Israel Heads Toward Its Fourth Elections

After failing to meet the December 22 deadline for passing a budget, Israel is headed towards a once unfathomable fourth election in less than two years. The results of the last three elections in 2019-2020 did not dispel the political turmoil - we are about to see if the results from the fourth elections in 2021 will be any different.

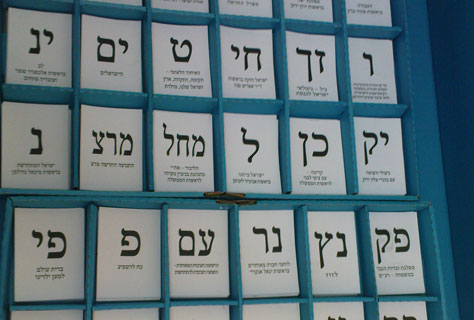

Flash 90

After failing to meet the December 22 deadline for passing a budget, Israel's Knesset has now dispersed, and the country is headed towards a once unfathomable fourth election in less than two years. It should now be clear that the country will be stuck in this seemingly intractable situation of recurring elections until one of two things occur. Either a government will eventually be formed without Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, or he will eventually achieve a majority in the Knesset that allows the passage of laws or regulations that stall, or completely halt, his trial on corruption charges. The results of the last three elections in 2019-2020 did not allow for either of these scenarios. We are about to see if the results from the fourth elections in 2021 will be any different.

How Did We Get Here?

Netanyahu's refusal to advance and pass the 2021 budget can only be described as a signing of a death sentence for the government formed just last April. Israel last passed a budget in 2018, and since the multiple elections of the past two years have ended inconclusively, no government had been in place to pass a new one. This means that the government is running monthly on one-twelfth of the 2018 budget – long before the Covid crisis and its devastating economic consequences entered our lives.

By law, the government was supposed to pass the 2020 budget within 95 days of its formation in May. This meant that it had until August 25 to do so, or the Knesset would automatically disperse. The coalition agreement signed between Likud and Blue and White also stipulated that the 2021 budget would pass the Knesset at the same time. This was intended to provide stability after a long period without an approved budget and take into account that most of 2020 was no longer relevant with only four months left in the year.. Politically, this meant that once the two-year budget passed, Benny Gantz was almost sure to become prime minister – either when the rotation date arrived in November 2021, or if the government fell for any reason besides the budget, and then he would serve in that position until a new government was formed after an election.

As August approached, Netanyahu realized that the budget deadline offered a last “exit ramp” from the rotation agreement, and he reneged on his commitment to pass the 2021 budget. He also used the opportunity to push for changes in the legal system, despite his conflict of interest and his pledge to the Supreme Court that as a defendant in a corruption trial, he would recuse himself from these matters. At the last moment, a compromise was reached in the summer, setting December 23 as the new deadline for passing the budget. Yet, Netanyahu stood firm and refused to budge on the idea of passing the 2021 budget before March.

An additional last-minute compromise to extend the budget deadline was crafted as the December deadline approached, but rebel backbenchers in both Blue and White and Likud voted against the initiative, burying any chance of staving off the election.

What Happens Next?

In the upcoming election, we can expect to see an even worse stalemate than what we have witnessed over the past two years, with no budget, no appointments, and a cabinet table shared by campaign rivals. All this while unemployment skyrockets, the pandemic continues, and Israel enters into a third national lockdown.

To make matters worse, all governmental decisions on how to deal with the pandemic will be accused of being driven by political motives, as each side panders to its base with an eye towards the election. This will aggravate an already fragile situation, in which during the second lockdown back in September and October, 55 percent of Israelis already believed that public health decisions were politically motivated.

Who Are the Players?

Netanyahu's calculations in setting the course for elections are complicated. Most polls still show his Likud party with the best chance of forming the next government, yet Israel Democracy Institute data from November shows that only 37 percent of Israelis trust Netanyahu’s management of the coronavirus crisis (though this is up from the all-time low of 27 percent in September.) Even among the ultra-Orthodox, his staunchest supporters outside the party, 62 percent say they have little or no trust in Netanyahu's handling of the pandemic.

At the same time, in the March election, Netanyahu will see two serious challengers from the right. Naftali Bennett, Netanyahu's former chief of staff and a minister in his governments, has seen his popularity soar, as he has rebranded himself as a Covid expert focused on getting the Israeli economy moving again.

In addition, Gideon Sa'ar – another former minister, cabinet secretary to Netanyahu, and one of the most popular politicians in the Likud – has now formed his own center-right party with the stated intention of unseating Netanyahu. Sa'ar has already been joined by Ze'ev Elkin, a senior Likud minister previously considered close to Netanyahu, and their new party is gaining steam. Most significantly, in some polls, Sa'ar is almost tied with Netanyahu, when respondents are asked who is most fit to serve as prime minister.

The reality on the center-left is even more complicated. The once-mighty Blue and White party that came close to forming a government after the last round of elections, is now polling at only five Knesset seats. It is unclear if Yair Lapid's Yesh Atid party will be able to fill the void, or if another party representing Israel's upper-middle class will be joining the fray. Finally, the mostly Arab Israeli Joint List has let political infighting threaten progress made over the past year to better capitalize on Arab political power, and the faction may split - with some of the parties who now make up the list not passing the 3.25 percent electoral threshold.

An Election Like No Other

The election of 2021 will be like no other Israel has experienced. In addition to the constitutional crisis that has led us to this previously inconceivable reality, the very way the government will run and the election process will be completely unique. This is because instead of instituting well-thought-out electoral reforms that would actually stabilize the political system, such as those that IDI has been advocating for, Israel's leaders have chosen patchwork changes to quasi-constitutional Basic Laws, focused narrowly on advancing their momentarily personal interests.

In the past, when governments lost their Knesset majorities, the sitting prime ministers found themselves in an odd position. While they were usually unable to pass laws in parliament, and legal precedent limited some of their powers, such as the appointment of senior officials, they were in some ways more politically powerful than in “routine” times. For instance, the prime minister could fire ministers as he desired and appoint other sitting members of Knesset as cabinet members without Knesset approval. This reality usually led ministers from parties not aligned with the sitting prime minister to either be fired or quit the cabinet during election campaigns.

The new laws put in place when the present government was sworn in upended these rules and norms. Now, there are essentially two heads of the government – Netanyahu and Gantz – each responsible for the ministers reporting to them. This means that Netanyahu cannot fire the ministers affiliated with Gantz (Blue and White, and Labor), and they are likely to remain in their key cabinet posts through the election and until the moment a new government is eventually sworn in. The political posturing we have seen throughout this government's tenure will seem like nothing at all, when compared to what Israel will endure in the months ahead.

On top of all of this, these elections will be Israel's first during a full-blown pandemic. The country did have a number of people in quarantine during the March 2020 election, resulting in a few specially designated voting stations. That, however, was a very different situation from today's reality of close to 30,000 active cases and thousands more in legally mandated quarantine. Israel is unlikely to follow in the U.S.'s footsteps and institute widespread mail-in or absentee balloting. There will, however, likely be the need for additional voting places and personnel – what is sure to increase the budget for already costly elections that in routine times include publicly funded campaigns and a national day off on Election Day.

Conclusion

Like so much that has occurred in Israel over the past two years, this latest election has all sides scrambling to understand its repercussions, with many questions left unanswered.

After the election, will Netanyahu finally succeed in forming the coalition he has sought for so long and which will allow him to escape his legal woes? Will Israel find itself stuck in this political loop, where neither side can declare victory and the country keeps going back to the ballot box? Or, will a fourth election with still unknown political players and parties actually create a new reality, in which for the first time since 2009 someone besides Netanyahu occupies the Prime Minister's Office?

The article was published on the Jewish Funders Network.