The Ultra-Orthodox Community on the Conservatism-Modernism Spectrum

Israel’s ultra-Orthodox sector is less homogeneous than most assume.

Illustration | Flash 90

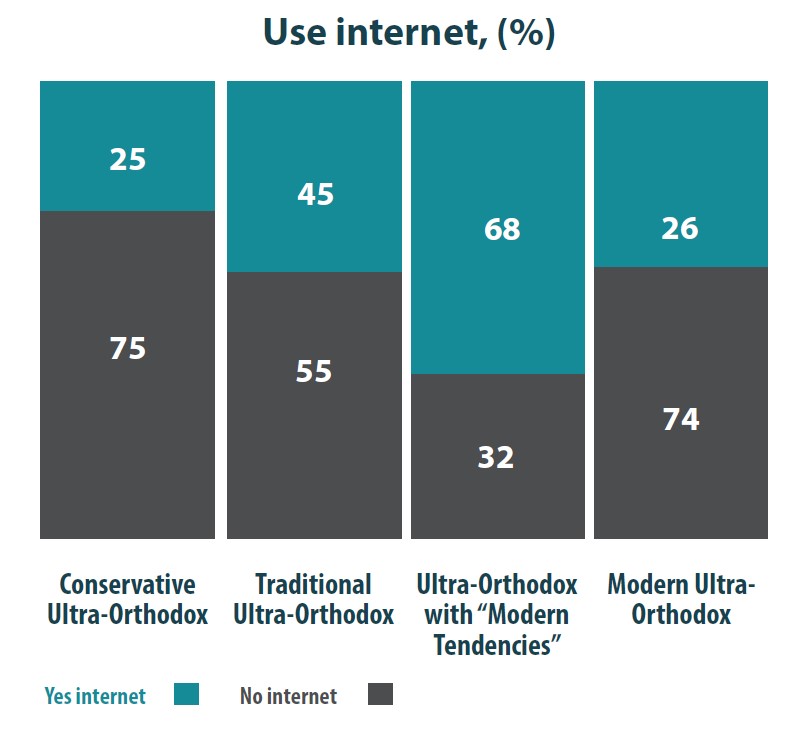

Israel’s ultra-Orthodox society numbers one million (12% of the general population) and is, by definition, an insular society. However, this community has undergone deep processes of change in the past few decades, including leadership, cultural and economic shifts. These processes have expanded the borders of the “Ultra-Orthodox Core,” leading to the emergence of new groups and identities in this community, located on the entire spectrum from conservatism to modernity. (The ultra-Orthodox are often referred to as haredi – “trembling” in their service of God)

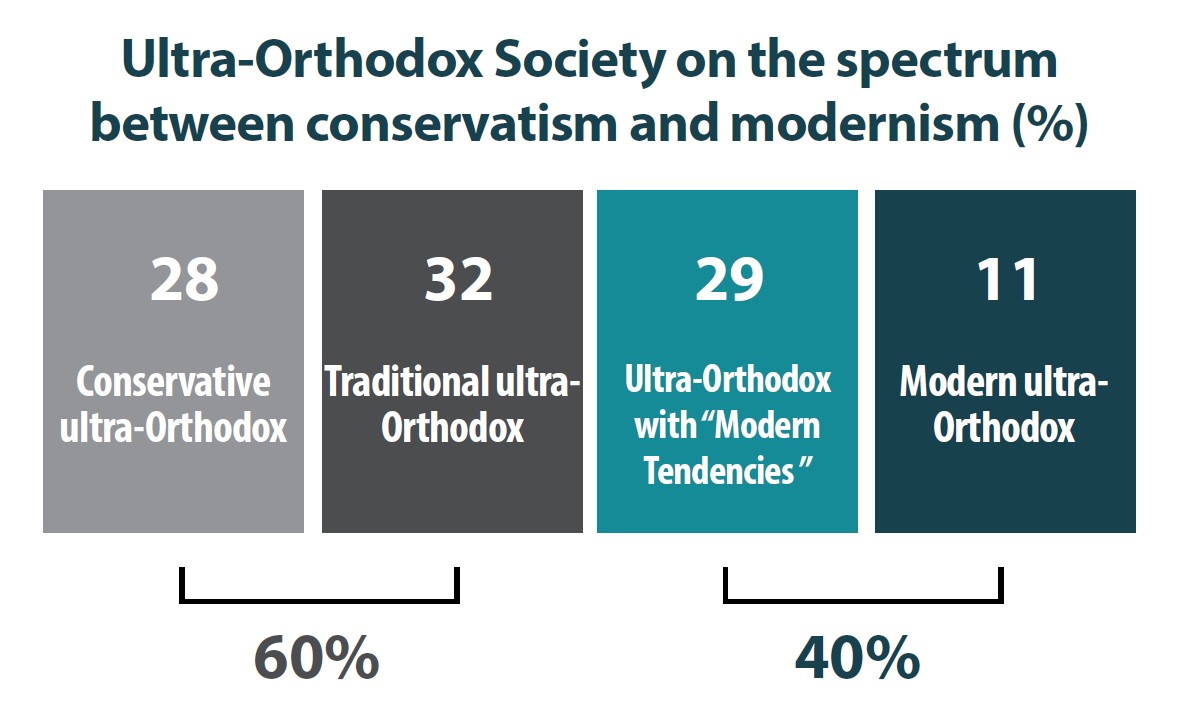

The Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) has conducted a new study suggesting that ultra-Orthodox society in Israel be classified, on a conservatism-modernism spectrum, into four main groups: conservative (28%), the classic core group (32%), a group leaning towards modernism (29%) and the modern group (11%). These sub-divisions exist in parallel to the main divisions on the axes of ethnicity and social status. These groups vary in their attitudes on various issues such as: demography, higher education, employment, lifestyle, media, attitudes towards the State of Israel, society and economics.

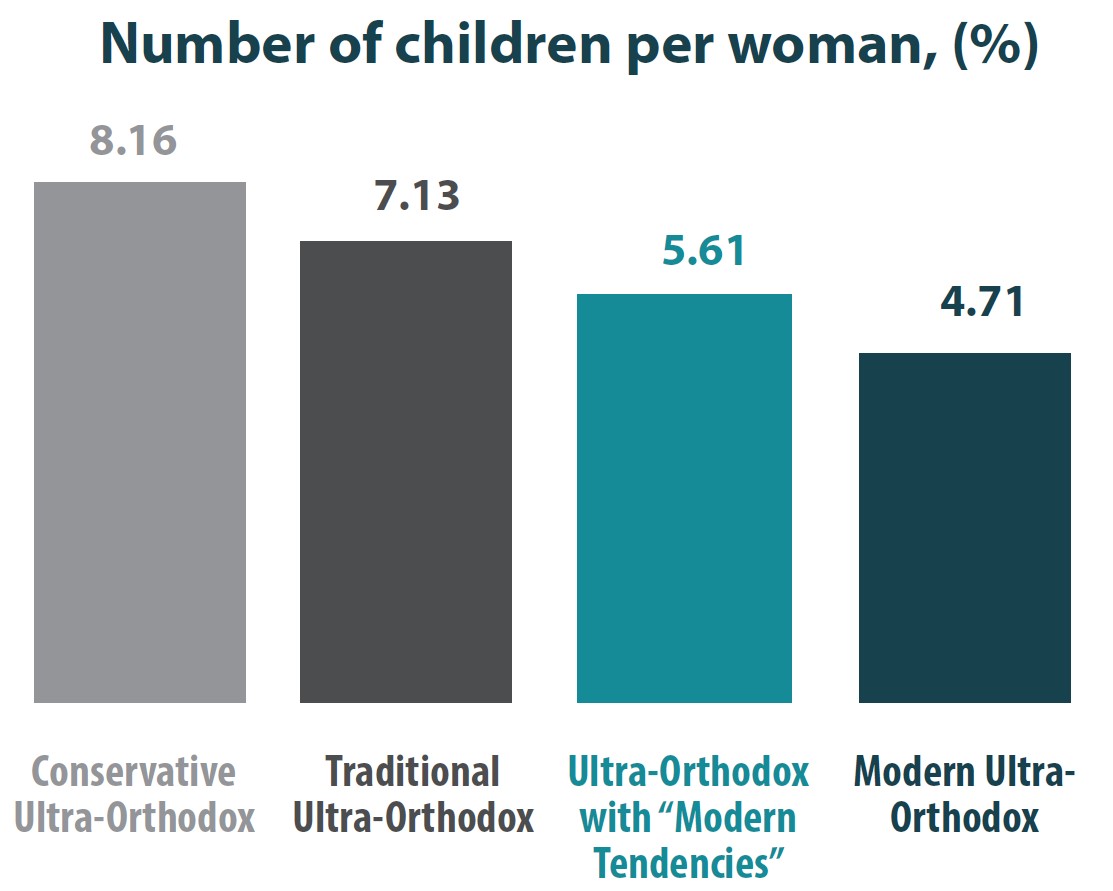

While negligible differences were found among the groups regarding average age of marriage, significant differences were found with regard to fertility rates: women belonging to the conservative group had on average eight children, whereas the modern women had four.

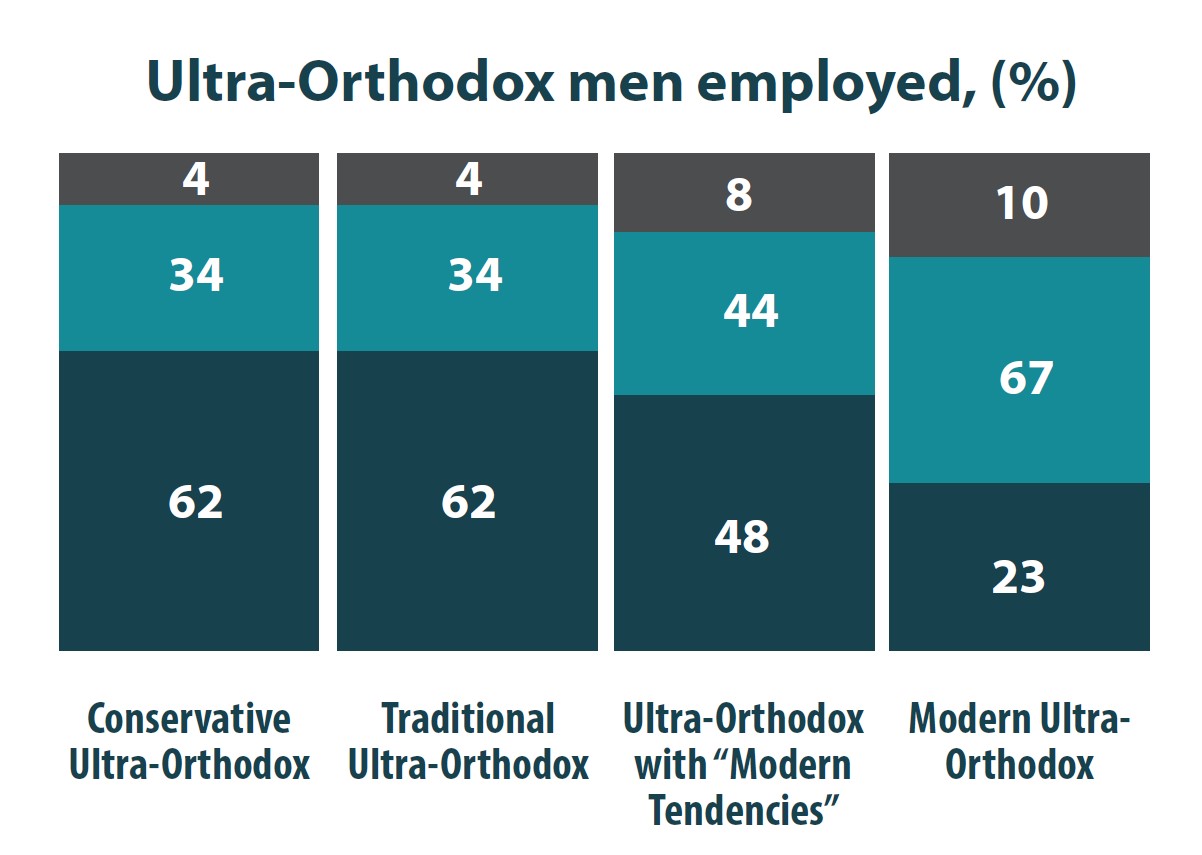

An examination of socio-economic status among the conservatives revealed that 67% of modern ultra-Orthodox men are employed, as opposed to just 34% among the conservative groups. Half of those in the first group work in a mixed, secular/ultra-Orthodox environment, as opposed to just 24% in the second group. 59% of the modern ultra-Orthodox do not oppose academic studies, and would send their children to an academic institution, as opposed to 21% of the conservatives. 63% are prepared to live in mixed neighborhoods (secular and others) and in cities adjacent to ultra-Orthodox areas, as opposed to just 11% of the conservative group.

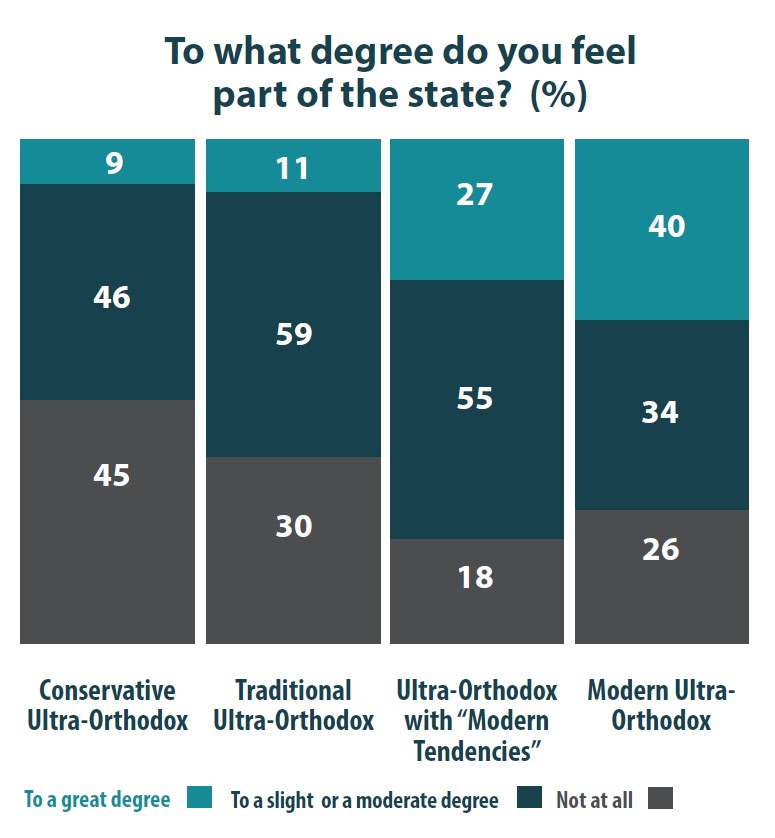

With regard to attitudes towards the State of Israel, it is important to note that almost half of the modern ultra-Orthodox identify with the State and support integration into broader society regarding employment and education, as opposed to less than 10% of the conservative ultra-Orthodox.

However, despite this finding, even among the modern groups, there is still significant opposition to male students studying core secular subjects in school and enlisting in the IDF.

The ultra-Orthodox are no longer a small, marginal group. Israel’s challenge is first to work with the two groups (the modern and those leaning to modernity), who comprise 40% of the ultra-Orthodox population, and to offer hundreds of thousands the opportunity for integration into general society.

This includes setting up the infrastructure for those who wish to live in non-ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods, establishing and supporting educational institutions that combine religious and secular studies, and strengthening special study programs that will open up opportunities for academic studies and employment. In addition, efforts must be made to better acquaint general Israeli society with this new range of identities in the ultra-Orthodox sector.

A deeper understanding of trends toward change in the community will help those among the ultra-Orthodox who wish to do so, to fully integrate into Israeli society in a respectful, meaningful way – and in a way that will grant them both equal rights and equal obligations.

The article appeared in the Jerusalem Post.