Public Opinion Survey on Socioeconomic Issues

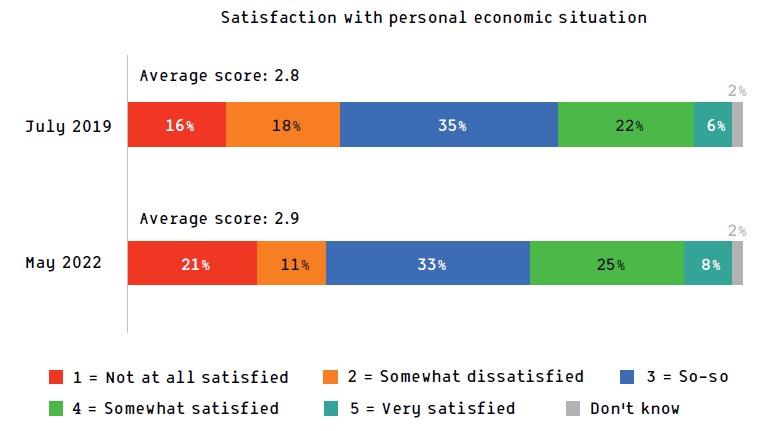

Despite the health and economic crisis that has affected Israel since March 2020, the share of those who say they are satisfied with their economic situation (“somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied”) has risen from 28% in the summer of 2019 to around 33% in May 2022.

Background

The survey was conducted ahead of the 2022 Eli Hurvitz Conference on Economy and Society (to be held on June 21–22, 2022), with the aim of providing Israel’s economic decision-makers with a clear picture of public opinion regarding the government’s socioeconomic policy, after a year in power. The survey sampled some 660 people between May 24–31, 2022, forming a representative sample of the population in Israel.

The survey was initiated and designed, and its findings analyzed, by the staff of the Center for Governance and the Economy at the Israel Democracy Institute, with methodological assistance and oversight from the staff of the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research, while field sampling was conducted by the Smith Institute.

In some questions, we compare our findings with results from a similar survey from July 2019 (before the pandemic), which was carried out in advance of the second round of elections that year, and which examined public opinion regarding the policy of the outgoing Netanyahu government. That is, the comparisons we make are between public opinions regarding the Netanyahu government’s policy, as of July 2019 (before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic and social consequences), and public opinions regarding the policy of the Bennett-Lapid government as of May 2022, following two years of an unprecedented health and economic crisis.

The Sample

The survey comprises a representative sample of the population of Israel, and includes responses from 659 adults aged 18 and above, including 503 Jews and 156 Arabs. The distribution of the respondents is representative of the population of Israel in terms of social sector, gender, age, religiosity among Jews, and geographic area of residence. Minor differences in this regard between the sample and the general population were amended via weighting.

Survey Findings

What is the public’s assessment of its personal economic situation?

Despite the health and economic crisis that has affected Israel since March 2020, the share of those who say they are satisfied with their economic situation (“somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied”) has risen from 28% in the summer of 2019 to around 33% in May 2022. The proportion of respondents who are not satisfied with their situation (“somewhat dissatisfied” or “not at all satisfied”) has stayed at around one-third, with a slight and non-significant decline from 35% to 33%.

The public’s satisfaction with its personal economic situation has remained similar to that reported in July 2019, before the pandemic

At the same time, the share of those at the extreme end of dissatisfaction (“not at all satisfied”) has risen from 16% in 2019 to 21% in 2022. Thus, though the situation has remained almost unchanged on average, it would seem that the difference between the two poles has become more acute. This finding is in line with what we know and what we reported from the various COVID surveys we conducted over the last two years—that the pandemic has exacerbated differences and inequalities in the labor market and in society as a whole.

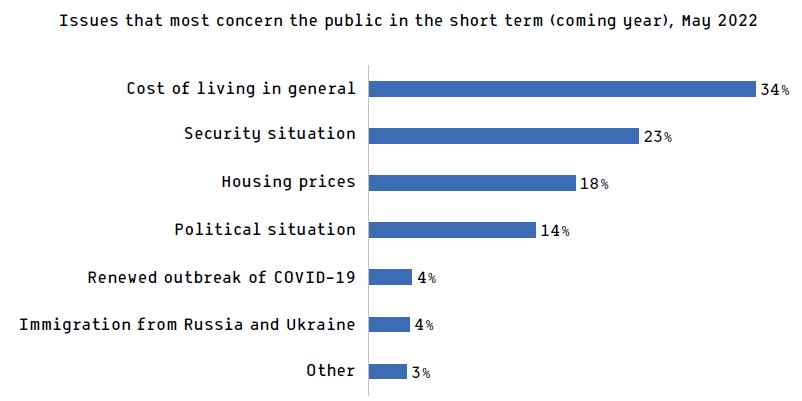

What are the social issues that most concern you in the short term (the coming year)?

Around one-third of respondents (34%) cited the cost of living as the issue that concerns them most in the short term. In second place was the security situation (23%), followed by housing prices (15%). Unsurprisingly, a high share (37%) of respondents with low incomes are concerned about the cost of living, relative to those with high incomes (31%).

Among respondents with high incomes, a relatively high proportion define the political situation as the most worrying issue (21%), compared with those in other income groups (14% on average).

A third of the public considers the cost of living to be the most concerning issue in the short term; around one-quarter, the security situation; and around one-fifth, housing prices in particular

Among respondents who voted for opposition parties at the last election, a higher proportion are concerned about the security situation (30%), relative to voters for parties in the coalition (19%).

A breakdown by age reveals that those in the main working-age bracket (25–54) are concerned about the cost of living more than are younger or older respondents (36% among those aged 25–54, versus 30% among the others), presumably due to the need to support families and children.

In addition, concern about the political situation rises with age, from 12% among those aged 18–24 to 22% among respondents aged 65 and above.

In addition, as of the end of May 2022, the Israeli public is not worried about the possible return of the COVID pandemic, relative to other issues (only 4% cited this option).

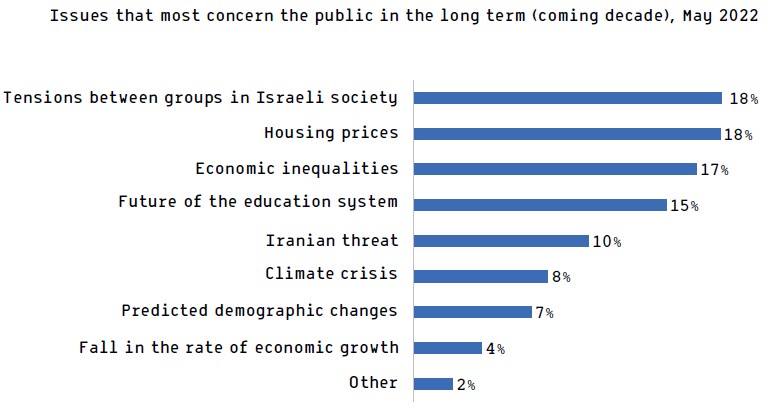

What are the main social issues that concern you most in the long term (the coming decade)?

In the long term, the public is most concerned by tensions in Israeli society (cited by 18%), housing prices (18%), economic inequalities (17%), and the future of the education system (15%).

The share of those worried about housing prices is slightly larger among opposition voters (22%) than coalition voters (17%). Likewise, a higher proportion of opposition voters than coalition voters are concerned about the Iranian threat, at 13% versus 9%, respectively. For their part, coalition voters are more worried about tensions in Israeli society—21%, compared with 15% of opposition voters.

The issues of most concern to the public in the long term are tensions between groups, housing prices, economic inequalities, and the future of the education system. The Iranian threat and the climate crisis rank below all these.

The issue of economic inequalities was cited by a higher share of respondents with the lowest incomes (22%), compared with 10% of those with the highest incomes. The climate crisis, meanwhile, is of more concern to the highest-income group (16%, compared with an average of 8% among all other groups).

Breaking down the data by age reveals that the younger age groups (18–34) are slightly more worried about housing prices in the long term than are other age groups (22%, compared with 18% on average). Similarly, the youngest respondents (18–24) are more concerned than other age groups about the climate crisis in the long term (12%, versus 8% on average).

Public ratings for government functioning

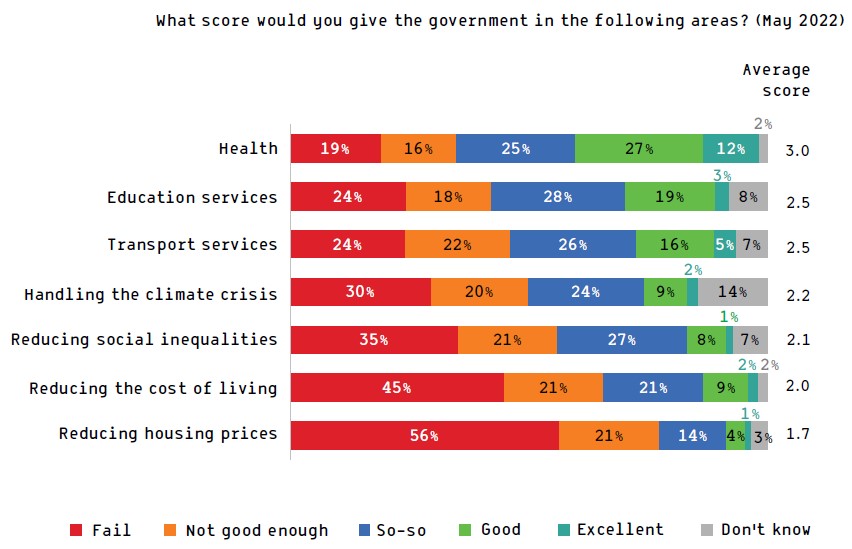

The public awards a relatively high score for health services under the current government: On a scale of 1–5, (1 = fail, 5 = excellent), the average score was 3.0. Other aspects of social service provision received lower average scores, with the lowest given to policy on lowering housing prices, which received an average grade of just 1.7.

In terms of distribution, there is a “positive net balance” in the scores awarded to health services: A relatively high proportion (38%) gave a high score (“good” or “excellent”) to the health services provided by the government, including 12% who rated them “excellent.” By comparison, 35% of respondents gave health services a low score (“fail” or “not good enough”), including 12% who graded it “fail.”

This is a significant finding, indicating relatively high satisfaction with health services at the current time—particularly against the backdrop of the pandemic, and the extensive public debates over the last two years regarding health budgets and the health services provided to citizens.

A relatively high share give high scores to the current government for health; on the other hand, a majority (56%) give a “fail” score to the government’s performance on reducing housing prices

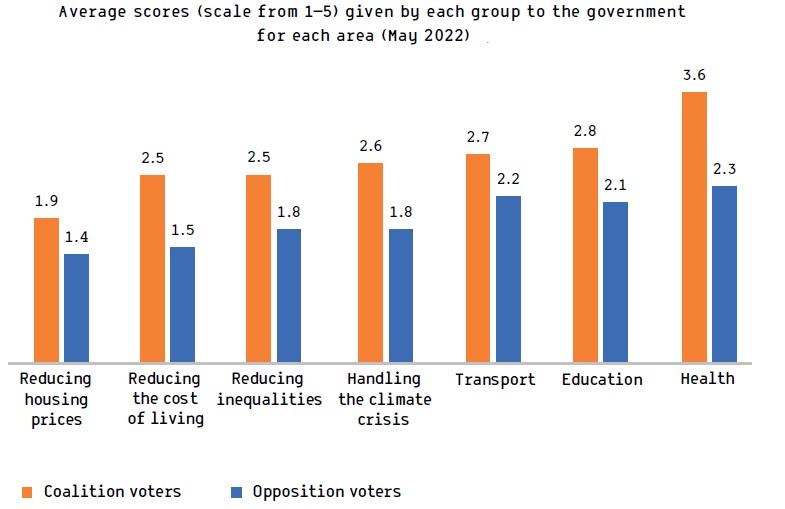

For each and every area, the average score given by coalition voters was consistently and significantly higher than the average score given by opposition voters. Thus, while coalition voters gave the government a high average grade of 3.6 on health, the corresponding grade given by opposition voters was just 2.3. Even on the issue of reducing housing prices, for which coalition voters gave a low average score of 1.9, this was still higher than the average score given by opposition voters of just 1.4 (this is a particularly low rating, and shows that a particularly large proportion of opposition voters gave the government a “fail” grading on this issue).

Opposition voters give a lower grade to the current government than do coalition voters, for each and every area

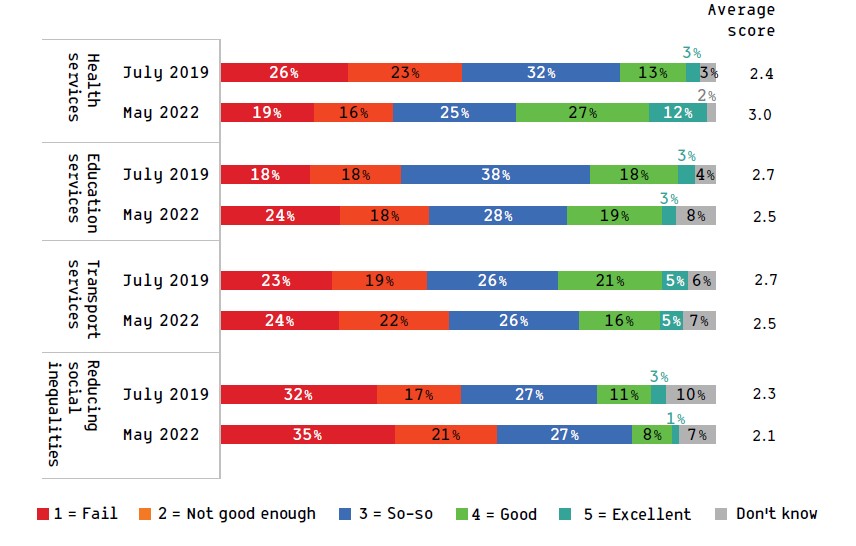

The government’s average score on social issues in May 2022 remains identical to the one it received in 2019, at 2.53. This stems from the fact that in three areas (education, transport, and reducing inequalities), the current government received a similar but slightly lower score relative to its predecessor, while for health it received a much higher score than the previous government.

The high score that the current government received from the public for health services—3.0 on average—is significantly higher than that awarded the previous government in the summer of 2019 (2.4). This finding is particularly noteworthy, as already stated, given that it comes despite the coronavirus pandemic and the extensive recent public debates on health services.

Other aspects of government functioning receive similar but slightly lower scores compared to those given to the previous government in July 2019. Thus, for both education and transport, the current government received an average of 2.5, compared with 2.7 in July 2019; and for reducing social inequalities, the current government received an average grade of 2.1, compared with 2.3 in 2019.

Health services received a higher score in 2022; other grades are similar to those given in 2019, though slightly lower

The public’s willingness for taxes to be increased

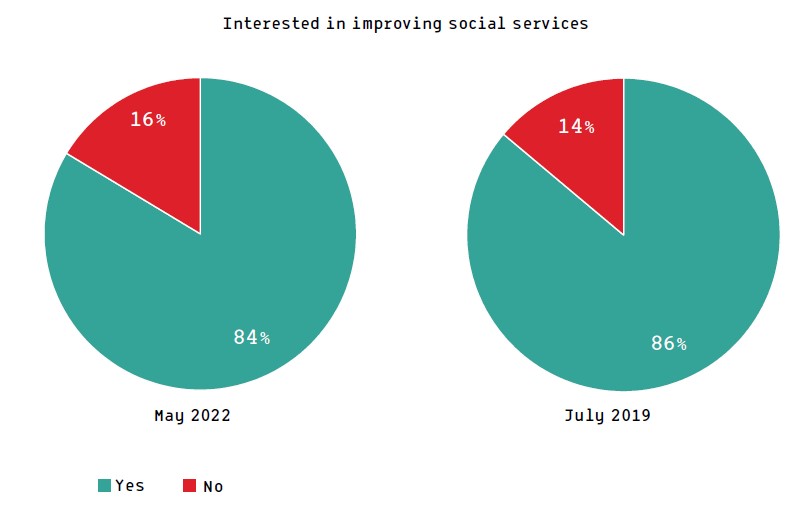

The Israeli public is clearly and consistently interested in the improvement of social services: As of May 2022, 84% say they are interested in services being improved, a slight and non-significant drop from 86% in July 2019.

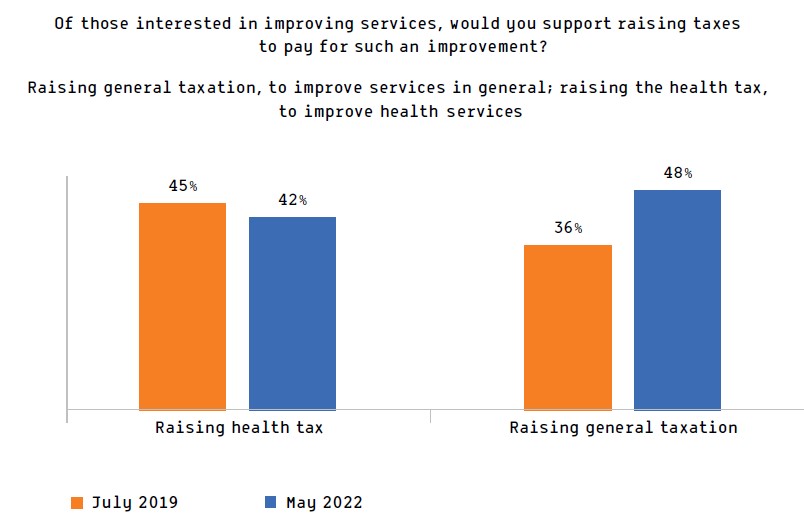

While the desire for services to be improved has remained at a similar level, there has been a considerable increase in willingness to pay more tax in order to fund this: In May 2022, around half (48%) of those who say that they are interested in improving public services are also willing to pay more taxes (in general), compared with 36% in July 2019, before the pandemic.

On a specific question about raising the health tax in order to improve health services, the current survey found a slight and non-significant decline in public willingness to increase the tax, from 45% in 2019 to 42% in 2022.

An overwhelming majority of the public are interested in improving social services (education, health, welfare, and transport), a similar situation to that before the pandemic

Significant increase in public willingness to pay more taxes (in general) to fund services, and a slight decrease in willingness to pay more health tax

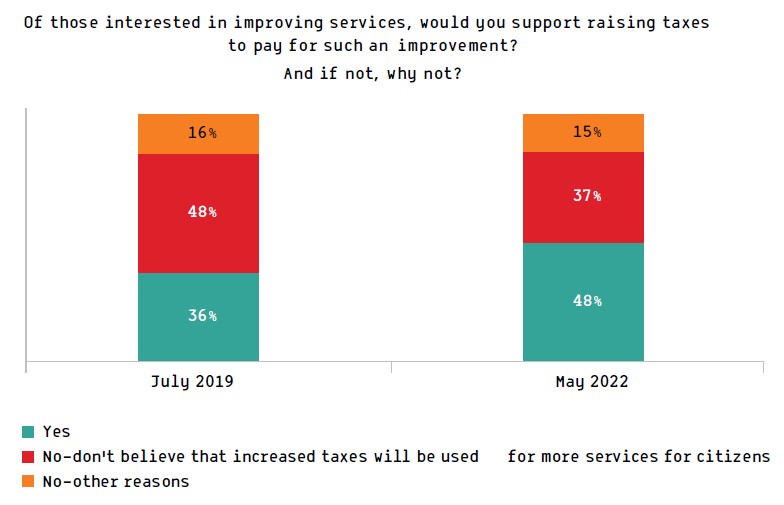

The large increase in willingness to pay higher general taxes shows that, despite the health and economic crises caused by the pandemic, trust has grown stronger: The public has greater trust in the ability of the current government, relative to the transition government of 2019, to translate higher taxation into better services. This can be seen in the figure below: When asked about the reasons why they would not be willing to raise taxes, almost half (48%) said in 2019 that they did not believe that higher taxes would be used to provide more services, compared with 37% in May 2022.

Rise in trust: In 2022, a lower share do not believe that increased taxes will be used to provide more services

Of those interested in improving services, would you support raising taxes to pay for such an improvement?

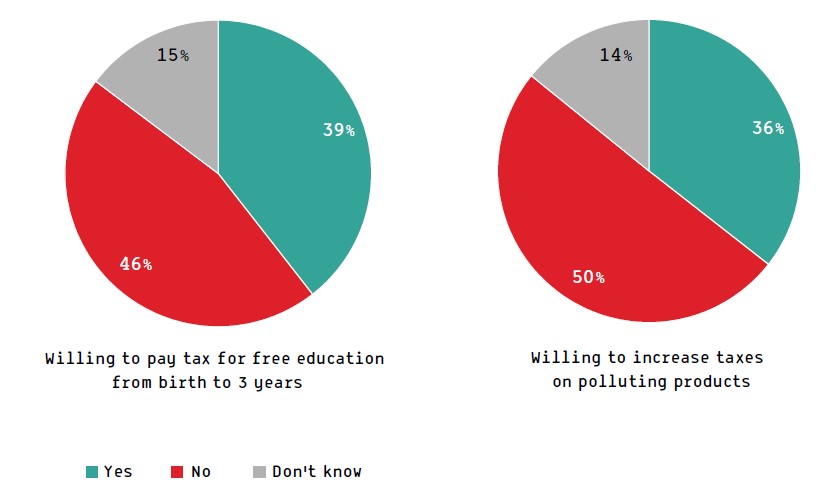

While presumably there is a broad consensus among the public regarding both the need to reduce pollution in light of the climate crisis and the need for free education from birth, people are not necessarily willing to pay for these steps. Around 36% would consent to greater taxation on polluting products, which would result in price rises (compared with 50% who are opposed and 14% who don’t know); and 39% are prepared to pay more tax in order to fund free education from age 0–3 (while 46% are opposed and 15% don’t know).

Only around 30–40% of the public are willing to pay more tax in order to fund free education from birth, or to raise prices on polluting products