The Curtailing of Judicial Review and Economic Indices

Will the overhaul of Israel’s judiciary impact Israel’s economic stability?

Photo by Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock

In light of the public debate on the series of reforms that would curtail the independence of the judicial system and of judicial review of actions by the Knesset and the Government—including by passage of an override clause by a majority of 61 Knesset members, which would limit judicial review of legislation; elimination of the ground of reasonability, which would lesson judicial review of Government actions; increased political influence on the selection of judges; a change in the seniority system for the appointment of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; and the conversion of ministry legal counsels into political appointees—we wish to investigate whether and how constitutional changes of this sort might also have an economic impact on Israel and its citizens.

The various features of liberal democracy, including free and equal elections, limits on the executive (by the courts and by the legislature), equality before the law, and defense of individual and human rights, are significant, first and foremost, to protect citizens and their freedoms and to prevent the regime from abusing its power. Nevertheless, we would expect a democratic government to wield its power to better citizen’s lives, both politically and materially, and not only to avoid harming them. Such an improvement in living standards can be expected to be manifested in terms of economic prosperity as well.

The academic literature corroborates this expectation. Economic research has found that democratization has a positive effect on economic growth, one that is long-term and cumulative (Acemoglu et al. 2019; Mukand and Rodnik, 2020). With regard to the components of liberal democracy, studies have found that the institutions that are inherent to democracy also have a positive effect on growth, and that countries that maintained their democratic institutions grew more than those in which these institutions were weakened. Institutions that were identified as especially important include the defense of free and equal elections, parliamentary limits on the executive, and freedom of expression. In light of the research, an erosion of these institutions is liable to harm economic growth (Boese and Eberhardt, 2022). In the face of the initiative to weaken the capacity of the judicial branch to review and oversee the executive and legislative branches, and the possible curtailment of its independence, we focus in this document on the research literature that examines the importance of an independent judiciary for a country’s economy.

What are the mechanisms by which an independent judiciary guarantees economic growth? First of all, it promotes growth on the basis of its ability to protect contractual and property rights and to rule fairly in disputes among citizens, companies, and government agencies. Research which attempted to assess the link between institutional arrangements and growth, has found that an independent judiciary is positively correlated with growth (Feld and Voigt, 2003). According to this research, the judiciary is a quasi-agent that enables the economy to function without fear of the sovereign’s arbitrary power. Even if the state is strong enough to change the rules of the game in a sudden and opportunistic manner, an independent judiciary can keep those rules consistent and stable even when there are frequent changes in policy (ibid.).

A subsequent study examined the relationship between de-jure (as in the legal framework) and de-facto judicial independence. It found that only the latter is robustly correlated with economic growth. This research examined the link between judicial independence and other characteristics of the regime and found that in countries in which there are many checks and balances between the branches of government, in practice, the independence of the judiciary is more strongly linked to growth. In addition, it was found that in parliamentary regimes (as in Israel), an independent judiciary has a positive effect on the GDP at approximately 1% growth a year, although the number of relevant countries was too small to arrive at a statistically significant effect at this resolution (Voigt, Gutmann and Feld, 2015).

At the same time, democratic institutions are often harmed by an economic crisis (Djuve et al, 2019). By the same token, a regime with lesser judicial review may be able to introduce reforms that would have been more difficult to enact with more extensive judicial review and a less stable government (Forteza and Pereyra, 2018; Jones and Olken, 2005). This may result in higher growth, at least in the short-term, as a function of the nature of the reform. One study does in fact assert that the weakening of the judiciary in Hungary helped that country introduce essential reform of its financial system, while making its markets more competitive, thanks to government subsidies that propelled growth (Kolozsi et al, 2018). On the other hand, the proximity in time with the economic crisis makes it difficult to break down the relevant growth factors. Another study indicates that the Hungarian policy did not actually promote the recovery, which would have taken place in any case, as a result of factors beyond government control (Csaba, 2022).We should also note that the bulk of the reforms commended by Koloszi et al. took place after the EU forced Hungary to modify its policies to comply with the recommended practices of the European financial institutions and undertake to refrain from any sudden policy changes of the sort that marked 2010–2013. See the discussion on Hungary below.

Another research approach focused specifically on the link between limits on the executive and investment. Here the emphasis was on the impact of restrictions on the executive (judicial and parliamentary) on investors’ expectations of a stable return. The study indeed found that in countries with weaker restrictions on the executive, a change in the government curtailed growth, whereas in countries with more stringent limits, the advent of a new government was accompanied by continued stable growth. This study found that investors’ expectations correspond to this pattern, and that investment indeed drops when there is less oversight of the executive branch (Cox and Weingast, 2018). Studies that focused specifically on how limits on the executive affect foreign investment found a positive causal link that was strong and statistically significant (Besley and Mueller, 2018; Mohammadf, 2021).

Direct foreign investments play a significant role in economic development. Hence, their positive impact that accompanies effective judicial and parliamentary oversight of the executive, translates into a positive effect on growth as well, in addition to the direct positive effect on growth of change in government.

To sum up, going beyond the general benefits of the democratic system, the economic literature shows that effective restraints on the executive and an independent judiciary have a positive effect on growth, since such restraints contribute to policy stability even when a change of government occurs, protection of the rule of law, certainty about the rules of the game, and encouragement of foreign investment. Because these studies had to draw on the largest possible sample of countries in time and space, they compared countries with different types of regimes and political cultures, ranging from dictatorships, through hybrid regimes and liberal democracies, whose relevance to the Israeli case is limited.

We will now describe few cases of democratic countries that have seen a decline in the power of the judiciary in recent years and examine the link between the weakening of the judiciary the economy, and how the credit rating agencies and foreign investors reacted to the changes in various countries.

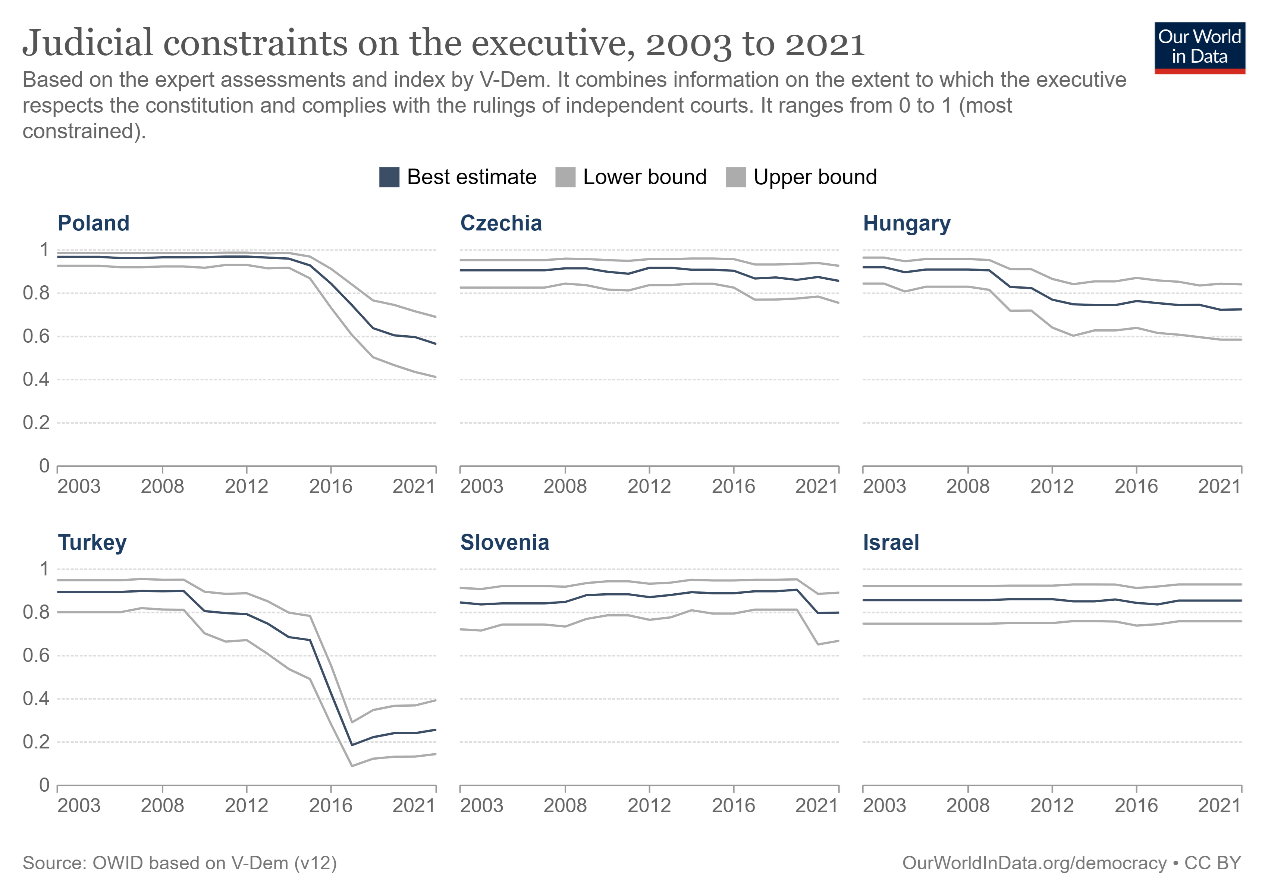

Since 2010, four OECD member countries have experienced a significant democratic backsliding, manifested in the weakening of checks and balances among the branches of government, and especially in the reduced ability of the judicial branch to review actions of the legislature and executive: Hungary (where the process began in 2010), Turkey (2016), Poland (2016), and Slovenia (2020). As can be seen in Figure 1, which is based on the V-Dem index based on the weighting of various parameters of democracy in countries around the world, in recent decades all four of them curtailed the ability of their courts to review the actions of the executive. Here we will focus on the first of three of these countries.In Slovenia, too, there has been a democratic backsliding, manifested in part by the refusal of the Slovenian Democratic Party to comply with court rulings, including its unlawful restrictions on the press; this alongside a campaign of slandering the courts and accusing them of responsibility for the scale of pandemic mortality in the country (Freedom House, Slovenia Report, 2022). Even though the processes are similar, though, the interval since the curtailment of the judiciary’s powers in Slovenian is too short for a study of its economic impact.

Figure 1: Index of Judicial Review of the Government, in Selected Countries, 2003–2021

Source: Our World in Data, based on the V-Dem index. This index weights various indicators of the judiciary’s independence and its ability to constrain the executive, including the extent to which the executive respects the Constitution and complies with court rulings.

Hungary

Viktor Orbán, who has served as prime minister consecutively since 2010, launched a series of legislative and constitutional changes that altered the electoral system, curtailed the independence of the courts, and limited the court’s ability to review actions by the government and parliament (Ron, Kremnitzer, and Shany 2020).

The assault on the judiciary was accompanied by attempts to undermine the independence of the Central Bank, but the EU Council stepped in and was able to thwart them.European Central Bank, The ECB expresses concern about the independence of the central bank of Hungary, 22 December 2011: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2011/html/pr111222.en.html

In 2015, the Hungarian government moved to limit the number of foreign banks in the country and introduce a series of retroactive laws and taxes that harmed the banking system in the country. These steps dealt a blow to the Hungarian economy (as will be seen below). In 2015, the Hungarian government signed an agreement with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in which -in a series of measures-it acquiesced to reduce the damage to the banking system.EBRD, Hungary and the EBRD join forces to strengthen financial sector and bolster economic growth, 2015: https://www.ebrd.com/news/2015/hungary-ebrd-and-erste-group-join-forces-to-strengthen-financial-sector-and-bolster-economic-growth.html

Poland

The "Law and Justice" party (PiS) came to power in 2016. The new government refused to permit the justices of the constitutional court appointed by the previous government to take office, appointed others in their place, lowered the retirement age for judges so as to bring about the retirement of judges serving on the bench, and passed legislation to limit the powers of the Supreme Court (Ron, Kremnitzer, and Shany 2020). Although this led to friction in Poland’s relations with the EU, which we will address in detail below, the government did not take any significant measures affecting the country’s economic institutions.

Turkey

As a consequence of failed coup in 2016, President Erdoğan purged government institutions. this included the arrest of hundreds of judges (Ron, Kremnitzer, and Shany 2020).The steps to weaken the judicial system began even before 2016, but to stay in line with the V-Dem indices we accept that the watershed came after the events of 2016. See Figure 1. He also diminished the independence of the Central Bank, in part by firing two governors who refused to adopt the monetary policy he wished to promote, by means of an emergency decree and not in accordance with the legal grounds for dismissal. In the end, he appointed a Central Bank Governor who accepted his unorthodox view that high interest rates cause inflation and who lowered the interest rate despite the surging inflation (which in recent months has reached 85%).Financial Times, Turkey scraps minimum term for central bank chief, July 9 2018: https://www.ft.com/content/4448afee-838a-11e8-a29d-73e3d454535d.

As noted, we expect that by safeguarding the rules of the game and promoting certainty as to government policy, an independent judiciary and the ability to review government actions are also reflected in a country’s economic performance. So in order to investigate the link between judicial independence and economic performance in the short term, we will focus on the countries’ credit ratings and the volume of foreign investment, since these respond very quickly in response to changes that affect expectations of economic developments, and especially a country’s risk profile. By way of comparison, we have added to the relevant graphs, data for the Czech Republic a (another Eastern European country that moved from a Communist regime to a free-market democracy at the same time as Poland and Hungary, and showed similar economic performance), as well as for Israel and the average of the OECD member states.

As stated, to the extent that an attenuation of the judicial system may be expected to have negative impact on a country’s economy, one anticipates that this will be reflected in investors' expectations, manifested in part in the rating of the country’s bonds and the extent of foreign investment. Figure 2 shows the credit ratings of the selected countries in the years before and after the weakening of their judiciaries.

Figure 2: The Mode of the Annual Credit Rating by the Four Main Rating Agencies, 2005–2021

Source: Trading Economics. The rating displayed is the mode rating for each year by the four credit rating agencies: S&P, Fitch, Moody’s, and Scope. Their rating scales are slightly different, and we have recoded them into a single scale. The point of democratic backsliding is marked in red; the line between investment-grade and junk bonds is in black.The data are based on the authors’ adaptation of https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/credit_rating/, scraped in December 2022.

In Hungary, after many years during which government bonds were considered a good investment, the rating began to fall at the time of the economic crisis in 2009. Nevertheless, some of the rating agencies issued statements about the policies of the Orbán government and noted that its unorthodox economic policies, which included a reduction in the independence of the Central Bank and the banking system, and that undermined investors’ confidence and stood in the way of agreements with the European Union and IMF was an element in its decision.Bloomberg, “Hungary’s Long-Term Credit Rating Cut to Junk by Fitch”, 2012: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-01-06/hungary-s-long-term-ratings-are-cut-to-junk-by-fitch-amid-financial-crisis?leadSource=uverify%20wall Hungarian bonds regained their investment-grade rating after a change in economic policy that included a reduction in debt, European assistance, and the agreements that the Hungarian government reached with the EBRD.Bloomberg, “Hungary Sees More Upgrades After Fitch Returns Investment Rating”, 2016 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-20/hungary-sheds-junk-status-at-fitch-as-debt-reduction-pays-off?leadSource=uverify%20wall

Despite the agreements with the European institutions, the rating agencies still view Hungary’s political climate and assault on democratic institutions as undermining the country’s stability; this reduces its credit rating, and the threat of a further cut still remains.Reuters, In a first, European Union moves to cut Hungary funding over damaging democracy, September 18, 2022: https://www.reuters.com/world/first-eu-seen-moving-cut-money-hungary-over-damaging-democracy-2022-09-18/ For example, the European rating firm Scope wrote in December 2021: “In Hungary, the government’s strong presence in the corporate and financial sectors, its increasing intervention in the judiciary and the media … have led to ongoing legal disputes with the European Commission. In Scope’s view, the polarized political environment in Hungary and political headwinds with the EU limit long-term policy predictability, which could weigh on the inflow of future foreign investment.”Scope, Scope affirms Hungary’s credit rating at BBB+ with a Stable Outlook, December 2021: https://www.scoperatings.com/ratings-and-research/rating/EN/169565

In Poland, the country’s credit rating was not affected by the retreat from democracy (except for a temporary reduction by S&P, which has since returned to its former level). Poland’s economy has been functioning relatively well; growth is stable; unemployment is low, and the diverse composition of its exports helps maintain a balanced economy. All these provide favorable conditions for foreign investment. On the other hand, the regulatory bureaucracy is relatively complex, legal security had diminished, and the government is attempting to reduce foreign entities’ control of the economy. These factors produce investor uncertainty (BTI Poland Country Report, 2022). Nevertheless, none of this has significantly reduced foreign investment.

It does seem likely, however, that the reason why Poland’s credit rating has not risen in the past six years, despite the relatively strong growth—unlike the higher credit ratings received then by Israel, Slovenia (before the assault on its judiciary), and the Czech Republic, which had similar economic performance—is linked to the weakening of its courts during that period. A hint of this can be found in statements by the rating agencies at the start of the process:

“Standard and Poor’s (S&P) unexpectedly cut Poland’s credit rating a notch on Friday, saying the new government has weakened the independence of key institutions, and the rating could fall further. … The downgrade reflects our view that Poland’s system of institutional checks and balances has been eroded significantly.”Reuters, S&P shocks Poland with credit rating downgrade, January 15, 2016: https://www.reuters.com/article/poland-ratings-sp-idUSL3N14Z532

Here we should remember that the European Union can impose economic sanctions and prevent member states from receiving budgets from EU agencies. In 2016, the EU launched negotiations with Poland on the reforms that the country was promoting; the threat of sanctions led the government to drop some of its planned moves against democracy. The threat of EU sanctions is one consideration in the decisions of the credit rating agencies: it restrains moves to harm democracy, thereby moderating the damage to the credit rating; but on the other hand the credit rating is liable to be lowered if sanctions are actually imposed. The continued the tension between Poland and the EU increases the probability that the latter will impose sanctions on Poland; this has produced negative forecasts concerning the credit rating by some of the agencies.Scope, Scope revises the Outlook of Poland to Negative, affirms A+ credit ratings, January 2022: https://www.scoperatings.com/ratings-and-research/rating/EN/169778; Fitch Rating, Poland-EU Constitutional Court Ruling Is Negative for Growth, Governance, October 2021: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/poland-eu-constitutional-court-ruling-is-negative-for-growth-governance-15-10-2021

In Turkey, the credit rating plunged after a few years during which its bonds were ranked as safe investments; some of the rating agencies noted the political climate and the attack on the system of checks and balances as a reason for reducing the country’s credit-worthiness.Bloomberg, “S&P Cuts Turkey Credit Rating, Citing Political Uncertainty “,2016 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-07-20/s-p-cuts-turkey-credit-rating-citing-more-political-uncertainty?leadSource=uverify%20wall As we noted above, in the Turkish case, the fears of investors and the rating firms proved to be justified, given the raging inflation there that stemmed directly from the president’s intervention in the Central Bank’s monetary policy. This intervention, as we saw, involved the use of emergency decrees and the dismissal of Central Bank governors who refused to cooperate with the president's unorthodox economic views (Demiralp & Demiralp, 2018). We can assume that stronger judicial review could have moderated these steps.

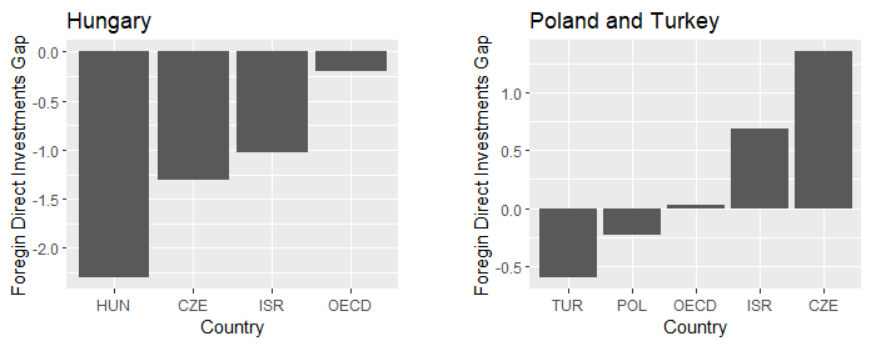

The drop in these countries’ credit rating was accompanied by a decline in foreign investment, especially in Hungary, where foreign investment declined significantly during the years when its credit rating was low (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows that in Hungary, Turkey, and Poland, the gap between the average foreign investment in the years after the democratic retreat and that before it, is smaller than that in Israel, the Czech Republic, and the OECD. This may be evidence of the blow to foreign investment resulting from the assault on democracy in these countries.

In the case of Hungary, the difference is negative. that is, there was a decline in foreign investment both before and after the democratic backsliding (which is also the period after the global financial crisis); there was also a decline between those two periods for Israel, Czechia, and the OECD average. As can be seen, however, for Hungary, the difference is larger (in absolute terms), meaning that foreign investment in Hungary was negatively affected as compared to that in other countries in those years (Figure 4).

In Turkey and Poland there was a decline in foreign investment after the first attacks on their judiciary, whereas in Israel, the Czech Republic, and the OECD, the same years saw an increase in foreign investment (Figure 4). That is, in light of the statements by the rating agencies and the change in the rating trend for countries in which the judiciary’s independence was curtailed, it seems reasonable to assume that the latter was the cause of the decline in foreign investment.

Figure 3: The inflow of Foreign Direct Investments as a Percentage of GDP, 2005–2021; the Start of the Democratic Backsliding is Marked in Red.

Source: OECD

Figure 4: The Difference in Average Foreign Investment as a Percentage of GDP, Before and After the Democratic Backsliding in Hungary, Poland, and Turkey

Source: OECD. For the graph that relates to Turkey and Poland, the average before the assault on democracy is computed for 2005–2015; for after it, for2016–2019 (in order to avoid the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic). For the graph with regard to Hungary, the average before the democratic decline refers to 2005–2009 and for after it to 2010–2019.

One of the most worrisome characteristics of democratic backsliding is the concentration of power in the hands of the executive, with a concomitant reduction in the power and independence of the other branches of government, and especially the judiciary. It is judicial review that provides certainty about the rules of the game and that limits the government’s ability to intervene in institutions entrusted with applying mechanisms for oversight and regulation, including the Central Bank. We have seen here that these processes are liable to have a negative effect on significant economic indices, such as a country’s credit rating and the volume of foreign investment.

Here it should be emphasized that with regard to Hungary and Poland, the EU functions as a higher authority that ensures some safeguarding of democracy and independence of the various institutions in the country. This is manifested in the EU's direct intervention in government moves in Hungary and the abandonment of some antidemocratic steps in Poland. Nevertheless, in Hungary, too, the credit rating was reduced after steps began to be taken to curtail the power of the judiciary; in Poland, it was not raised, unlike the countries used for comparison, and despite the country’s relatively strong economic performance. In Turkey, there is no supreme institution that oversees activity in the country, and it can be seen that the steps by the government and reduction of the Central Bank’s independence led to a drop in the country’s credit rating as well as in foreign investment.

These findings are consistent with the relevant economic literature, which emphasizes the importance of judicial constraints on the executive in order to preserve economic stability even after a change of government, as well as the judicial system’s stabilizing effect on investors’ expectations and uniform rules of the game that encourage growth.

We anticipate that the new laws advanced by the new Israeli government will weaken the judicial system and its ability to exercise oversight and review of the actions of the government and the Knesset. This is liable to lower the country’s credit rating and investor confidence and to reduce foreign investment in the country. Additionally, in Israel there is no international body such as the EU that can impose sanctions and curtail the steps to undermine democracy and the judiciary and to moderate investors’ fears of government policy. Even if the probability that the government will promote an extremely harmful economic policy is low, there are strong grounds for thinking that a significant weakening of the checks and balances in the country will increase the risks that such a policy might come about, with a consequent increase in the risk faced by citizens and investors.

This is not mere idle talk; it was stated explicitly by a representative of S&P in an interview with the Calcalist website: “A consistent tendency to weaken key and essential institutions or the system of checks and balances is liable to increase the risk of the reduction of Israel’s credit rating." And later:

When we refer to institutions and institutional order we are referring to the entire structure: the mode of government action, the independence of the Bank of Israel, the judicial system, the extent of the public discourse, and of course- the system of checks and balances that does not allow the Government to decide on its own without the participation of the other institutions and which guarantees that the policy will be appropriate, at a high level, and suitable for the goal.”https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/sk8m7xp5o

As we have seen in the comparative graphs, Israel is still very far from countries like Hungary and Poland, and its economic situation is immeasurably better than that of Turkey. Still, it is important to understand that there is a link between steps that on the surface do not seem to be related, such as the capacity for judicial review of government actions and investors’ confidence in a stable economy.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of political economy, 127(1), 47-100.

Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2022 Country Report — Hungary. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022.

Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2022 Country Report — Poland. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022.

Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2022 Country Report — Turkey. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022.

Besley, Timothy, and Hannes Mueller. “Institutions, volatility, and investment.” Journal of the European Economic Association 16.3 (2018): 604-649.

Boese, Vanessa Alexandra, and Markus Eberhardt. “Which Institutions Rule? Unbundling the Democracy-Growth Nexus.” Unbundling the Democracy-Growth Nexus (February 11, 2022). V-Dem Working Paper 131 (2022).

Cox, Gary W., and Barry R. Weingast. “Executive constraint, political stability, and economic growth.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 3 (2018): 279-303.

Csaba, László. “Unorthodoxy in Hungary: an illiberal success story?” Post-Communist Economies 34.1 (2022): 1-14.

Demiralp, Seda, and Selva Demiralp. “Erosion of Central Bank independence in Turkey.” Turkish Studies 20.1 (2019): 49-68.

Djuve, Vilde Lunnan, and Carl Henrik Knutsen. “Economic Crisis and Regime Transitions from Within.” V-Dem Working Paper 92 (2019).

Feld, Lars P., and Stefan Voigt. “Economic growth and judicial independence: cross-country evidence using a new set of indicators.” European Journal of Political Economy 19, no. 3 (2003): 497-527.

Forteza, Alvaro, and Juan S. Pereyra. “When do Voters Weaken Checks and Balances to Facilitate Economic Reform?” Economica 86, no. 344 (2019): 775-800.

Freedom House, Slovenia report, 2022: https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovenia/freedom-world/2022

Jones, Benjamin F., and Benjamin A. Olken. “Do leaders matter? National leadership and growth since World War II.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120.3 (2005): 835-864.

Kolozsi, Pál Péter, Csaba Lentner, and Bianka Parragh. “The Pillars of a New State Management Model in Hungary. The Renewal of Public Finances as a Precondition of a Lasting and Effective Cooperation Between the Hungarian State and the Economic Actors.” POLGÁRI SZEMLE: GAZDASÁGI ÉS TÁRSADALMI FOLYÓIRAT 14.Spec. (2018): 12-34.

Mohammadf, Faruque. “Effect Judicial Independence on the Foreign Direct Investment in South and South-East Asian Countries.” (2021).

Mukand, Sharun W., and Dani Rodrik. “The political economy of liberal democracy.” The Economic Journal 130.627 (2020): 765-792.

Ron, Oded, Mordechai Kremnitzer, and Yuval Shany (2020). Democracy in Crisis. The Israel Democracy Institute https://www.idi.org.il/books/32391 [Hebrew].

Voigt, Stefan, Jerg Gutmann, and Lars P. Feld. “Economic growth and judicial independence, a dozen years on: Cross-country evidence using an updated set of indicators.” European Journal of Political Economy 38 (2015): 197-211.