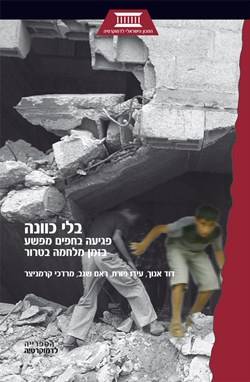

Collateral Damage

The Harming of Innocents in the War Against Terror

- Written By: David Enoch, Iddo Porat, Re’em Segev, Prof. Mordechai Kremnitzer

- Publication Date:

- Cover Type: Softcover | Hebrew

- Number Of Pages: 215 Pages

- Center: The Amnon Lipkin-Shahak Program on National Security and the Law

- Price: 65 NIS

What is the law regarding harm caused to civilians as part of a strike against a military objective that is a permissible target if the action is carried out, not with the intent to harm civilians, but with the awareness that such an outcome is possible, even highly probable? In this book, this question is explored from an ethical perspective by three legal theoreticians: Prof. David Enoch and Dr. Re'em Segev, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Dr. Iddo Porat, of the Ramat Gan Law School.

What is the law regarding harm caused to civilians as part of a strike against a military objective that is a permissible target if the action is carried out, not with the intent to harm civilians, but with the awareness that such an outcome is possible, even highly probable? In this book, this question is explored from an ethical perspective by three legal theoreticians: Prof. David Enoch and Dr. Re'em Segev, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Dr. Iddo Porat, of the Ramat Gan Law School. Prof. Enoch addresses the issue of awareness from a more general standpoint, while Drs. Segev and Porat focus on situations in which it is known that there is a high probability that a certain incident will take place.

An armed band of Palestinian terrorists is heading toward Israel from the Gaza Strip to carry out an attack. While still in Gaza, it enters a multi-story residential building. Is it permissible to attack the building in order to strike the group, thereby also harming the occupants of the building who are not involved in terror?

International law does not categorically prohibit the harming of civilians under such circumstances (often referred to as "incidental harm"), but it does forbid harming civilians to a degree that is disproportionate to the military advantage underlying the action. Even so, there is an absolute prohibition against the intentional harming of civilian non-combatants; hence the (almost) universal condemnation of acts of terror that target civilians.

What is the law regarding harm caused to civilians as part of a strike against a military objective that is a permissible target if the action is carried out, not with the intent to harm civilians, but with the awareness that such an outcome is possible, even highly probable? This question is explored from an ethical perspective by three legal theoreticians: Prof. David Enoch and Dr. Re'em Segev, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Dr. Iddo Porat, of the Ramat Gan Law School. Prof. Enoch addresses the issue of awareness from a more general standpoint, while Drs. Segev and Porat focus on situations in which it is known that there is a high probability that a certain incident will take place.

David Enoch's article analyzes the question of whether there is a moral and ethical difference between Palestinian terrorist attacks and the preventive assassinations (known as "targeted killings") carried out by Israel. After eliminating extraneous considerations, he examines whether the moral distinction between these actions is that between "intended consequences…and…consequences that, even if foreseeable, are unintended." More precisely, he states: "For the terrorist, the harming of innocent victims is a means to an end, whereas, for the person carrying out the targeted killing, the harming of innocent victims falls under the heading of a predictable incidental result." Enoch demonstrates that this distinction is central to common-sense moral thinking, in that it allows us to differentiate between two cases: the runaway train car scenario and the organ transplant scenario. In the first case, the re-routing of a train car that is about to kill five people onto a track where it is likely to kill one person is considered by us to be a morally justified act, in that the killing of one man is neither a goal nor a means to an end, but merely an expected, or predictable, incidental result. In the second case, the killing of one patient by a doctor in order to transplant his organs into several patients that he wishes to save is considered by us to be an unjustified action, since putting the patient to death, from the doctor's perspective, is a goal in itself, or at least a means to an end.

Enoch, however, offers numerous substantive criticisms of this distinction. The discussion of these criticisms can ultimately be reduced to the following complex position: on the one hand, the inability to defend the distinction mentioned above, and on the other, the statement that "the profound ethical revolution that would be engendered by the collapse of the above distinction causes me to avoid hastening to conclude that the distinction cannot be defended against the difficulties enumerated above (even if I do not know how to defend it)."

Enoch shifts at this point to discussing the special case of Israel's actions. His conclusion is that even if we assume the existence of a distinction between intended consequences and expected consequences, there is reason to reject such a distinction when the case involves the actions of a state. Ostensibly, such a position would hold the state to a stricter standard; but surprisingly enough, it lends itself to a more lenient approach vis-à-vis the state: in the case of the state, the balance is weighted in favor of considerations of actual outcome, whereas with regard to a terrorist, the preceding distinction still applies. It is not entirely eliminated, and serves as a moral barrier to acts of terror whose intent is to kill civilians. To avoid this asymmetry, Enoch raises the possibility of denying the moral relevance of the distinction between intended and expected consequences in the case of individuals as well.

Iddo Porat's article is a response to Enoch's remarks. Porat posits five major arguments, as follows:

(a) The case of the terrorist as discussed by Enoch does not reflect the typical case of the Palestinian terrorist in terms of its severity.

(b) There is reason to address only those cases in which it is understood that there is a high degree of probability that civilians will be killed, and not every case where the awareness exists of such a possibility.

(c) There is room to distinguish between responsibility for an action, which Enoch addresses, and justification for an action, which is the category according to which the actions of a state should be judged.

(d) It is possible to preserve the distinction between the case of the railway car and that of the transplant by differentiating between creating an unjustified risk and deflecting an existing risk from its original course, which can be justified.

(e) The distinction between intent and expectation can be preserved if we base ourselves on Kant, as follows: If we wish to act in accordance with the first formulation of Kant's categorical imperative, we would be expected to agree to a universal practice that permits the causing of expected (but not intended) harm in order to achieve positive results; but we would not agree to a general practice that allows the causation of intended harm for the purpose of achieving positive results.

In his response to Porat, Enoch offers a dissenting view concerning the moral relevance of the distinction between creating a new risk and deflecting an existing one. He shows that even if we were to accept this distinction, it would not offer us an ethical distinction between a state-sponsored act of killing and a terrorist action. Enoch also takes issue with Porat's "Kantian argument." He demonstrates, inter alia, that Porat's argument is based on an outcome-oriented calculation that can be contradicted, and that such a calculation cannot serve as the basis for an argument concerning the intrinsic importance of the distinction between intent and expectation. In addition, he argues that it is unjustified to limit the comparison between intent and expected outcome to cases in which the outcome is almost certain. He comments that Porat's discussion applies also to consequences that are totally unexpected, which are clearly outside the parameters of the present debate. Enoch demonstrates further that Porat's position on mental states is different and narrower than his, and that Porat's treatment of causal structures likewise differs from his own. That is, Enoch believes that Porat's approach embraces the notion of causal structure as well.

Re'em Segev focuses on a situation in which the harming of civilians is a certain, or highly probable, outcome. He takes a two-pronged approach: analyzing the issue in terms of outcome, and then examining whether there is room for a deontological (that is, non-outcome-oriented) limitation of such harm. After a thorough discussion of the issue, he concludes that "such actions would be justified only in cases in which the estimated number of casualties from a terrorist attack is much greater than the estimated number of casualties from an action taken to prevent it, or where there is a very high likelihood of preventing an attack."

In other words, Segev concludes that such actions would be justified only if the chance of saving innocent victims would be greater than the risk of harming innocent victims. He demonstrates that such a condition is not fulfilled except in outstanding cases, particularly since in general it is not certain (as opposed to merely suspected) that an act of terror is likely to be committed; there is no guarantee that the preventive action will succeed; and there is a chance to prevent the harming of innocent victims in a different way. By contrast, the risk of harming innocent victims in the scenario in question is certain, or virtually so. Segev shows that calculations based on outcome are liable to be weighted against innocent victims on the other side. Accordingly, his conclusion is that two possibilities apply here: one, utterly rejecting such actions; and the other, permitting them only in the rare cases in which "there is reliable evidence on which to base a reasonable assumption that if preventive action is not taken, an actual terrorist attack will be imminent."

In the second part of the article, Segev analyzes the possibility of adopting a deontological limitation on preventive action, and offers arguments for his conclusion that such an option should be rejected. In addition, he addresses the relationship between intended outcome and expected outcome, concluding that the distinction between the two should be negated and they should be seen as normatively equal.

The present abstract is part of an introduction written by Prof. Mordechai Kremnitzer of the Israel Democracy Institute and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Kremnitzer concludes that the most enlightened alternative would be to limit attacks on a military target, in situations in which there is a high probability that innocent victims will be killed in the course of the attack, and to cases of concrete danger in which there is a solid basis for believing that if preventive action is not taken, an actual terrorist attack will be imminent. He further concludes that this approach should be expressed in the form of a clearly defined principle.