The Ramifications of the Judicial Reform for the Status of Women in Israel

A professional opinion by the Israel Democracy Institute presented in advance of the session of the Knesset Committee on the Status of Women and Gender Equality on February 20, 2023

Background

The package of bills submitted to the Knesset by Justice Minister Yariv Levin and the Chair of the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee, MK Simcha Rotman, propose dramatic changes in the Israeli judicial system and the relations between the branches of government.

In the professional opinion below, we focus on how the proposed changes, will directly impact the nature of the regime in Israel and consequently have a profound and substantive effect on the defense of the rights of women from various sectors of the population, directly and immediately.

Each bill on its own and all of them taken together would undermine the protection of women's' rights from various sectors of the population, and mainly women from marginalized groups.

1. Democracy is an essential condition for full equal rights for women. Accordingly, indexes that examine the degree of democracy in various countries include the extent to which women enjoy political and social rights. For example, the criteria for Freedom House’s Democracy Index include whether women can vote, choose their own spouse, are protected against domestic violence, and morehttps://freedomhouse.org/country/israel/freedom-world/2022. Restrictions on women’s rights, such as their exclusion from the public space, can be another marker of the decline of democracy in a particular country.

2. Accordingly, the report of UN WOMEN examined the influence of the retreat of democracy in recent years in countries such as Poland, Hungary, and Croatia, and noted that the undermining of democratic institutions in those countries (such as the political echelon’s seizure of total control of the mechanism for selecting judges and neutralization of the court’s ability to conduct judicial review) harmed women’s rights. In Poland, for example, the assault on the independence of the judiciary was accompanied by various initiatives depriving women of autonomy over their own body, including the effective elimination of the right to abortion, alongside an assault on LGBTQ rights. According to the report, a similar process has taken place in Hungary, where, alongside the assault on democratic institutions, there has been an attack on women’s organizations, which were designated “foreign agents” that threaten the country’s national identity. Hungary’s commitment to the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention) has been interpreted as harmful to traditional family values and the institution of marriageConny Roggeband and Andrea Krizsán, Democratic Backsliding and the Backlash Against Women’s Rights: Understanding The Current Challenges for Feminist Politics, UN Women, June 2020.

3. The current situation in Israel is that women’s rights are not adequately protected. Women are not appropriately represented in the senior ranks of government ministries and local authorities (only 14 of the 257 local authorities are headed by women); many women are the victims of various forms of violence (the estimate is that approximately a million women and children Israel are exposed to domestic violence); women suffer significant wage differentials in the job market; and a large percentage of working women hold low-paying jobs, especially women from groups that are the victim of discrimination, such as the ultra-Orthodox and Arabs.

4. Accordingly, the possibility that in the future the Supreme Court and other protective mechanisms would no longer be able to provide a remedy for discrimination against women constitutes another acute blow to women’s rights and would leave them almost totally defenseless.

The impact on the court’s ability for effective constitutional review of laws

5. The values stated in the Declaration of Independence, which guarantees equal rights “irrespective of religion, race, or gender; laws passed in Israel over the years that are based on the principle of women’s equality (such as the Women’s Equal Rights Law and the Law on Employment of Women u; Government decisions; international conventions and resolutions that Israel has signed or incorporated into its law book (such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women [1979] and UN Security Council Resolution 1325 [2000])—these have afforded only a partial guarantee of equality for women. By virtue of their role, the courts in Israel have been the venue for protecting women’s rights in those cases when legislation was inadequate or not implemented, and on rare occasions even injured women.

6. The stipulation that the agreement of the full-or nearly full- bench would be required for the court to strike down discriminatory legislation that does not serve an appropriate purpose or is disproportionate, would directly and severely constrain the protection of women’s rights and the possibility of blocking legislative initiatives that are harmful to women.

7. For example, the Supreme Court sitting as the High Court of Justice, would no longer be able to intervene in a case such as that of a single mother with impaired hearing whom the law deprived of her disability allowance because she used a motor vehicle three times a month—leaving her and her two children with a total monthly income of only 1,841 shekels. In one of its very rare rulings (one of the only 22 times it struck down a law), the High Court ruled, that this section of the law was disproportionate and consequently should be annulled. Setting an almost impossible threshold for the court to strike down a discriminatory or disproportionate law would leave such women without constitutional protection.

8. The current Government’s coalition agreements include clauses that could deal a harsh blow to the constitutional right to equality, such as amendment of the antidiscrimination law to abolish the definition of gender segregation as unlawful discrimination. It follows that any harm done to the High Court’s ability to conduct constitutional review of these laws would prevent it from intervening in the cases of such legislation, and leave direct blows to women’s rights in effect.

The effect of limiting constitutional review to cases in which a law stands in substantive contradiction to a specific provision of a Basic Law

9. Limiting its power to intervene in cases in which a law contradicts an explicit provision of a Basic Law would make it difficult for the court to provide an expansive and appropriate interpretation of the principle of human dignity and grant constitutional protection to the right to equality and the prohibition of discrimination against women. This should be seen in light of the fact that although over the years, the court established equality as a right in its rulings, the constitutional entrenchment of human dignity had to wait for the enactment of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Freedom in 1992, which fortified the commitment to protection against discrimination, even though equality is not explicitly mentioned in that law.

Passage of an override clause with a majority of 61 Knesset members

10. Even after setting an almost impossible threshold for the court to strike down a law, the justice minister and the Chair of the Knesset Constitution committee propose to enact an override clause that would make it possible for the minimum coalition majority of 61 Knesset members to override a ruling by the court and stipulate that a law that infringes a fundamental constitutional right can take effect. This would leave the women of Israel defenseless against any majority that sought to limit their rights. It should be added that the proposed override clause could apply to all rights enjoyed by citizens of Israel—not only those stated explicitly in the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Freedom, but also those stated in the Basic Law: The Knesset (the right to vote and be elected), the principle of equal representation in voting, and more.

11. It follows that an override clause would do substantive damage to the defense of women’s rights and turn their already limited protection by the High Court into an empty shell. Note that the override clause enacted in Canada (one of the only two countries in the world with such a mechanism) rules out the passage of a law that violates equality between women and men. That is, when it passed the override clause, the Canadian legislature placed limits on it, and set any infringement of gender equality beyond the pale; but that restriction is not part of the override clause proposed today in Israel.

Limits on the court’s ability to engage in constitutional review of a Basic Law

12. The legislative proposals would deny the High Court the authority to conduct judicial review of Basic Laws. In this situation, the Knesset would be able to abuse its constitutional function and enact a Basic Law that discriminates against or is harmful to women, and the court would be powerless to intervene. Today there is no definition of a Basic Law, the topics covered by it, or the procedure for enacting it. Consequently, there are grounds for fearing abuse of this process as a way to make a discriminatory proposal unassailable. Already today, we see from the coalition agreements that one of the coalition’s goals is to enact a Basic Law to regulate government policy on immigration. Alongside the question of why this topic needs to be covered by a Basic Law, we may wonder how it will be possible to protect women if a substantive infringement of their fundamental rights is enshrined in a Basic Law.

A change in the composition of the Judicial Appointments Committee

13. The proposal to modify the composition of the Judicial Appointments Committee would guarantee only three female members out of nine, rather than four, as required by the Basic Law: The Judiciary. There is no doubt that even today women's representation on the Supreme Court is inadequate along with under-representation of women from diverse sectors of the population on the lower courts, especially women from sectors that are discriminated against, such as the Ultra-Orthodox, Arabs, Ethiopian Israelis, and Mizrahim. Expanding the coalition’s power on the Judicial Appointments Committee and reducing the influence of the professional echelons would deal a strong and lethal blow to the fundamentals of democracy, the separation of powers, and the independence of the judiciary. Clearly it would not lead to increased representation for women (or other disempowered groups). This is particularly the case when the coalition itself is woefully deficient in the representation of women from diverse sectors of the population, given that only nine of its 64 Knesset members are women, and the fact that-in keeping with their worldview- two of the coalition parties have no female representatives.

14. Given women’s under-representation in the coalition, it may be assumed that making political considerations for the selection of judges more important than professional considerations might lead to newly appointed judges who are not committed to the principles of equal opportunity, human dignity, and the abolition of all overt or covert discrimination against women.

Abolition of the grounds of reasonability

15. The ground of reasonability allows the court to weigh whether a decision by a governmental agency is reasonable and to intervene if it deems the decision to be extremely unreasonable. Here, one of the decisive considerations the court makes use of is whether an administrative decision is contaminated by illogic, discrimination, or an infringement of women’s right to equality. For example, the High Court ruled that an explicit provision requiring women to retire at an earlier age than men was unreasonable, and consequently- invalid.

16. Elimination of the court’s power of judicial review based the on the grounds of reasonability would further constrict its ability to annul government decisions that did not include the principle of equality as a relevant consideration or that would unreasonably infringe on equality. This would also deprive women of protection against arbitrary and abusive government decisions.

In sum, each of the bills would undermine the protection of women from a variety of population groups.

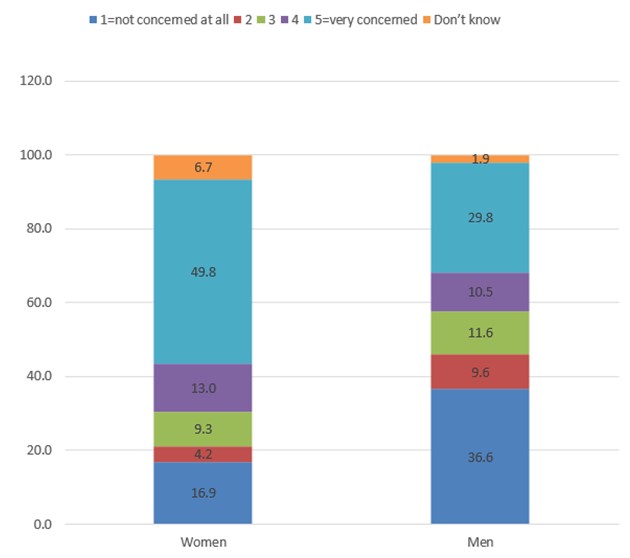

And so, there is good reason why women are troubled by the assault on gender equality, as shown by a survey conducted by the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research at the Israel Democracy Institute.

If the changes in the judicial system are approved, the coalition will be able to advance a number of proposals and curtail the court’s ability to engage in judicial review. On a scale of 1=not at all concerned to 5=greatly concerned, how troubled are you by the possibility of a retreat in gender equality?

It can be seen that 62.8% of women are "concerned or very concerned" by the possibility of a negative change in the area of gender equality (as opposed to only 40.3% of men). It should be emphasized that according to the survey findings, both women who voted for the coalition and those who voted for the opposition are concerned about the negative impact on gender equality.

This injury, especially in light of the already unequal status of women in Israel, is liable to take on critical significance and present an explicit threat to women’s rights, the principle of equality, a life with dignity, and protection of their bodies and freedom, and places protection of women in real danger.

Examples of High Court rulings that protected women's rights

HCJ 1512/04, Hanukkah versus the National Insurance Institute (published in Nevo, April 10, 2005). In response to the filing of the petition, the National Insurance Institute agreed to hold a hearing about its decision to cut off payment of an allowance because of the woman’s use of a motor vehicle or existence of an intimate relationship that made her ineligible to be recognized as a single parent.

HCJ 104/87, Dr. Nevo v. the National Labor Court, 44(4) 749 (1990). In 1990, the High Court of Justice ruled that different retirement ages for men and women must be eliminated. The campaign led to the passage of the Male and Female Workers (Equal Retirement Age) Law, which stipulates that if an earlier retirement age has been set for a woman than for a man, she is eligible to retire at any age between that set for women and that set for men.

HCJ 1758/11 Goren v. Home center Limited (Do It Yourself), Ltd., 65(3) 593 (2012). This was the first ruling by the High Court of Justice that dealt with wage discrimination. It held that employers may not discriminate on a gender basis when they provide benefits to their employees. The ruling was issued after earlier hearings in the Regional Labor Court and the National Labor Court.

HCJ 453/94, the Israel Women’s Network v. the Government of Israel, P.D. 48 (5) 501 (1994). This precedential ruling recognized the justified and imperative nature of affirmative action to deal with discrimination against women. It was only after the High Court intervened in the matter (1994) that the law mandating affirmative action for women was implemented. As a result, the percentage of women on company boards rose from negligible to about 30%.

HCJ 5660/10, Itakh–Lawyers for Justice v. the Prime Minister of Israel, P.D. 60 (1) 501 (2010). In 2010, Itach-Maaki filed suit against the Government of Israel in response to its failure to appoint any women to the Turkel Commission, the Government commission of inquiry into the Gaza flotilla. The High Court ruled that the absence of women on such an important body violated the Women’s Equal Rights Law and instructed the Government to add a woman to the commission.

HCJ 1823/15, Ben Porat v. the Parties Registrar (published in Nevo, January 10, 2019). The High Court instructed the Agudat Israel party to remove the word “man” from its bylaws so that there would no longer be any impediment, in its statutes or the law, to the acceptance of a woman as a party member.

HCJ 153/87, Shakdiel v. the Minister of Religious Affairs, P.D. 42 (2) 221 (1988). The court struck down the decision by a ministerial committee that ratified the composition of religious councils and refused to confirm Shakdiel’s appointment as a member of the Yeroham Religious Council. The High Court examined whether the ministerial committee’s grounds were objective (that is, such that a reasonable committee was entitled to take into account).

HCJ 8537/18, Jane Doe v. the Supreme Rabbinical Court in Jerusalem (published in Nevo, June 24, 2021). The High Court restored a woman’s right in an apartment on the basis of the assumption of joint property. It ruled that this right is not conditional and that “sexual infidelity is not a circumstance that can retroactively abolish rights once established.”

HCJ 7521/11, Azarya v. the Israel Police (published in Nevo, October 16, 2011). This ruling barred gender segregation on public streets. The justices held that a barrier to separate men and women could not be erected on the sidewalks of the Me’ah She’arim neighborhood in Jerusalem during the Simhat Beit Hasho’eva celebration. The court ordered the Jerusalem police to prevent such segregation and to ban the ushers from enforcing it.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Link to the full Hebrew opinion: https://www.idi.org.il/knesset-committees/48007