How to End Israel’s Political Impasse

Benjamin Netanyahu couldn’t form a government, because the electoral system is dysfunctional. The country needs to enact two simple reforms, or it will face perpetual stalemate.

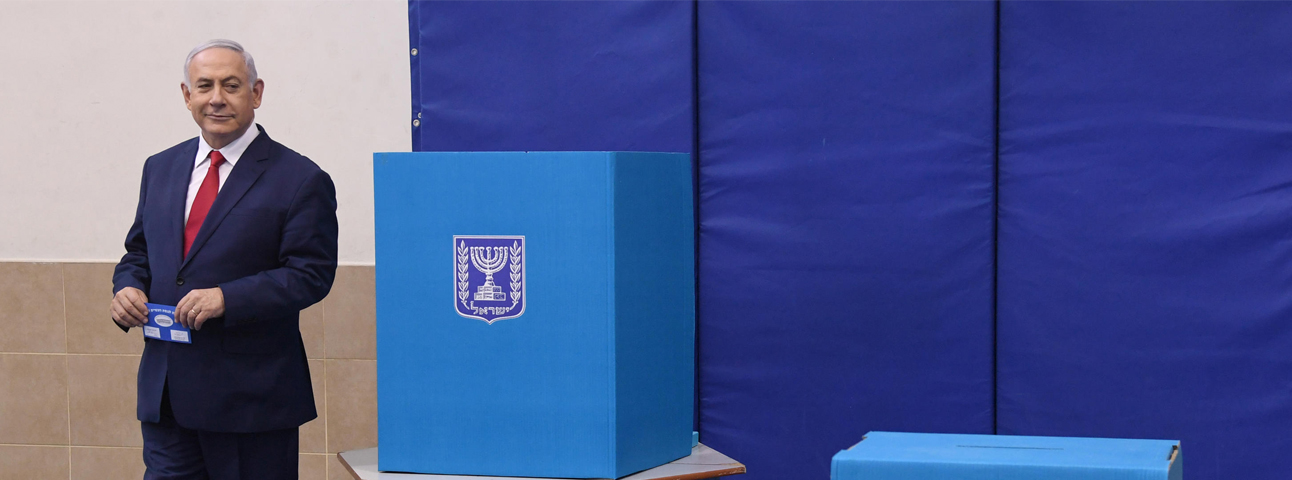

PM Netanyahu | Flash 90

Israel just experienced one of the worst political crises in its short history. Less than two months after voters went to the polls, coalition negotiations collapsed and the Knesset voted to dissolve itself, scheduling new elections for Sept. 17 at a cost of an estimated 1.8 billion shekels (half a billion dollars) in direct and indirect costs to taxpayers.

This mess could have been avoided if two simple political reforms had been implemented: The largest party in the Knesset would form the governing coalition and, once in place, the new government would not require a vote of investiture to begin its term. This coming November, when a new government is finally formed, these vital reforms must be the first thing on the agenda.

One Israeli leader foresaw this problem years ago. “We are splitting into little parties, none of which can lead the state, and this problem is getting worse,” he argued in a campaign speech in January 2015. “This has cost us billions, not just in election costs but as a result of the economic uncertainty and the lack of governability.” He then pledged to make electoral reform the heart of his agenda.

That leader was Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—and he worked with me and the experts at the Israel Democracy Institute on these reforms back in 2015. Last month, ignoring his own culpability in Israel’s current political chaos, Netanyahu compared his country to a parliamentary democracy that has become infamous for its instability and lamented this newest election, mockingly asking reporters, “Have we become what Italy once was?”

From the outset, Netanyahu placed significant handicaps in his own path and limited the number of potential coalition partners available for him to work with. In his previous administrations, Netanyahu successfully maneuvered between forming coalitions with his political base on the right and governments that included rivals from the center-left. But this time, by running for office despite the preliminary indictments already filed against him for bribery and other crimes and then insisting on a new immunity law and judicial reforms tailored to help him avoid trial, Netanyahu had no room for error. When former Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman’s demands for changes in the military draft laws clashed with the ultra-Orthodox parties’ unwillingness to budge, a perfect political storm erupted.

Still, an effort to address the institutional weaknesses inherent in Israel’s electoral system could have stopped it. Israel’s unique system includes a proportional representation system with a relatively low electoral threshold for parties to enter the parliament: 3.25 percent of votes. This gives multiple small, single-interest parties veto power over ruling parties, ensuring vulnerable coalition governments. In fact, political fragmentation has always been an issue in the Israeli Knesset and has only worsened in recent decades. This can be measured by assessing the number of so-called effective parties in each term, meaning a weighted index of the number of parties represented and their relative share of the parliament’s seats. In the 1950s, there was an average of about five effective parties in each Knesset term. The number rose over the years with a peak of almost nine in the late 1990s, and over the past decade, the average has been over seven effective parties per term. The result of this fragmentation is also apparent in the relatively short terms of each Knesset, with the last Israeli parliament to serve its full term without an early election from 1984 to 1988.

Despite these electoral imperfections, the tough neighborhood it exists in, and constant internal and external challenges, Israel has persisted as a free democratic society for 71 years. In other words, the system works for the most part. But the country desperately needs electoral reform to make it work more efficiently and to avoid crises like the current one.

Some reforms have been tried in the past, such as implementing a direct vote for the prime minister that resulted in further fragmentation in the Knesset. Others, such as raising the electoral threshold, as was done when it was increased from 2 percent of votes to 3.25 percent in 2015, succeeded in limiting the incentives for the smallest parties to run while at the same time safeguarding the representativeness of the country’s minorities. This did not, however, stop midsize parties from continuing to threaten the stability of governments in return for a disproportionate focus on their narrow agendas.

Other potential reforms, such as adopting electoral districts or implementing a semi-open electoral system in which voters decide the makeup of their preferred slate for the Knesset on Election Day, seem likely to improve the efficiency of Israeli governments, but they would take significant political will on behalf of the existing parties and probably years to implement. Alternatively, the reforms proposed below are evidence-based and practical to implement, and they could likely garner enough support to pass the Knesset.

First, the head of the party that wins the largest number of seats in the election should automatically be granted the mandate to form Israel’s government. Currently, the country’s president tasks the member of parliament they think has the best chance of succeeding with assembling a coalition. This member must then come back to the president within 42 days and present them with a governing coalition of at least 61 members. This proposed change would limit the ability of smaller parties to politically blackmail the appointed prime minister, as the prime minister would begin their term without the parties’ agreement to sit in a coalition and the only real threat they could pose to the new government would be a so-called constructive vote of no confidence, where they persuade an absolute majority of the Knesset (61 members) to support an alternative candidate for prime minister.

In today’s situation, Lieberman’s party’s unwillingness to join the coalition would not have stopped a fifth Netanyahu government from being formed. Instead, Netanyahu could have formed a stable minority government that could not be toppled, though he may have had to build ad hoc coalitions to pass specific pieces of legislation.

This reform would likely nudge Israel toward a parliament made up of two main political parties along with a much smaller number of satellite parties. In some ways, this theory was successfully tested in April’s election when both Netanyahu and Benny Gantz—the chair of the rival Blue and White party—campaigned by telling voters that the head of the largest elected Knesset list would form the next government. This was not necessarily true, but it was enough to increase their support among voters and result in the highest number of seats the Knesset has seen for two parties since the early 1990s. If this proposal were actually implemented, the percentage of the parliament the two parties would hold could be expected to increase significantly.

Second, Israel must do away with the parliamentary investiture vote where, after the prime minister presents a coalition to the president, an absolute majority of 61 members must vote in the Knesset in favor of beginning the government’s new term. Instead, after the head of the largest party formed a coalition, the new government would get right to work—avoiding the sort of posturing and unreasonable demands too often proposed by potential coalition partners. At least nine European countries with strong parliamentary systems already do not have such votes of investiture. If this rule had been in place, Lieberman’s refusal to provide his party’s five votes to Netanyahu would not have forced the country to face a destabilizing, and quite costly, election for a second time this year.

Today’s situation in Israel—in which a prime minister facing near certain indictments was too weak to form a government—is unusual. However, candidates across the political spectrum should see it as a wake-up call. Instability is damaging Israel’s economy and could have real implications for its security.

This is not an issue upon which the right and left in Israel should be divided, but rather an opportunity for them to work together to ensure a more stable, efficient, and effective government for all Israelis. Israel’s leaders should seize this opportunity now so citizens don’t find themselves heading to the polls once again just months after September’s elections.

The article was first published in Foreign Policy.