Immunity for the Prime Minister: Explainer

IDI experts explain Israel’s immunity law, what happens when it’s requested and what the implications may be for the political system.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Immunity for the Prime Minister

Why do Knesset members enjoy immunity from criminal prosecution?

Parliamentarians enjoy immunity from prosecution in order to allow them to carry out their duties without fear of interference or harassment by the incumbent government. In the past, immunity for members of parliaments, which on the surface violates the principle of equality before the law, was justified by the fact that powerful executives harassed the people’s elected representatives, in an attempt to prevent them from carrying out the jobs.

If immunity is so important for Knesset members, why isn’t it automatic?

Immunity from criminal prosecution stands in tension with the rule of law and to the principle of equality before the law. Immunity conveys a message that elected officials are above the law, and so--it is essential to limit its use to cases which arouse a genuine fear that an indictment is being submitted for the sole purpose of harassing the defendant on political grounds. Granting immunity can only be justified in cases in which there are strong grounds for doing so, and especially –when the MK’s alleged criminal act was committed in the course of performing his or her duties as an MK. Granting immunity in inappropriate circumstances is liable to undermine the principle of equality before the law and convey the message that criminal behavior by elected officials can be condoned.

What is parliamentary immunity?

There are two types of parliamentary immunity—substantive and procedural. Substantive immunity protects actions directly related to the Knesset member’s official function. Such immunity applies mainly to expressions of opinion, votes, and activities that are essential to the performance of the MK’s duties. Substantive immunity negates any criminal liability, does not expire when the MK returns to private life, and cannot be revoked. Such immunity is extremely limited and is granted only within “the bounds of the inherent risk” associated with the MK’s activity. Its goal is to permit MKs to speak, vote, and act freely in the course of fulfilling their parliamentary duties, without fear that charges or lawsuits will be brought against them. It is not intended to encourage MKs to commit criminal acts and certainly does not apply to graft or other serious criminal offenses.

Procedural immunity protects MKs from standing trial while in office, and relates to any offense for which they have been indicted. In the past, MKs enjoyed procedural immunity automatically; the Attorney General had to specifically request the Knesset to revoke it when he deemed that appropriate. In the wake of several cases in which the Knesset declined to revoke an MK’s immunity, and which triggered harsh public criticism of the Knesset and forced the High Court of Justice to intervene, the law was revised in 2005. Today, no MK enjoys automatic immunity, but he or she can request the Knesset to grant immunity on various grounds. This means that having no immunity is now the default rule;, the Knesset must specifically vote to grant it.

What is the goal of procedural Immunity?

Procedural immunity is intended to protect Knesset members from being harassed by the executive branch. The traditional justification for such immunity is to protect members of opposition parties from political persecution by the government.

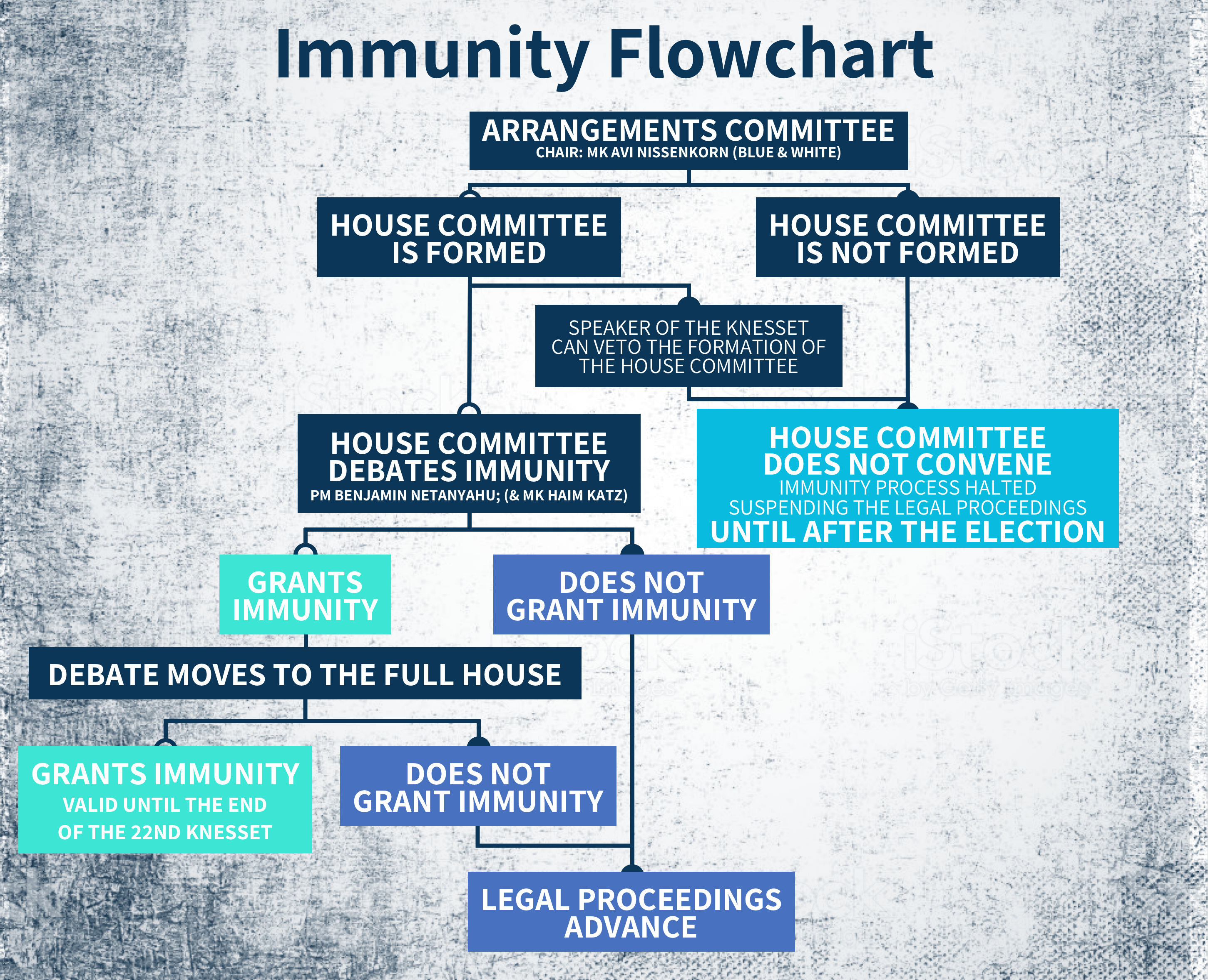

What is the procedure for granting immunity?

After the Attorney General sends the indictment to the accused MK and to the Speaker of the Knesset, the MK is given 30 days in which to request that the Knesset grant him or her immunity. When such a request is submitted, the Knesset House Committee must consider it as soon as possible. After it hears the arguments presented by the MK and by the Attorney General, the House Committee is meant to vote on the matter. Its decision to grant immunity must be ratified by the Knesset plenum. The validity of the immunity holds only for the duration of the term of the Knesset that granted it. If reelected, the MK can submit a new request for immunity to the next Knesset.

Can the deliberations on granting immunity take place if the Knesset House Committee has not been formed?

The Knesset’s legal counsel has ruled that if the House Committee has not been formed, a hearing on granting immunity cannot be held. Nevertheless, there is no legal ban on establishing the House Committee today, by the lame-duck Knesset, if a majority on the Knesset Arrangements Committee decides to do so. Note that the law requires the Knesset to deal with immunity requests as soon as possible, and this might be interpreted to mean that the Knesset is obligated to establish the House Committee now, and consider an immunity request without delay.

Why is the Prime Minister requesting immunity if he knows that there is no House Committee to consider it?

A request for immunity is likely to lead to a delay in criminal proceedings against the Prime Minister. Without such a request, the indictment against him can be submitted to the courts this coming Sunday. A request for immunity is meant to be heard by the Knesset House Committee, but in light of the position of the Knesset’s legal counsel, unless a decision is taken to form that committee, the matter will remain on hold until after the next general election. Any decision, when taken, can be appealed to the High Court of Justice, a procedure that is likely to postpone the submission of the indictment for several months. The best way to understand the Prime Minister’s move is as a legal tactic to block, at least temporarily, his having to face the court.

What are the grounds for granting immunity?

The law cites four grounds for granting immunity to a Knesset member: (1) The issue is one of substantive immunity, and the MK is entitled to protection of his or her freedom of expression. (2) The prosecution is not acting in good faith or is discriminating against the MK. (3) The Knesset has already conducted disciplinary proceedings against the MK, and there is no public interest, given the leniency of the offence, to place him or her on trial. (4) Criminal proceedings would cause serious damage to the Knesset’s operations or to the representation of the people, and, in light of the “gravity, substance, and circumstances of the alleged offense,” the public interest would not be harmed, if no trial would take place. No MK or government minister has been granted immunity since the law was amended in 2005. There has never been a court ruling on the fourth argument, but given the clause quoted above, it is reasonable to assume that it is not intended to protect MKs against being tried for serious offenses, but only for relatively minor wrongdoings.

Which of these grounds can the Prime Minister cite as the basis for his request for immunity?

At present, one can only speculate about the Prime Minister’s planned choice for the grounds for his request for immunity. But we can already note that the present circumstances do not clearly fit any of the criteria cited in the law. First, there is no clear link between the charges against him and his parliamentary duties. The indictment focuses mainly on actions aimed at gaining personal benefits or which clearly deviate from the conduct expected of a representative of the public. Given the nature of the charges and especially the fact that they relate to serious forms of corruption, it is very difficult to claim that they are inconsequential, and that a failure to proceed with a trial would not constitute a serious blow to the public interest. So the fourth argument, that the offense is minor, does not seem to hold here.

This leaves only the “grounds of persecution” as an argument supporting the granting of immunity—that is, that the prosecution is not acting in good faith or is discriminating against Netanyahu. But despite the fact that such arguments may enjoy the sympathy of his supporters, to date-- no solid evidence has been presented to buttress the allegation that all Israeli law-enforcement agencies, from the police to the State Prosecutor’s Office, to the Attorney General, have cooked up a plot against the Prime Minister. Here, prima facie and as long as no solid evidence to the contrary is presented, this argument has no basis in fact.

What are the implications of the fact that the immunity procedure is a quasi-judicial process?

We are not dealing with a bill submitted to the Knesset or a usual political procedure, in which various agreements can be forged that make it possible for the Coalition (or the Opposition) to function. This means that Knesset members cannot trade their votes in the House Committee or plenum for a concession by the other side. When it comes to a grant of immunity, they have independent discretion as to how to vote and they cannot promise to vote for or against immunity, before they have heard the arguments or examined the evidence; they certainly cannot receive benefits of any kind whatsoever, not even in the form of a coalition agreement; in fact, that could be deemed bribery.

Is the process subject to judicial review?

Yes. Granting immunity involves a quasi-judicial proceeding, and under the Basic Law: The Judiciary, the High Court is empowered to review it. A MK requesting immunity must submit compelling evidence of lack of good faith or discrimination underlying the prosecution’s decision to press charges, or show that the crimes cannot be deemed serious, in light of their nature and the circumstances surrounding them. If such evidence is not submitted, but the request for immunity is nevertheless granted, the High Court can intervene and strike down the House Committee’s decision to grant immunity. It is conceivable that the High Court, upon concluding that the required evidence had not been presented, would issue an injunction against such a decision and request the Knesset to reconsider the grant of immunity.

But why can’t the legal proceedings against MKs be suspended until after they leave office?

Because Israel has no term limits for Knesset members or Prime Ministers, a freeze of legal proceedings as long as the person charged remains in office could last for many years and severely undermine the possibility of getting at the truth, along with violating the principle of equality before the law. A situation in which a person suspected of criminal activity continues to serve in high public office would strike a severe blow to public trust in the government and could even make it possible for the suspect to take actions that would interfere with the investigation, or to commit additional crimes.

What is the customary practice in the rest of the world?

The Anglo-American system only recognizes immunity from arrest or imprisonment. In Europe, too, where there are various provisions, some of them similar to those in Israel, the trend is to limit the immunity enjoyed by public officials. For example, in the 1990s, France and Italy rescinded automatic immunity against trial, leaving in place mostly the protection against arrest and imprisonment. International organizations, such as the EU, emphasize that immunity is especially important in countries in which the political opposition faces a real threat of persecution.