Is Israel Also Experiencing a “Great Resignation”?

The "great resignation" that has swept the US and UK in recent months is one of the symbols of the recovery from the pandemic. Is this trend taking place in Israel too?

Over recent months, public debate on the economic aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused on the number of people resigning from work, given the sharp rise in resignations in the United States and a similar trend in Britain. This development has become known as the Great Resignation, and in Israel (as elsewhere), is the context for discussions on economic recovery from the pandemic and the difficulties of filling jobs as the market reopens. Experts in Israel and abroad have offered different explanations for this phenomenon, including the possibility that workers’ preferences have changed following extended furlough periods, and that they are no longer interested in employment that is not sufficiently rewarding (in terms of satisfaction, a sense of self-actualization, and not only compensation) and does not provide a good enough life-work balance, such as sufficient leisure time or flexible working hours. Employers have reported that they are receiving far more demands for part-time work or working from home, and employers in the restaurant sector, industry, construction, and nursing have reported particular difficulties in finding workers.See, for example, Gamas Netanel, “Being brave: Resigning from work is no longer a privilege of people with money,” The Marker, August 29, 2021 [Hebrew], https://www.themarker.com/career/.premium-1.10160422; Avraham Tzlil, “Hayot Kis Episode 218: Where have the workers gone?”, Kan Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation, December 7, 2021 [Hebrew], https://www.kan.org.il/Podcast/item.aspx/?pid=25290.

We should note that this is not a worldwide phenomenon: The number of resignations has risen in the United States and Britain, but a similar increase has not been seen in other countries. At the time of this writing, data from Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and the European Union do not indicate a significant increase in resignations.The Economist, “Evidence for the ‘great resignation’ is thin on the ground,” December 11, 2021, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/evidence-for-the-great-resignation-is-thin-on-the-ground/21806659.

In this context, we sought to examine whether Israel is also experiencing a Great Resignation.

In this document, we use the term “resignees” to refer to individuals who have stopped working for personal reasons.The Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) records the reason for ending work only for those who were employed during the last two years and stopped working, and thus this data does not include those who resigned more than two years ago. The reasons we defined for resignation, as used by the CBS in its Labor Force Survey, include: “work did not suit their talents”; “were not satisfied with employment conditions: pay, work hours, location, etc.”; “health reasons”; “studies”; “to take care of the household or a family member”; “lived abroad”; and “other reason.” The reasons we did not include as resignation were retirement, being fired, concluding service in the IDF, or concluding an employment contract. All the data presented refer to the main working ages in Israel, 25–64. This definition includes both those currently seeking work and those who are not, a distinction we examine further below.

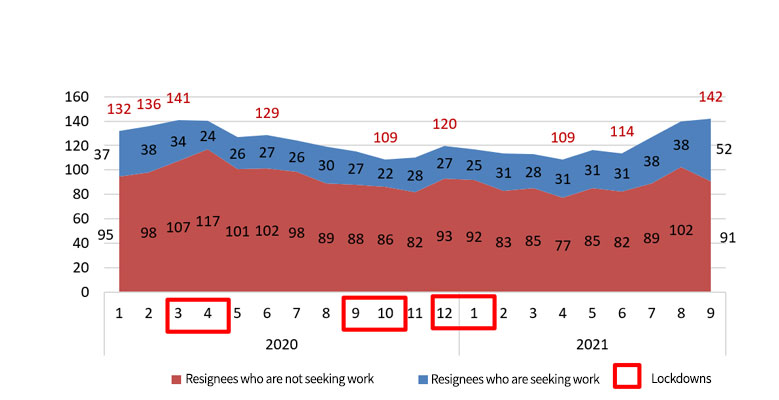

An analysis of Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) data carried out by researchers at the Israel Democracy Institute reveals that since May 2021, there has been a rise in the number and percentage of resignees (see Figure 1 below). The number of resignees (that is, the total number of workers who have resigned based on the CBS Labor Force Survey) increased from 109,000 in April 2021 to 142,000 in September 2021—the highest number in the last two years. A similar increase was also seen in the percentage of resignees relative to the number of individuals who were employed immediately before the pandemic (January–February 2020).

In fact, the total number of resignees as of September 2021 (142,000) and their share relative to those employed (4.9%) reached the highest levels recorded since the pandemic began. The figures are also high compared to the parallel figures from January–February 2020, when, according to CBS data, there were 134,000 resignees – that is 4.6% of those employed at the time.

The September 2021 figures on resignees reflect a rise of around 30% relative to April 2021 (an increase of 33,000 over five months), and a rise of 8% relative to the situation at the beginning of the pandemic (an increase of around 8,000 since January–February 2020).

Interestingly, the number and percentage of resignees rose sharply at the beginning of the pandemic (March and April 2020), with the initial shock to the system and what was the first and most stringent lockdown. This increase seems to stem from a desire to take advantage of the opportunity for eligibility for unemployment benefits, which were available to anyone who chose to resign due to being furloughed. It appears that this encouraged workers who had been considering resigning before the eruption of the crisis to do so now (resignees in Israel are usually entitled for unemployment benefits only 90 days after their resignation).See Kol Zchut website, “FAQ on the end of the coronavirus furlough scheme” [Hebrew]: “Furlough constitutes a substantial worsening of employment conditions. A worker who resigns due to being furloughed is entitled to the full range of compensation that would be due if they were fired.” https://www.kolzchut.org.il/he/שאלות_ותשובות_בנוגע_לסיום_התקופה_של_חופשה_ללא_תשלום_עקב_משבר_הקורונה# We believe that this is also the reason for the temporary rise, which was then quickly replaced by a downward trend in May 2020, when for a moment-- it seemed as if Israel might have defeated the virus. From May 2020 on, there was a drop in the number and percentage of workers who had resigned, even as the pandemic continued, as could be expected during a period of economic crisis and rising unemployment. As noted earlier, this downward trend was reversed in May 2021, with the onset of the current wave of resignations over the last six months or so.

This recent increase in the number and percentage of resignees has coincided with the lifting of many of the restrictions imposed during the third wave of the pandemicTaub Center website, “Israel Corona Timeline,” entry from November 27, 2021, .https://www.taubcenter.org.il/en/coronavirus-timeline/., and the termination of furlough payments at the end of June 2021. Such an increase is characteristic of a period of economic recovery, when workers feel more confident to leave their place of work, as the demand for employees increases. At the time of this writing, recently published data indicates that the demand for workers reached a new high of 143,000 available positions in October 2021.

Figure 1. Resignees in Israel 2020–2021, by those seeking work and those not seeking work, in thousands (total number shown in red)

Employers difficulties in recruiting workers for a wide range of available jobs—most of them jobs that pay around the minimum wage— reinforces the belief that the reason for the current growth in the number of resignations is linked to the fact that some workers have simply had enough of work, or at least of work that does not meet their expectations in terms of salary or professional satisfaction.

However, since the data covers a period of just five months, following a downward trend throughout the previous year, we believe that it is still too early to conclude that Israel is also experiencing a Great Resignation. We must wait for additional data in order to determine whether this is a temporary increase, reflecting a natural response to a period of economic recovery after a year in which people restrained their desire to resign and waited for stable recovery of the labor market, or whether it represents a change in workers’ preferences in the post-COVID era.

It should be noted that the data presented in this document on resignees includes both those who have remained in the workforce (that is, who have resigned but have continued to actively seek work) and resignees who are not seeking employment.

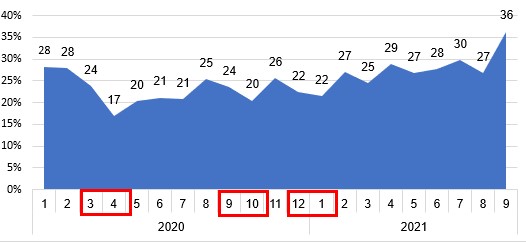

The percentage of resignees seeking work (that is, remained in the workforce) dropped during the first two months of the pandemic (March–April 2020), but since then has climbed gradually (with dips during each lockdown). This trend indicates resignees' desire to improve their situation in the labor market (by resigning and seeking alternative employment), and does not align with the theory that resignees are tired of employment in general and do not want to work at all. In fact, the percentage of resignees who are seeking work stood at 36% of all resignees in September 2021 (the most recently available figure at the time of this writing), 8 percentage points higher than the parallel figure in January–February 2020.

Figure 2. Resignees seeking work among all resignees (in %)

This is a positive trend, in that as the percentage of jobseekers among resignees grows, so will the likelihood that they will return to employment in the coming months. Indeed, CBS data for the first half of November 2021 revealed a sharp increase of almost 150,000 in the number of employed IsraelisRelative to the second half of October 2021., of which some 30,000 were individuals who had returned to work after being unemployed, and around 120,000 who were not in the workforce because they were not seeking work and who returned to the labor market as employees at the beginning of November 2021.Central Bureau of Statistics, “Data from the Labor Force Survey for the first half of November 2021,” December 6, 2021 [Hebrew], https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/pages/2021/נתונים-מסקר-כוח-אדם-למחצית-הראשונה-של-חודש-נובמבר-2021.aspx.

In conclusion, we believe that it is too early to conclude that Israel is indeed experiencing its own Great Resignation.

In this context, it is interesting to note that a considerable share of the “COVID unemployed” (salaried employees who were laid off, furloughed, or who resigned due to the pandemic) did not return to the same workplace or job when they went back to work. A survey of the labor market conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute in August 2021This was the fifth survey in the Israel Democracy Institute’s survey series “Israel’s labor market during the COVID-19 pandemic.” found that almost half the respondents who had been laid off or furloughed and returned to work, had changed their employer or their job. As shown in Figure 3 below, 24% had changed both their workplace and their job, and around 18% had changed their workplace but were in a similar job (making a total of 42% who had moved to a new employer), while some 5% had returned to the same workplace but were in a different job.Daphna Aviram-Nitzan and Yarden Keidar, “Why are the COVID unemployed not re-entering the labor market?”, November 15, 2021 [Hebrew], https://www.idi.org.il/articles/36626.

Figure 3. "COVID-19 Unemployed " who have returned to work, as of the end of August 2021, by workplace and job (%)

These findings reflect the dynamic nature of Israel’s labor market during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Israeli furlough model permitted a relatively easy transition between different workplaces. Unlike the German (European) model, furlough payments in Israel were transferred directly from the state to workers and not via employers, thus reducing workers’ dependence on their employer. These data may indicate that the European furlough model, which maintains a strong link between employer and employee in the course of a furlough, is more appropriate for short crises, while the Israeli model is better suited to prolonged crises such as the pandemic, in which the advantage of encouraging workers to find alternative employment with other employers outweighs the advantage of maintaining the employer-employee relationship. Of course, to arrive at such a conclusion a rigorous comparative examination of European states must be conducted. In addition, it is only fair to note that this analysis has the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, while when the furlough models were formulated and introduced, the policymakers had no idea how long the crisis would last.