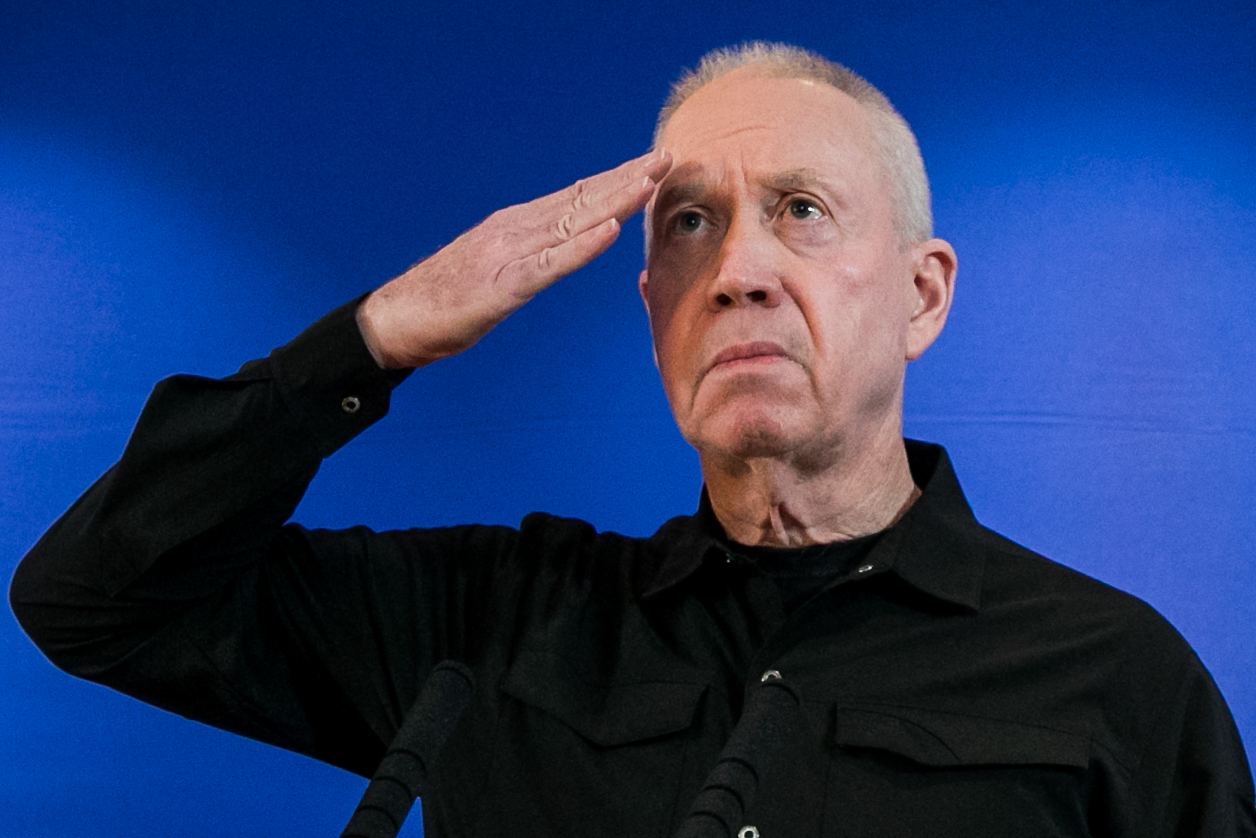

Minister of Defense Gallant is Fired: A Review of the Dismissal of Israeli Cabinet Ministers

At first glance, the dismissal of Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant is not unprecedented – prime ministers hold authority to fire ministers, and Prime Minister Netanyahu has done so in the past. However, the circumstances surrounding the current dismissal are especially intense.

Photo by Miriam Alster/Flash90

Over the years, the authority of the Prime Minister to remove ministers from their positions has become stronger. Who has fired the most ministers, and what were their reasons? Read on for the analysis.

The Grounds for Firing a Minister

The various grounds for firing a minister can be divided into two categories. The first category entails ousting a minister from the government because of actions or statements that constitute a violation of the principle of collective responsibility. According to this principle, which is a foundation of the parliamentary system of government, members of the government are entitled to express their opinion and even to vote against a proposal or policy raised by the prime minister within the cabinet, but from the moment the cabinet makes a decision, they must fall in line. In other words, if a particular decision was made by a majority of the cabinet members and it then comes up for a vote in the Knesset, all government ministers—including those who opposed it—are obligated to support it. If they feel that their conscience does not allow them to stand behind the decision, they should resign; if they do not resign, the prime minister is expected to fire them.

The second category of reasons for firing ministers includes grounds such as:

- Firing a minister because of a personal scandal in which the minister is involved

- Firing a minister because of the minister’s responsibility for the ministry’s erroneous policy or poor performance

- Firing a minister because of substantive disagreement with the prime minister’s policy

- Firing a minister because of a conflict with the prime minister that leads to a crisis in personal trust between them.

The Prime Minister’s Authority to Fire Ministers

Until 1962, Israeli prime ministers did not have formal authority to fire ministers. Ministers were able to violate collective responsibility without the prime minister being able to punish them.

Consequently, in such cases, prime ministers adopted the not-so-elegant solution of resigning and forming a new government without the insubordinate ministers. In 1955, for example, after the four ministers of the General Zionist party abstained in a no-confidence vote, Prime Minister Moshe Sharett submitted his resignation and formed a new government within 24 hours, with the very same coalition—except for those ministers. Four years later, ministers from Mapam violated collective responsibility. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion did not hesitate, submitted his resignation, and formed a new government without them.

In these early cases, ministers who violated collective responsibility were indeed punished and ousted from the government. But the need for the entire government to resign in order to enforce collective responsibility was seen as a convoluted and ineffective mechanism. For this reason, in 1962, the Knesset amended the Transition Law (Basic Law: The Government was only enacted six years later) to explicitly authorize a prime minister to fire a minister who votes against a cabinet decision in a Knesset vote or who abstains from such a vote. Relying on this amendment, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin fired the ministers of the National Religious Party (NRP) in December 1976, after two of them abstained in a motion of no-confidence. Similarly, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon exercised this authority in 2002, when he fired four Shas ministers after they voted in the Knesset against the economic emergency plan approved by the cabinet (some two weeks later, however, those ministers returned to their positions). Two years later, Sharon fired the Shinui party's five ministers after they voted against the state budget bill, and fired Minister Uzi Landau for voting in the Knesset against the disengagement plan approved in the cabinet.

Until 1981, the law was silent about firing ministers on grounds other than violation of collective responsibility. Prime ministers could not dismiss a minister because he or she was implicated in a scandal, for inadequate personal performance or inadequate performance of the ministry for which he or she was responsible, or because of a crisis of personal trust. In 1981, the Basic Law: The Government was amended to explicitly authorize the prime minister to fire a minister. Article 22B of the law stipulates: “The prime minister is entitled, after informing the government of his intentions, to remove a minister from his post.” The language of the law does not specify grounds and thus grants prime ministers broad discretion in such dismissals.

The first case of firing a minister for reasons other than violation of collective responsibility was in 1990. Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir learned that his finance minister, Shimon Peres, was trying to cobble together an alternative coalition. This disloyal conduct led to Peres’ dismissal, a move that quickly precipitated the resignation of the other Alignment ministers and comprised the opening gambit of the “stinky deal.” Nearly a decade later, Prime Minister Netanyahu fired his defense minister, Yitzhak Mordechai, for similar reasons of disloyalty. In the weeks preceding his dismissal, Mordechai, a member of Netanyahu's Likud party, openly adopted a critical tack vis-à-vis the prime minister, questioned his own future in the Likud, and even publically contemplated joining the Center Party that was just being formed. Netanyahu viewed this behavior as intolerable and fired him.

The prime minister who exercised the authority to fire ministers most widely was Ariel Sharon. In addition to the cases cited above, he fired three other ministers from his government in 2004. In one case, he fired Yosef Paritzky (Shinui), at the request of Partizky's faction, because of involvement in an internal party-political scandal. In a second case, he fired Ministers Avigdor Liberman and Benny Elon. The dismissals of Liberman and Elon raised considerable debate because they took place several days before a critical vote in the cabinet on the plan to disengage from Gaza.

In Sharon’s assessment, his proposed disengagement plan would not win the vote of a majority of the cabinet members; as a result, he fired the two ministers in order to secure the necessary majority. This move—firing ministers in order to win a majority in the cabinet—came under fierce criticism and even led to a High Court petition seeking to invalidate the dismissals. The court rejected the petitions, ruling that the prime minister has the authority to fire a minister because of his political views and that political considerations are not improper in a prime minister’s decision to fire ministers. This ruling further expanded the broad authority of prime ministers to dismiss members of their government, while simultaneously stating that "the prime minister's discretion is not unlimited. It is bounded by situations of extreme unreasonableness. If the prime minister's decision to dismiss a minister is extremely unreasonable, it will be unlawful, and the court will exercise its judicial review."

Table 1: Ministers Fired from the Israeli Government

|

|

Prime Minister |

Fired Ministers |

Party |

Grounds for Firing |

|

1976 |

Yitzhak Rabin |

Yosef Burg, Zevulun Hammer, Yitzhak Rafael |

National Religious Party |

Violating collective responsibility |

|

1990 |

Yitzhak Shamir |

Shimon Peres |

Alignment |

Disloyalty |

|

1999 |

Benjamin Netanyahu |

Yitzhak Mordechai |

Likud |

Disloyalty |

|

2002 |

Ariel Sharon |

Shlomo Benizri, Nissim Dahan, Eli Yishai, Eli Suissa |

Shas |

Violating collective responsibility |

|

2004 |

Ariel Sharon |

Avigdor Liberman, Benny Elon |

National Union–Yisrael Beiteinu |

Policy disputes |

|

2004 |

Ariel Sharon |

Yosef Paritzky |

Shinui |

Political scandal |

|

2004 |

Ariel Sharon |

Uzi Landau |

Likud |

Violating collective responsibility |

|

2004 |

Ariel Sharon |

Yosef Lapid, Avraham Poraz, Ilan Shalgi, Modi Zandberg, Victor Brailovsky |

Shinui |

Violating collective responsibility |

|

2014 |

Benjamin Netanyahu |

Tzipi Livni, Yair Lapid |

Hatnua, Yesh Atid |

Disloyalty (?) |

|

2019 |

Benjamin Netanyahu |

Naftali Bennett, Ayelet Shaked

|

Jewish Home / New Right |

Were not elected to the 21st Knesset

|

|

2022 |

Benjamin Netanyahu |

Aryeh Deri |

Shas |

Compliance with Supreme Court ruling |

Sources

- HCJ 5261/04 Fuchs v. Prime Minister of Israel

- Dowding, Keith and Patrick Dumont (eds.) (2009). The Selection of Ministers in Europe: Hiring and Firing, London: Routledge.

- Kenig, Ofer and Shlomit Barnea (2014). “Israel: The Choosing of the Chosen,” in Keith Dowding and Patrick Dumont (eds.), The Selection of Ministers around the World, London: Routledge, pp. 178–196.