The Burden of Reserve Duty on the Working Population in Israel

This study looks at the burden of IDF reserve duty on the working population in Israel, based on the most up-to-date data from the CBS Labor Force Survey.

Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90

This study looks at the burden of IDF reserve duty on the working population in Israel, based on the most up-to-date data from the CBS Labor Force Survey, made available for the purposes of this study.[1]

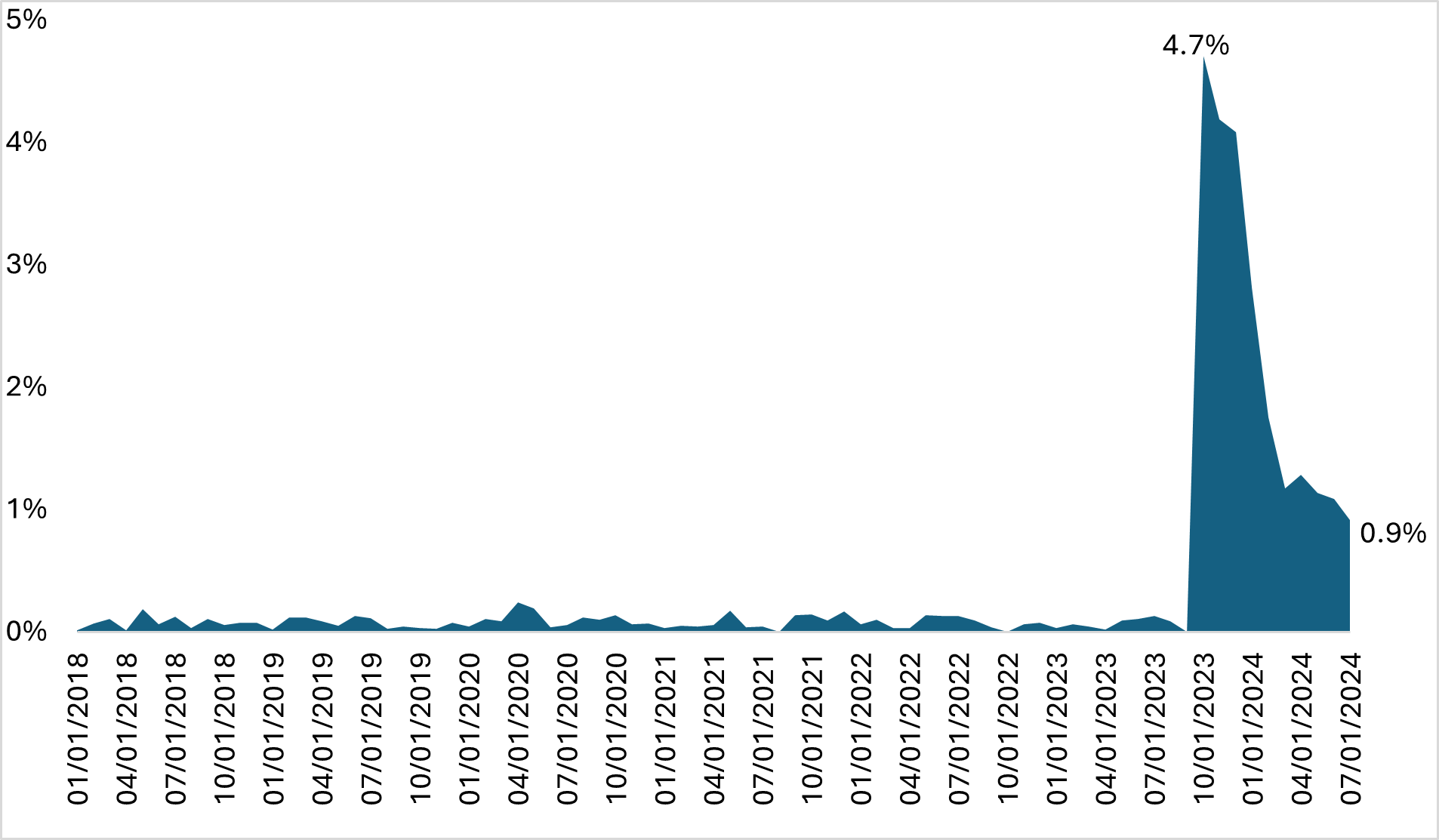

Prior to October 7, 2023, the burden of reserve duty on the working population was extremely low: from 2018 to 2023 (up to October), less than 0.1% of working hours were lost due to reserve duty. However, in October 2023 this share soared to 5% of all working hours in Israel. That is, while an average of around 3,200 workers were absent from work in a typical month from January to September 2023, most of them only part of the week, between October and December 2023 there were an average of around 130,000 workers per month absent from work, most of them fully absent. This is an unprecedented scale of reserve duty, at least during recent decades, and it constitutes a heavy burden on both reservists and employers. As we shall see below, this burden was not shared equally.

As the war progressed, the burden gradually decreased, and as of June and July 2024 it stood at approximately 1% of the labor force, or around 2% of men’s work hours (Figure 1). That is, “only” about 34,000 people of working age were absent from work each month due to reserve duty, imposing a loss of 1.16 million work hours per month. Even these numbers, while lower than during the height of the crisis at the end of 2023, are unprecedented, placing a considerable burden on workers and employers.[2]

Figure 1. Burden of reserve duty: Proportion of work hours lost due to reserve duty (burden on reservists and their spouses); age 25-64 (%)

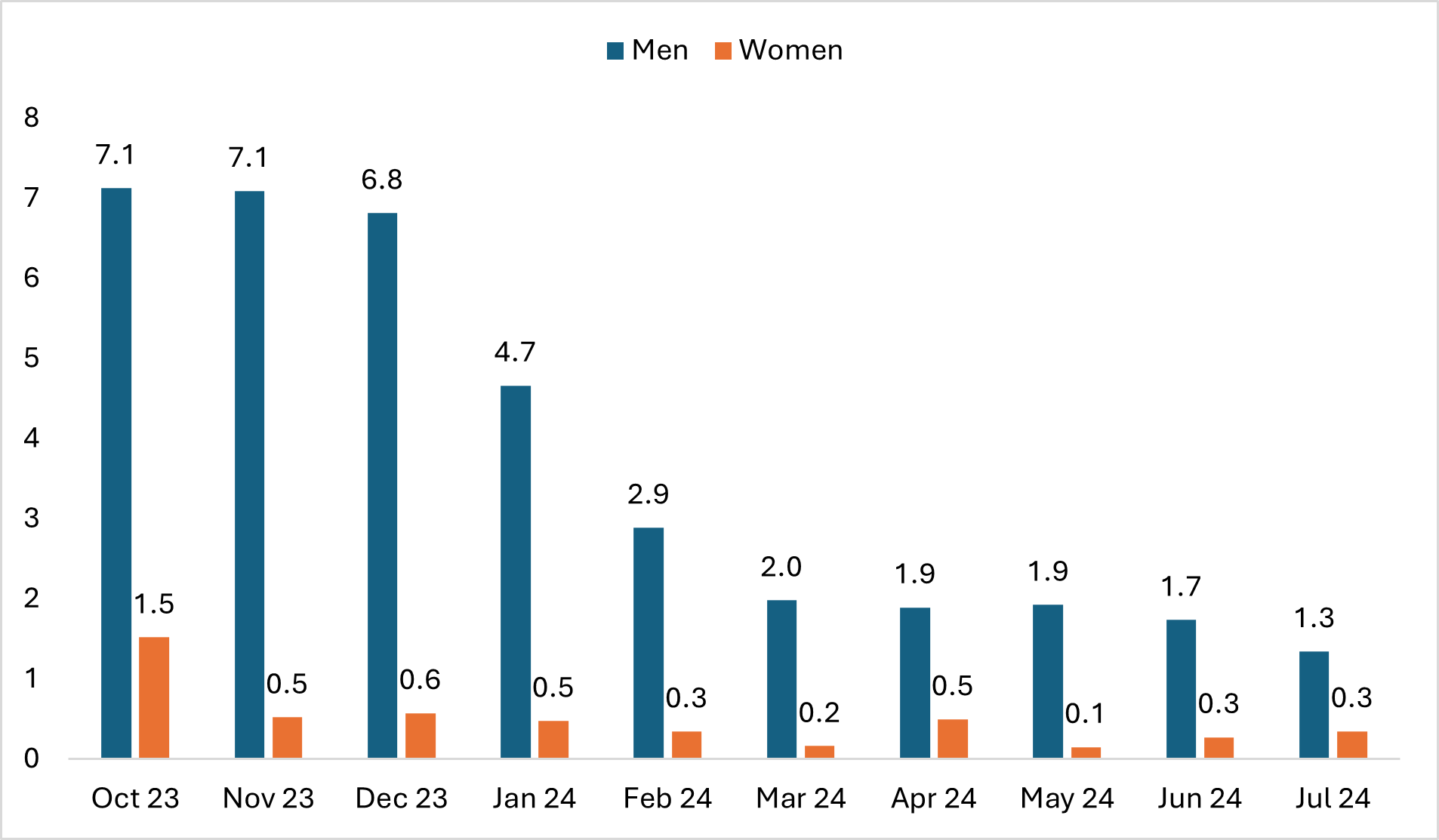

This burden is particularly prominent among non-Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Jewish men (7% of work hours in October 2023, 2% in July 2024).

Analysis by gender reveals that the direct burden of reserve duty on the working population is much higher among men than among women. While in October and November 2023, reserve duty resulted in a loss of around 7% of the work hours of men of working age (25-64 in Israel), the equivalent loss of work hours among women was only around 1%. As of July 2024, the burden had fallen to 1.3% among men and 0.3% among women. As we show below, the burden shouldered by women is mainly indirect, stemming from their spouses performing reserve duty.[3]

Figure 2. Burden of reserve duty: Proportion of work hours lost due to reserve duty (burden on reservists and their spouses); age 25-64, by gender (%)

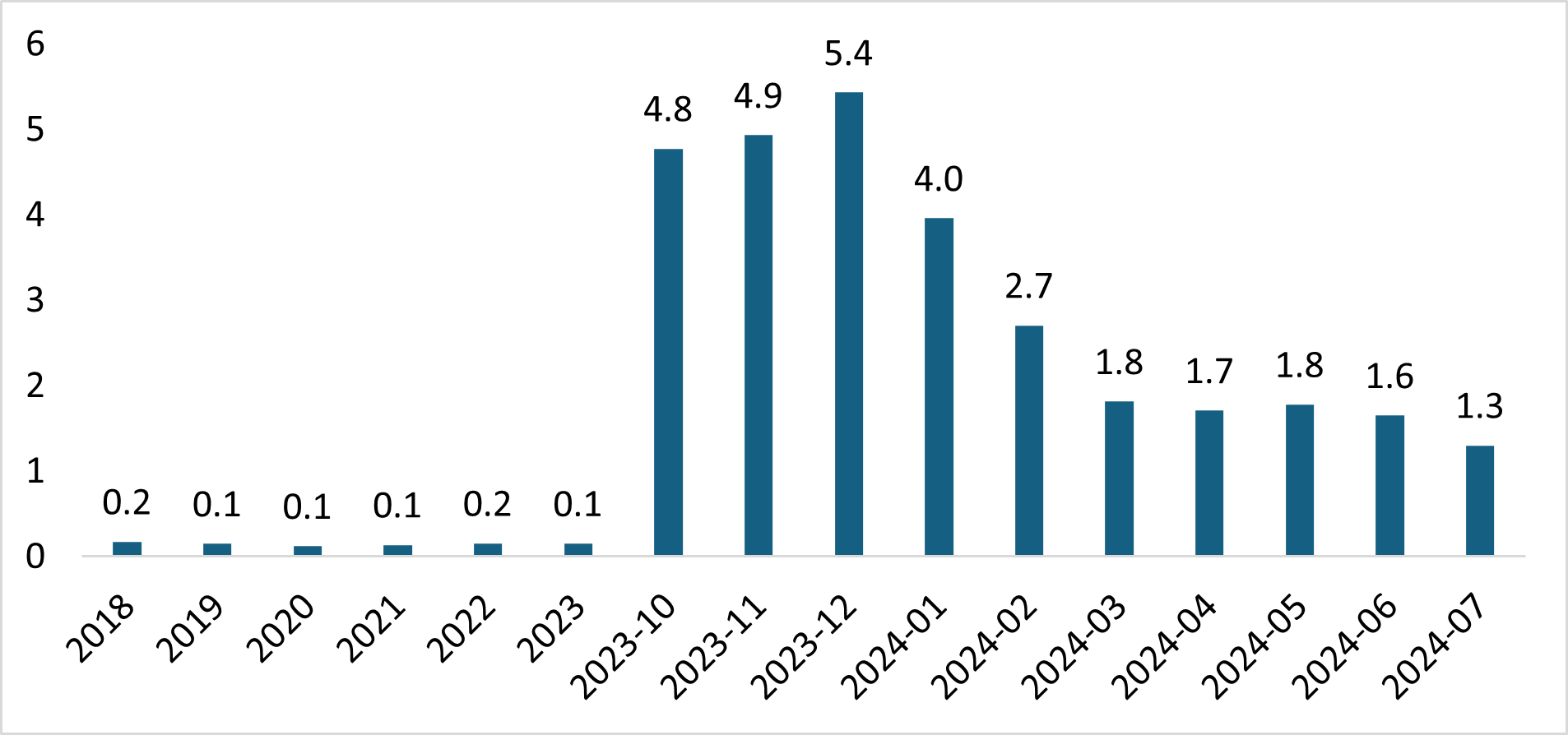

Extended periods of reserve duty by men are likely to place a heavy burden on households, due to the challenges of childcare. The data show that around 5% of the spouses of non-Haredi Jewish women were in reserve duty at the end of 2023, falling to around 1.3% over the course of 2024. This translates into more than 20,000 households in which one or both parents have been absent for several months, at an age when many couples are raising young children. Because the burden of reserve duty has stabilized over the most recent months for which data is available to us, it is reasonable to assume that assistance will also be needed with childcare in order to allow the households of those in reserve duty to continue to function for extended periods of time. Without such assistance, it is likely that over time we will see a decline in the functioning of these households in the labor market, or withdrawal from reserve duty.

Figure 3. Percentage of non-Haredi Jewish women whose spouses were in reserve duty, monthly average, 2018–2024 (%)

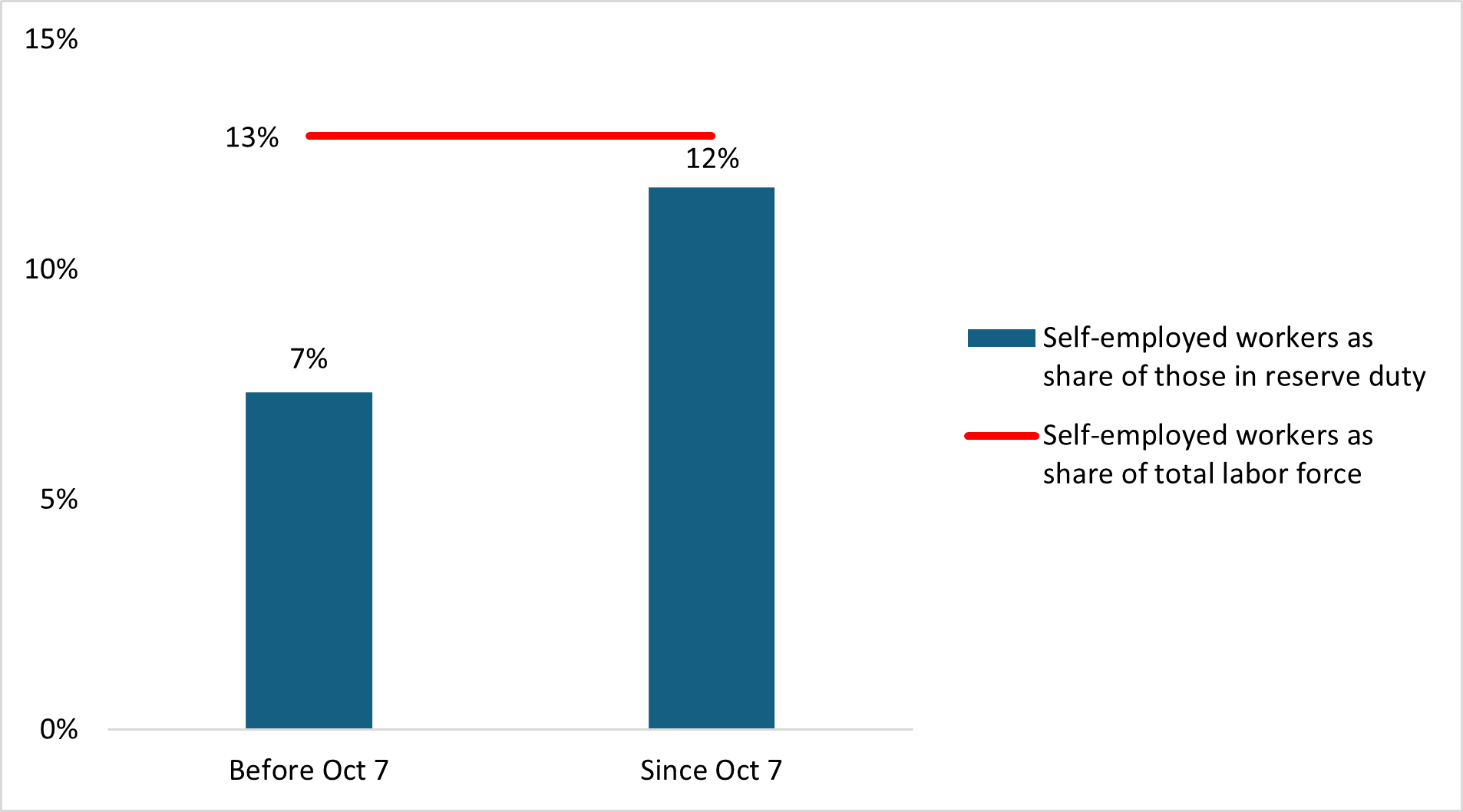

Our analysis shows that in an average month before the outbreak of the war, the proportion of self-employed workers absent from work either partially or fully due to reserve duty was negligible—around 0.05%, or just several hundred self-employed workers per month (similar to the situation among employees—0.1%, or several thousand salaried workers per month).[4] After the outbreak of the war, the share of self-employed workers in reserve duty jumped to 2.8% in the final months of 2023, or around 14,000 workers per month (again, similar to the rate among salaried workers of 3.5%, or around 130,000 workers per month). The number of workers absent from work due to reserve duty fell considerably over the course of 2024 among both self-employed and salaried workers.

This change in the burden of reserve duty is likely to have significant negative consequences for small-business owners. This is because unlike employees, who cannot be legally fired while in reserve duty (though there may be valid concerns about illegal layoffs), the law does not prevent customers of self-employed workers in reserve duty from finding other, more available suppliers instead, or from not renewing contracts with a supplier who is in reserve duty.

Figure 4. Percentage of those in reserve duty of working age who are self-employed, not including those engaged in household work and those of other working status

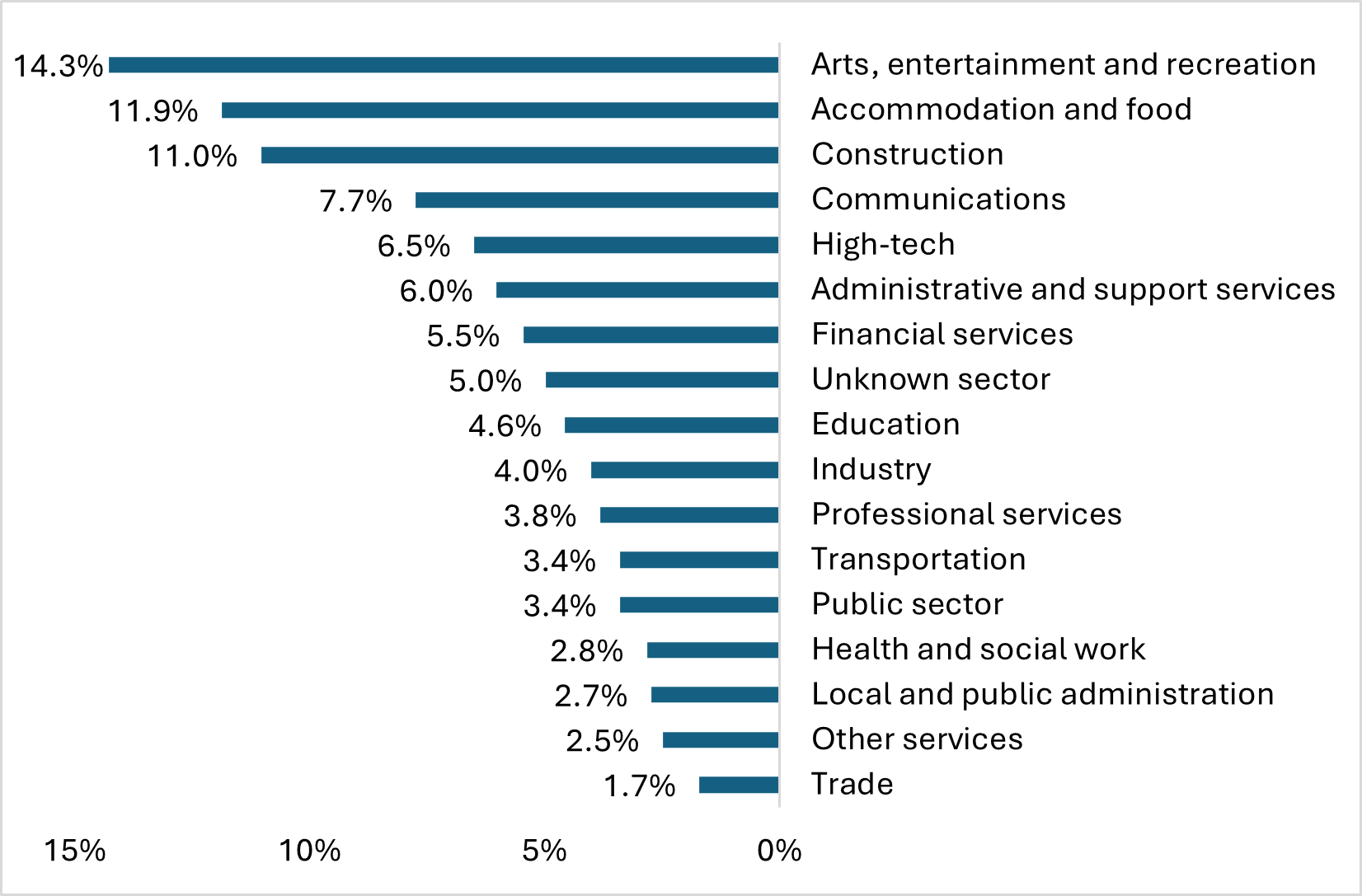

In October 2023, the burden of reserve duty on the labor market stood at around 5% of the total work hours. This burden was not shared equally among economic sectors, and some sectors lost more than 10% of work hours due to workers in reserve duty, while others suffered much lower losses of around 2–3%. Our analysis of the data shows that the sectors that suffered a greater loss of work hours were the arts, entertainment and recreation sectors (14% of work hours), accommodation and food (12%), construction (11%), and communications (8%). The high-tech sector[5] saw a decline of 7% in work hours due to the burden of reserve duty. By contrast, several sectors lost a smaller share of work hours, including wholesale and retail trade (1.7%), other services (2.5%),[6] and local and public administration (2.7%). The public sector (including, for the purpose of this analysis, the education sector and the health and social work sector, as well as the local and public administration sector) lost around 3.4% of work hours due to reserve duty in October 2023. The data show that all sectors had to deal with a sizeable share of workers absent from work due to reserve duty, though sectors that employ a higher proportion of young, non-Haredi Jewish men—some of them sectors with high productivity, and some dependent on seasonal or occasional employment patterns—were suddenly forced to shoulder a disproportionate and unprecedented burden of absent workers.

Figure 5. Work hours lost due to reserve duty as a percentage of work hours per economic sector, October 2023 (scale: 0–15%)

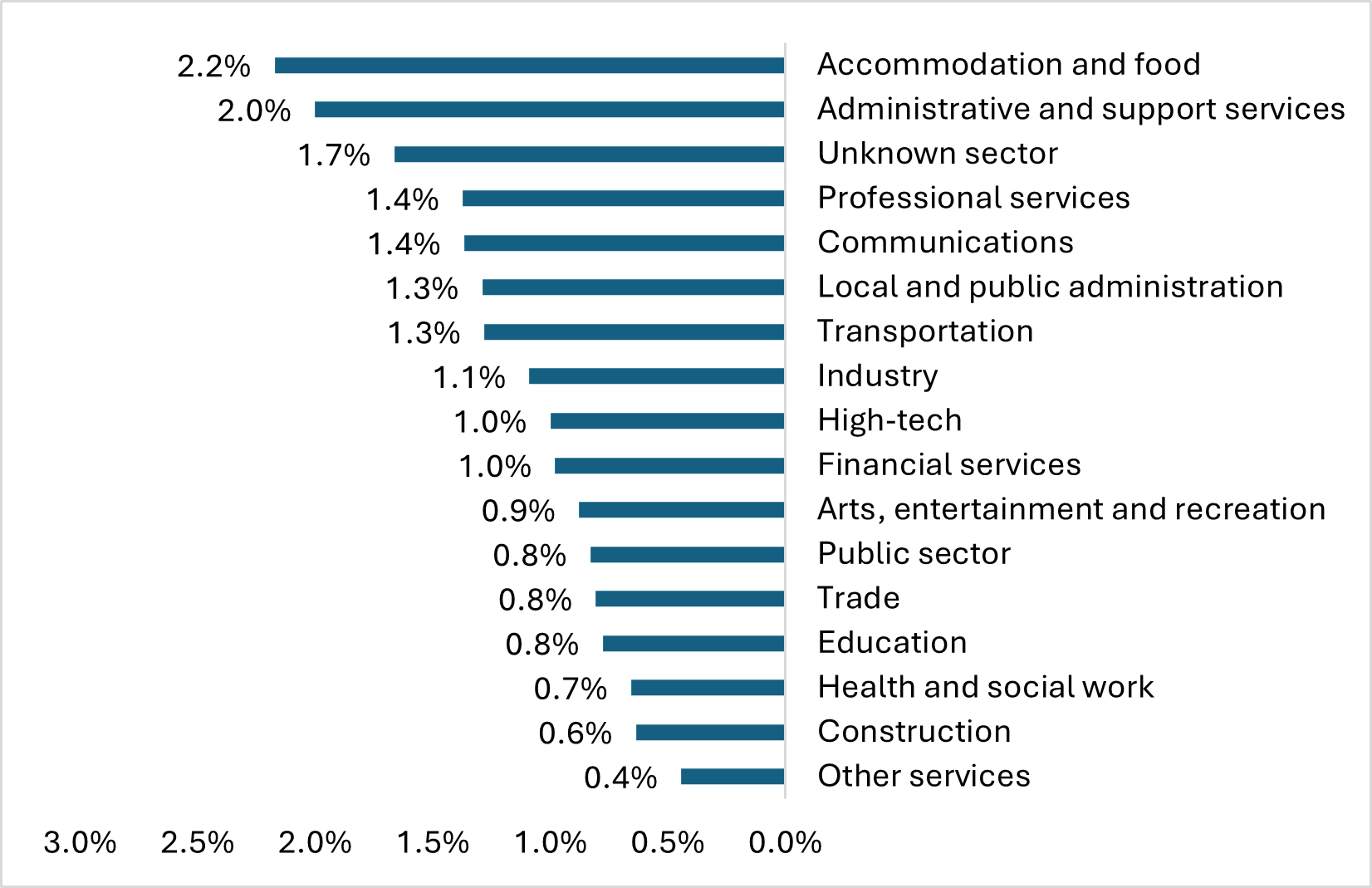

In the last three months for which there are available figures, May–June 2024, the picture for economic sectors has changed dramatically. The sectors most badly hit during this period only lost around 2% of work hours—the accommodation and food sector, which employs relatively young workers (2.2%), the administrative and support services sector (2%), and workers in unknown sectors (2%), who most likely have a weaker connection to the labor market. Over this period, the high-tech sector lost just 1% of work hours due to reserve duty, and the public sector, 0.8% . The analysis shows that the majority of the labor market stabilized around a share of 1% of workers in reserve duty, an unprecedently high percentage, but much lower than the peak that came at the end of 2023. The outliers are several sectors that are more dependent on young, non-Haredi Jewish male workers, which are still suffering from a higher burden.

Figure 6. Work hours lost due to reserve duty as a percentage of work hours per economic sector, May–July 2024 (scale: 0–3%)

The analysis shows that across the labor market as a whole, the burden of reserve duty has stabilized in recent months (June–July) at around 1% of work hours, down from a peak of 5% in October 2023 following the outbreak of the war. This still represents a considerable burden on Israel’s economy, for workers, employers, and public expenditure.

Two “back-of-an-envelope” calculations demonstrate this impact. First, in terms of GDP, it is difficult to assess the impact of reserve duty, as compensation paid to reservists is counted as part of GDP, and thus the increase in public expenditure is likely to partially balance out the damage done to business output. However, it is possible to estimate the expected negative impact on business output using reasonable assumptions: a year of reserve duty at the level of 1% of work hours distributed uniformly throughout the business sector will likely cost NIS 7.9 billion, around 0.64% of business output.

Another calculation, which attempts to take into account other components of direct damage to business output, is based on estimates made by the Ministry of Finance for the overall cost to Israel’s economy of a month of reserve duty served by an individual.[7] The bulk of the damage to the economy from reserve duty stems from the loss of work inputs to the business that loses access to its worker, and is legally prevented from hiring another worker to replace them. In addition, the calculation includes the cost to the individual from loss of seniority at work, and the cost to their household of the loss of work suffered by their spouse. Other costs—such as the risk of death and the emotional price paid by reservists—are not included in the calculation, and thus it is clear that the cost to society is much higher than that presented here.

The Ministry of Finance calculates (based on a derivative of the average wage) that the monthly cost to the economy for each person in reserve duty is NIS 48,000 for a man and NIS 32,000 for a woman. According to the gender mix of reservists seen during the Iron Swords War, we estimate that the average cost to the economy per reservist is NIS 45,000 per month. This adds up to a considerable overall cost to the economy. In terms of the state budget alone, expenditure on compensation to reservists in 2023 reached NIS 8.2 billion, and in 2024 an additional almost NIS 4 billion has been budgeted (most likely, insufficiently)—this, compared with an average annual outlay of NIS 1.6 billion for the five years preceding the war.[8]

This is doubly significant in light of the fact that the burden of reserve duty is not shared equally. Young people, (non-Haredi) Jews, and men serve in greater numbers. From an overall perspective, this means that the damage to the economy is disproportionately borne by the sectors that employ these population groups, such as the accommodation and food sector, and in addition to the high-tech sectors, which are characterized by high productivity; thus, damage to the activity of these sectors is liable to also have a significant negative impact on exports and GDP. In addition, because reserve duty is not a one-time event but a continuing burden, it is likely that even if the state fully compensates reservists for their loss in earnings (an assumption that, as noted, is unlikely to be fulfilled in the case of self-employed workers, who make up around 12% of reservists), the price that they and their families pay is still considerable. Among the prices worth mentioning in this context are that many reservists face a real risk of injury or death; they are absent from their homes, often for many months at a time; and they are required to cope with significant physical and mental difficulties.

In the current circumstances, in which the security needs of the State of Israel are not expected to lessen significantly in the foreseeable future, efforts should be made to expand the share of the population that performs reserve duty—for example, by increasing the application of mandatory conscription in the Haredi population, or by encouraging volunteering for regular military service among the Arab population. This will make it possible to increase the share of the burden borne by soldiers in regular service, and reduce the burden borne by reservists.

[1] This study was conducted using the research environment of the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), which is based on files containing individual records that were prepared for research purposes by the CBS and from which all identifying details have been removed. A complementary analysis was made using data from the public usage files (PUF) from the CBS’s 2023 Labor Force Survey and data from press releases published on the CBS website.

[2] Initial data indicate that the burden remained at about the level of 1% of workers during August as well. See: CBS, “Labor Force Survey Data, August 2024,” press release, September 23, 2024.

[3] For more details about women in reserve duty, see: Jerry Almo, Data About Female Reservists During the Iron Swords War, Knesset Research and Information Center (August 2024).

[4] The estimation of the average monthly number of self-employed workers in reserve duty is around 250, but this is a very “noisy” estimation as it is based on just tens of observations, and it is possible that the true number is higher or lower. The estimation of the average number of employees in reserve duty is more stable, and stands at around 3,000 per month in 2023 before the war, and close to 9,000 as a multi-year average for 2018–2023.

[5] Using the definition in the Perlmutter Report (Report of the Committee on Increasing Human Capital in High-Tech [Hebrew]), not including the communications sub-sector.

[6] This category combines several relatively small service sectors, including computer and telephone repairs, members’ organizations, representative business organizations, and cosmetic treatments.

[7] Chief Economist’s Department, Alternative Pricing of the Increase of Personnel in the IDF (Ministry of Finance, March 2023). The bulk of the cost in the Ministry of Finance calculation is based on the loss of work input to the economy from reservists, and not on the price in terms of GDP or budgetary cost, because according to the nationally accepted accountancy rules, the payment of salaries to reservists from state funds are counted in the calculation of GDP, even though it does not represent a real economic activity in the usual sense.

[8] Key to State Budget, Ordinance 15.10.01.08—Reserve Duty Compensation: https://next.obudget.org/i/budget/0015100108/2024 [Hebrew]; Key to State Budget, Ordinance 15.10.01.09—Reserve Duty Compensation: https://next.obudget.org/i/budget/0015100109/2024 [Hebrew].