Changes in the New Labor Market: A Tasks and Skills Analysis

The rapid rate of technological development requires an examination of the changes in demand for workers, specifically in terms of the tasks that make up different occupations. This study offers such an examination along with recommendations for action

Flash 90

Executive Summary

Labor markets around the world have experienced huge changes over recent decades. The rapid rate of technological development, particularly- mechanization and digitization, as well as accelerated globalization, have affected the level of demand for workers in a wide range of industries and occupations. These changes have greatly benefited some workers, but have left others far behind. The growing gaps between these groups have resulted in a growing public discourse on the need to upgrade workers’ skills and adapt them to the tasks which are needed in the changing labor market. However, effectively designing policies to achieve this goal represents a major challenge at a time when it is not at all clear which tasks workers will have to perform in new jobs in the coming years, and accordingly-what skills they will need.

Much of the focus of this discussion is centered on the threat of the "disappearance" of certain occupations as a result of the increasing ability of automated mechanisms to replace human workers in performing various tasks. Yet even in many occupations that are not under threat of disappearing, the types of tasks required in the labor market are changing. Thus, preparing workers for the job market of the future requires an examination of the changes in demand for workers, specifically in terms of the tasks that make up different occupations. This study offers such an examination, by analyzing each occupation as a collection of tasks which are needed to different degrees with, and looks at the demand for different tasks, with the aim of characterizing and understanding changing trends in the Israeli labor market. By using a unique database that includes detailed information on the tasks required in each occupation, and combining it with administrative databases on workers in the Israeli workforce over a period of two decades, this analysis produces several new findings.

First, we found that since the turn of the century, there has been a sizable increase in the share of cognitive tasks required in the local labor market, particularly those that demand analytical thinking (which is central to professions such as engineering, software development, and financial consulting), and to a lesser degree in the share of cognitive interpersonal tasks (demanded of managers in the field of professional services or registered nursing). By contrast, over the last two decades the share of workers whose main tasks are manual and physical in nature, has declined by a third, from 30% of the market to 20%. Concurrently, there has also been a sharp drop l in the intensity of routine tasks at work, whether routine cognitive tasks (such as those required of clerks and cashiers) or routine manual and physical tasks (such as those of machinery operators or metalworkers). An analysis of the factors driving these changes shows that the dominant component is the change in the job composition of the labor market as a whole rather than changes in the mix of tasks characterizing each specific occupation .

The change in tasks required in the labor market has had an uneven effect on different population groups. Particularly noticeable has been the fact that this change has increased gaps between Jews and Arabs: Not only are Jews employed to a greater extent in occupations based on non-routine cognitive tasks—which are better paying occupations—but in addition, the differences in the tasks that characterize workers in each sector have grown over the last two decades. Considerable gender differences have also emerged regarding the task profiles of male and female workers. Thus, for example, the period examined has seen a clear decline in the proportion of men working in occupations that require physical tasks, and a parallel decline in the proportion of women employed in jobs involving routine cognitive tasks (such as clerical jobs).

The findings indicate that the type of tasks that workers perform can predict differences both in wages and in employment stability, beyond the impact attributable to workers’ level of education. Workers with similar education levels who differ in the tasks that characterize their occupations will likely have very different incomes. In 2019 for example, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic began, there was a wage difference of 27% between workers separated by one standard deviation in the required intensity of cognitive analytical tasks in their respective occupations. The same differentiation in the intensity of cognitive interpersonal tasks is correlated with a wage difference of 17.8%. By contrast, a standard of deviation of one, in the intensity of physical tasks correlates with a drop in income of 15.3%. These gaps demonstrate the strong correlation between the characteristics of the tasks required in a given occupation and worker productivity, with the differences between them also translating into large differences in wages.

These implications of the changes in the labor market also hold true for individuals' employment possibilities. The findings indicate a clear link between the intensity of routine tasks in an occupation and the probability that workers in that occupation will lose their jobs or move to another line of work within a three-year period. By contrast, workers in an occupation involving cognitive, analytical tasks have a significantly lower probability of losing their job or moving to another area of employment. These findings demonstrate the importance of the task characteristics of occupations for employee welfare and job security.

The collection of findings presented in this document shed light on the inherent potential of a task-based approach to analyzing changes in the labor market. Moreover, this approach helps us understand the sources of economic differences between groups of workers, and offers a better foundation for systemic thinking about the steps necessary to improve worker employability and productivity in the coming years.

Over the last two decades, there has been a major change in the composition of tasks in the economy as a whole. This change stems mainly from changes in the occupations in which workers are employed, a factor that explains over 90% of the difference on average.

A couple of the graphs that were included in the full survey:

Occupations by intensity of tasks

| Task | Occupation | Employees 2019 | Relative change in employees 2012–2019 | Real annual wage (NIS) 2019 | Relative change in real wage 2012–2019 |

| Non-routine cognitive analytical | Physicists, astronomers, chemists etc. (211) | 6,749 | -16% | 229,916 | 15% |

| University lecturers (231) | 22,497 | -11% | 215,350 | 10% | |

| Economists, sociologists, psychologists, rabbis etc. (263) | 83,239 | 44% | 166,374 | 26% | |

| Biologists, zoologists, etc. (213) | 14,462 | 32% | 205,914 | 36% | |

| Engineers (214) | 61,706 | 26% | 262,925 | 18% | |

| Non-routine cognitive interpersonal | CEOs (112) | 40,173 | 0% | 415,528 | 15% |

| Managers in health services, education, finance (134) | 73,919 | -14% | 242,021 | 6% | |

| Commercial managers (142) | 18,962 | -31% | 170,586 | 30% | |

| Business and administration managers (121) | 26,354 | -44% | 293,581 | 10% | |

| Qualified nurses (222) | 38,888 | 0% | 189,310 | 23% | |

| Routine cognitive | Cashiers (523) | 14,784 | -18% | 61,408 | 35% |

| Bookkeeping, financial, and wage clerks (431) | 26,996 | 11% | 123,213 | 16% | |

| Bank tellers (421) | 23,783 | -11% | 154,576 | 18% | |

| Medical and pharmaceutical technicians (321) | 10,284 | -22% | 152,603 | 25% | |

| Office clerks (411) | 21,533 | -27% | 94,116 | 14% | |

| Routine manual | Machinery operators in rubber, plastics, and paper production (814) | 9,320 | -24% | 110,452 | 15% |

| Metalworkers and die casters (722) | 10,284 | -14% | 140,981 | 19% | |

| Machinery operators in food production (816) | 8,035 | 0% | 108,010 | 13% | |

| Print workers (732) | 5,785 | -22% | 144,329 | 19% | |

| Unskilled construction and mining workers (931) | 8,356 | -24% | 57,922 | 6% | |

| Non-routine manual and physical | Truck and bus drivers (833) | 69,420 | 9% | 139,050 | 30% |

| Unskilled construction and mining workers (931) | 8,356 | -24% | 57,922 | 6% | |

| Mobile plant operators, e.g., cranes and tractors (834) | 20,569 | -14% | 151,146 | 30% | |

| Motor vehicle drivers, incl. vans and motorbikes (832) | 33,424 | -20% | 86,165 | 28% | |

| Unskilled delivery and warehouse workers (933) | 21,854 | 21% | 79,410 | 34% |

Changes in task composition in the Israeli labor market, 2001–2021

Note: The figure shows the change in the intensity of the five types of task for the entire economy between 2001 and 2021. NRCA—Non-routine cognitive analytical; NRCI—Non-routine cognitive interpersonal; RC—Routine cognitive; RM—Routine manual; NRMP—Non-routine manual and physical. Source: Central Bureau of Statistics and O*NET, authors’ own processing of data.

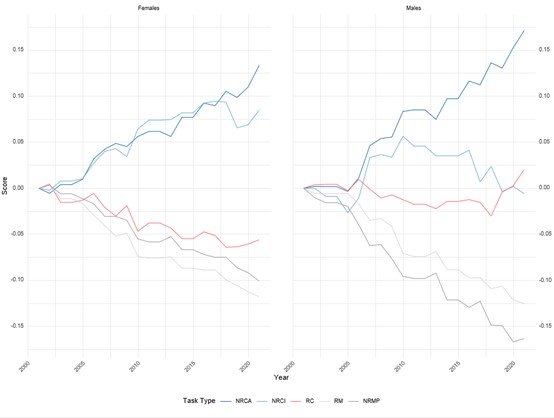

Percentage change in average task composition in the Israeli labor market, by gender

Note: The figure shows the change in the intensity of the five types of task for the entire economy between 2001 and 2021, by worker gender. NRCA—Non-routine cognitive analytical; NRCI—Non-routine cognitive interpersonal; RC—Routine cognitive; RM—Routine manual; NRMP—Non-routine manual and physical. Source: Central Bureau of Statistics and O*NET, authors’ own processing of data.

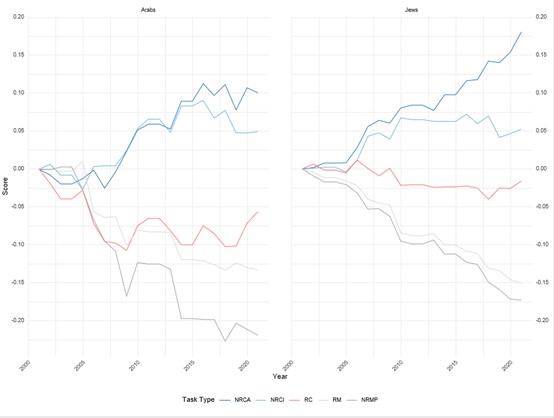

Percentage change in average task composition in the Israeli labor market, by sector

Note: The figure shows the change in the intensity of the five types of task for the entire economy between 2001 and 2021, by sector. NRCA—Non-routine cognitive analytical; NRCI—Non-routine cognitive interpersonal; RC—Routine cognitive; RM—Routine manual; NRMP—Non-routine manual and physical. Source: Central Bureau of Statistics and O*NET, authors’ own processing of data.

Conclusion and Implications

This study offers an analysis of trends in the labor market regarding changes in the tasks demanded of workers. While the accepted view of the labor market focuses on occupations or on workers’ level of education, an analysis by tasks reveals several important phenomena for understanding the shifts that have taken place in recent decades. These findings include a sharp rise in the intensity of cognitive analytical tasks required of workers, as well as in cognitive interpersonal tasks. In parallel, there has been a sharp decline in the share of jobs in which the main tasks required are routine, whether routine cognitive tasks or manual activities. In addition, there has been a fall in the proportion of jobs requiring physical labor.

Analysis of the factors behind these changes indicates that they stem mainly from changes in the composition of jobs, and less from changes in the combination of tasks that characterize the occupations themselves. Similarly, it appears that intergenerational differences have a sizeable impact on the accumulated composition of tasks: The occupations of workers now entering the labor market are different from those of the workers now retiring from it, and consequently the task composition of the market as a whole is changing.

There are two main reasons why it is important to identify these changes and understand the factors behind them. First, as we have shown, there is a strong empirical association between the characteristics of tasks and workers’ earning potential, as well as their future employment prospects. Thus, for example, workers with similar characteristics in all other aspects, including level of education, will earn very different salaries depending on the task intensity required for them to do their jobs. Occupations requiring more cognitive analysis pay a lot more (almost 25% more for each unit increase in the measure), while occupations with a physical component pay less (a “levy” of 13.5% for each unit increase in the measure). This finding reflects the strong coefficient between the task characteristics of the occupation and the workers’ level of productivity. Task characteristics also clearly predict the individual’s employment stability, both in terms of the probability of keeping their job and the probability of moving to a job in a different employment sector.

The second reason why these findings are important is that the changing trends in the tasks required in the labor market have had an uneven impact on different population groups. In particular, it is noticeable that the change in the mix of tasks has increased gaps between Jews and Arabs: Not only are Jews employed to a greater extent in occupations based on non-routing cognitive tasks—occupations that pay higher wages—but the differences between the tasks that characterize the workers in each sector have grown larger over the last two decades. From a gender perspective, too, there are large differences in task characteristics between male and female workers, though these differences lessened somewhat over the period studied. Finally, younger and middle-aged workers are experiencing changes in task composition in a way that is not seen among older workers (aged 55+). This difference seemingly stems from less frequent changes in occupation among the older age group.

An important limitation of the data we have is that they offer a picture of the current task composition for workers in practice, but not of the task composition that employers would choose if they were not restricted by the supply of workers’ skills. It is very much possible that employers would choose to create more jobs with certain task characteristics if there were more workers available with the necessary skills. This limitation restricts our ability to clearly determine what skills are truly required in the labor market at a certain time. However, the analysis presented in chapter VII shows that there is a clustering of the wage premium that characterizes the different tasks. This finding is consistent with the expectation that more and more workers will acquire the skills required by employers, which will help reduce the gap between supply and demand. At the same time, despite this finding, it is difficult to conclude from the data whether the changes in workers’ skills are happening quickly enough.

The clear trend of growing intensity of demand for cognitive analytical and cognitive interpersonal tasks in the job market, alongside falling demand for work involving routine tasks, highlights the need to train workers with the skills required to carry out this new composition of tasks. Much attention has been given in recent years to the challenge of equipping workers with the skills appropriate to the demands of the market, and this is not the place to review the extensive literature on this subject (for more details, see Eisenberg & Selivansky Eden, 2019). However, several of the findings in the literature are relevant to a discussion of worker skills in Israel.

First, instead of traditional methods of education, which have been found to improve skills such as rote learning and solving routine problems, there should be a transition to more modern methods directed toward developing complex problem-solving skills and reasoning capabilities. These modern methods include learning in groups, linking material studied with daily life, and highlighting the multiple ways of solving a given problem (Bietenbeck, 2020). There is also a need for pedagogies involving project-based learning and investigation, particularly those that require and encourage curiosity, creativity, and collaboration. In addition, there should be greater use of digital tools, both because of their effectiveness for studying the necessary content, and because they accustom students to working in a technological environment, which is what they will face outside the education system (Eisenberg & Selivansky Eden, 2019).

Finally, the lengthening careers of workers, alongside the changing nature of the skillsets required by the labor market, exacerbate the problem that skills and capabilities acquired by workers in the past become less relevant over time. As we show in chapter IX, changes in the task composition of the labor market are mainly related to the turnover of individuals in the market (that is, retirement of older workers and entry of new workers with new skills). Similarly, the findings presented in chapter X demonstrate that the change in task composition among older workers is particularly low. The problem of skills becoming outdated means that states must allocate resources to lifelong learning; that is, they must invest in national systems and programs that not only allow people to gain skills before they enter the labor market, but also throughout their working lives. These include the secondary education system and the higher education system, but also training and retraining programs for workers, as well as mechanisms for incentivizing employers to create options for on-the-job training. Learning of this kind is a vital element in the development and updating of worker skills over time, and is essential for responding to the changes in the tasks required by employers.