Gotta Have Faith: The Knesset's Top Priority for 2017

Some years ago, a former IDF general and one of Israel's most esteemed technology innovators who had been elected to the Knesset logged into his new parliamentary inbox. He was surprised to discover dozens of messages labeling him corrupt, incompetent and lazy, among other “superlatives.” These greetings had been sent before he even began work as a duly elected Knesset member.

The 2016 Israeli Democracy Index, published at the end of the last calendar year, provides the figures that make sense of this story. While some of the data portrays Israel as doing OK or better, notwithstanding its numerous internal and external challenges, other statistics paint a bleak and disturbing picture of Israeli society's plummeting faith in its political institutions or elected officials.

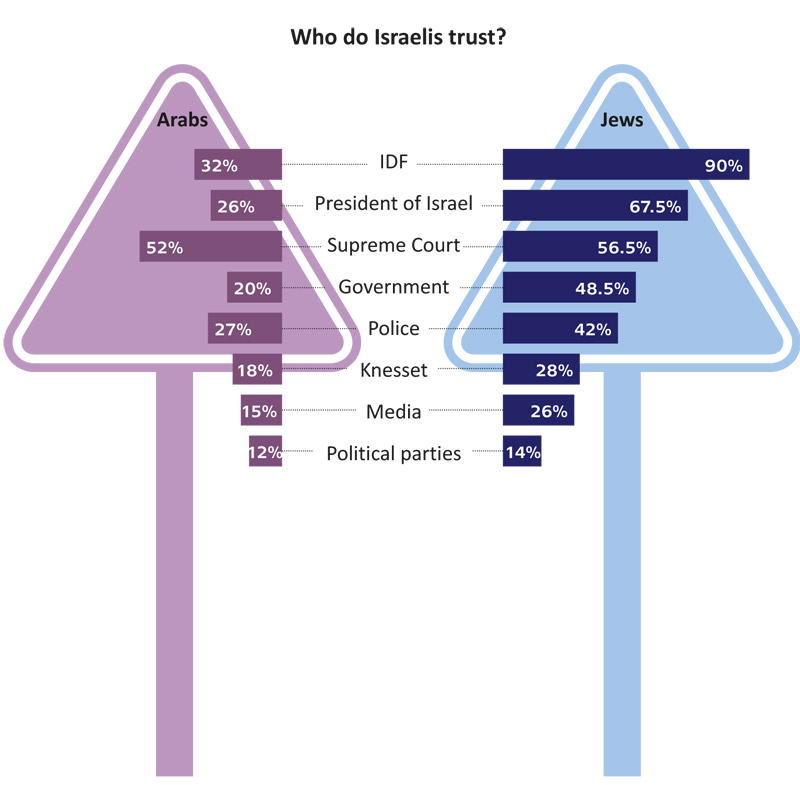

Jewish Israeli’s confidence in the Knesset specifically, and government in general, is less than 30 percent. Trust in the country’s political parties sank to 14 percent, down from 37 percent in 2013. These indicators are far below the average levels of trust the index has been documenting since 2003. And Arab Israelis have an even grimmer view of the country’s political institutions.

At the same time, when Israeli citizens were asked whether they have faith in their local banking institutions, the level of trust rose to 58 percent. In other words, the 2016 Israeli Democracy Index did not find that the public's faith in all institutions declined equally. Rather, it is the level of trust in political institutions that has deteriorated dramatically.

This lack of trust goes hand-in-hand with another compelling index finding, according to which there is a surprising national consensus (80%) across all parts of Israeli society – secular, religious and ultra-Orthodox Jews and Arabs –that, “Politicians look out more for their own interests than for those of the public who elected them.”

In Israel, such broad based agreement is exceedingly rare and is likewise reflected in the fact that the majority of index respondents do not believe that most Knesset members work hard and are doing their jobs. In addition, there is a widely held public perception that Israeli leadership tends to be corrupt. Finally, most Israelis do not think they have any influence over government policy.

Pandemic lack of trust in institutions and politicians are warning signs for the continued viability of Israel's democratic form of government, which is based in the final analysis on political efficacy. If we add to this the fact that Israel is ranked at the bottom of the “Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism,” part of the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicator, nestled somewhere alongside the country's Middle Eastern neighbors, we can no longer deny the need for serious and immediate change.

Accordingly, winning back the trust of the Israeli public should be one of the major challenges our elected officials take on in 2017.

Political and Electoral Reform

We know that high government turnover rates and short-sighted political strategies can significantly stifle economic growth, even in established democracies. The link between economic underperformance and low levels of public trust in government is also well documented. Therefore, one way to effect change would be to strengthen the weakest links of the Israeli political establishment: political parties and the Knesset. Bolstering these two institutions will help stabilize the entire political system, strengthen the government's ability to govern effectively, and boost public trust.

As I have suggested elsewhere, the key reform is to legislate that from now on the leader of the country's largest political party automatically becomes the head of the government. This seemingly small change would encourage the development of two major political blocs and forever sever the link between budgetary approvals and dissolution of the Knesset. It would also lead to reduced political instability.

This and other measures to strengthen the Knesset and political parties are reforms that, if implemented, would shrink the amount of political leverage currently held by small, sectorial parties. As a result, it is likely that the negative image that too many Israelis have of their elected officials would begin to improve.

Further, we must act to boost the public’s participation in party politics.

For one, I suggest we create a new membership model for political parties. This could happen in a number of different ways. One approach would be to increase the public’s involvement in party processes while simultaneously reducing the influence of pressure groups. To do so, we would need to consider a system of open primaries, whereby the wider public takes part in the election for the head of a party and/or its full Knesset list.

Obviously, if we move in this direction, we would need to establish filtering mechanisms for voters. One idea is to require that prospective voters make a minimum payment to the party or have them sign a pledge that they agree with the party's basic ideology. Such obligations would make it more difficult to sabotage a particular candidate or party by opposition from within.

At the same time, we must leverage the digital tools available to us today to boost public participation in politics. For example, we could enable the establishment of internet forums as alternatives to the parties' brick and mortar offices. Embracing the digital age in such a way would drive people to engage more regularly in the political process. Broadly speaking, we also need to combat the personalization of politics by growing party engagement on social networks, so that voters logging onto Facebook and Twitter don't only hear from individual politicians promoting their personal agendas.

Of course, these specific reforms will not miraculously solve the issue of good governance. New policies and protocols will help reverse negative trends, but are not, in and of themselves, the be all and end all.

Indeed, one reason why Israelis lack trust in the Knesset is because of the behaviors of certain individual MKs. For example, coalition chairman and Likud MK David Bitan continues to put his foot in his mouth, saying that the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was not a political murder; that he is tracking the Facebook posts of journalists and that he prefers that Israeli Arab citizens not vote at all. Bitan is just one example of a handful of new MKs who are consistently breaking new record lows and setting a bad example for the public.

Just last month, Arab-Israeli MK Bassel Ghattas (Joint List) was suspended for six months from all Knesset activities for smuggling cell phones, SIM cards and documents to prisoners convicted of terrorism.

Although structural reform may not prevent such personal antics, they would at least provide a solid start and some momentum to the changes needed to move Israel forward in 2017.

Toward a New Common Denominator

The personalization of politics and the fracturing of political parties feed off of what President Reuven Rivlin describes as Israel’s demographic reality: four disparate tribes. Although social realities are more nuanced, Rivlin is basically right that the old Zionist consensus has given way to a struggle among secular, national-religious, Arab and Haredi Israelis over the direction the ship of state should head in the face of grave foreign and domestic challenges, it is imperative for Israel's national survival that we find ways to foster the emergence of a broad civic denominator common to all of Israel's tribes.

We must restore that sense of the collective good summarized by the untranslatable Hebrew term “mamlakhtiyut.”

This is yet another reason why political reform is so vital. If we can rebuild the party structure around two large blocs that transcend sectorial interests, we will not only bring about more effective government but ensure that our elected officials act to further the common good. Among other elements, the new Israeli esprit de corps must build on some of the good news from the 2016 Democracy Index: 85 percent of Israelis agree that, “To deal successfully with the challenges confronting it, Israel must maintain its democratic character.” Moreover, the majority of Jewish and Arab Israelis are proud to be Israeli, feel they can rely on each other in times of trouble and are optimistic about their country’s future.

If the right steps are taken, Israel will not only begin to overcome its current challenges, but position itself for a bright and promising future.

Let’s act now to ensure that when Israel's future elected leaders enter the Knesset for the first time, their inboxes will be filled with congratulatory notes from engaged citizens eager to see them and their country succeed.

The writer is President of the Israel Democracy Institute and is a former member of Knesset (Kadima 2007- 2013). This article first appeared in the Jerusalem Report.