The Decline in Women’s Representation in Israel's Political System: Analysis

A Survey for International Women’s Day: 2023 Just one year ago, women’s representation in Israeli politics soared to an all-time high—in the Knesset, in the Government, and in local authorities. But today, we are going backwards. The approach of International Women’s Day is an appropriate time to look at the current situation and express concern as to this trend.

Photos by Flash 90

The issue of women’s representation in the political arena is currently at the heart of the public discourse in many countries around the world. The fundamental axiom at the basis of this discourse is the critical importance of a significant presence of women in political roles. Women’s inclusion in the public arena derives from democratic values such as equality and pluralism; such inclusion helps solidify their status in society and conveys the idea that women are equal citizens. The background of this discussion is the fact that in many countries the percentage of women among elected officials remains low. This gender disparity has led countries and parties to take steps to increase female representation in the political arena. A number of countries adopted quotas that have produced a consistent and major increase in the number of women in their legislatures. Recently there has also been an increase in the number of governments with gender parity—an equal number of men and women in ministerial positions.

Even though there are no statutory quotas in Israel, the country has seen a real improvement in women’s presence in politics, which registered an all-time high at the start of 2022. A year later, however, we are seeing a substantial decline.

Women in the Knesset

The most recent elections (November 2022) brought back 29 women to the Knesset. Changes since then have slightly increased the number: today, on the eve of International Women’s Day (March 8, 2023), there are 31 women in the Knesset—still less than 26% of the house. In a broad historical perspective, this is a major achievement, but it lags behind the figure of a year ago.

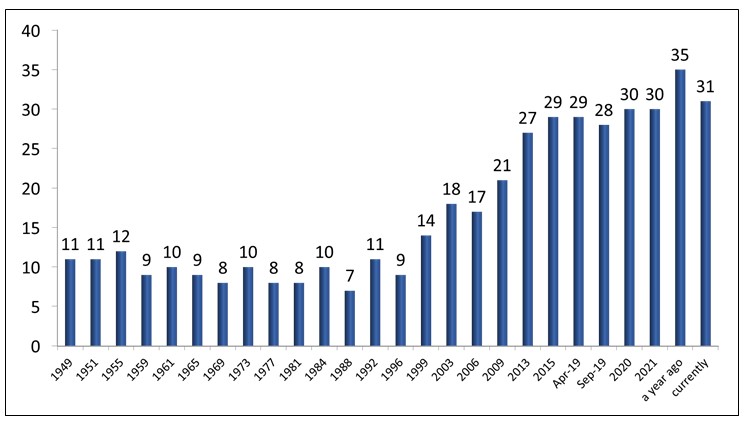

As can be seen in Figure 1, the first three Knesset elections produced a legislature with about 10% women. After that, over the course of four decades until 1999, the number of women in the Knesset was consistently lower, ranging from a low of seven (1988) to a high of 11 (1992). There was a sharp rise in the number of female Knesset members between 1996 and 2015, but since then there has been no significant change. In the last five elections, the number of women voted into the Knesset has ranged between 28 and 30. In the previous Knesset, extensive use of the Norwegian Law (a law enabling government ministers to resign from the Knesset and be replaced by another member of their party) brought the female contingent to 35.

Figure 1. Women in the Knesset: The number of Female MKs

* Except for the last two columns, the values show the number of female MKs at the beginning of each legislative term.

The rise in women's representation in the Israeli parliament is far from being a unique phenomenon. In fact, the surge in the number of women elected to parliament is one of the outstanding political phenomena of the last two decades, and not only in democracies. More tangibly, until 2003 there was only one country whose legislature included more than 40% women. Since then, more and more parliaments have crossed this line; the figure today is 29 countries. Israel now ranks 93rd among 192 countries with regard to female representation in its parliament. By comparison, a year ago it was in 61st place.

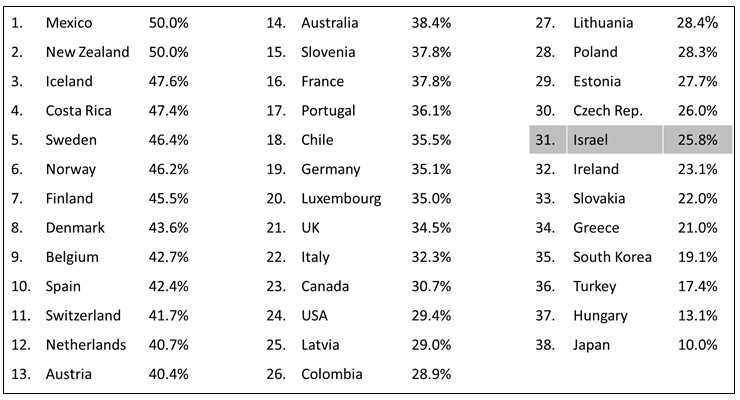

If we restrict the comparison to OECD countries, we find that Israel now ranks 31 out of 38 (Table 1). Here too there has been a sharp drop, since only a year ago Israel ranked 23rd.

Table 1. The Share of Women MPs in OECD Countries

Women in Government

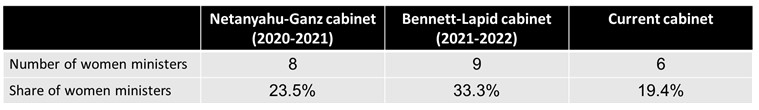

Until 1974, Golda Meir was the only woman to serve in an Israeli Government. She was followed by Shulamit Aloni (1974), Sarah Doron (1983), Shoshana Arbeli (1986), and Ora Namir (1992). Thus, only five women have held a ministerial portfolio from independence until 1996. Since then, another 27 women have been appointed to ministerial positions. Each of the two previous governments recorded a new high in female membership. The bloated 35th Government (the Netanyahu-Gantz Government) formed after the elections in 2020, began its term with a record number of eight women as ministers—double the previous high. Until then, no more than four women had ever served in the Government at the same time. The 36th Government (the Bennett-Lapid Government) broke this mark and included nine women, or one-third of the total ministers. The current Government represents a sharp retreat from these peaks. This is less obvious in absolute numbers but stands out in relative terms (Table 2).

Table 2. Women in the Last 3 Governments

When considering female representation in the Government, we should go beyond the dry numbers, since the increase in the female presence at the Government has not been translated into their appointment to the prestigious ministries. Only two women have ever served as Ministers of Foreign Affairs: Golda Meir (1956–1966) and Tzipi Livni (2006–2009). No woman has ever held the other two most prestigious portfolios—Defense and Finance. Over the last 14 years, not a single woman has served in any of the most senior political positions—Prime Minister, Defense Minister, Finance Minister, Foreign Minister.

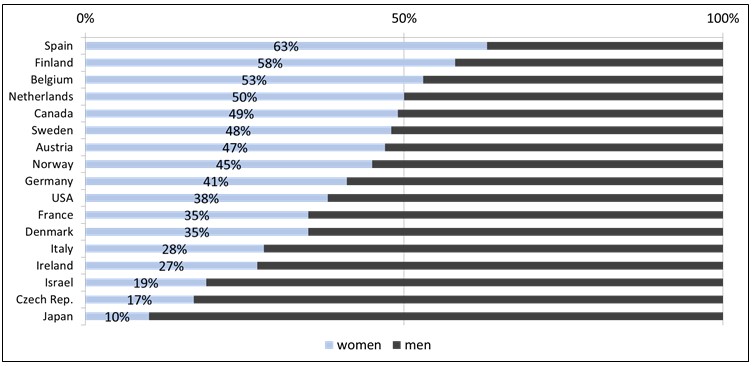

Furthermore, even if there has been a rise in the number of women in Israeli governments, the change has been slower than that in many democracies. In some, not only has the number of women increased, but there are also instances of gender parity or even a female majority in the government. As can be seen in Figure 2, the current governments of Spain, Finland and Belgium have a female majority; those in the Netherlands, Canada, and Sweden have an equal or almost equal number of men and women. A significant improvement has also been registered in the United States. Only three years ago, women constituted only 13% of Donald Trump’s cabinet. Today, under Joe Biden, the figure has zoomed to 38%, including the first woman vice president and the first woman to serve as Secretary of the Treasury (Janet Yellen).

Figure 2. Cabinet Ministers – by Gender

Women “at the Top”

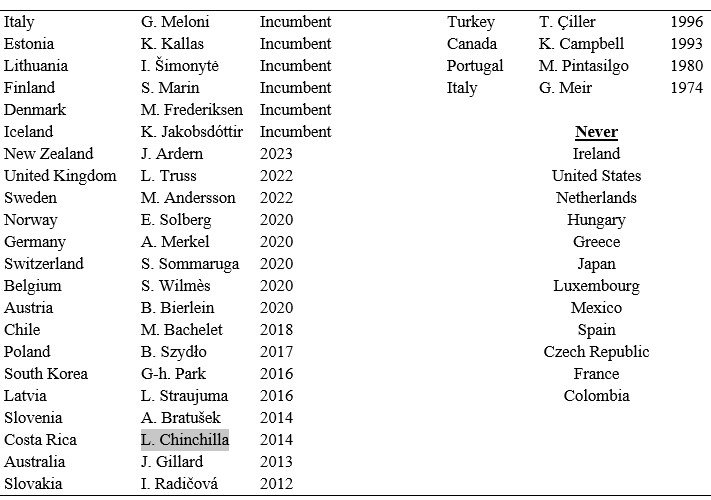

The number of women who have held their country’s most senior political position (prime minister or executive president) has increased significantly over the last two decades. Today, women hold the most senior position in six of the 38 OECD countries. These include Giorgia Meloni in Italy, Mette Frederiksen in Denmark, and Sanna Marin in Finland. As can be seen in Table 3, since 2012 more than half of the OECD countries (22 out of 38) have had a woman prime minister or president. This list includes countries where this was the first time that the glass ceiling had been broken (Italy, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Sweden), and others where women had previously reached the top (UK, New Zealand). In 12 of the 38 OECD countries, no woman has yet held the most senior position. These include the United States, but Kamala Harris’s ascension to the vice presidency, the first woman to do so, is an important milestone in this respect.

Table 3: Most recent year in which a woman held the highest political office* in the 38 OECD countries

*Prime minister or president in a presidential democracy (excluding ceremonial heads of state)

Israel was one of the first countries in which a woman held the most senior political position. When Golda Meir was named Prime Minister in 1969, she was only the third woman in the world to have reached that position. However, since her resignation in 1974, all ten Israeli prime ministers have been men.

Conclusion

After many years of an upward trend, women’s presence in the Israeli political arena is now in retreat, and the rise in their parliamentary representation has been halted. The peak reached in the Bennett-Lapid Government has been followed by a significant decrease in female membership in the current Government. In other respects as well, progress on this front has been suspended. For example, today only one party is headed by a woman—Merav Michaeli of Labor. A decade ago, three women served as party leader (Tzipi Livni of Hatnuah, Zehava Galon of Meretz, and Shelly Yacimovitch of Labor). And as long as the ultra-Orthodox parties persist in their refusal to include women on their slates, there is little chance of reaching gender parity in the Knesset. The road to fair and appropriate representation that reflects women’s share in the population remains long.

Nor should we forget that political representation is only one aspect of gender equality. Another important aspect relates to women’s economic status. Here the picture in Israel is even less encouraging: Alongside women’s high rate of participation in the labor force (23rd in the world, according to the Global Gender Gap Report 2022), there are very large wage disparities between Israeli women and men who hold similar positions (97th place) and an abysmal record in senior managerial positions (68th place).

Finally, it is impossible to ignore the elephant in the room: The current Government’s ideological bent does not herald good news for the status of women in society and for gender equality. Two examples of this are the commitment in coalition agreements that Israel will not join the Istanbul Convention (Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence) and the agreement (also in the coalition agreements) to permit and normalize gender segregation in the public arena. Looming above all this is the black flag of the judicial upheaval that the Government is pushing with brutal and incomprehensible speed. These measures are liable to work a substantive change in the system of government in Israel and, inter alia, to undermine the protection of women’s rights.