An Elections for the 25th Knesset: An Analysis of the Results in the Arab Sector

This review analyzes voting patterns among Arab citizens in the elections for the 25th Knesset, held on November 1, 2022. The graphs and tables are based on an analysis of the final results, as published by the Central Elections Committee.

Arab Turnout in Knesset Elections: A Balance Sheet of the Past Decade

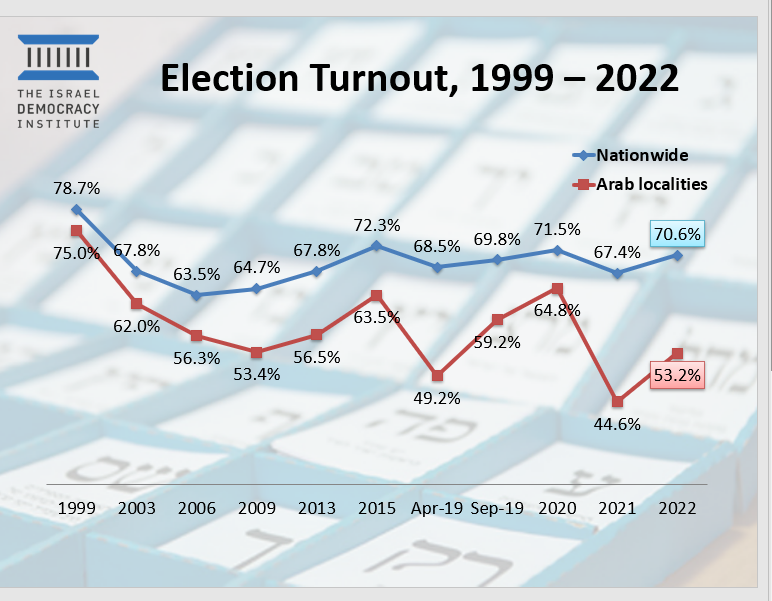

In the elections for the 25th Knesset, turnout by Arab and Druze voters stood at 53.2%—significantly higher than the low point recorded in the elections the previous year (44.6%). Looking at the past ten years (2013–2022), something new appeared in the last elections: This was the only occasion in which there was a significant rise in Arab turnout for Knesset elections, even though the parties were not running together, as they had under the rubric of the Joint List.

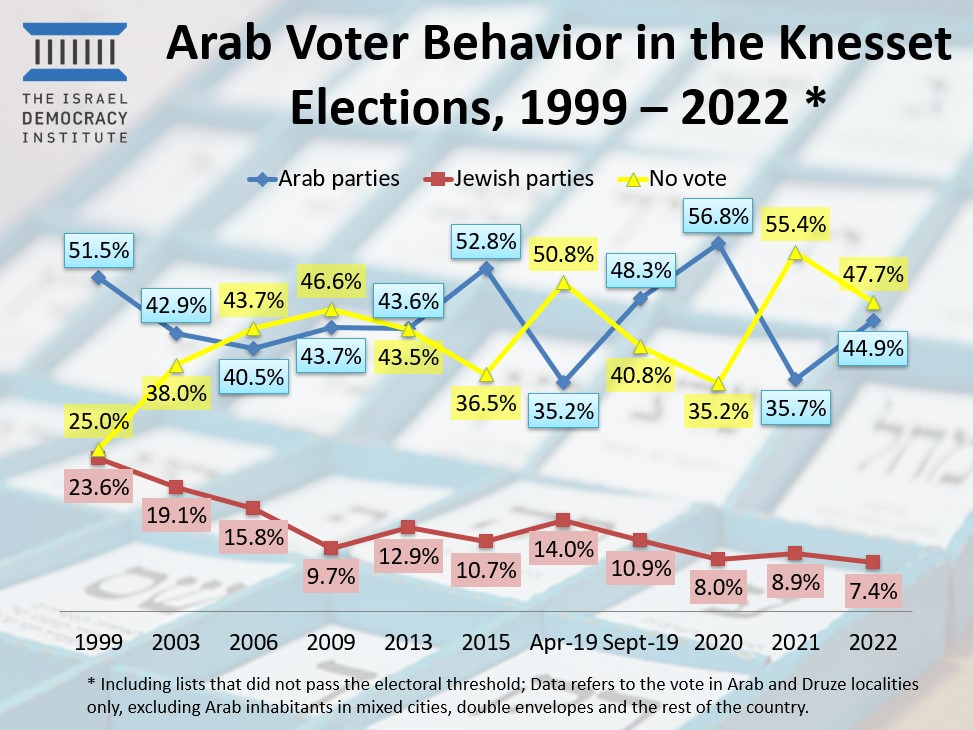

This graph indicates that the fragmentation of Arab politics into three separate lists composed of four parties did not deal a blow to Arab turnout; quite the contrary. A more thorough analysis of the political behavior of all eligible Arab voters in the last elections, as compared with the elections of the past decade (2013–2022), leads to an unambiguous conclusion: In these elections, the support for Arab parties by all eligible voters (both those who went to the polls and those who stayed home) in Arab localities, 44.9%, was the strongest in a decade, as compared to the previous elections when there were multiple Arab lists. Until this election, the peak under these conditions was in 2013, when three independent Arab lists competed, and support for the Arab parties by all eligible voters in Arab localities stood at 43.5%. In every other election in those years in which there was a split among the Arab parties, the rate of stay-at-homes in Arab localities was significantly higher than the number of those who did go to the polls. As noted, in 2022, we witnessed a new and contrary trend.

Nevertheless, Arab turnout (53.2%) remained low, and even slightly below the average for all elections in the past decade (2013–2022), 55.9%. Despite the increased turnout, the picture is clear: Half of all eligible Arab voters did not go to the polls on Election Day.

The Arab Parties’ Achievements

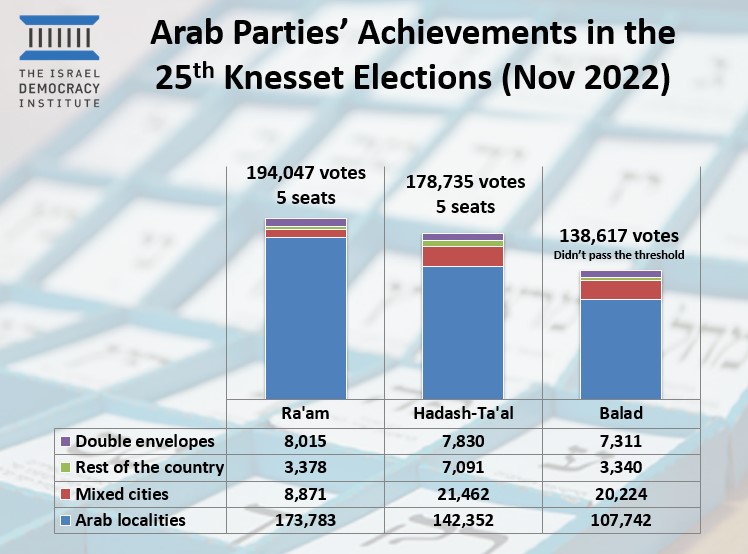

Three lists, comprising the four main parties that have been active in the Arab sector for more than two decades, contested the elections for the 25th Knesset: Ra’am, Hadash-Ta’al, and Balad. Thus, Arab politics returned to the threefold structure of 1999–2013, before the era of unity and alliances among the four Arab parties that began in 2015 with the establishment of the Joint List, after the electoral threshold was raised from 2% to 3.25%.

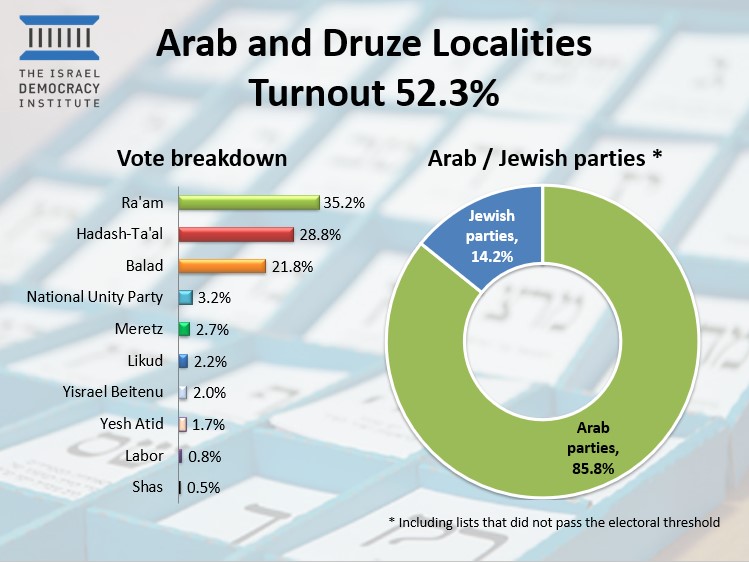

In the last elections, Ra'am became the leading party on the Arab street. It won five seats in the Knesset, the same number as Hadash-Ta’al, but garnered significantly more votes in Arab and Druze localities (35.2% of the total) than the other two Arab lists, Hadash-Ta’al (28.8%) and Balad (21.7%). Ra'am's dominance is shown by the fact that its vote total in Arab and Druze localities only (173,783), not including the mixed cities, double envelopes, and non-Arab localities throughout the country, sufficed for it to pass the electoral threshold. As in the previous elections (2021), this time as well, the Negev was one of the main bastions of support for Ra'am, awarding it the equivalent of 1.5 Knesset seats.

The Hadash-Ta’al list also won five seats: four for Hadash and one for Ta’al. It consolidated its dominance in the north, both in Arab localities and in the mixed towns in the region (Haifa, Acre, Ma’alot-Tarshicha, and Nof Hagalil). Hadash-Ta’al also garnered significant support in cities with a mainly Jewish population. In fact, the total vote in these localities (7,091) exceeded that of the other two Arab lists combined (Ra’am, 3,378; Balad, 3,340). We may assume that the overwhelming majority of the votes for the three parties in localities with a predominantly Jewish population, came from Arabs who live in Jewish cities but Hadash-Ta’al also picked up a sizable number of votes from Jews, mainly those who support Hadash.

Balad failed to clear the electoral threshold. For the first time since 1996, when it first ran for the Knesset, it was left on the sidelines. Nevertheless, its overall share of valid ballots (2.9%) was its best showing ever, and it missed entering the Knesset only by a thread. Its main bastion of support was found in the mixed cities in central Israel, especially Lod. In the Triangle region, it ran neck-and-neck with the other two Arab lists. Balad stumbled in the North and the Negev; its relatively weak support there lies behind its failure this year.

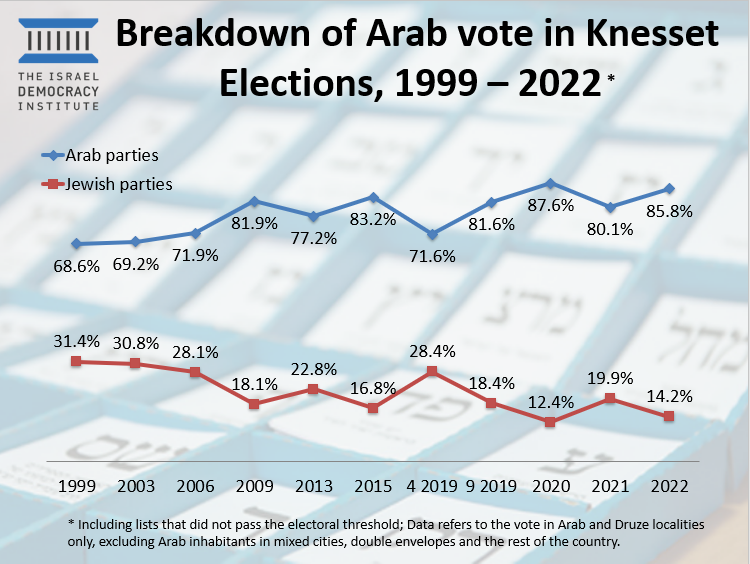

Taken together, the three Arab lists won 85.7% of the vote in Arab localities. It is noteworthy that overall support for the Arab lists was the strongest since the Joint List peaked in the elections for the 23rd Knesset (March 2020), when it gained the support of 87.6% of those who voted in Arab localities. Had turnout in the recent election approached 60% (as was the case in September 2019, when the Joint List was reconstituted), and given that the vast majority of those who go to the polls vote for Arab lists, Balad would probably have cleared the electoral threshold.

The Jewish Parties' Performance on the Arab Street

The Jewish parties picked up very few votes—only 14.3% of the votes cast in Arab localities. This is another example of the continuing decline in their support among Arab citizens, which has been falling consistently. In recent years, support for Jewish parties among all eligible voters in Arab localities (voters and nonvoters) has not exceeded 10%. In many respects, the Jewish parties are no longer a relevant political option for Arab voters.

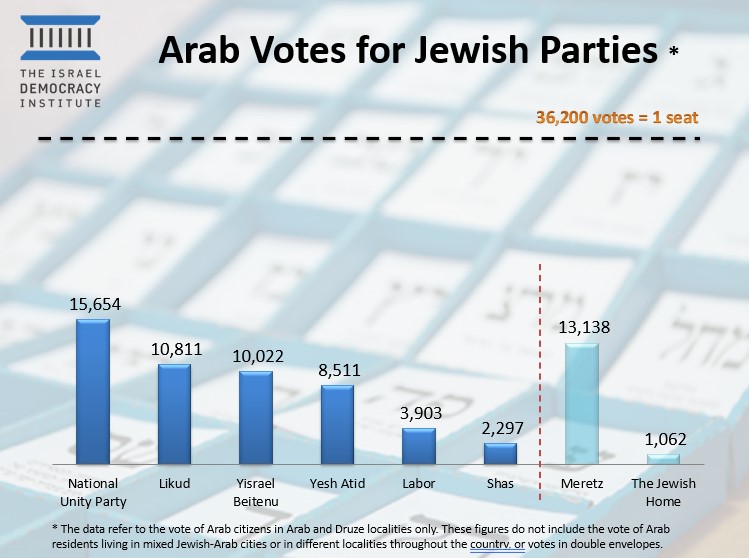

The following comparison is the primary example of this development. In the elections for the 21st Knesset (April 2019), when there was deep division among the Arabs due to the first breakup of the Joint List, support for Jewish parties among those who went to the polls in Arab localities soared to 28.4%. At that time, the ballots cast by Arab voters in Arab localities gave Jewish parties votes that were equivalent to more than three Knesset seats. The major beneficiary was Meretz, which made it past the electoral threshold only thanks to the Arab vote. By contrast, in the recent election, when the Joint List had permanently disintegrated and the Arab parties ran separately, support for Jewish parties in Arab localities was equivalent to less than two Knesset seats.

In the last elections, the National Unity Party enjoyed the strongest support among Arab voters (3.2%), more than 15,000 votes, most of them (11,000) in Druze localities. Nevertheless, the overall number of votes it received was equivalent to less than half a Knesset seat. Meretz, too, picked up significant support in Arab localities—about 13,000 votes, or 2.7% of the total, which would have brought it one-third of a Knesset seat had it cleared the threshold. The Likud (2.2%) and Yisrael Beitenu (2.0%) also picked up roughly one-third of a Knesset seat from Arab localities, while the support for Yesh Atid (1.7%) was worth a quarter of a Knesset seat. In the last elections, Labor and Shas, which once enjoyed substantial support in the Arab sector, trailed far behind.

Arab Voting Patterns

The Arab sector is not monolithic. Its voting patterns are linked to basic demographic variables, such as area of residence and religious identity. Voting is also influenced by social norms that dictate political behavior, such as support for a hometown candidate. This favorite son pattern is reflected in the especially strong support for a candidate who lives in a particular locality or region, due to local voters' desire for representation of one of their own in the Knesset.

Below, we survey the voting patterns of Arabs who went to the polls on Election Day, broken down into five geographic regions: The North, the Triangle, the Jerusalem Corridor, the Negev, and mixed cities .

The North

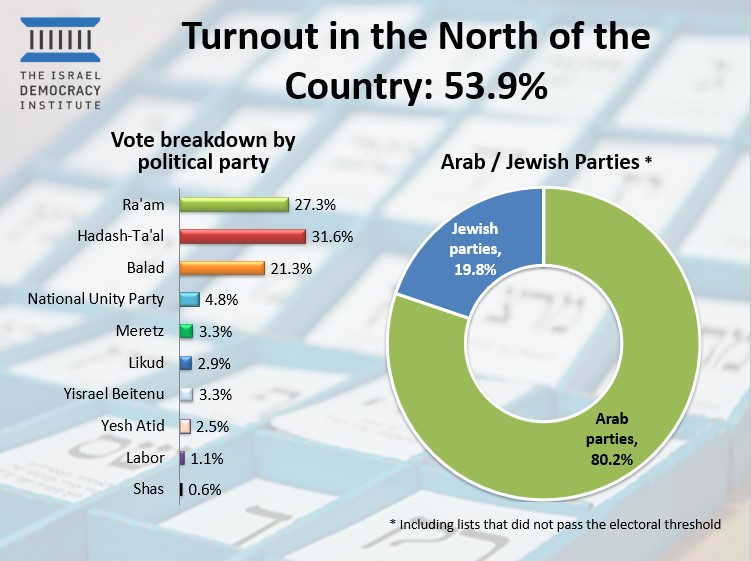

Turnout in the north—the Galilee, the northern valleys, Mount Carmel, and the northern coastal plain—stood at 53.9%. This region, which is home to more than 60% of all eligible voters in Arab and Druze localities, has long been seen as the cradle of the political and national identity of Israeli Arabs. Here Hadash-Ta’al enjoyed relatively strong support (31.6%), outpolling Ra’am (27.3%) and Balad (21.3%). In the historical centers of support for Hadash, including the Nazareth metropolitan area and the Sakhnin valley, support for the Hadash-Ta’al list led the pack, with an average of 40%.

Turnout was especially strong in several large urban communities in the Galilee, such as Sakhnin (68.4%), Majd al-Kurum (66.7%), Kafr Manda (65.2%), Tamra (63.5%), and Arrabe (56.9%). On the other hand, turnout was much lower in the two largest Arab towns in the north, Nazareth and Shefar’am—48.3% and 51.5%, respectively. Turnout was particularly low in Maghar, only 44%, which is somewhat surprising given that the chair of Ra’am, Mansour Abbas, is a Maghar resident.

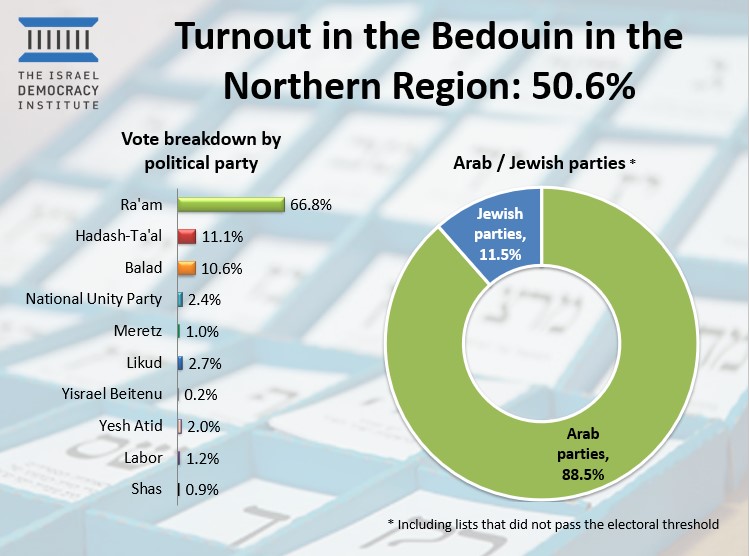

An analysis of voting patterns in the North reveals significant differences related to voters' ethnic and religious identity. In Bedouin localities in the North, the overwhelming winner was Ra’am, with 68.8% of the vote; Hadash-Ta’al and Balad did much worse (11.1% and 10.6%, respectively). Ra’am's strength among the Bedouin in the north can be explained by the inclusion of Yasir Hujeirat (formerly the council head of Bir al-Maksur) in the fifth slot on its list.

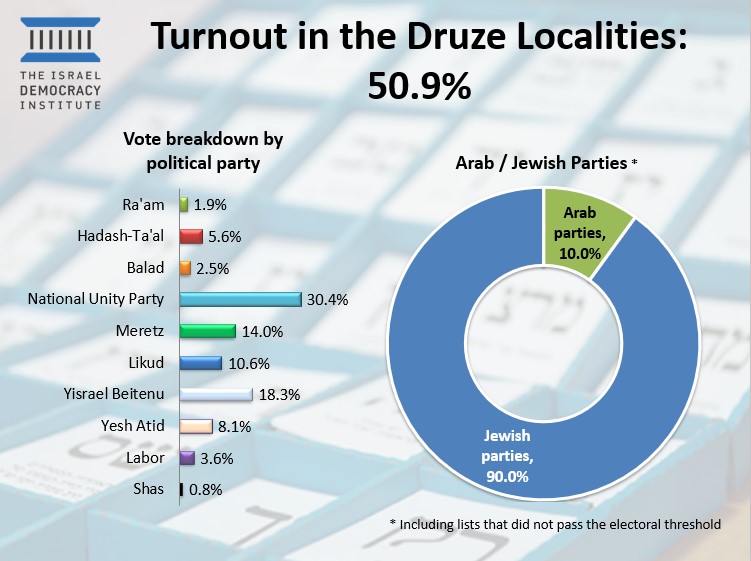

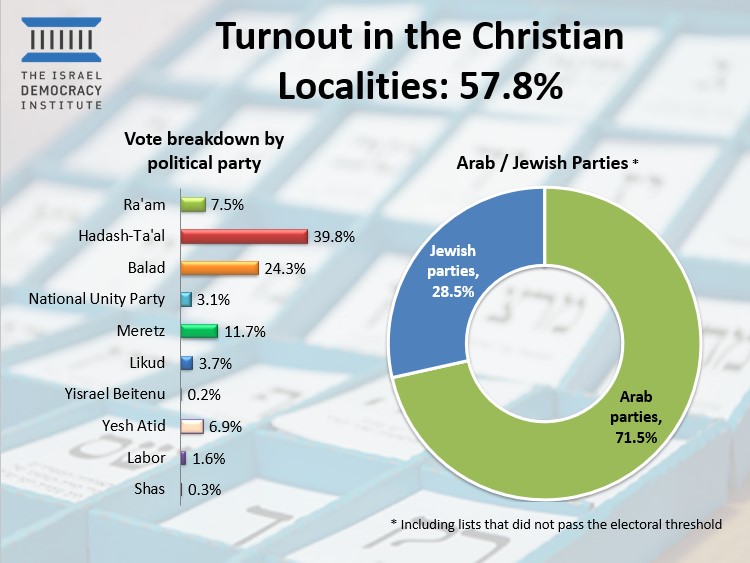

In Druze localities, the Zionist parties won almost all the votes (90%); the National Unity Party came out ahead (30.4%), followed by Yisrael Beitenu (18.3%), Meretz (14%), and the Likud (10.6%). In some Christian villages in Galilee, Hadash-Ta’al finished first (39.8%), followed by Balad (24.3%). Meretz (11.7%) outpolled Ra’am in these localities (7.5%).

The election results left Druze representation in the Knesset at an all-time low: there is now only one Druze Knesset member, Hamad Amar, who was number six on Yisrael Beitenu's list. All the other Jewish parties, including the Likud, the National Unity Party, Labor, and Meretz, included Druze candidates. These attracted many votes from their coreligionists, but failed to make it into the Knesset, since their slots were too far down. Ali Salalha, the only Druze placed in a realistic spot (number 4 for Meretz), did not return to the Knesset because Meretz failed to clear the electoral threshold.

This low point in Druze parliamentary representation, along with the fact that average turnout among the Druze in the last two elections (2021 and 2022, 48.7%) was significantly below their average in the five preceding elections (2013–2020, 55.9%), suggests that Druze society is dealing with a sense of its political marginalization and deepening crisis of orientation.

The Triangle

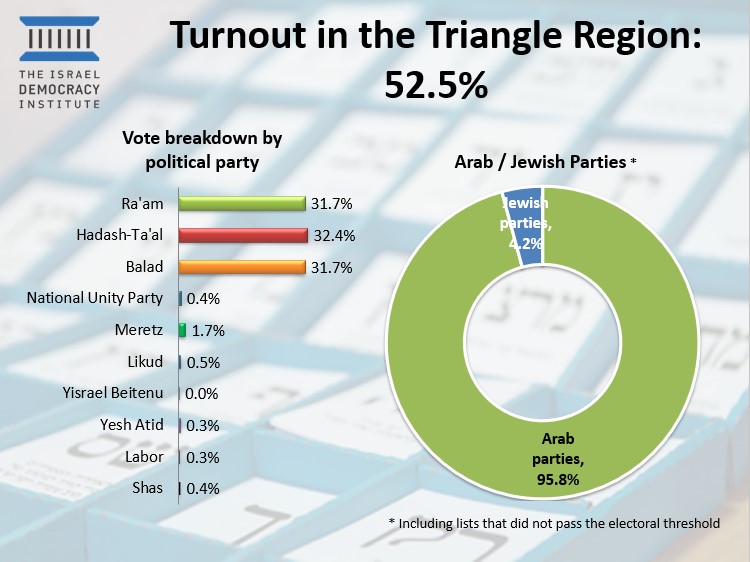

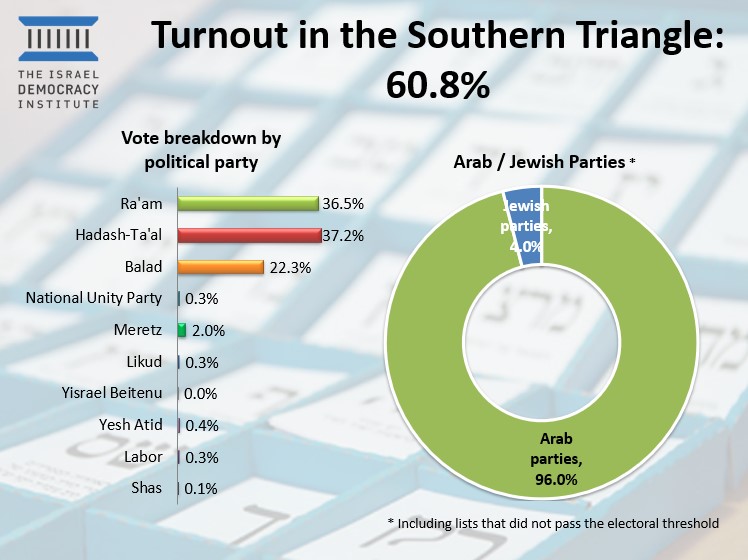

Turnout in the Triangle was 52.5%, close to the nationwide average for Arab and Druze localities. Overall in the Triangle, the three Arab lists finished almost in a tie. t: Ra’am, 31 7%; Hadash-Ta’al, 32.4%; and Balad, 31.7%. However, a comparison of turnout and voting patterns between the northern and southern Triangle reveals significant differences. In the southern Triangle, turnout (60.8%) was much higher than the national average. The strongest turnout in the Triangle was in the urban localities in its southern half: Jaljulya (69.5%), Kafr Qassem (66.9%), Kafr Bara (64.8%), and Tira (62.3%).

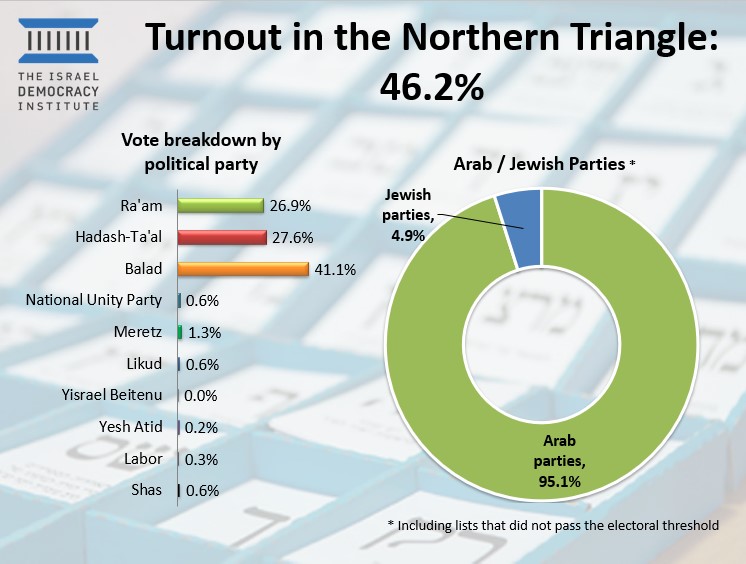

On the other hand, turnout in the northern Triangle was particularly low (46.2%). Only in Kafr Qara (62.2%) was there a high turnout. In Baqa al-Gharbiyeh, the home of the fourth candidate on the Balad list, Walid Qadan, turnout was low (47.5%). But the lowest turnout, only 38.3%, was in the city of Umm al-Fahm. Not only was this the lowest turnout in the entire Triangle, it was also the lowest in all Arab urban localities.

In the southern Triangle, the dominant parties were Hadash-Ta’al (37.2%) and Ra’am (36.5%); Balad dominated in the northern Triangle (41.1%). Voting patterns do not necessarily indicate that there are different political orientations in different parts of the Triangle, but reflect voters’ personal identification with a candidate who is their neighbor. In the southern Triangle this meant Walid Taha of Kafr Qassem (Ra’am) and Ahmed Tibi from Tayyibe (Hadash-Ta’al), who pulled in many voters; in the northern Triangle it was Walid Qadan of Baqa al-Gharbiyeh (Balad). These voting patterns are a clear example of the favorite son phenomenon in Arab politics, already mentioned above.

The Jerusalem Corridor

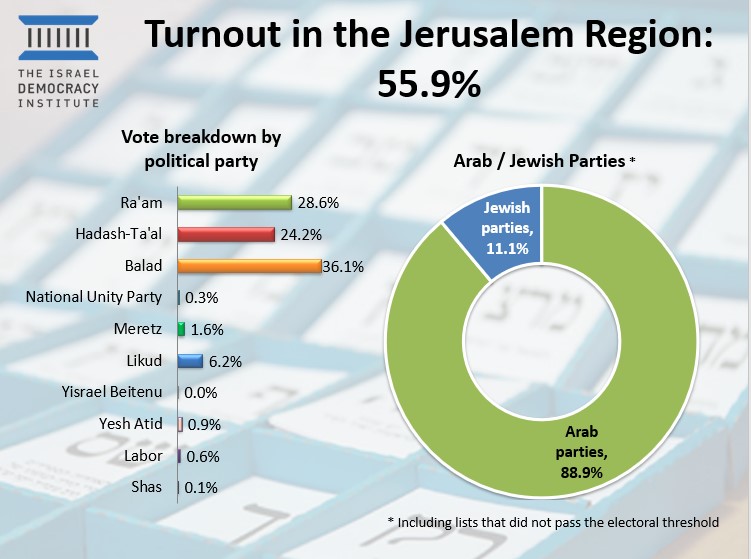

There are three Arab localities in the Jerusalem corridor region: Abu Ghosh, Ayn Naquba, and Ayn Rafa. Here, turnout was 55.9%, slightly above the national average for Arab and Druze localities. Balad (36.1%) enjoyed slightly more support than Ra’am (28.6%) and Hadash-Ta’al (24.2%). The Likud, too, enjoyed notable success (6.2%), far ahead of the other Jewish parties, which received only a negligible number of votes.

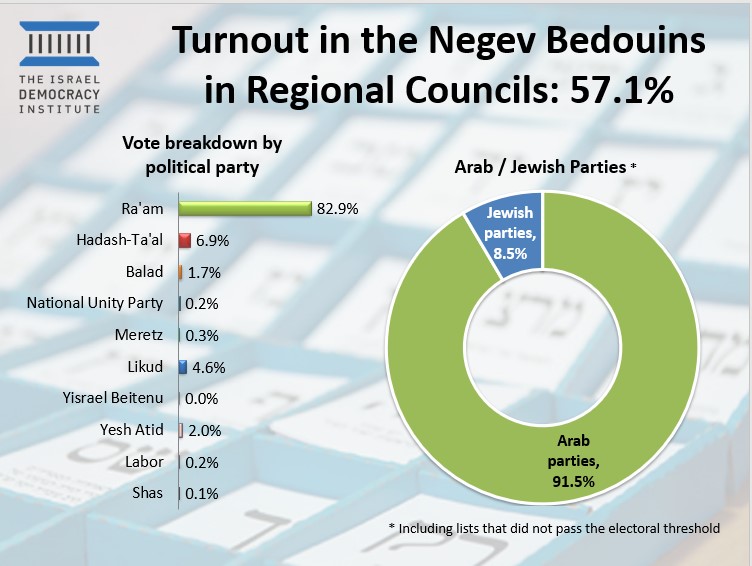

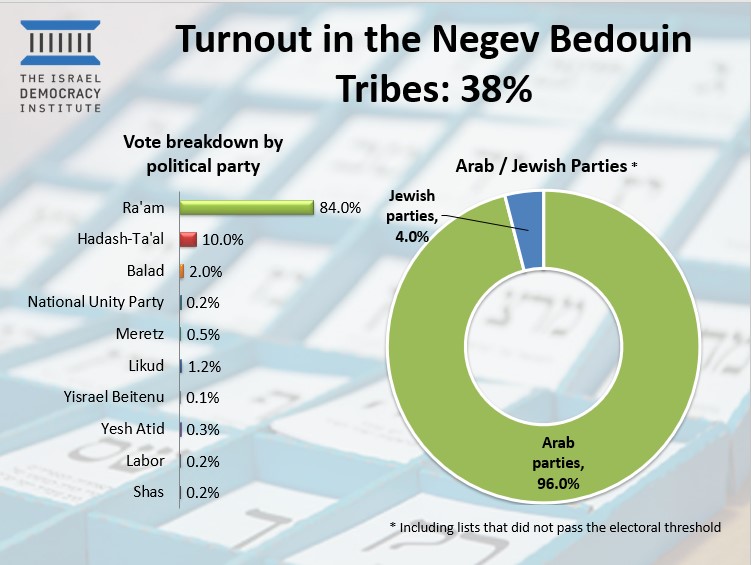

The Negev

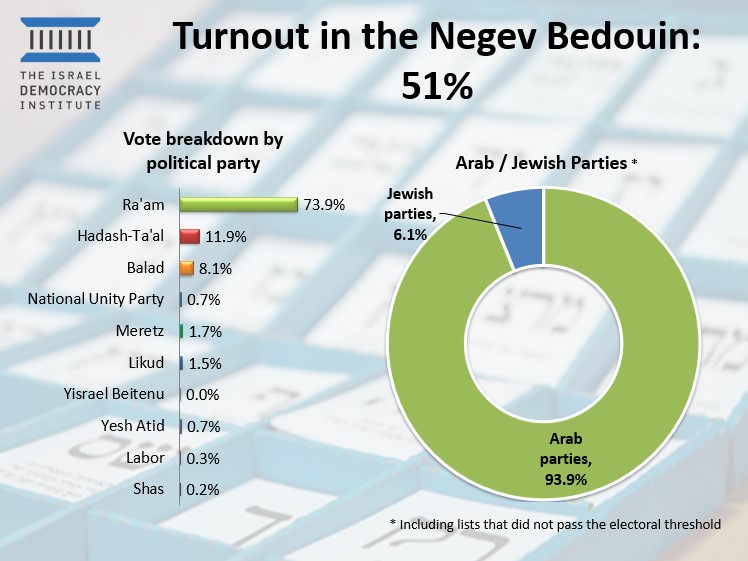

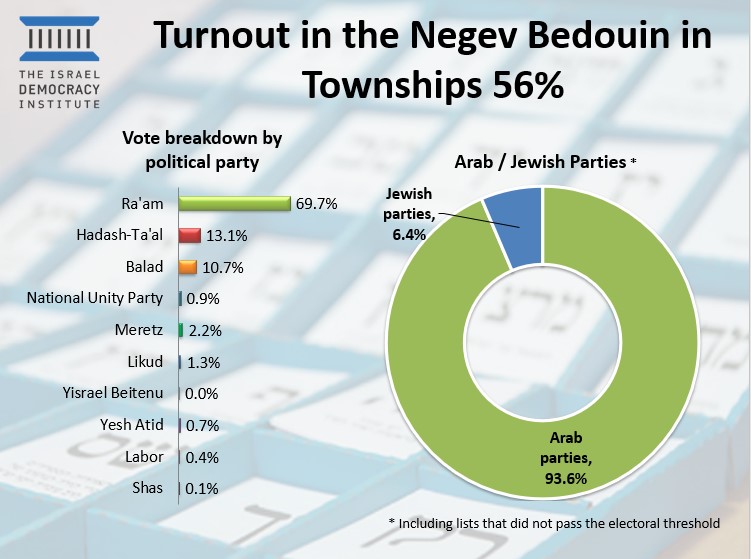

Voting patterns in the Negev demonstrate the extent to which the Islamic Movement has taken root in that part of the country. Ra’am reigns supreme (73.9%), significantly ahead of Hadash-Ta’al (11.9%) and Balad (8.1%). The fact that Ra’am places the challenges faced by the Negev Bedouin at the top of its priorities, and slotted a well-known figure, Walid al-Huashla, third on its list, explains the overwhelming support it enjoyed there. Al-Huashla is a member of the Islamic Movement and Ra’am's senior representative in the Negev—the successor to Sa’id Kharumi, also from the Negev, who died suddenly last summer.

Note that this is the second consecutive election in which support for Ra’am from Negev voters has been worth at least one Knesset seat. In 2021, Bedouin voters provided Ra’am with its fourth seat and enabled it to pass the threshold; this time Ra’am’s support in the Negev was even greater. The Hadash-Ta’al and Balad lists did not do well among Bedouin voters, even though Hadash-Ta’al placed a Negev resident, Yusuf Atawana (fifth on its list), in the Knesset.

Thus for the first time since the elections for the 20th Knesset in 2015, when the Joint List was originally formed, two representatives of the Negev were elected on Arab lists: Walid al-Huashla and Yusuf Atawana. To them, we can add Yasir Hujeirat of Ra’am, a member of a large Bedouin tribe in the north. The share of Bedouin representation in the Knesset (30% of the Arab MKs) corresponds to the growth in the weight and significance of Bedouin issues in Arab politics in recent years.

The electoral significance of the Negev is shown by the fact that the proportion of eligible Arab voters in the Negev among all eligible Arab voters in the country has been rising steadily in recent years. In 1992, for example, they accounted for only 8.6% of all eligible voters in Arab and Druze localities (excluding the mixed cities. A decade ago, in 2013, this figure had risen to 12.7%; in 2022 it reached 15.4%. We see that over three decades , the proportion of eligible Arab voters in the Negev has doubled.

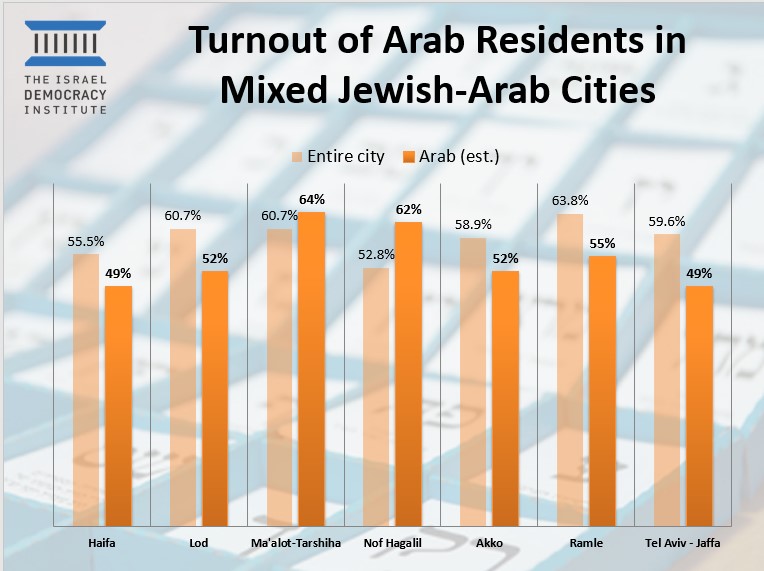

The Mixed Cities

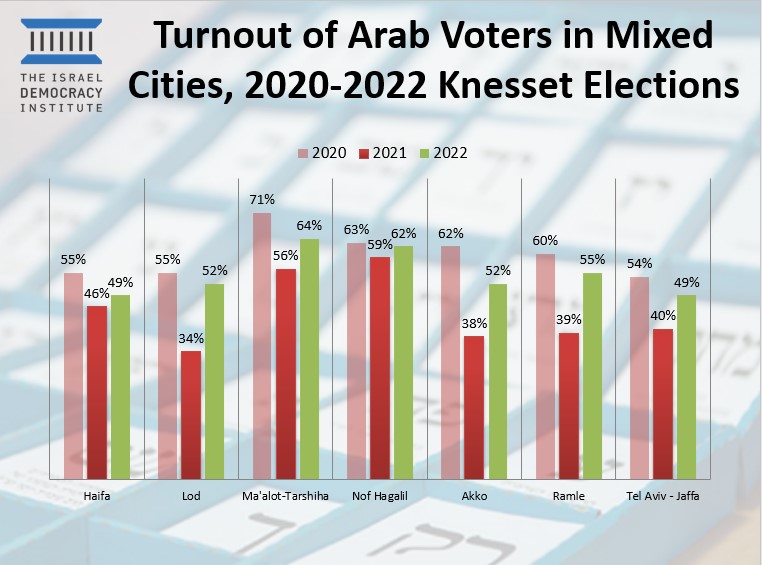

The fact that both Arabs and Jews live in the mixed cities makes it impossible to arrive at a precise measurement of turnout and voting patterns of Arab voters in these localities. For this reason, our estimate of Arab turnout in the mixed cities is based on a sample of polling stations in each of them, where the overall rate of support for Arab parties was particularly high, close to the average in Arab localities. From this we learn that Arab turnout in the mixed cities is generally lower than the urban average, except for two localities in the North—Ma’alot-Tarshicha and Nof Hagalil, where, according to our estimate, Arab turnout was higher than the average for urban localities.

A comparison of the estimated turnout of Arab voters in the last three Knesset elections, reveals an interesting trend. In some mixed cities, especially Lod and Nof Hagalil, Arab turnout the last time three Arab lists ran separately was significantly higher than it was in 2021, almost matching the high point of the 2020 elections, when all the Arab parties ran on the Joint List. It will be remembered that in 2020, the Joint List reached its peak with 15 Knesset seats, thanks to a significant increase in Arab turnout throughout the country. These findings corroborate the conclusion that healthy competition among the Arab parties contributes to a larger turnout by Arab voters (in Arab localities and the mixed cities.

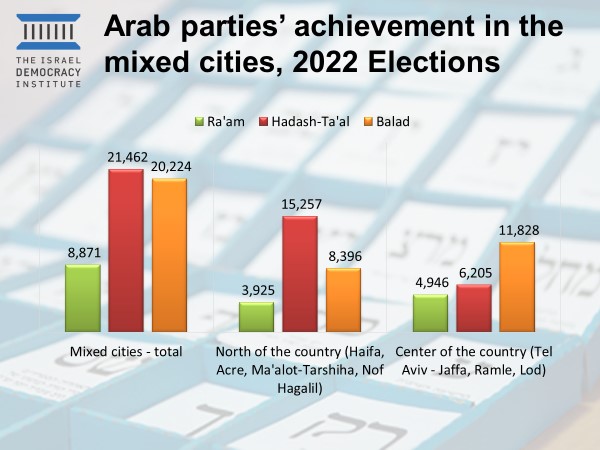

An analysis of voting for Arab lists in mixed cities reveals a significant difference in the patterns in the north (Haifa, Acre, Ma’alot-Tarshiha, Nof Hagalil) and those in central Israel (Tel Aviv-Yafo, Ramle, Lod). In the north, the dominant Arab list is Hadash-Ta’al, which outpolled the other two lists combined. This pattern is consistent with Hadash-Ta’al's dominance in the Arab localities in the north, which are the historical center of Hadash's support. By contrast, in the mixed cities in central Israel, the dominant Arab list is Balad, which outpolled the other two lists combined. This can be attributed to s the strong support for its Chair, Sami Abu Shehadeh, especially in Lod and Jaffa, where he is considered to be a hometown boy. If in the past, Hadash was dominant in the mixed cities (both in the north and center), the results of the last election suggest that Balad has caught up with Hadash-Ta’al in these cities.

Conclusion

Arab society can look back at the recent elections with mixed feelings. On the one hand, Arab citizens once again displayed interest in voting, and turnout was much higher than it was in the previous year. This made it possible for two Arab parties—Ra’am and Hadash-Ta’al—to maintain the 10 Knesset seats that all the Arab parties had held in the previous Knesset. On the other hand, Balad failed to clear the electoral threshold, meaning that for the first time since 1996, not all political streams in Arab society are represented in the Knesset.

Balad's fate in these elections is a classic example of the witticism that “the surgery was successful, but the patient died.” There is no doubt that Balad energized the atmosphere in the Arab street by running alone, and catalyzed the significant increase in Arab turnout. It is still too early to know whether the 2022 elections marked a turning point, such that the Arab parties again lead their public, but they may herald a renewal of the direct ties between the parties and the voters. From this perspective, these developments may be the very best news produced by the election.

Arab citizens attach great hopes to their elected representatives, regardless of the composition of the Knesset. On the reasonable assumption that there will not be new elections any time soon, the Arab parties- inside and outside the Knesset- have four years to gear up for the next campaign. They share the same goal: Forging stronger ties with their constituency. The preparations for the next elections are already underway.