Where Have the Parties Gone?

Political parties no longer fulfill the goals for which they were intended, rather they have become technical structures that are focused on the ranking of the candidates on their Knesset lists.

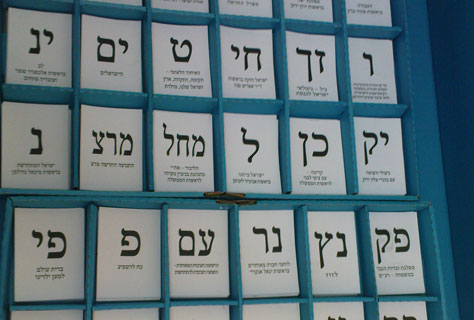

Just recently, Israel's political parties presented their slate of candidates for the March elections. But do these political structures still matter? The Israel Democracy Institute recently released its annual Israeli Democracy Index, which President Reuven Rivlin likens to an annual checkup on the health of Israeli democracy. This year's Index found that the public has less trust in political parties than in the rest of the country's public institutions. Only 14% of Jewish Israelis and 20% of Arab Israelis say that they trust political parties.

It should be noted that this low rate of approval is part of a long-standing trend. Since the first Democracy Index was published in 2003, political parties have always ranked at the very bottom of the trust scale of Israeli voters. How is it possible that the parties, which are the only institution elected directly by the public, inspire the least trust? And how can it be that the Knesset, which is made up of representatives of the parties and itself ranks very low on the public trust scale, nevertheless has achieved a score twice that of the parties?

One possible answer is that political parties today no longer fulfill the goals for which they were intended. They do not develop and refine an ideological agenda. Nor do they really cultivate new leadership and serve as a structure to choose and present candidates for the voters’ approval. In practice, they have become technical structures that, in the best case, are focused only on the ranking of the candidates on their Knesset lists.

It may be hard to believe today, but once upon a time Israel was a country where the party was paramount. The parties had active local branches and many registered members. One's party affiliation was important in almost every context of life: which HMO you belonged to, which youth group your children joined, whether you rooted for left-affiliated Hapoel or the right-leaning Maccabi sports teams, and whether you banked with Poalim or with Leumi. Party association was the key to almost everything else as well. This is not to say that this was an ideal reality. This party-centric outlook resulted in a country where people were regularly discriminated against for belong to the wrong party, or, as was often the case, the parties of the right.

The reinvention in recent years of parties as entities with no roots, with no local branches, with few members or weak institutions, but only a star-studded Knesset list, has damaged the image of what is still called a 'political party.' The party no longer has any meaning as an institution to which loyalty and investment over time can pay off—an institution in which there is continuity and real chances of advancement. It has become almost impossible to rise through the ranks, because the list is either completely dictated by those at the top or highly controlled by them. Candidates flit in and out of the partisan structure on the basis of name recognition.

The rapid turnover and contracting lifespan of many parties is another factor that dilutes public trust in them. I have personal experience with this phenomenon having served as the director general and subsequently as a Knesset member for Kadima, the only political party besides Labor or Likud to form a governing coalition since Israel's inception, only to disintegrate after only three terms. We also see that parties built around a single personality or a single idea, such as Moshe Kahlon’s Kulanu, do not have a long life expectancy and are doomed to vanish or be absorbed by other parties.

On the other hand, the niche and sectoral parties which have an identity-based constituency, like the Ultra-Orthodox, maintain their strength. As the Democracy Index shows, Shas and United Torah Judaism voters believe that the parties faithfully represent their positions: 74% of the Ultra-Orthodox reported that there is a party that speaks for them. This stands in stark contrast to 59% in the rest of the Jewish sector who feel this way.

Changes in the regulatory environment and reforms to our electoral system could strongly affect how we govern political parties and what their institutional makeup will look like. One possibility is to institute a semi-open ballot on Election Day in which voters will not only choose a party, but also which candidates from that slate should represent them in the Knesset. This would create a real connection between voters and the party leaders who represent them thereby strengthening their ideological structures. Another possible reform would be for the government to earmark a portion of the state financing, which is already allocated to political parties, limit the amount that can be spent on campaign expenses, and instead designate these funds for substantive rejuvenation of the parties through debate on policy formulation and ideology.

Whatever their faults and weaknesses, parties remain the fundamental building blocks of the parliamentary system. Israelis vote for parties to lead the country, and not directly for candidates. Political parties, which bring diverse interests together and channel the conflicts into the political arena, play an especially critical role in a deeply divided society such as Israel’s. We are facing a great and important challenge and the structure of the parties must be modified to suit the new era. Succeeding could allow public trust to be restored and, perhaps, ensure that when we present next year's Democracy Index to the President we will be able to say that political parties once again fulfill their vital roles in our democracy.

The article was published in the Times of Israel.