Transitions Between Religious Groups among Israeli Jews: Abstract

This study provides first-ever reliable estimate of the rate and scope of transitions into and out of the ultra-Orthodox community; an analysis made possible thanks to innovative methodology and a rich dataset.

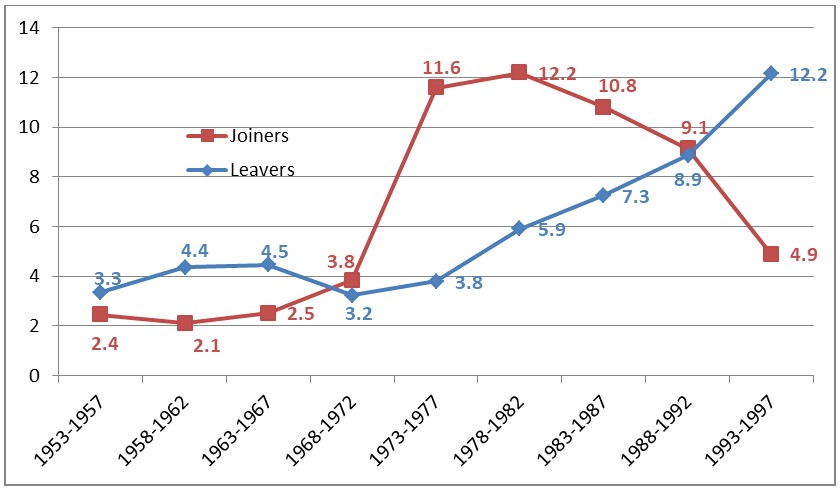

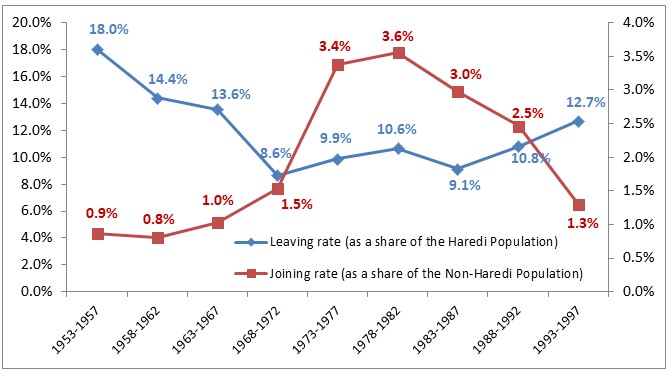

The findings reveal that the percentage of those (ages 20-64) leaving the ultra-Orthodox sector (cited here as “leavers”) is approximately 13.3%, while the rate of transition into ultra-Orthodoxy (“joiners”) among the national-religious and secular populations is 4.9% and 1.0%, respectively. However, in absolute terms, the overall number of individuals aged 20–64 who have joined the ultra-Orthodox sector (but who did not grow up in an ultra-Orthodox household—what is termed as baalei tshuva) is approximately 59,500, while approximately 53,400 who grew up in ultra-Orthodox households, left the ultra-Orthodox sector. At the same time, among younger age groups, we see a sharp rise in the number of “leavers”, alongside a steep decline in the number of “joiners.” Thus, among individuals born between 1993 and 1997, there is a large gap between the two groups (numbering about around 7,300) in favor of the “leavers.”

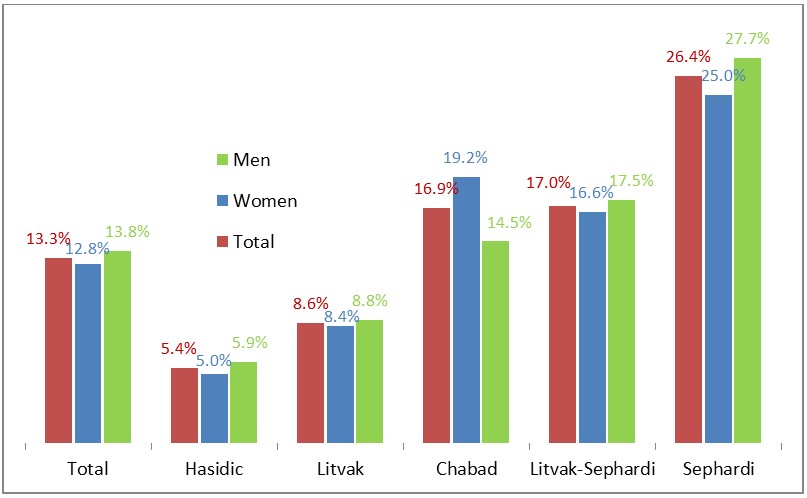

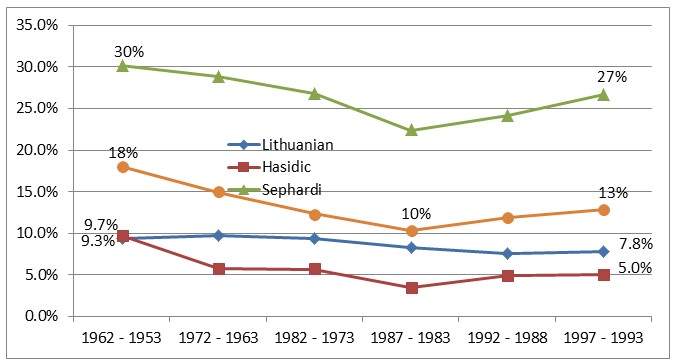

The Ultra-Orthodox community is divided into several religious movements, factions or denominations. Only 5.4% in the Hasidic ultra-Orthodox faction, as compared with 8.6% of the “Lithuanian” faction and 26.4% of Sephardim have left ultra-Orthodoxy. Rates among women are slightly lower than those among men. Those leaving the Sephardic faction constitute around 57% of all those leaving the ultra-Orthodox sector.

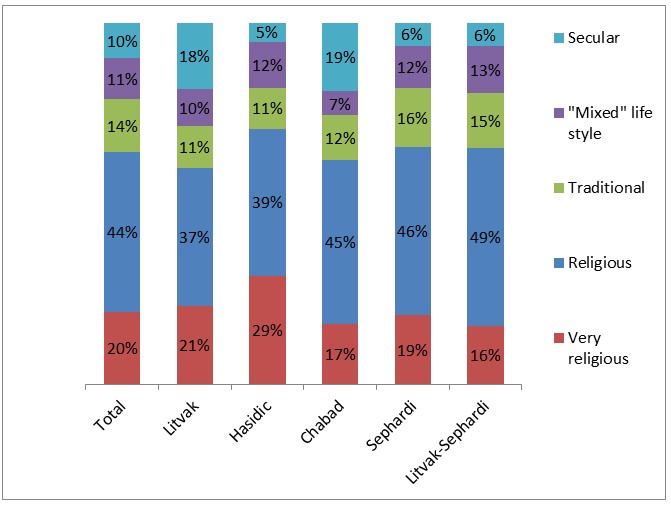

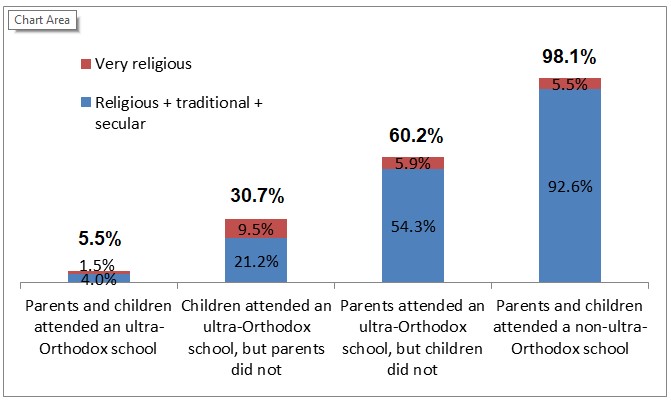

64% of the “leavers” now define themselves as religious or very religious. A look at their educational background—that is, the type of high school they attended - (ultra-Orthodox or not), reveals that about 28% of them left ultra-Orthodoxy while they were still minors. Only 1.8% of those who grew up in a secular or National Religious home define themselves as ultra-Orthodox in adulthood.

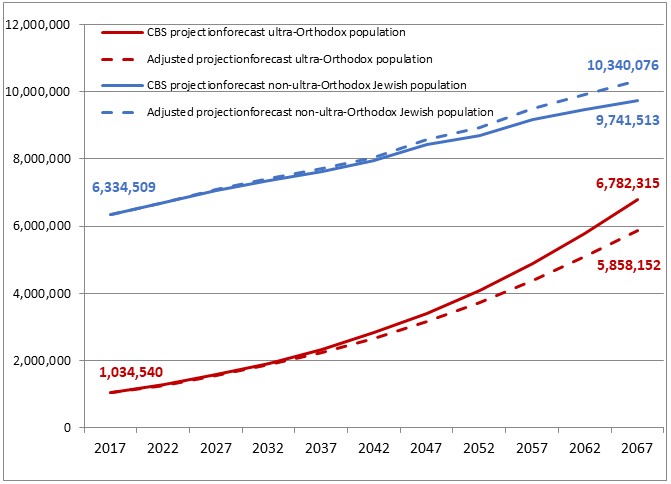

Adjusting for the transitions between the different sectors, our projection for the size of the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel in 2067 is lower by around 925,000 individuals (that is, by some 14%) than the projection of the Central Bureau of Statistics (around 5.86 million compared with around 6.78 million, respectively). Accordingly, the adjusted projection for the size of the rest of the Jewish population in 2067 is higher by about 600,000 (that is, some 6%) than the CBS projection (around 10.34 million compared with around 9.74 million, respectively).

According to our standardized projections, the total number expected to leave the ultra-Orthodox sector between 2017 and 2067 is approximately 420,000. Over the same period, some 176,000 people are expected to join the ultra-Orthodox sector.

The findings of this study (and others) reveal a high correlation between the characteristics of the “leavers” and the “joiners,” (particularly in the Sephardi community: In the 19–25 age group, at least 28% of the “leavers” are children of parents who made a transition in the opposite direction and became ultra-Orthodox (“ba’alei teshuva”).

Some 57% of the “leavers” belong to the Sephardi faction (which constitutes only around 33% of the entire ultra-Orthodox population), and similarly, approximately 58% of the “joiners” are of Sephardi origin. The lowest rates of leaving ultra-Orthodoxy and the highest rates of joining the ultra-Orthodox community, are found among those born during the 1970s, who were in their twenties during the “golden age” of Israeli ultra-Orthodoxy (in economic and political terms, and particularly of the Sephardi faction) during the 1990s and at the beginning of the 2000s, which came to an end with the sharp cuts to subsidies in 2003.

Some 64% of the “leavers” now define themselves as religious or very religious. Yet interestingly, many of those who had an ultra-Orthodox education and currently define themselves as very religious (rather than as ultra-Orthodox), send their children to ultra-Orthodox schools. This may be the case because some did not originally define themselves as ultra-Orthodox, even though they received an ultra-Orthodox education; or alternatively, it might be that some of them still live in ultra-Orthodox communities though not fully identifying with the ultra-Orthodox way of life, and thus prefer to define themselves as ”very religious”. In this context, it is worth noting that only around 20% of the “leavers” now define themselves as “very religious”, and the majority of those who now define themselves as “religious”, send their children to educational institutions that are not ultra-Orthodox.

Overall, these findings indicate that it is highly probable that many of those who have left the ultra-Orthodox sector made the reverse journey at some time in the past, when they joined the sector, or (most commonly) are the children of parents who became ultra-Orthodox. This is very likely to characterize mainly among the Sephardi faction, which is also characterized by the highest rates of leaving ultra-Orthodoxy. The upshot is that the percentage of “leavers” within the ultra-Orthodox mainstream (not including the newly ultra-Orthodox) is likely much lower than the overall percentage. On the other hand, high rates of leaving ultra-Orthodoxy are also characteristic of veteran Sephardi ultra-Orthodox familiesOur investigations have found that even among veteran ultra-Orthodox families in the Sephardi stream, the leaving rate is around 20%—much higher than the equivalent rates in the Hasidic and Lithuanian streams.. In any case, the data show that the overall rate of leaving ultra-Orthodoxy in the sector as a whole, is on the rise in the younger age groups (those born between 1993 and 1997) , with the rate among them being ten times as high as the rate joining the ultra-Orthodox sector. Based on these trends, we are likely to see a significant rise in the number of young people leaving the ultra-Orthodox sector in the coming years, with their current number standing at some 3,000 a year.

According to our projections, the overall number expected to leave the ultra-Orthodox sector between 2017 and 2067 is approximately 420,000—around 40,000 of them in the coming decade, and an additional 55,000 in the decade after that. These will be added to some 35,000 young people (aged 20–39) who have left the sector in the recent years and are making their way in Israeli society and in the labor market.

We hope that the findings of this study will make it possible for government agencies to take into account the unique characteristics of this population in the future, in order to formulate policies that will facilitate its optimal integration.

In this context, an important (and surprising) finding, which goes against what has been conventional wisdom until now, is the fact that the leaving rate among women is only slightly lower than that among men. While most of the younger “leavers” are men, among the older age groups the gap is much smaller, indicating that women leave the ultra-Orthodox sector at a later age than men. This may stem from the fact that the price of leaving is higher for women, and the reactions of the community much harsher (Horowitz 2018). As a result, women might prefer to conceal and delay taking steps to leave the sector. This finding highlights the need to look more closely at the population of women “leavers”, who need support and direction no less than men, (and perhaps even more), and yet the agencies that could provide help to them seem to be less familiar with their challenges. On the other side of the equation, the number of “joiners” constitute a significant portion(about 15%) of the ultra-Orthodox sector . This is a group with very specific characteristics and needs, encountering significant difficulties in integrating into the ultra-Orthodox community, and sometimes experiencing the alienation of the community’s main core. As noted by Malchi (2016), this group “faces difficult choices and challenges as to its social standing, complicated spousal relationships, and with regard to their children’s education, as well as the question of its integration within the general ultra-Orthodox population, which can often be ambivalent toward ba’alei teshuva, even years after their transition to ultra-Orthodoxy.”

This population differs from the veteran ultra-Orthodox population in various respects, including in its geographical distribution, level of formal education, access to public resources and funding, and with less access to community support. It is important that policymakers be provided with accessible information on the particular needs of this group, as well as with data on its size and characteristics, and take this information into account will be in the formulation of policy for the ultra-Orthodox sector.

Figure 3. Numbers of people who have left the ultra-Orthodox sector compared to the number who joined it, by year of birth, 2017 (ages 20–64; in thousands)

Figure 4. % of People who left the ultra-Orthodox sector, by faction and gender, 2017 (ages 20–64)

Figure 7. Level of current religious observance among people who left the Haredi Sector, by ultra-Orthodox faction and current religiosity, 2017 (ages 20–64; %)

Figure 9. Rates of leaving the ultra-Orthodox sector, by year of birth and ultra-Orthodox faction 2017 (ages 20–64)

Figure 12. Leaving and joining rates in the ultra-Orthodox sector, by year of birth, 2018 (ages 20–64; %)

Figure 16. Share of Young adults (ages 19–25) not defining themselves as ultra-Orthodox, by type of Education they and their parents received at youth, , 2014–2019)

Demographic Projections Adjusted for Leaving and Joining Rates in the Ultra-Orthodox Sector

The findings on the relatively high leaving rates in the ultra-Orthodox sector compared with low joining rates raise questions regarding the future impact of these transitions on the size and demographic composition of the Jewish population in Israel. Though we cannot know for certain what these rates will be in the future, we can reasonably and cautiously use the current trends as the basis for more updated demographic projections, which take into account the transitions between the different sectors.

Figure 22. Demographic projections adjusted for leaving and joining rates in the ultra-Orthodox sector versus CBS projections, 2017–2067