with the exception of basic laws that have been partially entrenched, such as Basic Law: The Government, or Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation).

The Knesset has extraordinary power to introduce basic laws. In conjunction with the absence of substantive or procedural limitations on legislating basic laws (such as an explicit requirement for a special majority), and the fact that Israel has only one legislative body, this power seems excessive. It is certainly unparalleled in any other Western democracy.

We recommend:

1. Pass a new Basic Law: Legislation and amend Basic Law: The Judiciary

In order to clarify and improve the relationship between the judicial and legislative branches in Israel, we recommend passing a new basic law—Basic Law: Legislation—and amending Basic Law: The Judiciary (see appendices 2 and 3, in Hebrew). The Basic Law: Legislation, would stipulate the legislative powers of the Knesset and define the unique status of basic laws. The amended Basic Law: The Judiciary would anchor the principle of judicial review in basic law.

These two changes should reflect the following five principlesConstitution by Consensus: Proposed by the Israel Democracy Institute, Under the Leadership of Justice Meir Shamgar, Israel Democracy Institute, 2005.:

A. Basic laws will require an additional, fourth reading in the Knesset, which will take place at least six months after the second and third readings.

B. Basic laws will require a majority of at least 70 members of Knesset in order to pass the fourth reading.

C. Judicial review of legislation will be carried out only by the Supreme Court.

D. Supreme Court hearings to annul legislation will require a panel of at least two-thirds of the full plenum of Supreme Court justices.

E. No override clause, either general or specific, will be legislated.

2. Legislate a Declaration of Human Rights

Alongside legislation to define the process of legislation and the power of judicial review, the Knesset should pass a Basic Law adopting a formal Declaration of Human Rights, along the lines of the detailed proposal contained in IDI’s Constitution by Consensus. Adopting such a declaration of rights, together with a new Basic Law: The Character of the State of IsraelSee IDI’s proposal for a Basic Law: The Character and Substance of the State of Israel, contained in the background materials. based on Israel’s Declaration of Independence, would solidify protection of basic freedoms and provide a firmer basis for judicial review, thereby minimizing friction between the judiciary and the Knesset. Passage of these basic laws would also constitute important steps towards enacting a full constitution for Israel.

III. Relations between the Executive and Legislative Branches

The government is dependent on the Knesset’s vote of confidence, and is obliged to carry out the Knesset’s resolutions, as is explicitly stated in the oaths of office taken by new ministers. However, in the reality of present-day Israel, the government’s control of the Knesset—by means of the automatic coalition majority it enjoys—means that the tables are turned, and in many respects, the government is not the “executive agency” of the Knesset, but rather the Knesset is the “legislative agency” of the government. The two biggest problems with this state of affairs are the poor quality of legislation coming out of the Knesset and the weak supervisory capacity of the Knesset over the executive branch. The proposals below seek to address these two challenges.

A. Curbing Private Legislation

The abundance of private legislation in the Knesset is unprecedented, and with the possible exception of Italy, has no parallels in the democratic world. Thousands of private member’s bills are tabled in the Knesset, but only a tiny proportion of them (4% in the 20th Knesset, average of 0.5% in the 21-24 Knessets) actually become law. Many remain simply “legislative declarations.” Dealing with the deluge of private bills comes at the expense of oversight over the executive branch, and leaves the Knesset with insufficient time and resources to improve bills that are in advanced stages of legislation.

Private MK Bills 2000–2015: Israel versus other democracies

We recommend:

Reduce the quantity and enhance the quality of private member’s bills

In order to channel private member’s bills toward responsible and high-quality legislation, we recommend:

1. Limit (gradually) the number of private bills that each Knesset member (MK) is allowed to submit for approval, to four bills per parliamentary session.

2. Limit the quota of private bills brought to preliminary reading in the Knesset to 15 per week (approximately half the number currently put forward).

3. Require MKs to include in the explanatory note of every private bill, details of the estimated cost and other implications of the bill (on society, on the environment, on international treaties to which the state is a signatory, and so on). The Knesset presidium (comprised of the Speaker of the Knesset and the Speaker’s deputies) should not permit bills lacking these details to be brought to preliminary reading in the plenum.

4. Allocate budgets for researchers from the Knesset Research and Information Center to help MKs improve the quality of their bills, and help them gain access to relevant information from various entities in government ministries.

B. Enhancing Knesset Oversight of the Government

An important role of the Knesset is to serve as an “oversight body” over the executive branch. The main arena in which this role finds concrete expression is in Knesset committees, which are expected to conduct their work more professionally and efficiently than the work being done in the Knesset plenum. In practice, committee oversight is relatively weak and ineffective. This is rooted, to some extent, in structural factors (for example, the fact that the government controls most of the Knesset’s activity due to its built-in coalition majority in the plenum and in the committees, and the fact that the size of the Knesset is relatively small), and also in various procedural and regulatory factors, as detailed below.

Issue 1: A relatively small number of MKs devote their time to parliamentary work, particularly—to the work of Knesset committees.

The Knesset is one of the smallest parliaments in the world. Due to the tendency in Israel to form relatively large governments, only around three-quarters of the 120 members of Knesset have time to devote to committee work. And many of those are members of multiple committees, resulting in poor attendance at committee meetings, which meet on the same days and at the same hours. This weakens the committees’ ability to fulfill their oversight and monitoring roles successfully.

We recommend:

Strengthen the committees by increasing the number of MKs available for committee work

1. Pass a full-fledged “Norwegian Law”, according to which a member of parliament who joins the government resigns from the Knesset, making way for another MK from the same party to take his or her seat. This will make it possible for more Knesset members to serve as active parliamentarians, instead of the current situation, in which many do not fulfill this role after being appointed as ministers or deputy ministers.

2. Limit the membership of permanent committees to a maximum of nine (with certain exceptions, such as the House Committee, the Finance Committee, and the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee).

3. Limit the number of permanent committees on which a member can serve.

4. Impose sanctions against MKs who do not attend committee meetings.

5. Add a day to the Knesset’s official work week, and dedicate it to committee work.

Issue 2: Knesset committee structure does not match up with corresponding ministries

The areas of responsibility of the Knesset permanent committees are defined by topics rather than by relevant ministry. This substantially reduces their ability to oversee the government’s activities, since it is difficult for committee members to conduct a thorough examination of the work of the various ministries relevant to these topics.

We recommend:

Create stronger correspondence between Knesset committee responsibilities and main government ministries

Issue 3: Knesset committees suffer from a lack of authority and mechanisms for monitoring the activities of the executive branch and for tracking implementation of their own oversight activities

We recommend:

Bolster the committees’ oversight powers by introducing oversight and monitoring mechanisms:

1. Hold committee hearings on specific issues. In the 20th Knesset, a number of issue-based hearings were held, and proved to be efficient and effective oversight tools. Such hearings should be formalized in the Knesset Rules of Procedure. We do not propose to introduce personnel appointment hearings at this stage, because in Israel’s political culture they likely would cause greater damage than benefit.

2. Empower permanent committees to obligate the government to hold a discussion on a particular issue, subject to a vote in favor by two-thirds of committee members.

3. Create a sub-committee for budget issues in all permanent committees, responsible for monitoring expenditures of the relevant ministry, as well as a sub-committee responsible for monitoring state audit reports.

4. Introduce a “mandatory auditing package” for all permanent committees, requiring the relevant minister to report to the committee in person every six months; setting up a sub-committee to monitor implementation of the committee’s decisions; and publishing an annual report summarizing the committee’s work at each session.

5. Require all committee chairs to hold legislative follow-up discussions on the need for supplemental regulations to laws advanced by the committee in question, and other measures necessary to ensure that legislation is fully implemented. Mandate that the committee produce a report presenting all the legislation that the committee has advanced, which regulations have yet to be passed, and where implementation has not yet begun.

Issue 4: Guidelines for committee work are unclear

Regulations defining best practice for the work of the Knesset committees are defined in Basic Law: The Knesset, and in the Knesset Rules of Procedure. Conspicuous in their absence from this list are clear rules defining the work of the Knesset committees and the powers of committee chairpersons and other professional position holders (including professional staff such as legal advisers and researchers).

We recommend:

Produce a handbook for Knesset committees

This handbook would define official rules for Knesset committees’ work and the authority of those who hold committee positions. Among other issues, the handbook would help clarify the following:

• Define the position of Knesset committee chairs (powers and responsibilities).

• Define the deadline for placing issues on a committee agenda.

• Define the minimal period of time for advance notification of the convening of committee meetings.

• Set minimum quorum levels for holding committee discussions and for taking a vote.

• Make it mandatory to submit documents to the committee in advance of any discussion.

• Define the order of speakers at committee discussions.

Issue 5: Rapid turnover in Knesset membership makes it difficult to develop expertise and professionalism in the committee’s field of oversight.

We recommend:

Boost professional support for MKs

1. Strengthen the status of the Knesset Research and Information Center, and ensure its more efficient utilization.

2. Expand the Knesset committees’ professional support staff.

3. Improve training of MKs, including by means of a preparatory workshop for new MKs under university auspices.

Issue 6: The Knesset is too small in comparison with the work burden

The Knesset is one of the smallest parliaments in the world (even in comparison to population size) and therefore, MKs bear a particularly heavy work burden, especially in the parliamentary committees. To deal with the problem of a shortage of active Knesset members, the 20th Knesset passed legislation under which a minister resigns from the Knesset and is replaced (known as the “Norwegian law”), and the expanded Norwegian law was passed by the 24th Knesset. However, this is only a partial solution, and not necessarily the desired one: First, the law gives rise to new problems such as creating a new status of a “conditional” MK, a high turnover of MKs which reduces their professionalism, and a weakened connection between MKS and government ministers. Second, even if the full Norwegian law is adopted, and all the ministers and deputy ministers resign from the Knesset and are replaced by active MKS, the Knesset will still be too small to efficiently carry out all its tasks.

We recommend:

1. At this stage, to leave the current Norwegian law untouched. In order to increase the number of MKs available for parliamentary work, the full Norwegian law should be adopted, requiring all ministers and deputy ministers to resign from the Knesset (except for the Prime Minister).

2. To leave the “revolving door” mechanism in place, enabling those who resign from the Knesset under the Norwegian law, to return and serve in it. Although there are also flaws in this system (it creates a status of “conditional” MKs), yet in the current reality, revoking this system would create absurd situations. For example, if the Prime Minister dismisses ministers from a particular coalition faction, they cannot return to be MKs throughout the entire candidacy, even though they are the most senior politicians in their party.

3. To lessen the damage caused to the connections between MKs and the government, checks on the Knesset and government should be strengthened. Two important mechanisms are oversight hearings in Knesset committees and question time in the plenum.

4. In the long term, the number of MKS should be increased (for example, to 180 members). Such an increase would enable MKs to carry out their duties more efficiently and with greater seriousness, enabling them to specialize in specific areas, and would also enable the Norwegian law to be revoked. This reform should only be enacted after a lengthy and serious process in the Knesset and public discussion and preferably after broad consensus in the Knesset.

IV. The Executive Branch

According to Section 1 of the Basic Law: The Government, the government of Israel is the state’s executive branch. The government’s ability to function is grounded in a vote of confidence by the Knesset, to which it is responsible for its actions. Currently, neither the role of the executive branch nor its obligations to the public are defined in Basic Law: The Government. The status of the professional civil service operating under government auspices is also not defined by law. This raises a number of problems, laid out below.

Issue 1: Governments in Israel are too large

Unlike other parliamentary democracies around the world, Israel tends to have large governments. The fact that there are many government ministries and ministers has negative consequences, both for the government’s efficiency (due to the complexity of the decision-making process and the unclear division of powers among the various ministries) and for the Knesset (since ministers are unavailable for parliamentary work).

Number of Ministers in Governments around the WorldData accurate as of January 2019.

Number of Ministers in Israeli Governments (upon initial formation of government)

We recommend:

Limit the number of ministers and impose mandatory resignation of ministers from the Knesset

1. Limit the size of the government’s size to 18 ministers and 4 deputy ministers by Basic Law.

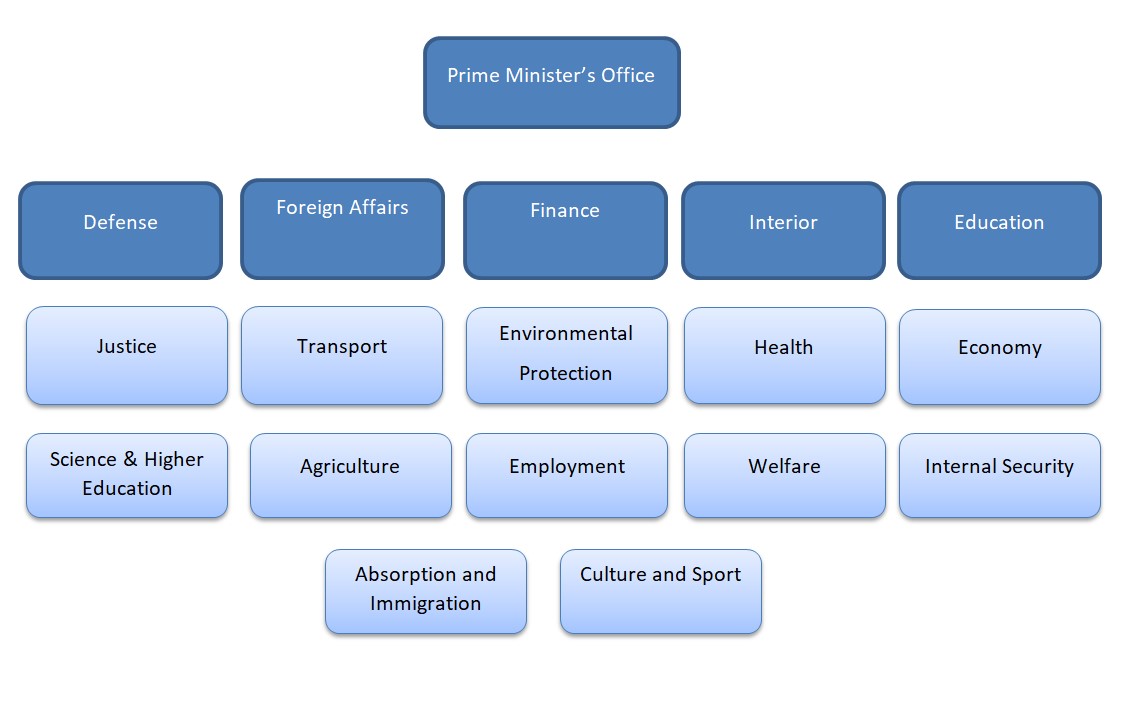

Proposal for a government structure with 18 ministries:

2. Pass a full “Norwegian law”, according to which any member of Knesset who is appointed as a minister (excluding the prime minister) will be required to resign from the Knesset, and will be replaced by another representative from the same political faction.

Issue 2: Excessive friction between the Knesset and the Ministerial Committee for Legislation

The legislative interface between the government and the Knesset is problematic in two respects: First, approximately half the legislation passed in Israel originates in bills presented by the government (this is a low proportion relative to other parliamentary democracies, in which the majority of legislation is based on government bills). Government bills, which are almost automatically approved by the Ministerial Committee for Legislation, are usually very complex. When these bills reach the Knesset, members have neither the time nor the necessary knowledge to debate them in any depth. The Omnibus Arrangements Law, passed hurriedly in conjunction with the budget, is an extreme example of government legislation that does not permit the Knesset to hold a detailed debate of its implications, and in effect— makes the Knesset a rubber stamp for government legislative initiatives.

On the other hand, the deluge of bills submitted by individual MKs creates a need for a governmental filtering mechanism, a role that is currently played by the Ministerial Committee for Legislation. Due to the large number of these bills, there is no opportunity for in-depth committee discussion, and the default is simply to approve bills proposed by coalition members, and to reject those put forward by members of the opposition. Thus, the Committee is transformed from a body that is supposed to weigh each bill based on the criterion of the public’s interest, into a fast track for private bills of a partisan, and often questionable nature. In recent years, Knesset members have used the Committee to advance bills proposed by individual MKs in areas that would ordinarily require considerable preparatory staff work by government ministries, without making any real effort to direct this legislation through government channels, and also to advance MK’s private bills of dubious constitutionality, and to which the government’s own legal advisers are opposed. This creates further friction between elected officials and the civil service.

Our Recommendation: Improve the legislative interface between the government and the Knesset by limiting the use of the Arrangements Law and reducing the number of private bills

1. Define the substance of the executive branch in Basic Law: The Government (the government and other bodies that can be defined as being part of the executive branch), as well as the responsibilities of the executive branch toward the public (see Appendix 4, in Hebrew).

2. Pass a Basic Law: The Civil Service, which will ensure the independence and professionalism of the civil service, its composition, its hiring practices, and its responsibilitiesFor more details, see Assaf Shapira, Relations between the Professional and Political Echelons, Israel Democracy Institute website, 2019..

3. Strengthen the professional capacity of Knesset committees and the ability of MK’s to understand government bills, comprehend their details, and critique them.

4. Limit the government’s ability to use the Arrangements Law instead of regular legislation.

5. Significantly reduce the number of MKS personal bills (see recommendations in the section on the Knesset above).

6. Require the Ministerial Committee for Legislation to act with transparency regarding the reasons for rejecting individual members’ bills, and also permit Knesset members to appeal against the Committee’s decisions (on condition that strict limitations are placed on the number of private bills).