In Praise of Normalcy

Despite all the fears, voter turnout was quite respectable (the third-highest rate in the seven elections this century).

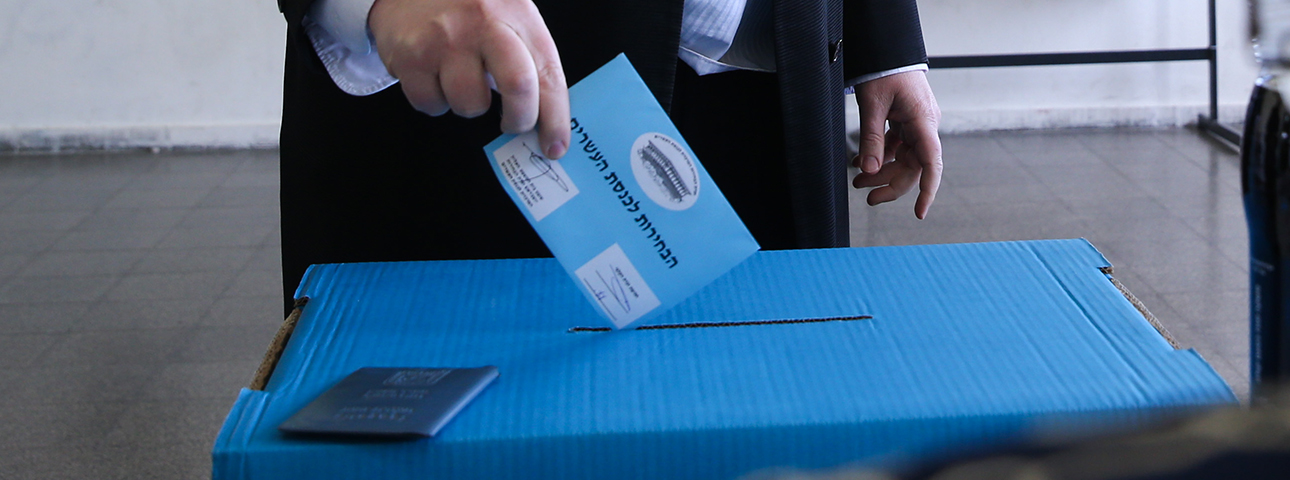

Flash 90

Israelis woke up depressed when it became apparent that the rerun election had not produced a clear winner, and that the political system remained paralyzed. But when the dust settles, it may turn out that there was indeed a winner after all, one that rises far above all the squabbling parties: normalcy.

First, the overall picture is that democracy has grown stronger. Despite all the fears, voter turnout was quite respectable (the third-highest rate in the seven elections this century). There were no incidents that interfered with the process, and we have not heard any allegations of fraud on a massive scale. We can also identify another positive trend: The number of lists that passed the electoral threshold (nine) is the smallest in the country’s history, and we are seeing a welcome tendency to form political blocs. The most radical extremists (Otzma Yehudit) and fly-by-night lists (the now demised Zehut) did not succeed in getting seats in the Knesset.

Second, who is the kingmaker in Israel politics? For years, this rewarding role has been played by a minority with its own distinctive ideology – the ultra-Orthodox. This is a legitimate situation in a democracy, but it has wreaked enormous damage. The disproportionate power of the ultra-Orthodox fueled the Israeli Kulturkampf. However, their continuing drift toward the Right has left the ultra-Orthodox parties with only one trick in their hands. In these elections, the veto power was finally transferred from the ultra-Orthodox camp to Avigdor Liberman and his party. Liberman is striving to wield this power in order to coerce the two big parties to form a national unity government. If Liberman holds firm to this demand, without shooting off excessively sharp barbs against the ultra-Orthodox and Arab Israelis (though this is very real concern), he will serve as the catalyst for the return of normalcy to Israeli society.

Third, Netanyahu’s attack on the Arab citizens of Israel is not normal, by any liberal, Jewish or human standard. Their response, in the form of a higher turnout on Election Day, is a sign of their future course: Most of them are eager to find their place in Israeli society on an equal footing. For the first time ever, we heard their political leader entertain the option of sitting in the government. For the first time, it is possible that as the leader of the parliamentary opposition he will be an official member of the establishment. The road ahead is long and winding, but these modest beginnings symbolize a journey that will end in normalcy.

Fourth, aside from Netanyahu’s personal fate, the main issue of these elections was the future of the rule of law in Israel. Netanyahu and some of his supporters set us on a dangerous path that would weaken the oversight mechanisms that are part of any functioning democracy. The High Court of Justice would have been stripped of power and its members selected in a political process; the ministries’ legal advisers would have lost their independence of their ministers; the media would have been “tamed”; and human-rights organizations would have been stifled. The election results seem to have staved off all these “benefits.” Israel will again be a normal democracy that respects the system of checks and balances and does not adapt the rules of the democratic game in order to satisfy personal or momentary needs.

Fifth, the elections have created a window of opportunity for a change in Israel’s system of government in a way that could make the political system more stable in the coming years. Taken together, the Likud and Blue and White hold a parliamentary majority and have no need for junior partners in order to form a coalition. They can agree to pass a law stipulating that after the next election, the leader of the party that wins the most votes automatically becomes prime minister. This change will significantly strengthen the large parties at the expense of the small ones, and that would all be for the good.

So if the present tie between the two leading parties is not broken, the possibility of a change in the law and new elections – in which two large blocs would run against each other, ending with a clear-cut result – would be the best outcome for a country that yearns to be normal.

The article was published in the Jerusalem Post.