Working from Home: Pre-and Post-Coronavirus

The coronavirus has made working from home much more prevalent, and has many advantages, including improving efficiency and providing workers with more flexibility. But how do we ensure that it does not increase wage disparities and provide even more advantages to those who are already the higher earners? IDI experts weigh in with recommendations to ensure that all sides benefit

Illustration | Flash 90

Executive Summary

Working from home at least one day a week offers many advantages to all the relevant players. Workers can enjoy greater flexibility in their work hours and a better work-life balance, by saving time on commuting, being able to manage their own time, and more. Employers in the business and government sectors can save on costs due to reduced expenses on energy, office equipment, employees’ travel, and more, and benefit from greater efficiency thanks to the higher productivity of employees working from home.

A shift to working from home at least one day a week can enhance the wellbeing of all of Israel’s residents, as it will significantly reduce road traffic and commuting time for workers unable to work from home due to the nature of their jobs. Less traffic will also mean less pollution of the air we all breathe, leading to better health and lower mortality, as well to fewer casualties from road accidents. In addition, reducing traffic helps in upgrading overall work productivity, by saving time spent waiting in traffic, and thus – improves the economy’s competitiveness, along with accelerating economic growth and employment.

Until now, it was “common knowledge” that transitioning to working from home at least one day a week can help narrow socioeconomic gaps by providing easier access to the labor market for population groups, such as those living on the country’s periphery, individuals with disabilities, and parents of young children, for whom flexible working hours and less of a demand for physical presence in the workplace, make a big difference.

However, various surveys conducted in Israel and around the world have revealed a troubling picture in which those who have been most able to reap the benefits of working from home are workers who are better positioned in the labor market (with academic qualifications and high salaries), while for the most part, those in lower-ranking positions – are mainly employed in jobs that cannot be performed from home (waiters, cleaners, sales persons, sales, and the like).

Moreover, the coronavirus crisis has uncovered a variety of challenges in the transition to working from home, which, without careful government intervention may in fact, lead to the opposite outcome, and broaden social and economic gaps.

It is the government’s responsibility—both as the country’s largest employer and as the driver of its socio-economic policy—to ensure that increasing the number of those working from home does not generate greater inequality. This must be done by ensuring a proper working environment, internet connectivity for all the residents, including those living in far places and disadvantaged groups; and providing good conditions for every employee working from home. This can be accomplished by advancing relevant legislation and addressing the need for domestic workspaces when planning housing in the future. These measures are essential to cope with the challenges of working from home.

It is important to recognize that there are still many challenges in working from home, including for example: the blurring of and the boundaries between time designated to work and time designated to personal activities; the risk of drifting into working at unconventional hours (whether by the employee’s choice or not); a lack of interaction with others, a sense of loneliness, reduced teamwork; and lack of basic working conditions, such as a suitable desk and chair, computer, lighting, and more.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize that most of these challenges are more relevant to working from home on a permanent basis, and less so in the case of working from home for one or two days a week.

The government must take action on several key issues:

• Formulate and institute clear rules for working from home, and adapt labor legislation accordingly (flexible working arrangements are widely spread and accepted in the world).

• Upgrade Israel’s internet infrastructure to high-speed broadband (this is largely a regulatory issue; the emphasis on competition over pricing in the government’s communications reforms has come at the expense of investment in the needed infrastructure)

• Provide easy access to training programs and courses for both employees and managers on subjects such as time management when working from home, and on using the digital tools that are necessary for remote working. This can be done via Israel’s network of community centers, the education system, higher education and vocational training institutions, as well as through training on site in the workplace, subsidized by the government.

• Provide financial assistance for businesses (mainly small and medium-sized) to invest in making the necessary adaptations for remote working (information security, communications systems, remote access, etc.) by subsidizing at least 30% of the costs. This assistance can be provided via tax benefits or through direct reimbursements.

• Develop methods for tracking and assessing employee performance and outputs when working from home. As the country’s largest employer, the government should provide mechanisms for evaluating the output of public sector employees who are working from home. If it is successful, this will create a significant change, that will upgrade the efficiency of the entire public sector and improve the services provided to residents. (It can be assumed that the business sector will find ways to do this even without government assistance).

• Ensure that vulnerable populations benefit from the possibility of working from home, by guaranteeing access to computers, internet connectivity, and other required conditions.

Background

Working from home or "remote working" has become in recent years a trend that can no longer be ignored. With the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, this trend has gained momentum and has become even more widespread. Under the social distancing conditions imposed in response to the virus, many workers worldwide have been working from home, in what has amounted—in effect – to a global experiment. While the pandemic is still raging, it is already possible to identify the benefits and the challenges we face, on the road toward making working from home a feasible employment option that maximizes benefits for all parties involved.

The advantages of working from home are many, and include—greater satisfaction among both workers and employers more leisure time and a better work-life balance for employees; greater flexibility in working hours; and increased work productivity. Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of working from home in terms of increased productivity: A U.S. study revealed an increase of 4.4% in productivity among patent examiners working from home (Sentz, 2019), while a study in China found an improvement of 13% in the performance of call center workers who worked from home, and a rise of over 20% in the company’s overall productivity. The Chinese study also found a decline in feelings of burnout and a rise in satisfaction among those working from home (Bloom et al., 2015), while the findings of a field experiment in the U.S. showed that workers were willing to “give up” 8% of their salary in exchange for the possibility of working from home (Mas and Pallais, 2017). Not surprisingly, attitudes on working from home are related to the worker’s parental status: in Germany, satisfaction was greater among employees without children who worked an extra hour a week from home (Arntz et al, 2019).

In Israel as well, there are indications that working from home enhances worker satisfaction. A pilot program conducted among workers in the public sector indicated a rise in satisfaction among both managers and workers, alongside increased productivity. The success of this pilot led to a decision to encourage working from home, and to expand it to employees with lower wages and parents of young children whose jobs require a large volume of writing and preparation (Civil Service Commission website, 2020). Another pilot program, held from 2012 to 2014 at the Israel Patent Office, found increased productivity and satisfaction among workers, a decline in absenteeism, and a saving of resources. Similarly, the Patent Office was more successful in recruiting new workers (Ministry of Finance, 2018), with a decision being made to implement remote working on a routine basis while investing in improving and scale-up working from home (Ministry of Justice, 2018)It should be remembered that with pilot programs of this sort, the organization and the type of work involved are not selected at random; rather, the experiment is conducted with organizations and employees suited to working from home..

In addition, working from home cuts down travel in private cars and on public transport, thus reducing the volume of road traffic and the number of traffic accidents, along with other benefits. A 2018 study found that offering workers the option of working 15% of their weekly hours from home produced the highest market benefit of any other intervention aiming at reducing use of private cars in Israel (Ecotraders, 2018). Moreover, encouraging working from home (which reduces private car use) leads to reduced exposure to air pollution, a factor that contributes to the early deaths of around 2,200 people in Israel each year (Ministry of Finance, 2018).

It is generally thought that working from home helps reduce inequality, in a way that it increases access to distant workplaces and broadens the employment options open to people living in the periphery, people with disabilities, parents of young children, and others. Similarly, working from home contributes to reduce income gaps between men and women (Arntz et al., 2019).

On the other hand, the coronavirus crisis has shown that working from home can also widen socioeconomic gaps, in a way that most of the workers given the option of working from home are those with an academic degree and/or high salary, while this option has been unavailable or irrelevant for a sizable percentarge of the more vulnerable workers in the labor market (production workers, waiters, salespersons, hairdressers, cosmeticians, and other service providers). Moreover, a considerable number of the more vulnerable workers suffered from a lack of the essential conditions for working from home, such as a Wi-Fi connection, a computer, an office chair, a desk, and a quiet corner at home from which to work.

In light of all the above, we ask: Given that the widespread introduction of working from home can benefit all players in the economy, what are the main barriers to this development, and how can these be addressed?

Pre-Coronavirus Work from Home – Worldwide

In the European Union, 5.2% of employees routinely worked from home in 2018, and the number of those who sometimes work from home increased from 5.8% in 2008 to 8.3% in 2018 (Eurostat, 2020). The 2015 European Survey on Working Conditions found that, on average, three out of four workers had some degree of flexibility in their working hours, and that this flexibility increased with the worker’s level of education and status at work. Flexibility is mainly evident in Scandinavian countries, which have a high employment rate among women and relatively small gender gap in labor force participation. The Netherlands is unusual in that flexibility in working hours goes hand-in-hand with part-time employment, particularly among women, and the gender gap in hours worked is on the rise (OECD, 2016).

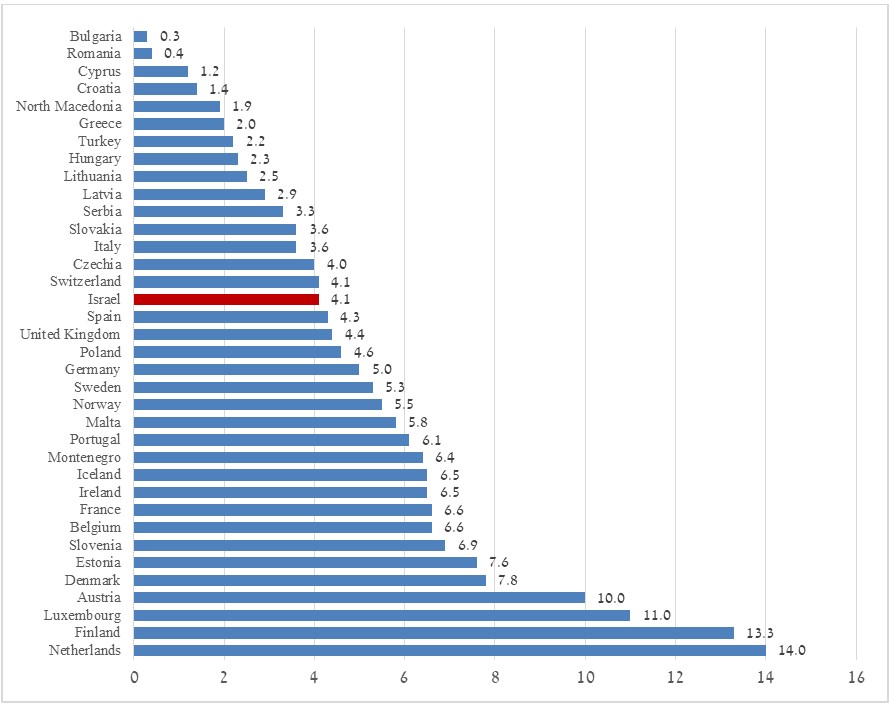

Compared to European countries (see Figure 1 below), the prevalence of work from home in Israel before the coronavirus (2018) was relatively low – at 4.1%, compared with 14% in the Netherlands, 13.3% in Finland, 11% in Luxembourg, 10% in Austria, almost 8% in Denmark and Estonia, and around 7% in Slovenia, Belgium, France, Ireland, and Iceland. In Sweden (5.3%), Germany (5%), and Britain (4.4%), the percentage of those working from home was relatively low.

Figure 1. The percentage of workers routinely working from home, as a percentage of all workers, 2018

Source: Authors’ analysis of EU data (Eurostat, 2020) and data from Israel’s Social Survey (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2018)

The percentage of women working from home in the European Union is higher than that of men (5.5% versus 5%, respectively). In France and Luxembourg, the gap is larger, with 8.1% of women working from home compared with 5.2% of men in France; and 12.5% of women versus 9.8% of men in Luxembourg. It should be noted that some EU countries (such as Denmark and the Netherlands) display the opposite trend, with a greater percentage of men working from home than women (Eurostat, 2020).

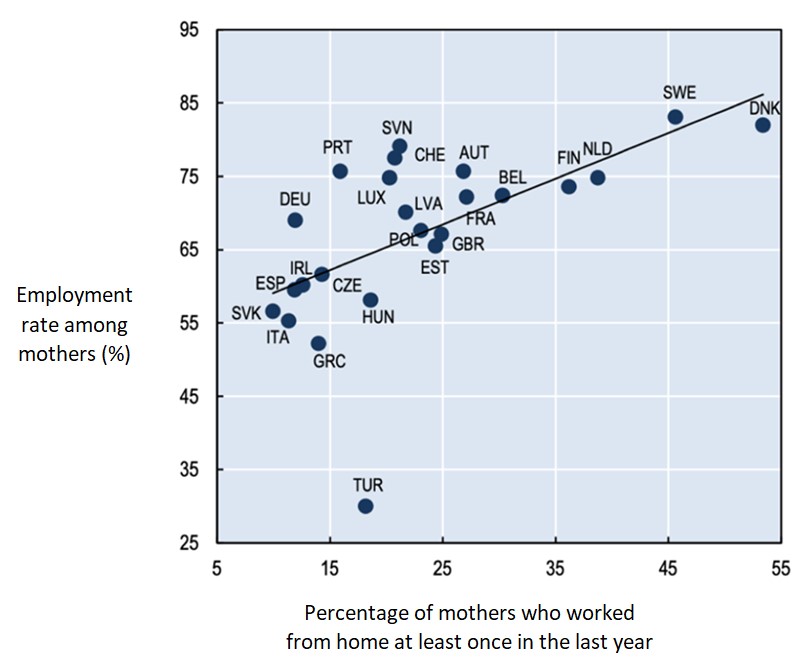

According to a 2017 OECD report, there is a positive association between the percentage of mothers working from home and their employment rate: the more that mothers are allowed to work from home, the higher the employment rate is (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The association between employment rate among mothers and percentage of mothers who have worked from home at least once

Source: OECD, 2017

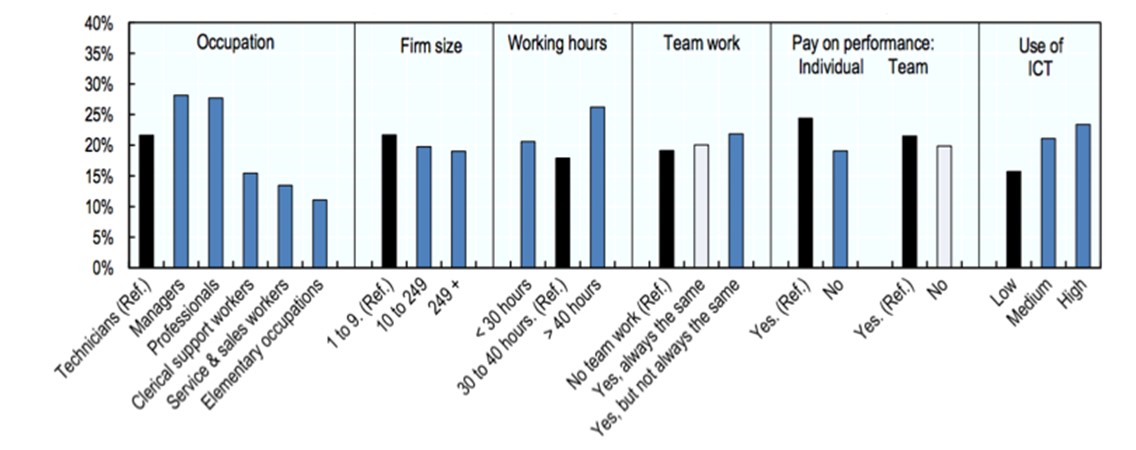

In addition, the OECD report presents several characteristics of those working from home: A higher percentage of managers and professionals work from home; a relatively high percentage of those working from home, work a large number of hours (over 40 per week); working from home usually involves the use of information and communications technology; workers are paid according to their output; and working from home is common in small businesses with up to nine employees (Figure 3 below).

Figure 3. Characteristics of employees working from home “at least sometimes” in the last 12 months (%)

Source: OECD, 2016

Pre-Coronavirus Work from Home in Israel

Data on working from home in Israel can be found in the Social Survey published by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) (2016) and in relevant surveys conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute (2018, 2019). According to CBS data, the percentage of women working from home in 2016 was 4.6%, compared with just 2.5% of men. In addition, the rate of those working from home was found to be particularly high among the self-employed, with less than 1% of salaried employees working from home, compared with approximately 18% of self-employed workers.

A survey carried out by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) in December 2019 (just a few months before the outbreak of the coronavirus) found that only 5% of salaried workers had the option of working from home, while 95% either had no such option or could do so only with special permission from their supervisor or in exceptional circumstances. Only 4% of workers with children reported that they could choose to work from home, compared with 7% of workers without children. On the other hand, 38% of workers with children could work from home with their supervisor’s permission or in exceptional circumstances, compared with 30% of workers without children (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Workers able to work from home as a partial or full alternative to working in the office, by parental status (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute survey 2019

The IDI survey also found that the option of working from home enhances the work-life balance among workers: 65% of those able to work from home feel they have a good balance between their work and their personal life, compared with just 43% of those who are unable to work from home at all. These findings are consistent with CBS data, according to which 71% of those working from home reported that they are satisfied with their work-life balance, compared with 58% of those who do not work from home.

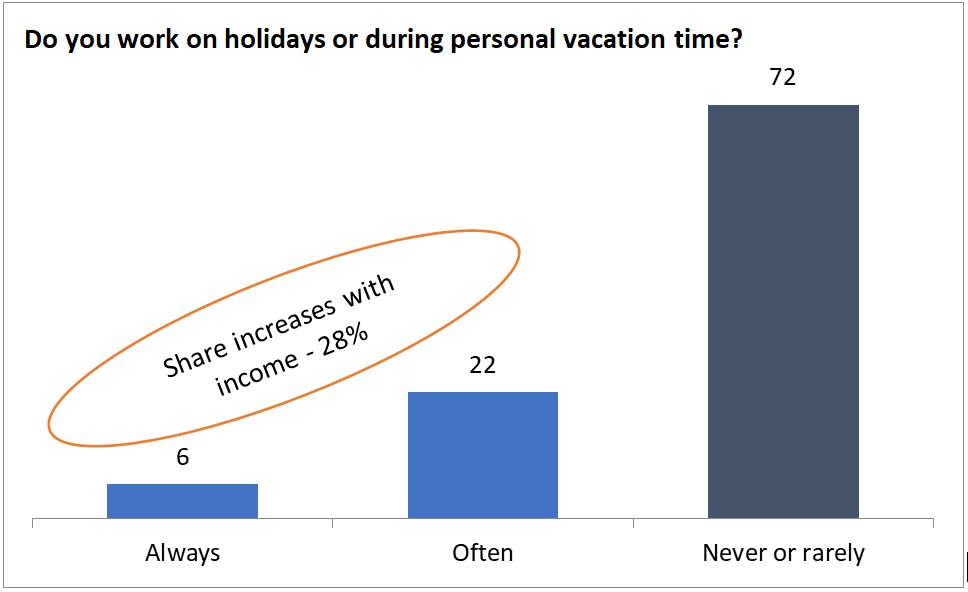

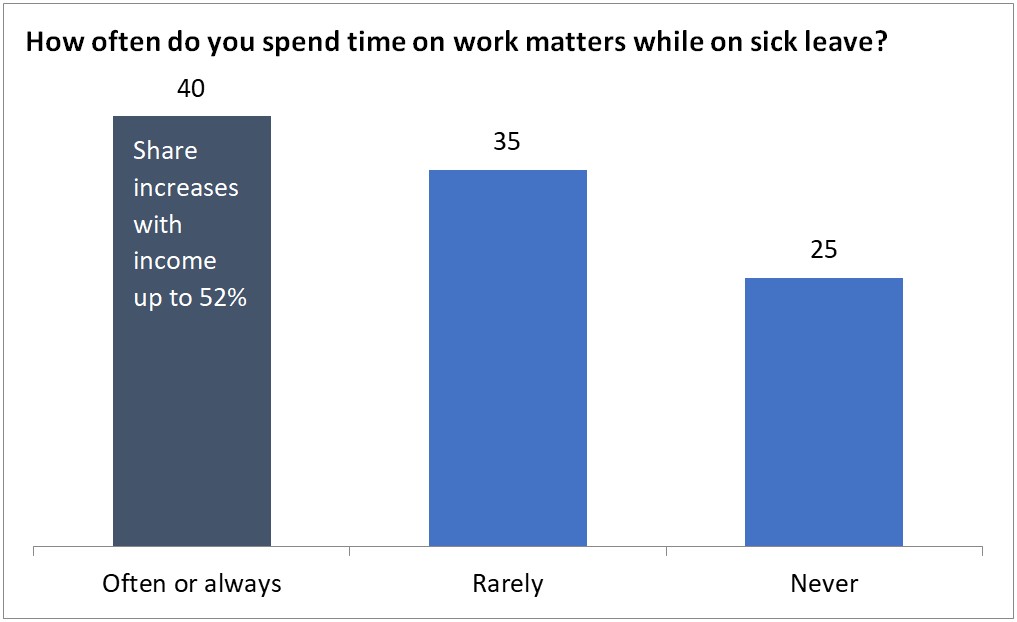

In addition, in the IDI survey 28% of workers reported that they work on holidays or during personal vacation time (Figure 5), and 40% – that they “often” or “always” work during sick leave (Figure 6). It should be noted that working from home during holidays, vacation time, or sick leave is positively associated with income.

Figure 5. Working from home during holidays or personal vacation time (in %)

Source: Kandel and Aviram-Nitzan, 2019

Figure 6. Working from home during sick leave (%)

Source: Kandel and Aviram-Nitzan, 2019

CBS (2016) data shows that the percentage of those who work from home while on sick leave is actually higher among employees who usually work at their workplace: 59% of these reported working during sick leave, compared with 54% of employees who usually work from home. In other words, it is possible that employees who work from home are more likely to allow themselves to rest when they are sick, than employees who work in the workplace. It should be noted that the percentage of women employed in the workplace who work during sick leave is higher than the equivalent percentage of men (64% versus 55%, respectively). However, among employees who work from home, this gap drops to 56% of women and 51% of men (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2016).

Working from Home during the Coronavirus—In Israel

The coronavirus crisis led to a sudden increase in working from home across a wide range of industries, occupations, and population groups. Surveys conducted in the midst of the crisis reveal the development of this phenomenon and its challenges, as large swathes of Israel’s businesses were forced by public health orders to close their doors or restrict their activities.

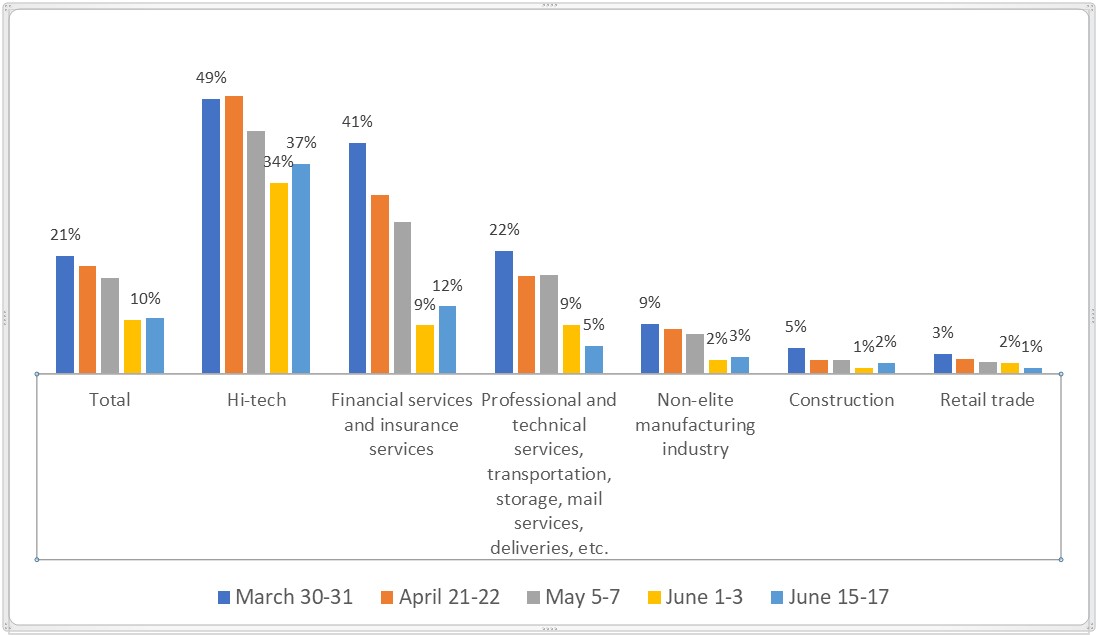

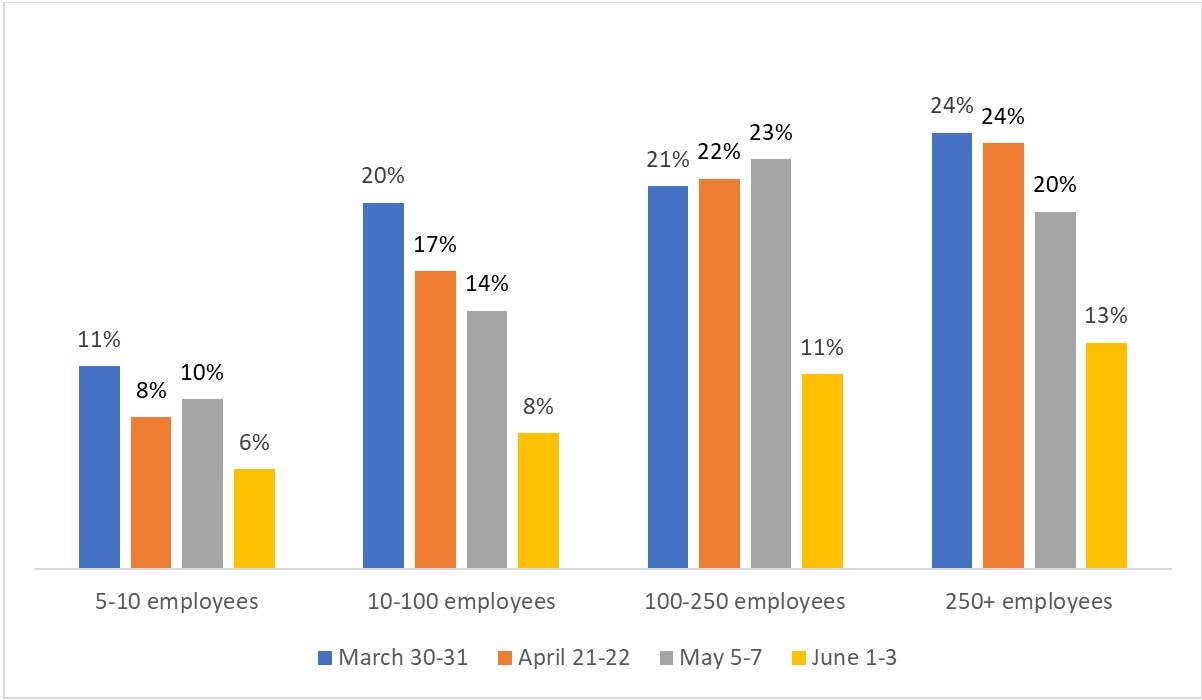

According to a CBS survey, the period of the epidemic has seen a rapid increase in the percentage of people working from home, which reached 10% in early June compared with around 4% in routine times. While working from home was not an option in certain industries (such as construction, and in large parts of the retail and personal service industries), in the hi-tech industry and the financial and insurance service industries a very high level of working from home can be discerned, at 49% and 41% respectively (Figure 7). Subsequently, as the restrictions were relaxed, the percentage of those working from home declined in all industries, with a sharp drop recorded in the financial and insurance service industries, from 41% to 9%. In hi-tech, the rate remained relatively high, standing at 34% at the beginning of June, and even growing by around 10% about two weeks later. Breaking down these changes by size of business (Figure 8) reveals that larger companies have a relatively high rate of employees working from home— reaching a peak of 23–24% in companies with more than 100 employees, compared with just 11% among companies employing 5–10 workers.

Figure 7. Working from home in businesses with at least 5 employees, March to mid-June 2020, by industry (%)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020

Figure 8. Working from home in businesses with at least 5 employees, March to mid-June 2020, by size of business (%)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020

In a special survey conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute at the end of March through the beginning of April 2020, following the outbreak of the coronavirus, 58% of salaried workers reported that they were working solely or partially from home. The percentage of men working from home was relatively high – at 32%, compared with 28% of women. A much higher percentage of the self-employed (60%) were found to be working from home than of salaried employees (30%), though most of the self-employed reported that they worked from home at least some of the time before the crisisThese findings are based on an Israel Democracy Institute survey conducted during the week before Passover (March 29 through April 2, 2020) among a representative sample of the working population in Israel..

Challenges of Working from Home

With the outbreak of the coronavirus, many people around the world were forced to change their work habits and switch to working from home. This period has served—in effect – as a pilot program among many employees in Israel, allowing us to learn about the characteristics of those working from home, the difficulties inherent in the current conditions, and the challenges facing workers and employers. These challenges include the work environment required at home, which affects employees’ efficiency and satisfaction; the need to develop suitable mechanisms for tracking efficiency and measuring output; adapting work from home for different populations and different industries and occupations; using technology and appropriate training to make work more accessible; and providing guidance on coping with the blurring of boundaries between work and personal life while working from home.

Employees who work from home fear that remote working will lead to becoming distanced and disconnected from their colleagues and will thus threaten their jobs. A U.S. study found that employees working part-time from home feel that their colleagues do not treat them equally. They fear that their colleagues talk about them behind their backs, make changes to projects without telling them in advance, lobby against them, and do not fight for their priorities. Similarly, they report negative impacts on productivity, costs, meeting deadlines, morale, and stress (Grenny and Maxfield, 2017).

In Israel, the feelings of people working from home in ordinary days were explored in the CBS’s Social Survey (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2016). The respondents expressed positive feelings toward their colleagues, but also greater fear for their jobs. Among employees working from home, 72% reported that their colleagues help them when needed (67% of men and 75% of women), compared with 69% among employees at the workplace.

People who work from home are more afraid of losing their jobs—about 50% of employees working from home worry about losing their jobs, compared with 40% of employees at the workplace. Figure 9 below presents the differences by gender: women are generally less worried and feel more secure in their jobs than men, with 47% of women who work from home worried about losing their jobs, compared with 57% of men.

Figure 9. Fear of losing their jobs, among workers from home and in the workplace, by gender, 2016 (%)

Source: Kandel and Aviram-Nitzan, 2019

Creating a comfortable working environment is one of the main challenges facing people working from home, including being able to work efficiently without distractions and without disruptions. In the survey mentioned above conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute, 40% of respondents working from home reported that they were able, “to a large or fairly large degree’ to carry out their work at home as efficiently as they did previously in the workplace (Figure 10). Among salaried workers, 42% said they were working as efficiently at home as they previously were in the workplace “to a large or fairly large degree”, 28% “to a moderate degree”, and 15% to a “fairly small or very small degree”.

It should be noted that employees view their efficiency differently than employers; 16% of employees working from home were unable to assess the efficiency of their work, compared with only 2% of self-employed workers. This finding reflects the need for employers and employees to formulate mechanisms for measuring outputs and assessing methods for working from home. In this context, the government—as the country’s largest employer—should ensure the development and implementation of mechanisms for measuring outputs of the public sector workers. If the public sector achieves these goals, this would represent a significant change towards efficient and improved services for the residents in Israel.

Figure 10. Efficiency of working from home versus in the workplace, by employment status (%)

Source: Flug, Aviram-Nitzan and Keidar, 2020

Another issue with regard to working from home which emerged during the corona crisis lockdown, was the challenge parents faced in combining work with childcare, due to the shutdown of the education system. Not surprisingly, workers without children reported being able to work more efficiently from home than did workers with children. Among workers without children, 55% reported that they were able to “a large or fairly large degree” to carry out their work at home as efficiently as in the workplace, compared with 35% of workers with children. Moreover, the younger the children, the lower the percentage of respondents reporting being able to work efficiently from home (around 33% of those with children aged six and below, compared with 40% of those with children above age six). It is worth noting that the percentage of employees with children who felt unable to assess the efficiency of their work from home (16%) was double that of employees without children (8%). Figure 11 below presents the percentage of workers with and without children who reported being able to work efficiently from home.

Figure 11. Perceived efficiency of working from home for parents by children’s age and for workers without children (%)

Source: Flug, Aviram-Nitzan and Keidar, 2020

Additional findings of the IDI survey on working from home reveal that during the crisis, the percentage of workers with an academic degree working from home was higher than those without: 47% and 13% respectively. That is, academic qualifications enhance employment security during a crisis, due to the greater possibility of working from home in relevant occupations. In regard to population groups, 33% of Jewish employees worked from home, compared with 19% of Arab employees.

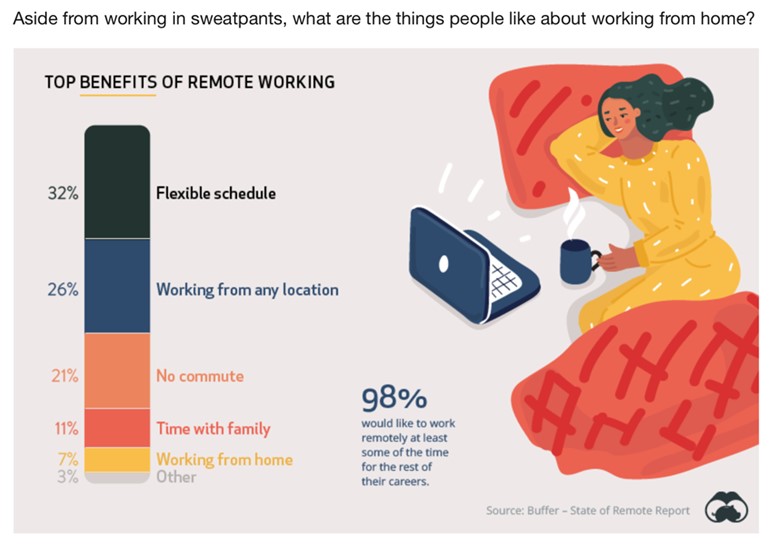

Despite the difficulties and challenges, it seems that the majority of the participants in the “great global experiment of working from home” were satisfied with this arrangement. A survey conducted at the beginning of June 2020 by the World Economic Forum (WEF) found that 98% of respondents wish to retain the option of remote working throughout their careers.

The survey examined how employees and employers feel about remote working, and mapped the main challenges and advantages associated with it.

Advantages for employees: The survey found that having a flexible schedule and being able to work from anywhere, and not having to commute, were the most frequently reported advantages of working from home.

Figure 12. Main benefits of working from home - employees’ perspective

Source: Routley, 2020

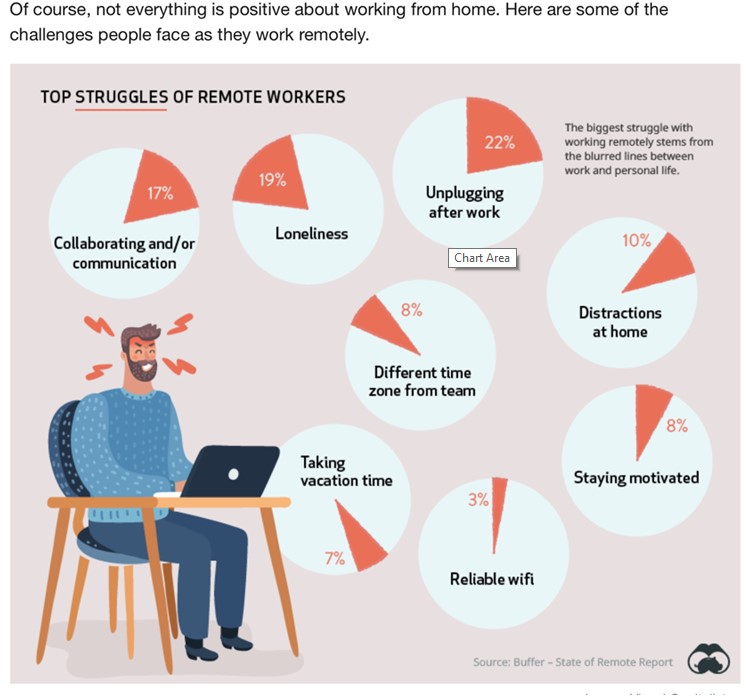

Disadvantages for employees include the blurring of the boundaries between work and personal life, disconnectedness from the working environment, and difficulties in separating work time from personal time given the lack of defined office hours and a differentiated location for working. For some people, loneliness and a lack of direct interpersonal communication also present a challenge (Figure 13). Additionally, one-third of respondents were concerned that it was impossible for their employer to appreciate the extent of their work efforts due to their disconnectedness.

Figure 13. Main challenges in working from home - employees’ perspective

Source: Routley, 2020

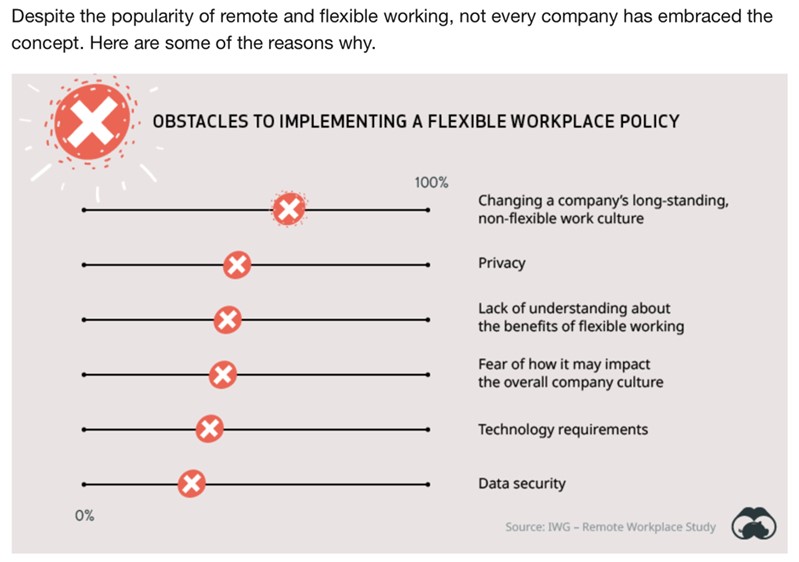

Barriers for companies: While there may be technical or security reasons for opposing remote working, the main barrier is resistance to change and the desire to maintain the status quo. Figure 14 below presents the main reasons cited by employers that do not permit remote working. More than 50% of companies that have not implemented remote or flexible working policies gave “long-standing non-flexible work culture” as a reason—in other words, they find it difficult to accept or lead change.

Figure 14. Main barriers to implementing work from home - companies’ perspectives

Source: Routley, 2020

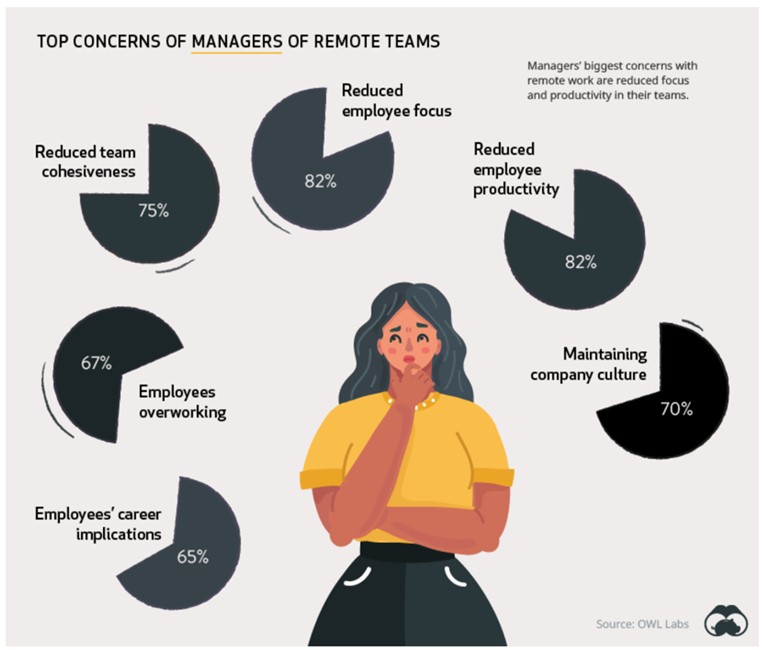

Opposition among managers stems from concerns that workers’ focus and productivity are reduced by working in informal settings, such as at home or in a café. In addition, , managers feel that when people are not working in the same physical location ,team cohesiveness and company culture are likely to suffer (Figure 15).

On the other hand, the savings in costs resulting from remote working can be an influential factor in the decision-making of many companies. Studies have found that a typical employer can save around $11,000 a year for each employee working remotely. Moreover, transitioning to virtual meetings also leads to significant reductions in costs (Routley, 2020).

Figure 15. Main concerns over working from home - managers’ perspectives

Source: Routley, 2020

Providing flexibility on the site in which people work is not just a means to enhance satisfaction among current employees. Companies that do not adopt flexible working practices are likely to find themselves at a disadvantage when trying to hire new talent, as almost two-thirds of candidates say that freedom to choose from where they work is a major consideration in selecting their employer.

The lockdown and the limitations on economic activity imposed to combat the coronavirus have highlighted the need for flexible working (and its advantages), particularly for parents: currently, 86% of parents want flexible working, compared with 46% before the outbreak.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The data on working from home at the height of the coronavirus crisis, when the economy was forced into lockdown, demonstrate the potential benefits of working from home in routine times as well. However, current conditions for doing so are not ideal, and efforts should be made to improve them. In order to encourage working from home in ordinary times, the government must act on several key issues:

• Formulate and institute clear rules for working from home, and adapt labor legislation accordingly (flexible working arrangements are widely spread and accepted in the world).

• Develop mechanisms for working at home in routine times, based on an understanding the needs and challenges experienced by both employers and employees. Following the mass experiment which the coronavirus provided, employers and the government should conduct an evaluation study on working from home, including real-time tracking of outputs, workers’ attitudes and feelings, challenges and advantages.

• Promote flexible working arrangements based on a better understanding of changes which must be made: adapting labor legislation and changing norms by establishing a clear mechanism for discussion and debate between employees and employers with regard to working arrangements.

• Upgrade Israel’s internet infrastructure to high-speed broadband (largely a regulatory issue; the emphasis on competition over pricing in the government’s communications reforms has come at the expense of investment in the needed infrastructure).

• Provide easy access to training programs and courses both to workers and managers on time management and working from home and on how to use the digital tools necessary for remote working. This can be done via the community center network, the education system, higher education and vocational training institutions, as well as by training on-site in the workplace with government subsidies for the training.

• Provide financial assistance for businesses (mainly small and medium-sized) to invest in making the necessary adaptations for remote working (information security, communications systems, remote access, and so on) by subsidizing at least 30% of the cost. This assistance may be provided through tax benefits or direct reimbursements.

• Develop methods for tracking and assessing employee performance and outputs when working from home. As the country’s largest employer, the government should ensure that mechanisms are in place for evaluating the output of public sector employees working from home. If successful, this will be a significant change that will help upgrade the efficiency of the entire public sector and improve services to citizens. (It can be assumed that the business sector will find ways to do this even without government assistance.)

• Help vulnerable populations benefit from the possibility of working from home, by ensuring access to computers, internet connectivity, and other measures.

With the relaxing of limitations on economic activity, decision-makers in government and in the private sector now have the opportunity to lead the way towards a major change in Israel’s work culture, which has already begun, and institutionalize working from home—at least for some days a week—as the new norm for millions of workers.

References

Arntz, Melanie, Ben Yahmed Sarra, and Francesco Berlingieri. “Working from home: Heterogeneous effects on hours worked and wages.” ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper 19-015 (2019).

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying. “Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130, no. 1 (2015): 165–218.

Central Bureau of Statistics. Social Survey. 2016. [Hebrew].

Civil Service Commission website. “Pilot to recognize additional worked from home to continue.” January 1, 2020. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/news/working-from-home. [Hebrew].

Ecotraders. Reducing use of private cars in the public sector. Report for the Ministry of Environmental Protection (2018). [Hebrew].

Eurostat website data. (2020).

Flug, Karnit, Daphna Aviram-Nitzan, and Yarden Keidar. Impact of the coronavirus on self-employed and salaried workers. Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute (2020). [Hebrew].

Grenny, Joseph, and David Maxfield. “A study of 1,100 employees found that remote workers feel shunned and left out.” Harvard Business Review (2017).

Kandel, Eugene, and Daphna Aviram-Nitzan. Public opinion poll: Work-life balance—Flexibility in work location and work hours, and preparedness for expected changes in the labor market (Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute, 2019). [Hebrew].

Mas, Alexandre, and Amanda Pallais. “Valuing alternative work arrangements.” American Economic Review 107, no. 12 (2017): 3722–3759.

Ministry of Finance. Report of the Commissioner of Wages. 2018. [Hebrew].

Ministry of Justice. Annual report of the Israel Patent Office. 2018. [Hebrew].

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Going digital: The future of work for women. (2017). https://www.oecd.org/employment/Going-Digital-the-Future-of-Work-for-Women.pdf.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Be Flexible! Background brief on how workplace flexibility can help European employees to balance work and family. (2016). https://www.oecd.org/els/family/Be-Flexible-Backgrounder-Workplace-Flexibility.pdf.

Routley, Nick. “6 charts that show what employers and employees really think about remote working.” (2020). World Economic Forum website, June 3, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/coronavirus-covid19-remote-working-office-employees-employers/.

Sentz, Kristen. “How companies benefit when employees work remotely.” Harvard Business School website, July 29, 2019. www.hbswk.hbs.edu/item/how-companies-benefit-when-employees-work-remotely.