Israel 2050: A Thriving Economy in a Sustainable Environment The Program’s Impact on Macroeconomic Growth in Israel

Flash 90

1. Introduction: The Israel 2050 Program Against the Backdrop of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The work on this report was carried out during the months directly preceding the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had far-reaching consequences for the local and global economy. On the one hand, the severe damage caused to the global economy will make it more difficult to invest efforts in minimizing the potential damage caused by future crises, such as the climate crisis, and may even lead to backsliding in the adoption of green practices by private and public organizations. On the other hand, the pandemic has starkly demonstrated the need for comprehensive government policies to prepare for and cope with global crises that do not stem directly from regular business cycles, as well as the need for more decisive action to prevent such crises. There has also been some initial research on the links between climate damage and the outbreak of new epidemics, and between air pollution and COVID-19 mortality rates.

Attempts to promote economic recovery from the pandemic, in Israel and around the world, are being driven by increased government spending, some of which can and should be allocated toward policy actions to reduce climate damage, as is being done in many developed countries. A detailed proposal for such double-benefit policies—which drive economic growth and employment while also reducing emissions and environmental damage—can be found in the document published by the Israel Democracy Institute together with the Green Network Israel, which offered practical recommendations to decision-makers in advance of preparing Israel's State Budget Law and the Arrangements Law for 2020–2021 (Sussman, Sharon, & Shoef-Kollwitz 2020).

Recently, the OECD also published a new document providing recommendations for reducing emissions in Israel, which focuses on the link between the wellbeing of the Israeli public, and the promotion of targets for reducing carbon emissions (OECD 2020). As we show in this report, many of the policy actions for reducing emissions that have been proposed by government ministry work teams are well aligned with the national targets for increasing growth, productivity, and employment rates. Thanks to this synergy between reducing emissions and advancing other national targets for Israel’s economy on the road to recovery from the recent crisis, implementing the Israel 2050 program for emissions reduction is not only an urgent necessity, but also highly efficient in economic terms.

2. Background

Global warming and local air pollutants are external effects of economic activity; that is, they bring with them damages that are not taken into account by economic stakeholders, and thus they have no market cost. Consequently, the damage inherent in these external effects is not fully reflected in the commonly accepted measure of economic activity—gross domestic product (GDP). According to current estimates, without a concerted international effort to reduce emissions, by 2100 the negative impact of climate change will reach a level of more than 7% of global GDP (Khan et al., 2019).

By contrast, while addressing these external effects may incur costs that can reduce the current GDP, it can also lead to growth in GDP in the future. According to estimates published by the European Commission, the net global economic impact of reducing greenhouse gas emissions will be somewhere between a decline of 1.3% and an increase of 2.19% in global GDP by 2050, in comparison with the business-as-usual scenario (European Commission, 2018). This calculation takes into account several external co-benefits, but not the health benefits resulting from reduced local polluting emissions, which the EC estimates as potentially contributing 2% to GDP (European Commission, 2017). The OECD estimate for G20 countries quantifies additional co-benefits for the emissions-reduction program examined by the organization (details are provided in Chapter 2), such as co-benefits from public investment in infrastructure, and from public and private investment in green research and development, which could lead to average GDP growth of 2.1% and 3.1% respectively, and thus ensure that the overall impact of the program on GDP will be positive (OECD, 2018).

The forecasts for a relatively limited negative impact of steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on global growth trends, along with their positive impact on growth based on several projections, reflect the fact that the cost of programs to reduce emissions are offset by their local co-benefits. They also reflect the decoupling between energy consumption and GDP, particularly in developed economies based on service industries and on research and development.

This report presents the macroeconomic implications of the program to reduce pollutant emissions in Israel, incorporating a qualitative assessment of combining it with other government economic programs, with the goal of enabling informed prioritization of programs in the context of budgetary restrictions. In addition, we used a quantitative dynamic integrated assessment model to estimate the direct costs in GDP terms of adopting programs for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Israel.

3. Qualitative Analysis of the Israeli Case

Israel’s main long-term economic goal is to close the gap in living standards between it and the wealthier OECD countries. Israel differs from most of the wealthier states in its rapid rate of democratic growth, requiring immediate investment in education, transportation, housing, and health infrastructures, simply in order to maintain the same GDP growth rate. The conclusion of our analysis is that adopting technologies based on renewable energy sources and on energy efficiency does not contradict these long-term goals—rather, it complements them. Israel is currently in the midst of a process to reduce the energy intensity of its GDP, and thus adopting energy efficiency programs will only serve to strengthen existing trends, rather than counteract them. Thus, for example, the expected rise in housing demand (almost double the number of current housing units) makes it possible to adopt green construction standards without having to impose an immediate burden on existing property owners.

The main consumer of energy in Israel, particularly polluting energy produced from fossil fuels, is transportation, followed by industry. Electrifying transportation and increasing its efficiency (by using renewable energy sources to supply the necessary electricity) is expected to have the most significant impact on reducing emissions. The current transportation crisis in Israel offers the opportunity to achieve three goals simultaneously: reduce congestion on the roads, increase work productivity (while also reducing disparities between metropolitan centers and the rural periphery), and reduce emissions. Because this requires the re-electrification of a large sector, it is also a natural way of increasing the relative share of renewables in energy consumption in Israel, without putting pressure in the early stages on existing manufacturers in industry who use polluting energy (providing that the electricity for transportation is largely produced using renewable energy). That is, concentrating efforts on these two areas—electrifying transportation and shifting to renewable energies for electricity production—can be expected to produce the most critical impact on reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Israel, even before addressing the electrification of other sectors.

In recent years, the Israeli government has been working towards achieving several additional economic goals:

• Reducing the cost of living. A major government target since the economic and social protests of 2011, has been the reduction of living costs. In this context, it should be noted that most of the steps necessary for the program to reduce emissions and transition to renewable energy, and particularly carbon taxes, involve a rise in the cost of living in the short term. However, this impact can be minimized by reducing indirect regressive taxes, particularly VAT and excise taxes. . State revenues from greenhouse gas taxes will even out these reductions.

• Increasing competition. Adopting targets for long-term reduction of emissions is not expected to have a negative impact on competitiveness. The plans for transitioning homes and small businesses to the production of electricity from solar energy may even increase competition in the energy sector. The plans to intensify urban agglomeration processes at the expense of suburban expansion are also anticipated to make the markets more efficient, by reducing costs related to consumption or transportation of goods and by creating wider markets with more buyers and sellers.

• Reducing road congestion. The proposed solutions to the problem of road congestion are very well aligned with the proposals for reducing the use of polluting energy in transportation. Examples of this congruence include plans to promote electric public transportation, cooperative transportation, two-wheeled vehicle use, and walking.

• Affordable housing. The direct short-term effect of imposing a carbon tax and introducing green construction is to raise house prices . However, maintenance costs for homes that meet environmental standards will drop, and these savings will make up for the rise in house prices, especially when interest rates remain low. Negotiating this gap between a rise in purchasing costs and a decline in maintenance costs will require special financing products. It should be noted that one of the components of the current efforts to reduce house prices is increased construction in the periphery, where land is cheaper, but this contradicts the goals of the program to reduce carbon emissions because it increases travel, and particularly the use of private vehicles.

In addition to these goals, there are new circumstances that need to be given due consideration:

• Impact on the labor market. Most salaried workers in Israel are employed in the service sector, in which there is a high level of transfer from polluting to clean energy sources, and thus the Israel 2050 program is not expected to affect employment in this area. Even if there are industries that are heavy users of polluting energy (relying directly on the use of fossil fuels), their share of the job market is not significant. . However, because the transition to a low-carbon economy may create frictional unemployment, we recommend taking steps that will affect these industries only when the economy is strong and at full employment.

• The fiscal situation. One of the barriers to the significant adoption by government ministries of emissions-reduction plans in the near future is the exceptionally large structural deficit in the budget. The need to reduce the deficit ties the government’s hands when it comes to adopting any planning and transportation projects, including projects that help reduce emissions. Dynamic general equilibrium models, such as the model we used in this study, indicate that the shift to carbon taxation instead of excise taxes and other fuel taxes can achieve the fiscal goals for tax collection as well as the goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These models also show that the benefits from subsidizing electricity produced from renewable sources are not significant (assuming carbon taxation). The theoretical literature is also clearly in favor of subsidizing capital and research and development, and against directly subsidizing the production of clean energy.

• The COVID-19 pandemic. After completing our research, and in the course of writing this report, the outbreak of the pandemic dealt a significant blow to the economy, affecting employment, small businesses, and public savings; the government deficit and public and private debt grew enormously. Implementing the plans for investment in transportation and in other green infrastructures will combine well with the government’s efforts to accelerate economic recovery from this crisis. Carbon taxes can provide a source for covering the large deficits created during this period. In addition, the lockdowns and restrictions on movement led to increased use of digital alternatives for remote working; these can continue to be used after the pandemic, reducing travel and the air pollution it causes.

4. A Quantitative Model for Examining the Cost of the Israeli Program to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

In addition to our qualitative macroeconomic analysis, we performed simulations of the adoption of policy steps for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (and in particular, taxing greenhouse gas emissions caused by energy production and consumption) and their impact on long-term economic growth in Israel, using a dynamic integrated assessment model named MESSAGEix-IL-MACRO.

Bottom-up models of the energy market incorporate extensive descriptions of the technological aspects of energy systems, including future improvements to these technologies. In these models, the solution involves a partial equilibrium in which energy demands are met, while keeping production and supply costs to a minimum. By contrast, computable general equilibrium models using a top-down method describe the economy as a whole and emphasize the possibility for replacing production sources in order to maximize company profits.

In this report, we used a model that combines both these approaches: MESSAGEix-IL-MACRO. This is a version of a model developed at the Institute of Applied Systems Analysis, adapted for implementation in Israel, which combines the macroeconomic model with the model of the energy market, in order to calculate the repeated effects of energy demand on GDP.

In the first stage of this process, the global energy model MESSAGEix-GLOBIOM was adapted to the Israeli context: a small and open economy that imports unprocessed and processed coal and oil and exports natural gas and oil products. In the second stage, the main parameters that define the Israeli energy market were input into the MESSAGEix-IL model, in cooperation with the Ministry of Energy. In the third stage, we mapped the anticipated development of the energy market in Israel through to 2050, based on government ministry projections and targets relating to emissions reduction.

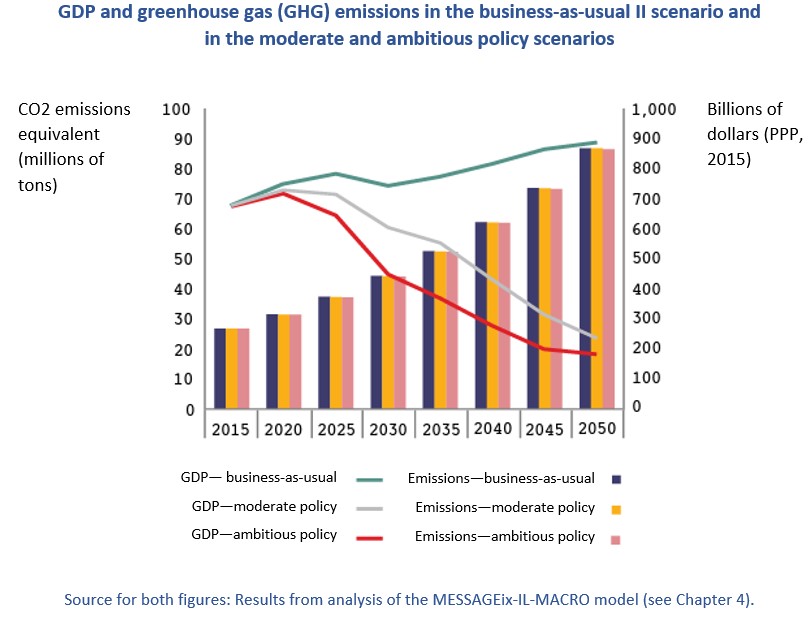

The results produced by running the MESSAGEix-IL-MACRO model were examined according to four scenarios. Two “business-as-usual” scenarios (I and II) were used as baselines with which to compare two policy scenarios: a moderate scenario and an ambitious scenario. The results of the policy scenarios show that, given either moderate or ambitious ministry targets, by 2050 it will be possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from energy production and use by around 60% and 90%, respectively, relative to the baseline year of 2005, while reducing GDP by between 0.02% and 0.62% (between NIS 210 million and NIS 4 billion, without taking into account local co-benefits, which according to international estimates outweigh the costs of such undertakings).

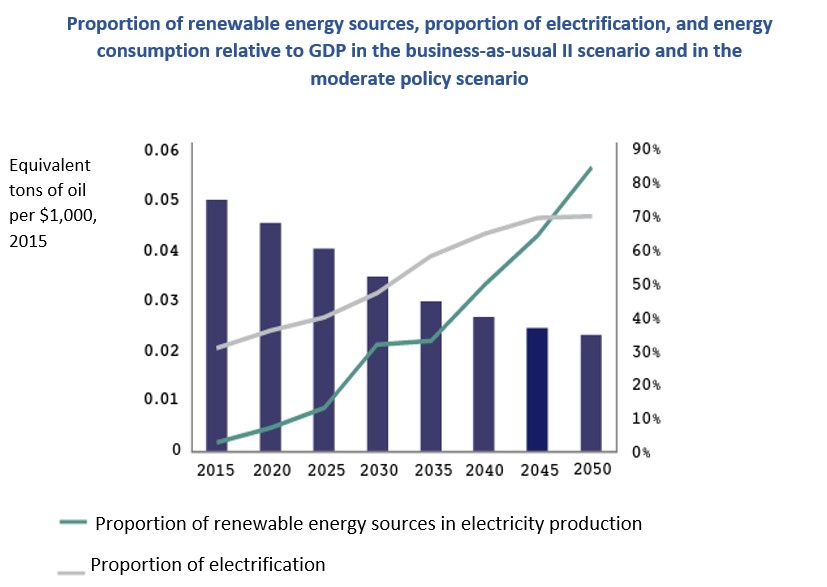

Emissions reductions are to be achieved in two main ways: (1) Improving energy efficiency, that is, reducing the energy consumption required for one product unit by around 60% relative to 2017; and (2) shifting energy production from the use of polluting fuels to renewable energy while also undertaking electrification, so that the proportion of electricity consumption based on renewable energy will rise from about 30% today to 70% in 2050, according to the policy scenarios. Increased energy efficiency and the transition to renewable energy will be partly driven by the shift to electric solutions in transport, and partly by the imposition of a carbon tax.

It is important to note that the analysis conducted does not include greenhouse gas emissions that are not caused by energy production and use, such as emissions from agriculture and waste (constituting 15% of all emissions). Similarly, as noted above, the simulation does not calculate the co-benefits of this process. These include health benefits stemming from reduced local polluting emissions (which are closely associated with carbon emissions); and external benefits such as those produced by public investment in transport and planning infrastructures and by public and private investment in green research and development—both of which carry added importance during an economic recession due to their contribution to increased productivity and to increased employment demand (as well as greater employment diversity). Our analysis also does not include the economic and social benefits accrued from reducing carbon emissions and minimizing climate damage (which are dependent on international efforts to reduce emissions, and not on direct action by Israel).

In conclusion, the direct cost in GDP terms of steps to reduce emissions and transition to green energy is negligible, relative to the subsequent accumulated economic growth by 2050. Thus, a combination of programs in the fields of transport and planning and their contribution to productivity, investment in research and development (which is expected to yield high returns), and the local health benefits deriving from this process, can together be expected to result in an increased rate of economic growth in Israel, outpacing the Bank of Israel’s long-term forecast.

5. Policy Recommendations

• Significantly reduce polluting emissions by switching to the use of electricity supplied from renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency.

• A major incentive for increased energy efficiency and for the move to renewable energy is internalization of the pollution costs incurred by using energy produced from fossil fuels. The recommended action in this area is to impose a carbon tax, which reduces the need for regulation. We recommend that this tax be combined with subsidies for transitioning to non-polluting capital, in order to minimize the impact on owners of existing polluting capital. The carbon tax income can be used to cover the large government deficits created by the pandemic.

• To achieve sustainable growth targets for Israel’s economy, we recommend adhering to the principle of synergy between adopting targets for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the need for sizable investment in infrastructures. We propose combining these investments with policies for recovering from the COVID-19 crisis.

• We view transportation as the main focus for reducing emissions in Israel. This will require significant investment from the government and immediate implementation of the necessary steps. We recommend focusing on electricity-based solutions for mass transport and an early transition to infrastructure for private electric vehicles.

• Regarding construction, we recommend planning the distribution of residential areas and employment and commercial areas in such a way that minimizes the need for travel by private vehicle, and also recommend that new construction meets environmental standards and is zero-energy—for homes, businesses, and public buildings.

• In light of the national effort to reduce housing costs, consideration should be given to creating financing products that help meet emissions-reduction targets, at least until there is a greater availability of trained workers and raw materials for green construction in Israel.

• The current situation in industry offers an opportunity to rethink policy targets that were based on the use of natural gas. At the same time, in terms of polluting emissions, using natural gas is preferable to the used of refined oil products and can help with the transition toward winding down the oil refining industry in Israel.

• We recommend providing incentives for research and development into the adoption of emissions-reducing technologies and energy efficiency technologies.