Arabs in the Labor Market and COVID-19

The survey indicates that economic inequality between the Arab and Jewish populations in Israel has increased as a result of the COVID-19 crisis

Shutterstock

Background

This survey (the third in a series) was conducted during the second week of December 2020 (between December 6 and December 16), among a representative sample of Israelis who were working at the time of the outbreak of the economic crisis caused by the pandemic.

The survey was conducted at a time when there was a gradual easing of the restrictions imposed during the second lockdown in Israel, which ended in mid-October 2020, and prior to the imposition of increasingly stringent restrictions which culminated in the third lockdown. Thus, this survey can be considered to be representative of the situation of individuals in the labor market during the “routine” periods of the pandemic.

It should be noted that although survey participants were mainly asked to relate to their situation at the time the survey was conducted—that is, during the second week of December 2020—some of the questions (relating to salary/income) asked them to relate to November, due to the fact that salary information is available only at the end of the month.

The survey was created, designed, and analyzed by the staff of the Center for Governance and the Economy at the Israel Democracy Institute, with methodological assistance and oversight provided by the staff of IDI’s Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research. The questionnaires were administered by the iPanel online polling service.

The survey aimed to provide Israel’s economic decision makers with an up-to-date picture of the situation of the country’s self-employed and salaried employees, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis and the associated restrictions on economic activity.

Survey Sample

This survey was conducted among a representative sample of Israelis who were working when the pandemic began, comprising 767 respondents: 162 Arab Israelis, and 605, Jewish Israelis. The data on the Arab population were weighted in all analyses, to reflect the actual representation of Arabs in the workforce prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (14.5%).

Changes in Employment Status

Salaried EmployeesAll employment status questions to salaried employees in this section refer to their status in December 2020, while questions about their salary refer to November 2020. The sample of Arab self-employed workers in this survey was too small for meaningful analysis, and thus this document contains analyses only of salaried employees in the Arab population, or of the total sample, without a separate analysis of self-employed workers.

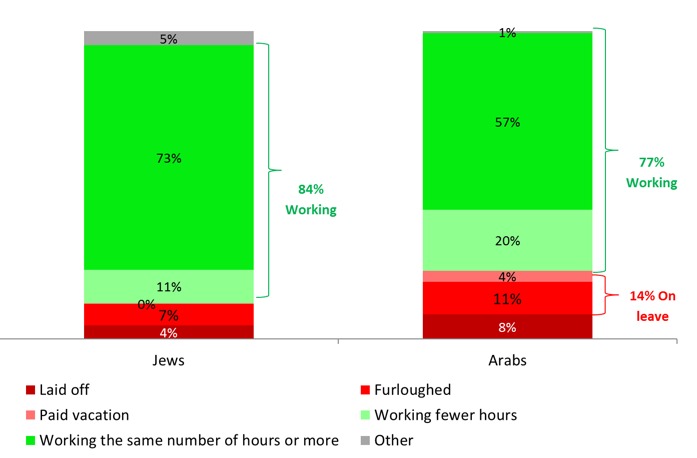

As of December 2020, approximately 22% of Arab salaried employees had been laid off or put on leave since the onset of the pandemic, compared with around 12% of their Jewish peers.

Some 8% of Arab workers had been laid off since the pandemic began, compared with just 4% of Jewish workers, and the share of Arab workers who had been furloughed is also higher, at 11%, compared with just 7% of Jewish workers.

Similarly, the percentage of Arab workers who continued working during the pandemic but were forced to take a cut in work hours, is almost double that of Jewish workers, at 20% compared with 11%, respectively.

Employment Status of Salaried Employees, December 2020, by Population Group (%)

The high percentage of Arab salaried employees who had been laid off or furloughed does not come as a surprise. The crisis has dealt a blow mainly to those economic branches and occupations in which salaries are low and in which distance working is usually not an option. Throughout the first and second lockdowns, the branches with the highest rates of unemployment were food and hospitality services, entertainment and leisure, commerce, education, and transportation. As a result, Arab Israelis were hit particularly hard, as the main blow fell on sectors which comprise a higher portion of the Arab workforce compared with the Jewish one. For example, some 16% of Arab salaried employees were employed in trade and commerce in 2019, compared with 10% of Jewish workers, and 7% of Arab workers were employed in transportation services, compared with 4% of Jewish workers.

In addition, the fact that Arabs are more likely to have occupations in which working from home is less possible (such as construction, cleaning, retail sales, driving, etc.). As a result, during lockdowns and periods in which restrictions were enforced, Arab workers were unable to continue working, even in those economic branches which were hurt less from the pandemic.

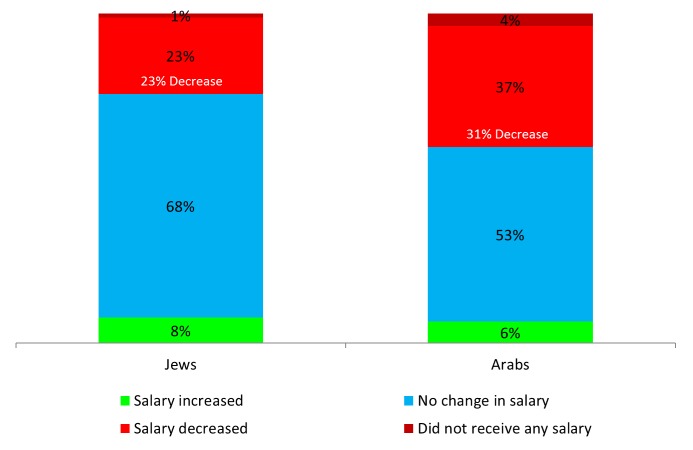

In addition, the prevalence and scale of the decrease in wages among Arab salaried employees was higher than among their Jewish peers, 41% of Arabs who were working when the pandemic broke out, reported a decrease in wagesin November 2020, as compared with just 24% of Jews. The percentage of working Arabs who reported receiving no salary at all in November (3.8%) was more than three times higher than the corresponding figure for Jews (1.2%). As noted, low-salary workers, of whom a large proportion are Arabs, were harder hit by the effects of the pandemic. The high percentage of Arabs working in manual labor occupations, combined with lower rates of digital literacy and poorer internet infrastructure in Arab locales, as compared with Jewish ones, prevented many Arab workers from maintaining their regular working hours—even those who their occupation allows them to work from home.

The scale of wage decrease was also higher among Arabs than among Jews: Salaried Arab employees reported an average decrease of 31% in their salaries in November 2020, compared with 23% among Jewish salaried employees. These figures tally with the fact that almost double the percentage of Arab workers than of Jewish workers, were forced to cut their hours.

Changes in Salary Resulting from the COVID-19 Pandemic

As compared with before the outbreak of COVID-19; among salaried employees working in November 2020, by Population Group (%) (%)

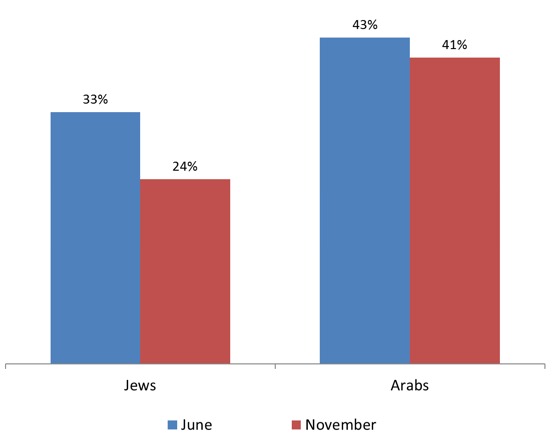

Moreover, a comparison between the June and November data on changes in salary reveals a drop in the percentage of Jewish salaried employees whose wages were hit between these two months, while almost no such change occurred among Arab workers. That is, Jewish workers were better able to adapt to the pandemic “routine” and thus mitigated the negative impact on their salaries. This finding highlights the fact that deep-seated changes are needed to enhance the ability of Arab workers to adapt to new employment formats.

Salaried Employees whose Salaries were Cut or who Received no Salary in June and November 2020, by Population Group (%)

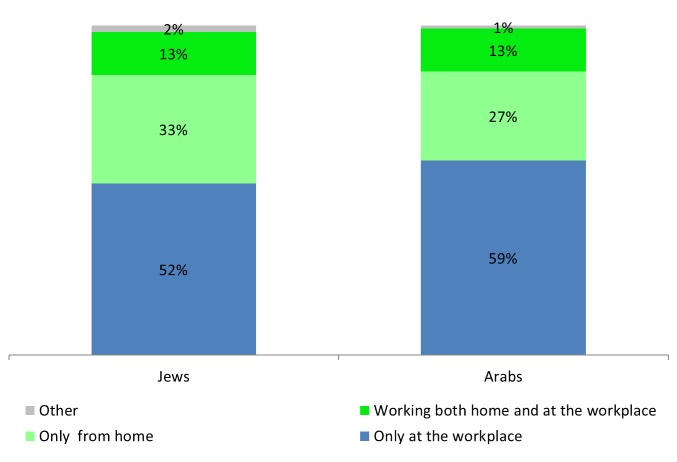

The survey also revealed that of those respondents who were working at the beginning of December, the proportion of Arabs working only or partially from home, was lower than that of Jews, at 40% versus 46%, respectively.

While an identical percentage of both groups were working only from home (13% of both Jewish and Arab workers), the percentage of those combining work at home and at the workplace was lower among Arabs (27%) than among Jews (33%).

At the same time, it is important to note that these gaps reflect the situation of those employed at the time the survey was conducted. As noted above, a higher percentage of the Arab working population left the workforce, and it is very possible that upgrading the quality of human capital and increasing the numbers of those in professional or technological occupations, alongside improving the internet infrastructure would have helped keep a greater share of Arab employees at work. Thus, we see that the gaps between Jews and Arabs are evident both in the capability to enjoy flexible working conditions, and in the actual probability to remain in employment.

Current Place of Work: Home or at Workplace

Salaried Employees Currently Working, by Population Group (%)

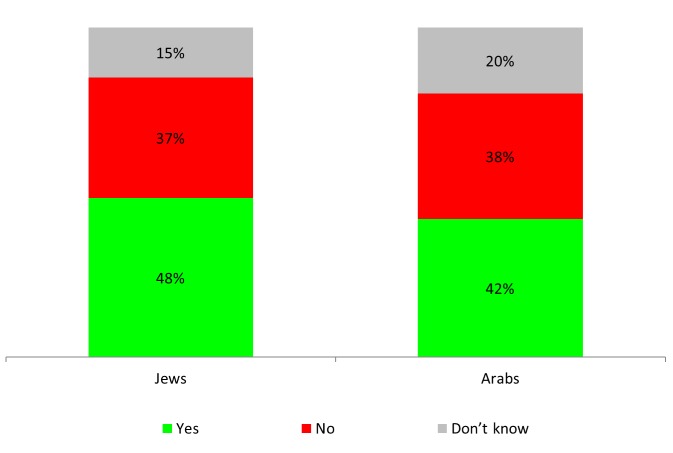

Nevertheless, the percentage of Arab respondents (both salaried employees and the self-employed) who expressed interest in participating in short-term vocational training courses (3-6 months) funded by the government, was slightly lower than among Jewish respondents (42% versus 48%, respectively). Another significant finding presented in the figure below, is that 20% of Arab workers responded “don’t know” to this question. Among Jews as well, a relatively high percentage- 15% gave the same response. This finding, along with the fact that some 37%–38% of respondents (Jews and Arabs) are not interested in participating in vocational training, can be attributed to the failings and shortcomings characterizing the vocational training system in Israel. To a large extent, this system has not been relevant to the needs and demands of the labor market and has not significantly improved the earning potential and employment prospects of its trainees. Studies have shown that this is the case even more among Arab graduates of vocational training programs, and particularly Arab women.

Would you be interested in participating in vocational training? Salaried workers, by population group (%)

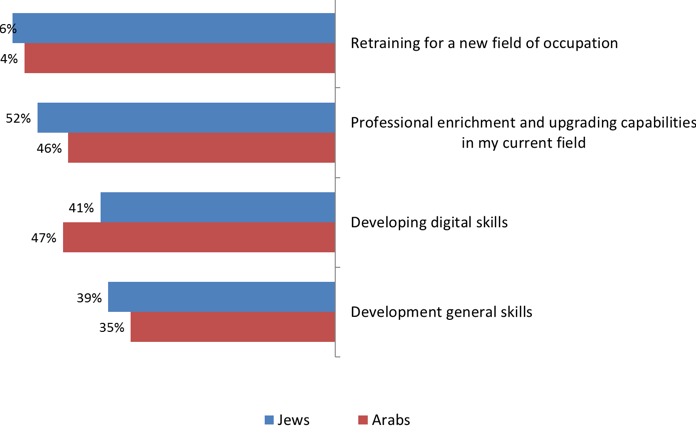

The proportion of those interested in undergoing retraining was relatively high in both population groups, at 54% of Arabs and 56% of Jews. A relatively high level of interest (46%) was also found among Arab respondents with regards to professional enrichment and upgrading their capabilities within their current occupational field (the corresponding figure among Jews was 52%).

A similar rate of interest (47%) was found with regard to courses in digital skills and/or online marketing and sales, compared with 41% among Jewish respondents.

Another reason that can explain the relatively low share of Arab workers expressing interest in vocational training is that during the pandemic, a sizeable proportion of the Arab population was in survival mode. As we shall see below, Arab society was already worse off at the beginning of the crisis, and its situation only deteriorated from then on. It is possible that many Arabs view training as a privilege that will take up precious time, and instead they prefer to direct their efforts to finding employment and increasing their family’s income.

It may be that this fact goes some way toward explaining the relatively high percentage of Arab workers interested in developing their digital skills. This type of training is seen as less demanding than vocational training, and thus as being possible to complete while also working. Of course, the relatively low level of digital skills in the Arab workforce, the effects of which have been strongly felt during the pandemic, also has an effect on the willingness of Arab workers to undergo digital skills training.

In what fields would you be interested in receiving vocational training? Respondents interested in participating in training, by population group (%)

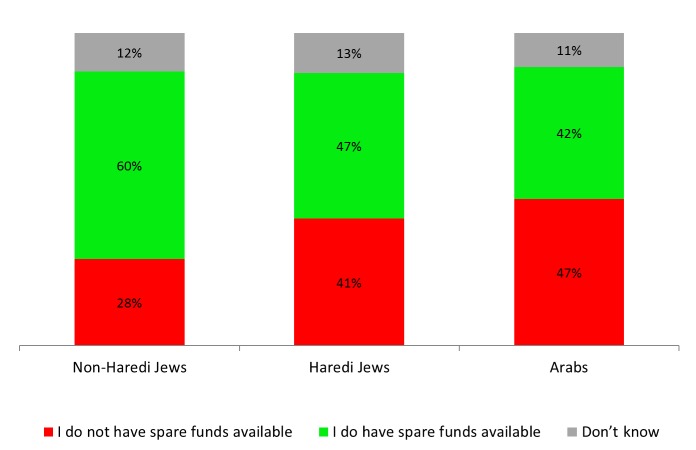

Consistently, financial liquidity is a greater problem in the Arab sector than in the Jewish sector. The share of Arab respondents who reported that they have no spare funds available (47%) was significantly higher than the corresponding share of non-Haredi Jewish respondents (27%). At the same time, it appears that the situation of Arabs in this regard has remained stable relative to June, while the situation of non-Haredi Jews has deteriorated: In July, 46% of Arabs said they had no spare funds available, compared with just 22% of non-Haredi Jews.

Do you have spare funds available? Total sample, by population group (%)

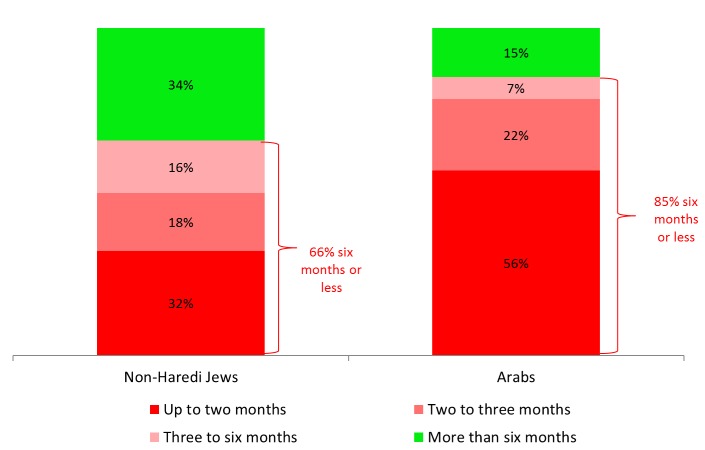

The period for which available funds are expected to last is also lower in the Arab population: 85% of Arab respondents with available funds said that these funds would be enough to support them only for up to six months (for 56%, up to two months), compared with 66% of non-Haredi Jews who said the same.The number of Haredi respondents to this question was too small to support significant analysis.

How long could you live on the funds you have available? Respondents who reported that they have spare funds available, by population group (%)

These findings are closely related to the situation of Arab society immediately prior to the pandemic. The existing low household incomes and high poverty rates made things even harder when the crisis began and limited the ability of Arab families to live in dignity. In 2019, approximately 37% of Arab families were living below the poverty line, compared with around 19% of Jewish families. Similarly, the average monthly available income for Arab households (NIS 14,600) was much lower than for Jewish households (NIS 21,500). It is no surprise, then, that such a high share of Arab respondents reported having no spare funds available, and that of those who do, more than half said that these funds would last them for less than two months.

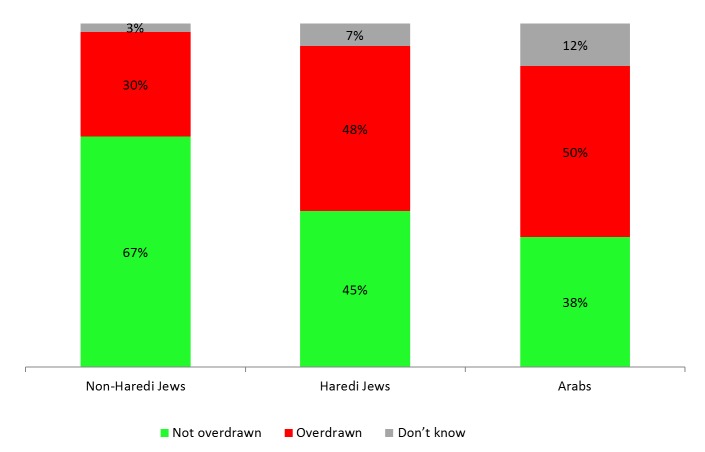

Leading on from this directly, the survey also found that half of the Arab public (50%) are currently overdrawn at the bank, compared with 30% of non-Haredi Jews. Only 38% of Arab respondents reported that their account is not overdrawn, compared with 67% of non-Haredi Jews (almost double), and 45% of Haredi Jews. It is worth noting that many in the Arab sector bank with the Postal Bank, which does not provide the option of an overdraft. Thus, it is likely that an even higher percentage of Arabs would be overdrawn if their account was not with the Postal Bank.

Is your bank account overdrawn? Total sample (%)

Overall, the survey indicates that economic inequality between the Arab and Jewish populations in Israel has increased as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Higher rates of workers made unemployed or furloughed, and greater cuts to salaries and working hours, have only exacerbated the problems that already existed in Arab society. There is real concern that many Arab families will be pushed into poverty, and that many workers who have been forced out of the labor market will not find their way back and will be sucked into chronic unemployment. These developments could have serious long-term consequences not only for Arab society in Israel, but for Israeli society as a whole. In order to prevent such outcomes, the government must invest in the proper tools to help upgrade human capital in the Arab sector, adapted for the needs of Arab society, and create greater employment possibilities for the Arab population. In particular, the government should invest in a vocational training system that will properly meet the needs of Arab society, and should also invest efforts in returning to the labor market Arab workers who have been forced out and who are at risk of becoming chronically unemployed.