Working from Home: Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis

Numbers working from home skyrocketed with the outbreak of the pandemic mainly among white-collar workers, workers with an academic degree, and high-salary workers

Shutterstock

Before COVID-19, around 9% of workers in Israel worked from home, for all or some of their work hours, according to a survey carried out by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) in July 2020.

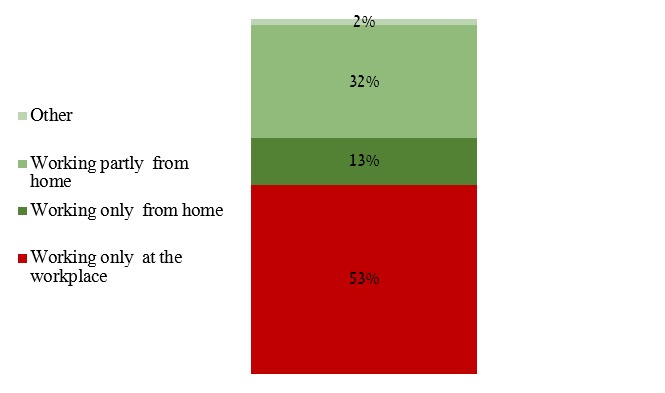

Numbers working from home skyrocketed with the outbreak of the pandemic. A series of IDI surveys conducted since then among employed Israelis (salaried employees and self-employed workers who were working when the crisis began), revealed that the percentage of those working from home at the end of March 2020, when the first lockdown was imposed, had jumped to 55%, and then declined to around 43% in July 2020, when the lockdown was eased, though social distancing restrictions remained in place. This latter figure is similar to the figures in the interim periods between lockdowns since that time. The findings of a December survey (conducted just before the third lockdown) reinforce this data, showing that the percentage of those working from home during the second week of December 2020 stood at 45%.Survey from end of March/beginning of April 2020 [Hebrew]: https://www.idi.org.il/blogs/special-economic-survey/march-april-2020/31797. Survey from July 2020 [Hebrew]: https://www.idi.org.il/media/14897/economic-poll.pdf This figure comprised around 13% of workers (both salaried employees and self-employed) who were working only from home (including 5% who worked only from home before the crisis) and 32% who were working partly from home and partly at the workplace (including some 7% who had worked some of the time from home beforehand) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Employed Israelis (salaried and self-employed) by Place of Work: December 2020

Source: Israel Democracy Institute, December 2020

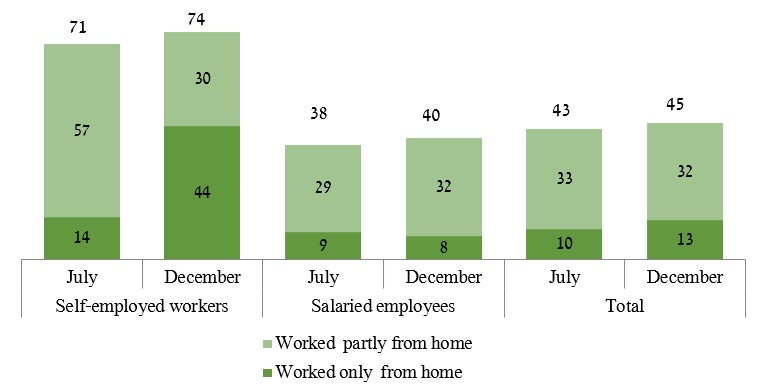

The percentage of self-employed workers working from home at the beginning of December (around 74%, including 44% working only from home) was significantly higher than that among salaried employees (40%, including 8% working only from home). In July as well, some 70% of self-employed workers were working from home, though a much smaller share-- just 14%-- were working only from home (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Employed Israelis Working both from Home and the Workplace by Employment Status: July and December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute surveys, July and December 2020

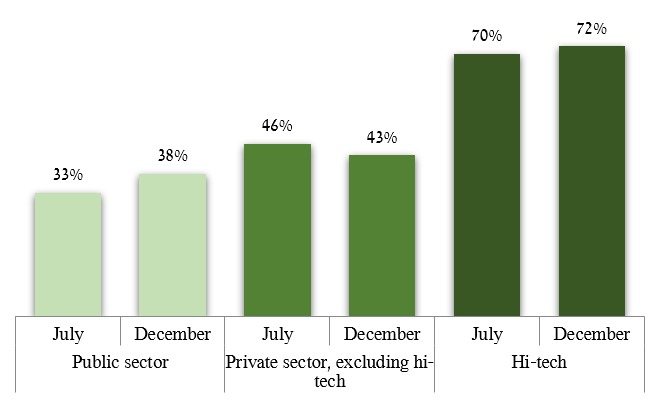

The percentage of those working from home in the hi-tech industry in July and in early December 2020, was significantly higher (70%-72%) than in the rest of the private sector (43%–46%) and in the public sector (33%–38%). While the private sector (not including hi-tech) saw a slight drop in working from home between July and December, the figures for the public sector rose over this period (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Employed Israelis Working from Home (only or partly) by Employment Sector: July and December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute surveys, July and December 2020

The Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) periodically examines the percentage of workers working from home during the pandemic. However, the CBS data only includes salaried employees who reported working from home on a specific day (the day on which the survey was conducted), while the IDI surveys include both salaried and self-employed workers who reported working from home either only or partly “at the present time.”

Despite these differences, the CBS data indicate that over the summer months (the period between the first and second lockdowns), an average of 10% of salaried workers were working from home: a figure similar to the 9% who reported working exclusively from home in the mid-July IDI survey and to the corresponding 8.5% in the December 2020 IDI survey.

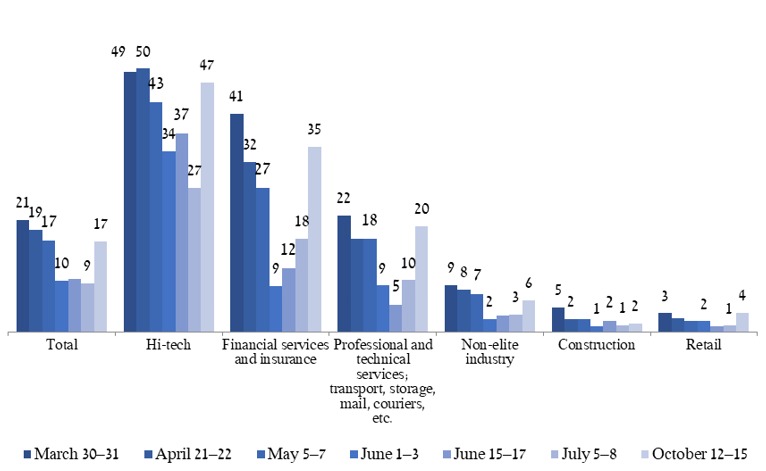

The CBS surveys reveal that the prevalence of working from home among salaried employees differed by economic branches. At the height of the first lockdown (end of March 2020), approximately one-half of salaried employees in the hi-tech sector and 41% of salaried employees in the financial services and insurance branches were working from home, in contrast with much lower percentages of workers in construction, retail, and personal services. These gaps between sectors remained in place even as infection rates fell and restrictions were eased, in June and July 2020, when the percentages of those working from home declined in all industries: Hi-tech still had the highest share of workers from home, at around 34%, compared with just 1% or 2% in construction and in retail industries (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Work from Home among Workers in Businesses with 5 Employees or More, by Industrial Sector: March--July 2020 (%)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020

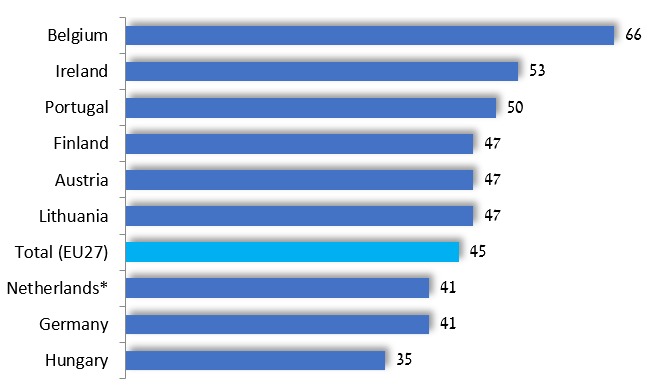

The rate of work from home in Israel and in EU countries is similar. When asked "Where did you work during the pandemic?" 45% of workers in EU countries answered that they worked from home (in June-July 2020), with relatively high rates in Belgium (66%), Ireland (53%) and Portugal (50%), as compared with 41% in the Netherlands and Germany and 35% in Hungary (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Workers Working from Home in the EU, June and July 2020A special Eurofound survey conducted in EU countries in July, when the economy began to open up after the first wave of the corona. The graph does not include countries where the level of data reliability was found to be low (%)

Source: Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data

Though it is commonly believed that remote working, which enables access to distant workplaces, enhances employment opportunities for individuals from specific population groups (residents of the periphery, people with physical disabilities, parents of young children, and others), it appears that in the course of the pandemic, disadvantaged populations have benefited less from working from home.

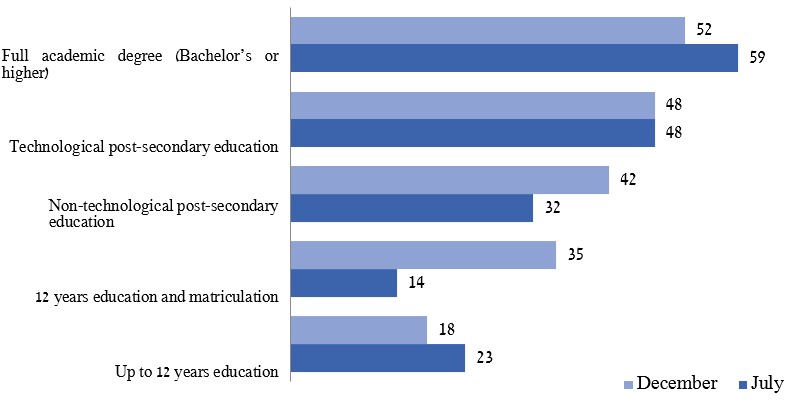

Evidence for this can be found in the December 2020 IDI survey, according to which working from home was associated with level of education, rising from 18% among workers with the lowest level of education (12 years of education or less); to 35% among workers with 12 years of education and a matriculation certificate; 42% among workers with a non-technological post-secondary education,Such as teacher training institutions, nursing schools, non-technological vocational training, non-degree programs in academic settings, and more. up to about half of workers with a technological post-secondary education.Including practical engineers, technicians, electricians, QA workers, and so on.

The highest percentages of working from home were found among workers with an academic degree, at 52% (59% in July). These findings demonstrate that higher education (academic education and non-academic technological education) makes it possible to work in professions in which much of the work can be carried out remotely. Consequently, workers with an academic or technological education have enjoyed a higher level of job security, because they had the option of working from home during the crisis (see Figure 6).

In fact, the large increase in remote working during the pandemic was seen mainly among white-collar workers, workers with an academic degree, and high-salary workers. The nature of many of the jobs done by other workers requires being physically present in the workplace and does not make it possible to work from home; this, along with poor quality of internet infrastructure, makes remote working more difficult (Israel Democracy Institute, July 2020).

Figure 6. Work from Home by Level of Education: July and December 2020, (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute surveys, July and December 2020

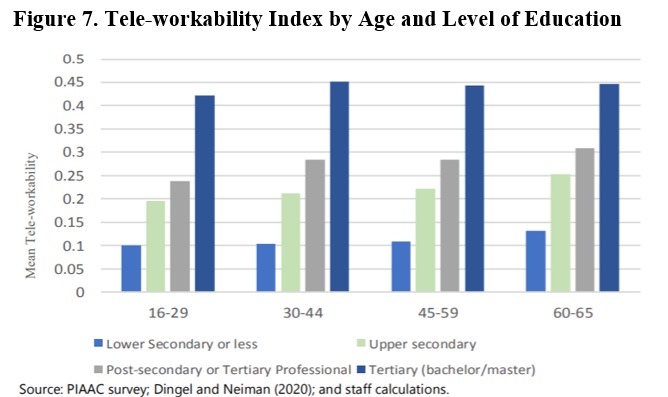

An International Monetary Fund study on Tele-workability in different countries also reveals that this possibility is associated with level of education, and only slightly with age (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Tele-workability Index by Age and Level of Education

Source: Brussevich, Dabla-Norris, and Khalid, 2020

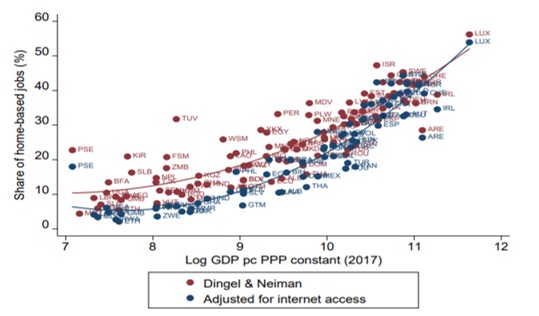

A study published in July 2020 found a positive association between working from home and GDP per-capita (Sanchez et al. 2020). The study shows that in countries with high GDP, 38% of jobs can be carried out remotely, as compared with 25% in countries with low to medium GDP. With regard to differences in internet access, the higher the percentage of workers without access to internet, the lower the percentage of those working from home (33.6% in countries with high GDP and 17.8% in countries with low to medium-level GDP). The data on Israel reveal a relatively high percentage of jobs that can be done remotely—over 40%- even after taking into account the percentage of workers with no internet access (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Share of home-based jobs vs GDP per Capita across countries

Source: Sanchez et al. 2020

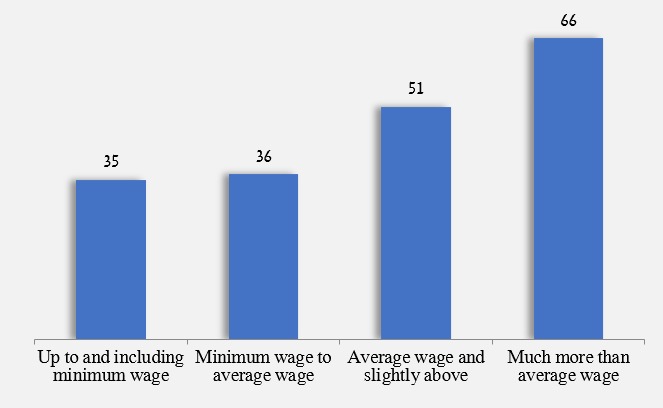

This finding was also corroborated by the results of IDI surveys conducted in July and December 2020, revealing that the percentage of those working from home increases with income. That is, there is a positive association between income level and the possibility of working from home. The most recent survey found that while 35% of low-income workers (earning up to and including minimum wage) were working from home, the corresponding figure among high-income workers (earning much more than the average wage) was 66% (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Work from Home by Level of Income: December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute survey, December 2020

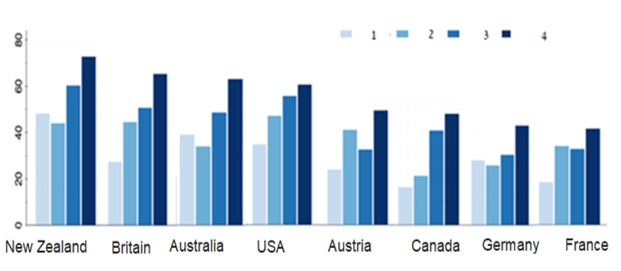

An OECD survey conducted in April in selected countries also shows that, similar to the findings of the survey in Israel, in these countries there is a positive association between the rate of work from home and the level of income. Figure 10 shows the increase in the rate of work from home with the increase in income quartiles.

Figure 10: Working from Home by Income Quartiles in Selected Countries, (%)

Source: Galasso and Foucault, 2020

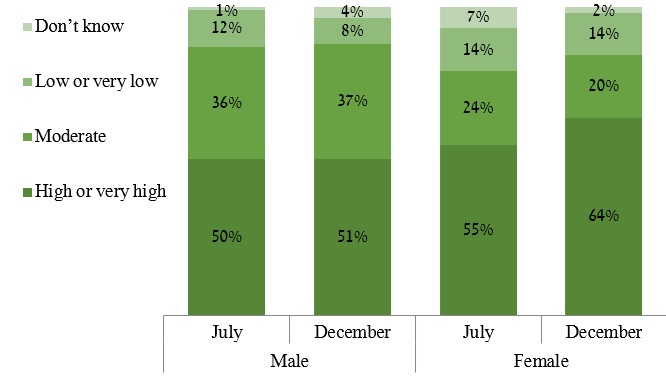

Access to a suitable working environment is one of the main challenges in working from home, including being able to work efficiently and without distractions or interruptions. In the July 2020 IDI survey, 52% of respondents (55% of women and 50% of men), working from home reported that the efficiency of their work at home was at a high or very high level, as compared to at the workplace, while 31% reported that their efficiency was moderate, and 13%- that it was low or very low. The December 2020 findings were similar, though the gap between men and women increased, with 64% of women reporting high or very high efficiency of their work at home,, compared with 51% of men (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Efficiency of Work from Home as Compared with at the Workplace, by Gender: July and December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute survey, December 2020

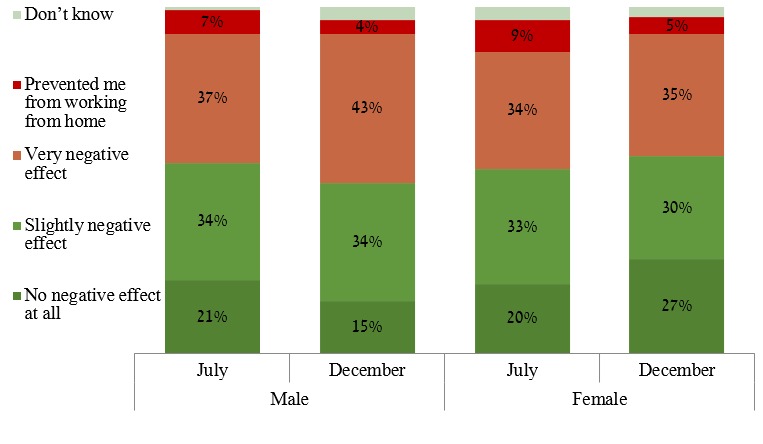

The responses to the July and December 2020 IDI surveys support the basic assumption that the presence of children in the home during the pandemic has had a negative effect of the efficiency of working from home: In December, 81% of men and 70% of women reported that their work at home had suffered as a result of the having children around (76% on average), a finding similar to in the July survey (77% on average). In terms of the degree of the negative effect, 35% of women reported that children's presence had a very negative effect on their work (34% in July), compared with 43% of men (37% in July); around 30% of women reported an only a slightly negative effect, while 5% of women reported that children's presence prevented them from working at all (9% in July) (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Negative Effect of Having Children at Home on Efficiency of Work from Home, by Gender: July and December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute survey, December 2020

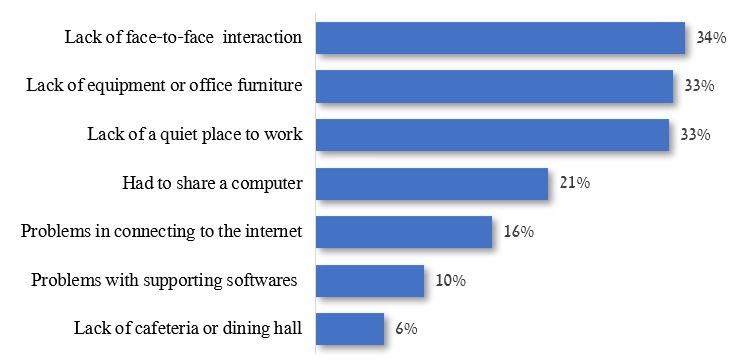

Other challenges encountered in working from home include the need for access to basic physical conditions, such as a desk, suitable chair, computer, appropriate lighting conditions, a quiet place to work, and so on. In the July 2020 IDI survey, 74% of workers reported having experienced difficulties in this regard, 34% reported suffering from the lack of face-to-face interaction; 33% reported a lack of equipment office or furniture, or a lack of a quiet workspace. Around one-fifth of workers had to share a computer with other members of their household, and 16% encountered difficulties in connecting to the internet (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Workers Reporting Difficulties in Working from Home, by Type of Difficulty: July 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute survey, July 2020

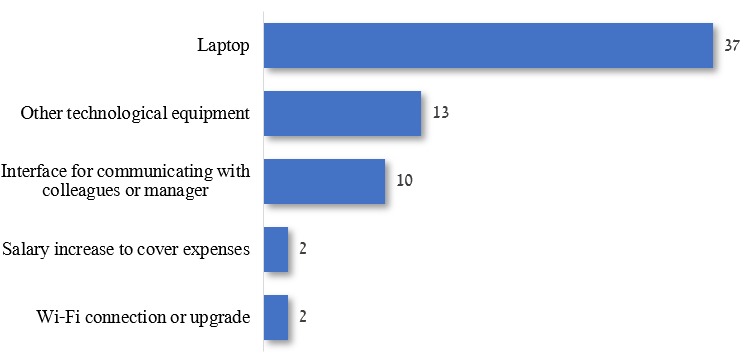

Employees were asked whether their employers had provided them with various types of support or equipment. Around half (49%) of salaried employees working from home, indicated that had received no assistance from their employers; 37% reported that they were provided with a laptop; 13% -- with other technological equipment, and 10% --with a special interface for communicating with their colleagues or with their manager. Only 2% reported having been provided with a Wi-Fi connection or upgrade, and a similar percentage reported receiving compensation for expenses incurred in working from home (see Figure 14).

Figure 14. Support for Working at Home by Type of Support: December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute, December 2020

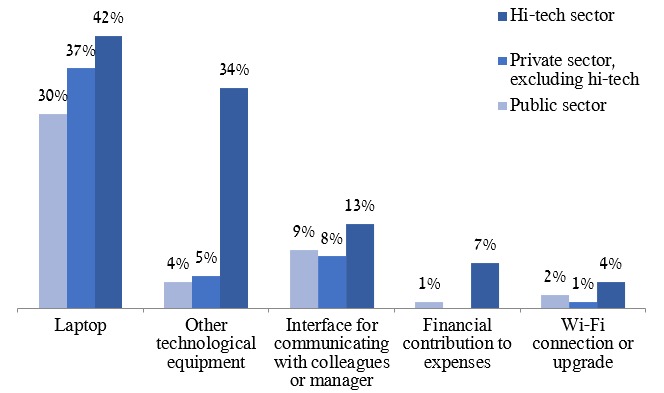

Among workers in the hi-tech sector, 69% reported having received support or equipment from their company. This compares with 46% of workers in the rest of the private sector (excluding hi-tech), and 42% of public sector workers. The main support received by workers was provision of a laptop, reported by 42% of workers in hi-tech, 37% of workers in the rest of the private sector, and 30% of public sector workers. In the hi-tech sector, 34% of workers received other technological equipment, and 13% were provided with a special interface for communicating with their colleagues or manager (see Figure 15).

Figure 15. Support for Working at Home by Type of Support and Sector: December 2020 (%)

Source: Israel Democracy Institute, December 2020

The rapid transition to working from home during the pandemic has characterized the world of work around the globe. According to data from LinkedIn for the first half of 2020 (see Figure 16), the number of remote job searches almost doubled between February and June 2020.

Figure 16. Index of Remote Job Searches on LinkedIn: February- June 2020 (February 11 = 100)

Source: WEF report, LinkedIn economic graph

A survey of employers conducted by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the first half of 2020, found that a large majority of employers (83%) intend to provide more opportunities to work remotely over the next five years. To respond to the challenges presented by remote working, and out of concern for employees' productivity and well-being, about one-third of employers expect to take steps to create a sense of community, connection, and belonging among workers through the use of digital tools.

While the pandemic has demonstrated that remote working is possible on a larger scale than in the past, employers are skeptical as to its efficiency. Most employers (78%) anticipate that remote working will have some degree of negative impact on workers' productivity, with 22% expecting a strong negative impact, and only 15% believing that it will have no impact or a positive impact on productivity.

The WEF researchers attribute employers' skepticism on the efficiency of working from home, to several factors: The sudden transition to remote working occurred during a period characterized by significant stress and health concerns; parents with young children had to cope with their children being at home for much of the time, due to the shutdown of schools ; and adjusting to physical distancing required companies to invest efforts in instilling new habits of remote working and in maintaining contact and a sense of organizational belonging among employees.

However, the WEF survey revealed that the process of companies' adjustment to hybrid and remote working was already in full swing by mid-2000, and that ensuring employees’ welfare was one of the main focuses of employers' efforts. For example, 34% reported having taken steps to create an online community for their workers.

Conclusion

The labor market of the future is already here for many white-collar workers, who have now been working remotely for a lengthy period of time. Major employers throughout the world are beginning to recognize this fact and to prepare their organizations accordingly. Working from home comes with many advantages, and this option should be extended and made available to all sectors of the population. Israeli findings indicate that workers must contend with various difficulties in working from home, and that they do not receive sufficient support in most industrial sectors.

Thus, additional steps should be taken in order to facilitate work from home. We recommend that the government take the following actions:

- Amend labor legislation so that it will support and facilitate flexible working arrangements (as is common in other countries).

- Update Israel’s internet infrastructure to ensure comprehensive broadband provision (this mainly requires regulatory action—the emphasis on price competition in recent telecommunications reforms undermined investment in infrastructure).

- Improve access to training and courses for workers and managers on time and work management when working from home, and on the use of digital tools necessary for remote working.

- Provide financial assistance to businesses (mainly small and medium-sized businesses) to support the necessary investment in adapting to remote working (such as information security, communications systems, remote access, etc.).

- Develop methods for supervising and assessing performance and productivity when working from home. As the country’s largest employer, the government should ensure the provision of productivity assessment mechanisms for public-sector workers.

- Help disadvantaged population groups enjoy the benefits of working from home, by ensuring full access to computers, internet access, and so on.

Aviram-Nitzan, Daphna, and Rachel Zaken. 2020. Survey of Working from Home During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute. [Hebrew].

Brussevich, Mariya, Era Dabla-Norris, and Salma Khalid. 2020. Who will bear the brunt of lockdown policies? Evidence from tele-workability measures across countries. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 20/88. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/06/12/Who-will-Bear-the-Brunt-of-Lockdown-Policies-Evidence-from-Tele-workability-Measures-Across-49479.

Sanchez, Daniel Garrote, Nicolas Gomez Parra, Çağlar Özden, Bob Rijkers, Mariana Viollaz, and Hernan Winkler. 2020. Who on earth can work from home? World Bank Group Policy Research Working Paper No. 9347. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34277.

World Economic Forum. 2020. The Future of Jobs Report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020.