Workforce Participation of Haredi Yeshiva Students Under the Exemption Age

This study describes the employment trends among men registered in ultra-Orthodox yeshivas between the ages of 18-25. The findings are based on a reported work, or "legal work," so it is very likely that this is an underestimation of reality.

Photo by: Nati Shohat/Flash90

Until recent events[1], a legal framework was in place under which ultra-Orthodox men (Haredim) were exempt from military service, under the condition that they study in yeshivas full time—at the age of 26, known as the "exemption age," their exemption from IDF service no longer hinges upon continued study in the yeshiva, also allowing them to join the workforce. Beyond this, Haredi men who choose to study in yeshivas would sign a Ministry of Defense affidavit confirming their Torah study and committing themselves not to work before the age of 22. The option of working is open to them from age 22 onward, provided that the student is married, and only outside of yeshiva study hours (this commits them to studying in yeshiva, for 45 weekly hours, or 40 hours if in kollel).[2] In other words, as long as the yeshiva student is not married, he is forbidden to work even after the age of 22.

This study, based on administrative data from 2022[3], describes the extent of employment among men registered in Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) yeshivas between the ages of 18 and 25 (as mentioned, from the age of 26, they are permitted to work without conditions related to military service)[4].

It should be noted that the findings in the review are based on reported work that can be tracked in official state data ("legal work"), so it is very likely that this is an underestimation of the reality, because some of the students work in unreported, odd jobs.[5]

- How many yeshiva students work?

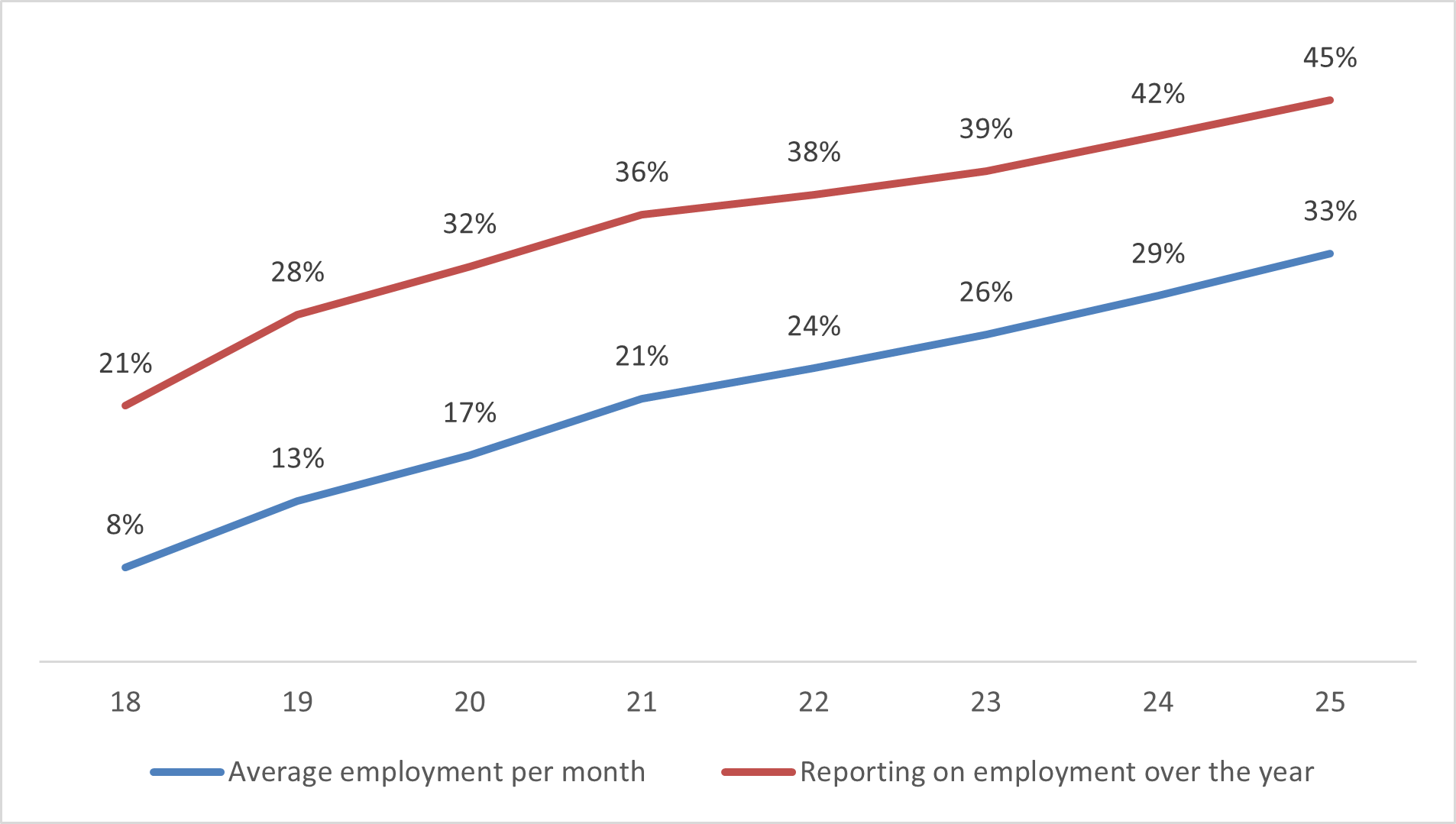

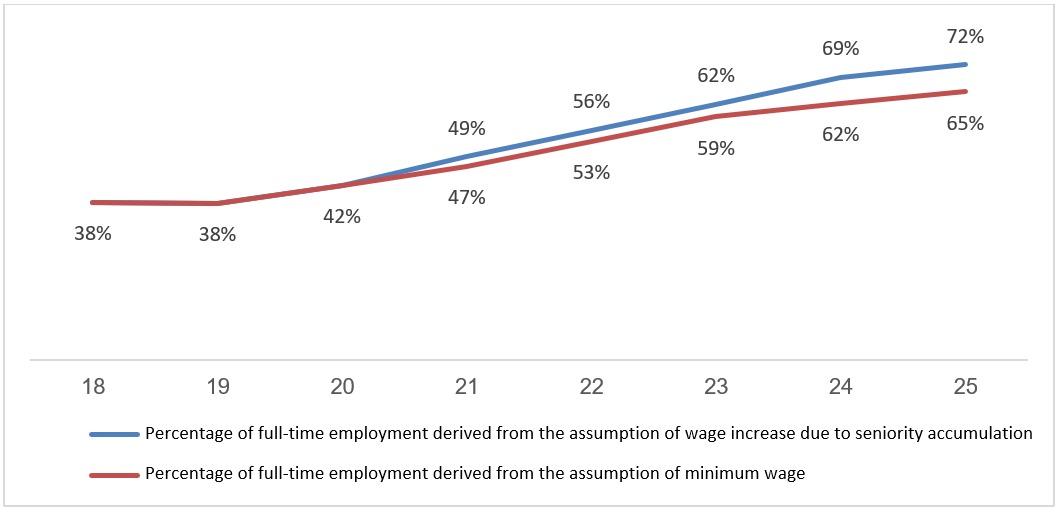

In most cases, young yeshiva students[6] are not regularly employed throughout the entire year.[7] Figure 1, which estimates the participation rate of yeshiva students in the labor market, depicts two estimates: the first estimate (the lower line) describes the average number of yeshiva students engaged in employment in an average month, while the second estimate (the upper line) describes the percentage of yeshiva students who reported their income to the tax authority at least once during the year. The implication of the first estimate is to provide an assessment of "quality employment," which considers the period of employment throughout the year, whereas the second estimate indicates the percentage of yeshiva students who worked at least once during the year and received reported income.

The findings indicate that 8% of 18-year-olds were employed per month (on average), while 20% of them were employed at some point during the year. The employment rate gradually increases up to the age of 25, where, on average, one-third of yeshiva students are active in the labor market each month, with 45% of this age group having worked at least once during the year.

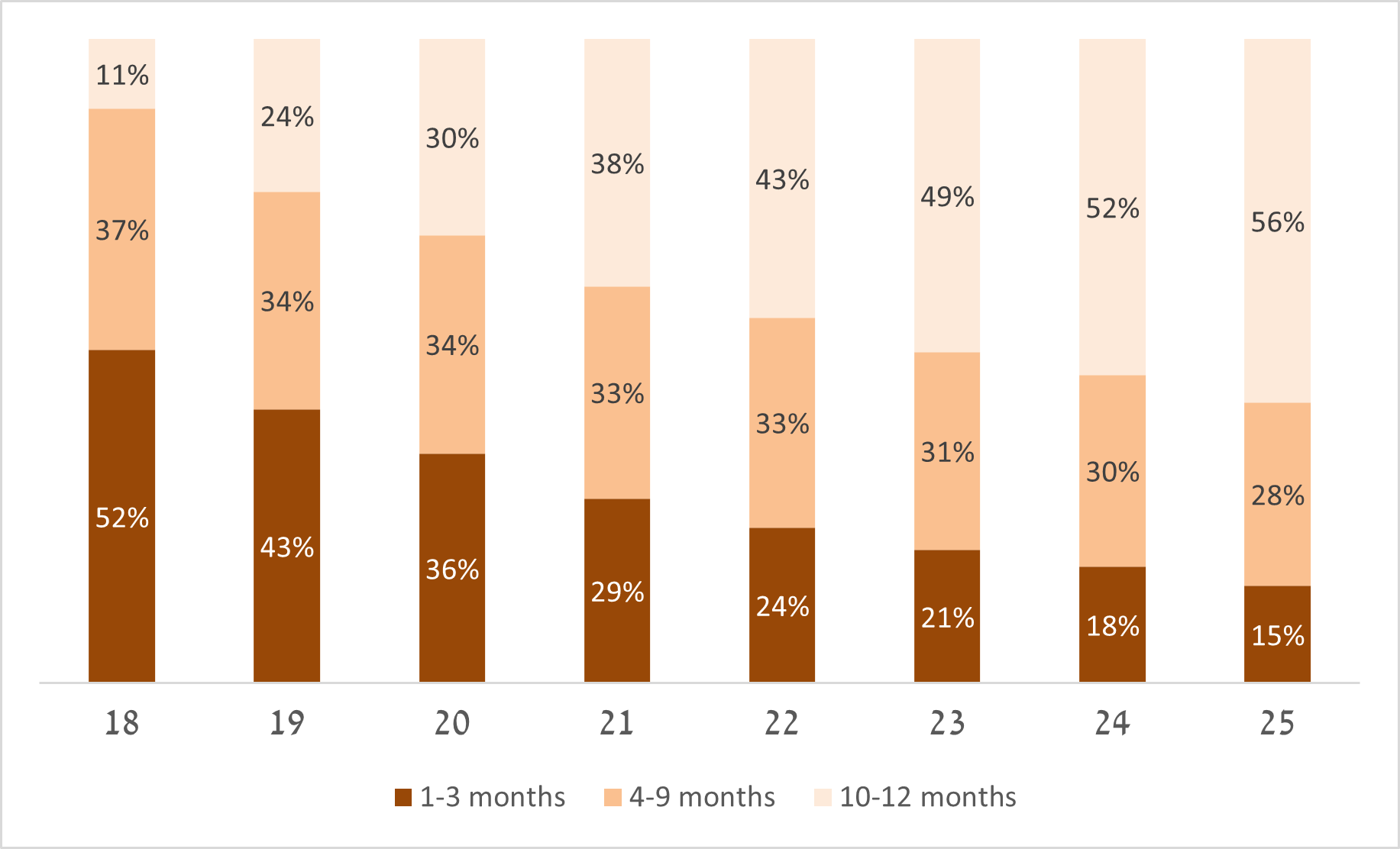

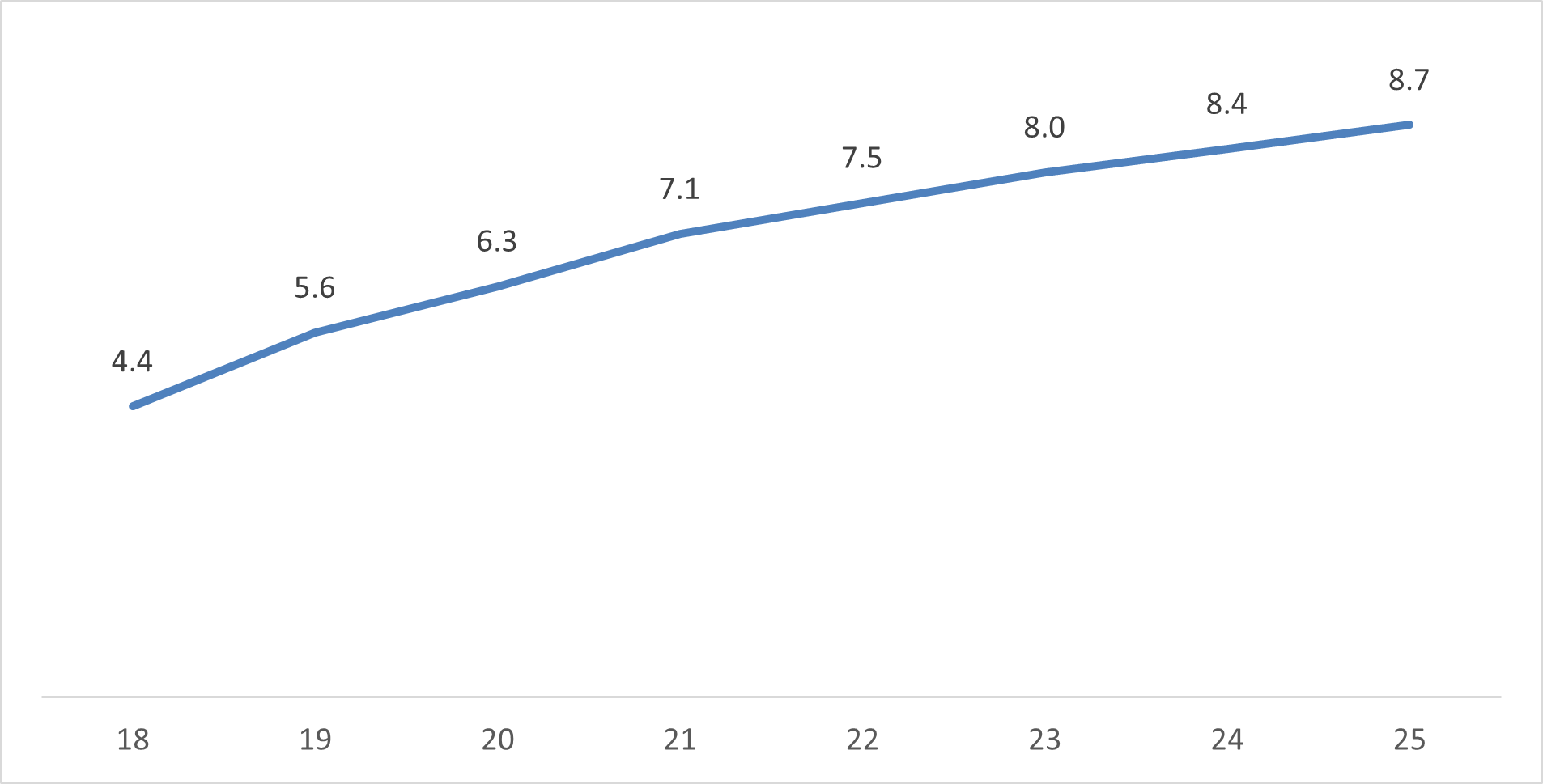

Figure 1B also shows an increasing labor market presence with advancing age. Among employed 18-year-olds, 52% worked for 1-3 months, with this rate decreasing to 29% among 21-year-olds and 15% among 25-year-olds. Conversely, 11% of employed 18-year-olds worked for 10-12 months a year, with this rate rising to 38% among 21-year-olds and 56% among 25-year-olds. Figure 1C, which describes the average number of months worked among employed yeshiva students, shows that employed 18-year-olds worked approximately 4.5 months per year, increasing to about 7 months by age 21 and almost 9 months by age 25.

It should be noted that one might expect to see a sharp relative increase in the transition from ages 20-21 to ages 22-23, given that, as mentioned, only from the age of 22 do yeshiva students receive official permission to work beyond their study hours in the yeshiva (if they are married). However, the data indicate a gradual rather than sharp increase between age groups, which may suggest employment integration norms that do not necessarily align with state laws. In other words, although yeshiva students are prohibited from working until age 22, and from this age onward they are allowed to work only if they are married and concurrently fulfill their study obligations, the data still indicate a significant percentage of workers in the age group where work is strictly prohibited (18-21), with the percentage increasing with age.[8]

Figure 1a: Yeshiva students in the workforce, by age

Figure 1b: Distribution by the number of months worked among yeshiva students employed in the labor market, by age.

Figure 1C: Average number of months worked among yeshiva students employed in the labor market, by age.

2. How much do they earn? Salary levels and employment rates

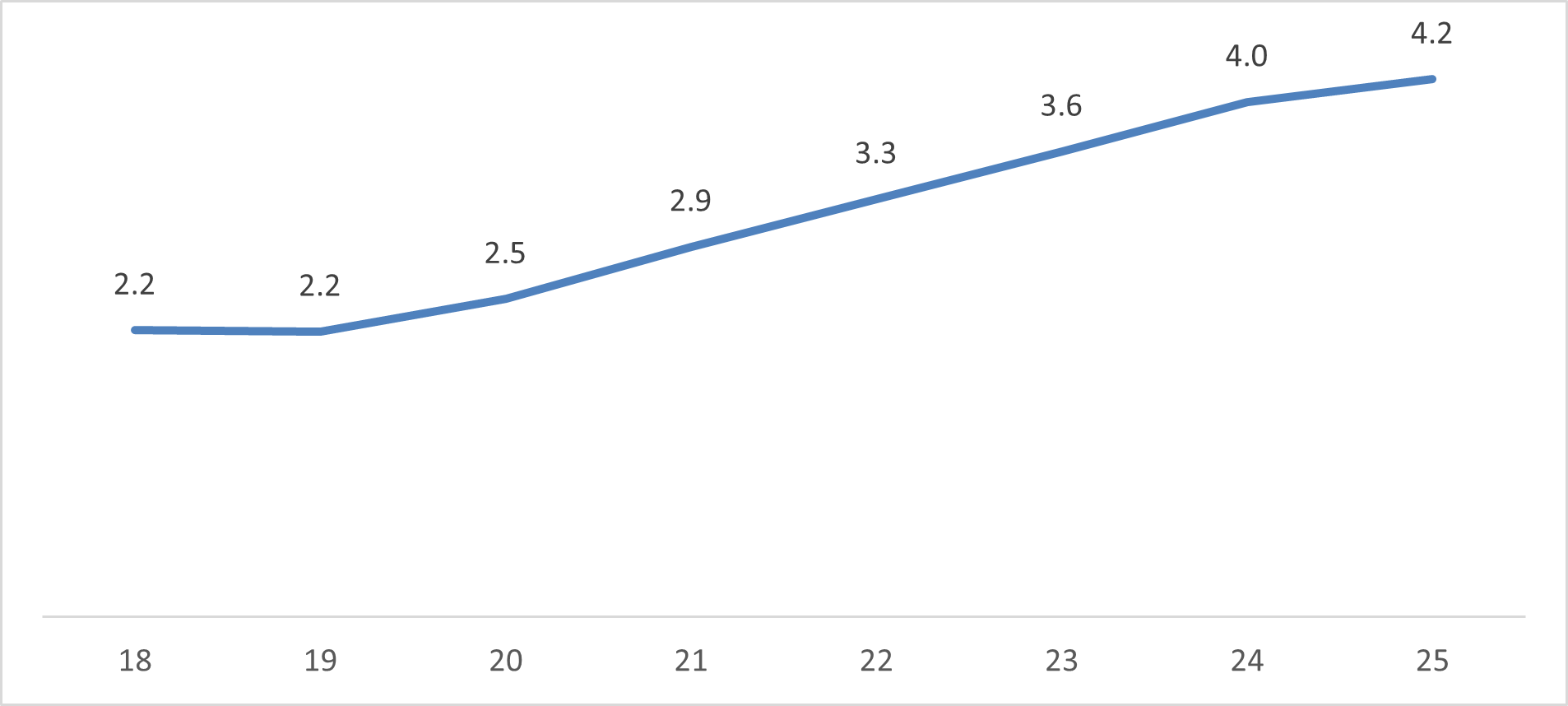

Figure 2 shows that the salary level among yeshiva students aged 18-19 who are in the workforce is approximately NIS 2,200. This salary gradually increases to approximately NIS 4,200 per month by the age of 25.

Figure 2: Average monthly income of yeshiva students in the labor market (in NIS thousands).

It should be noted that administrative data do not include information on working hours (nor do they provide data on hourly wages). Therefore, we rely on the data from Figure 2 to estimate the employment rates of yeshiva students who are in the workforce. In this section, we refer to two main scenarios: in the first scenario, we assume that yeshiva students earn the minimum wage at all ages up to 25; in the second scenario, we assume that the wage increases due to increased seniority at work (minimum wage at ages 18-20, 5% above minimum wage at ages 21-23, and 10% above minimum wage at ages 24-25).

Figure 3 indicates dramatic findings regarding the employment rates observed. As mentioned, until the age of 22, yeshiva students are prohibited from receiving any compensation for work. The findings indicate that yeshiva students aged 18-20 participating in the workforce are employed under both scenarios at minimum wage and do so at 40% employment rates, while yeshiva students aged 21 in the workforce work at approximately half-time employment rates.

According to the minimum wage assumption scenario, the employment rate is 62% among yeshiva students aged 23, 69% among those aged 24, and 72% among those aged 25.

According to the seniority accumulation scenario, the employment rate is 59% among those aged 23, 62% among those aged 24, and 65% among those aged 25.

Figure 3: Estimated percentage of full-time employment for yeshiva students in the workforce, by age:

3. Work period

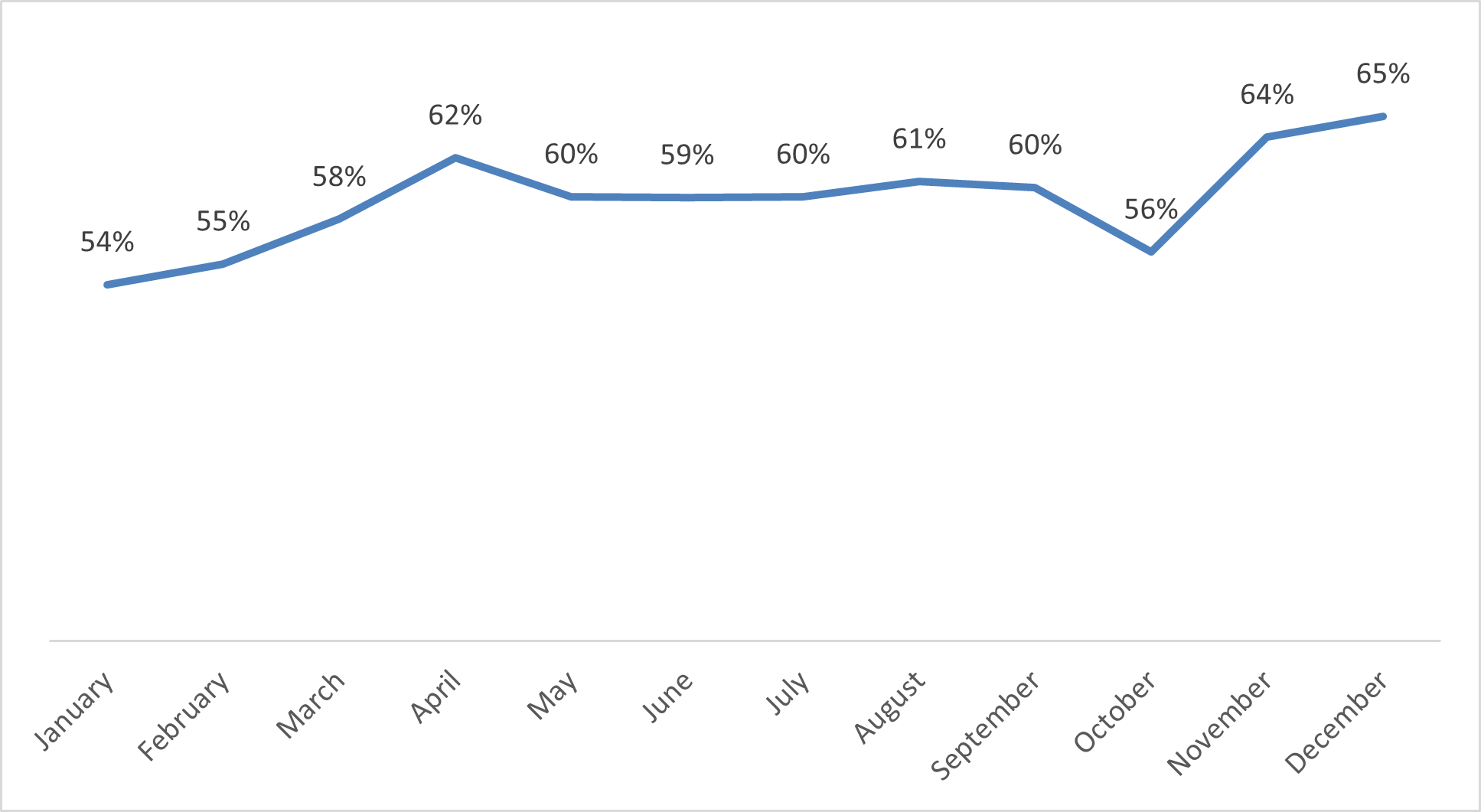

This section addresses the claim that yeshiva students work during their vacation between study terms, known as "Bein Hazmanim" breaks. These breaks occur during the month of Nissan (approximately 4 weeks during March-April), from Tisha B'Av until the beginning of Elul (approximately 3 weeks during July-August), and from after Yom Kippur until Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan (approximately three weeks during September-October).

Figure 4 shows that the variation in employment rates across the months of the year is not significant, and the "Bein HaZmanim" months do not stand out as having exceptionally high employment rates (there is a slight increase in April, but also a decrease in October). It was found that the months with the highest relative employment rates are November and December when there are no breaks at all (even compared to April, which was a full vacation month in 2022), and there is even a decrease in employment in October, during which the break occurs.

Figure 4: Employment rate among yeshiva students who were employed in 2022, by month

4. What types of work do yeshiva students do? Distribution by economic sector

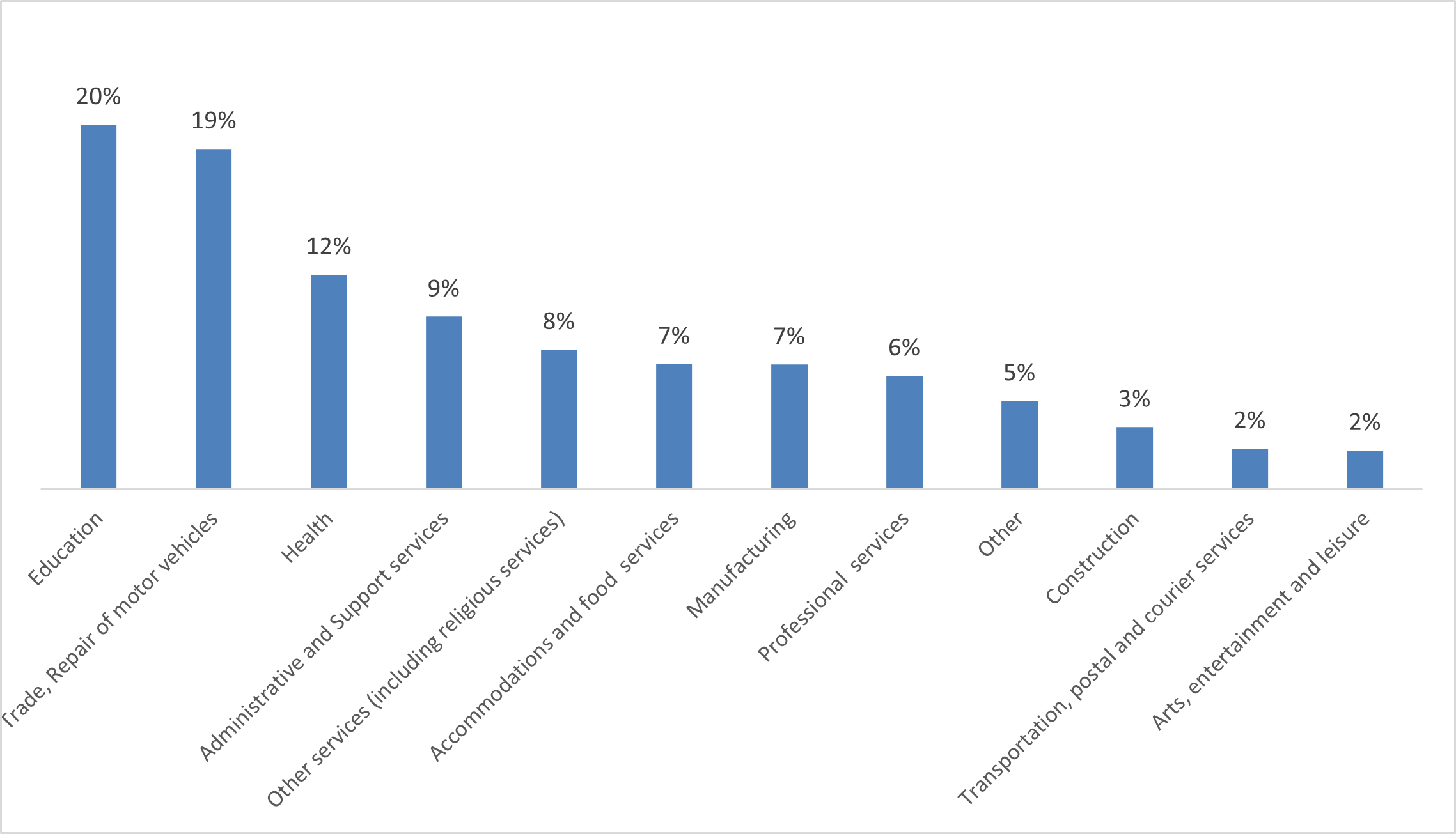

A fifth of working yeshiva students aged 18-25 work in the education sector, while another fifth are in the vehicle sales and repair sector. An additional 8% are in the "other services" sector, which includes religious services.

Figure 5: Sectoral distribution among yeshiva students aged 18-25 in the workforce

- Do only married men work?

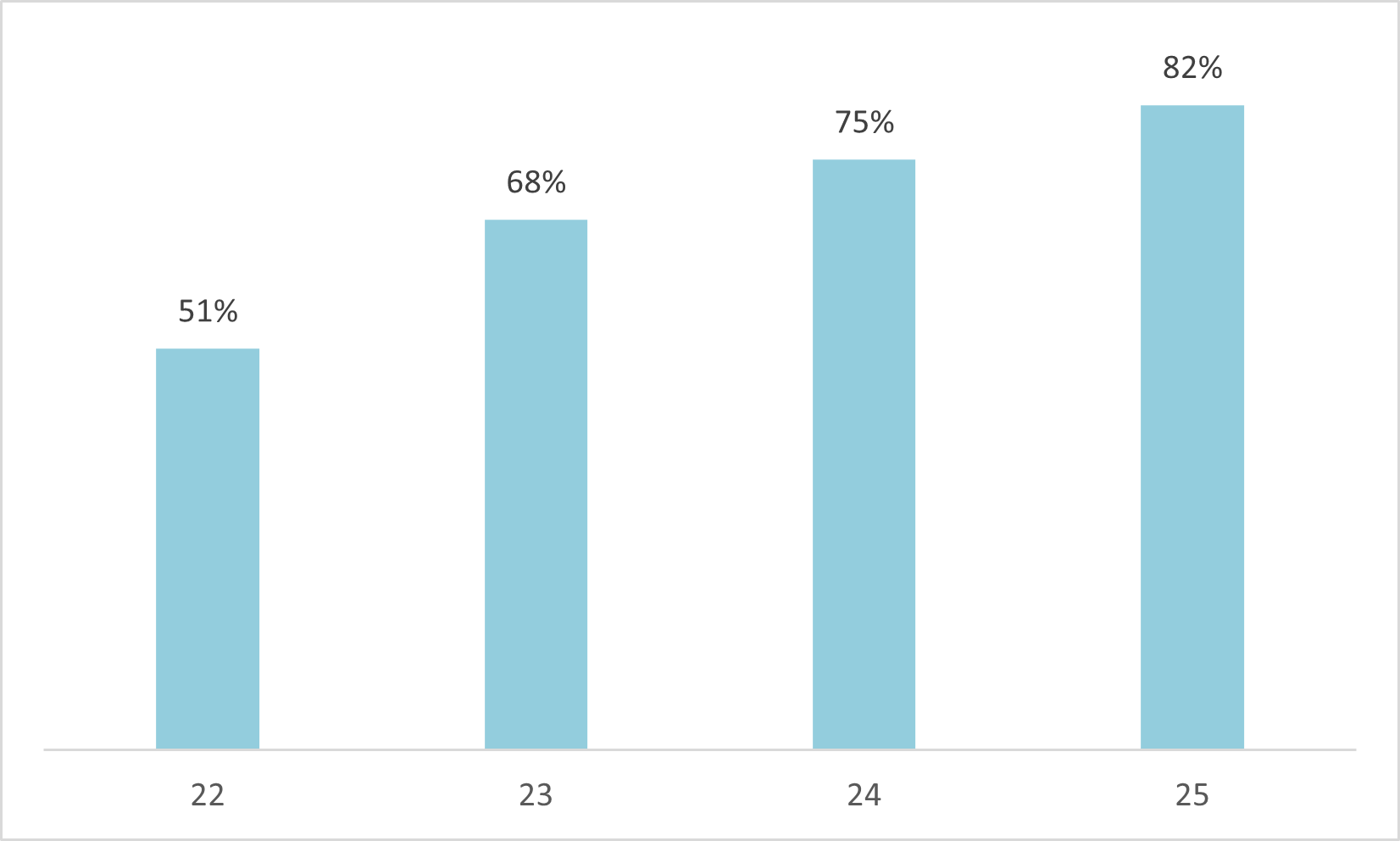

As mentioned above, under the law, yeshiva students are permitted to work from the age of 22 only if they are married (and after study hours), while in other cases they are forbidden to work. Figure 5 depicts the percentage of married men[9] among workers age 22 and up. According to the findings, only about half of the workers at age 22 are married, while the percentage of married workers increases with age (68%, 75%, and 82% respectively up to age 25). This means that a significant proportion of yeshiva students who are not legally allowed to work are in fact working.

Figure 5: Percentage of married yeshiva students in the workforce, by age

2. Characteristics of working yeshiva students by streams

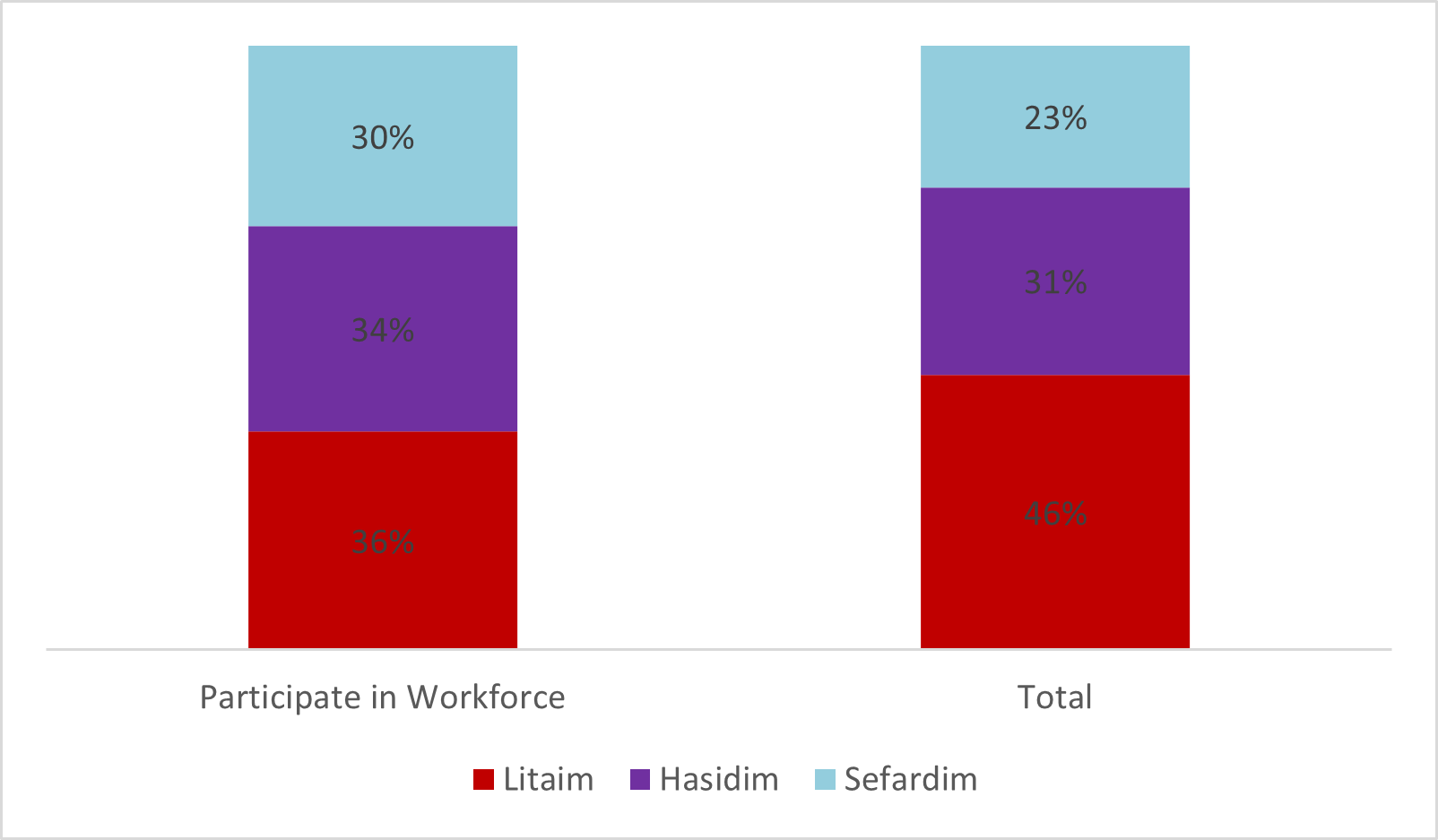

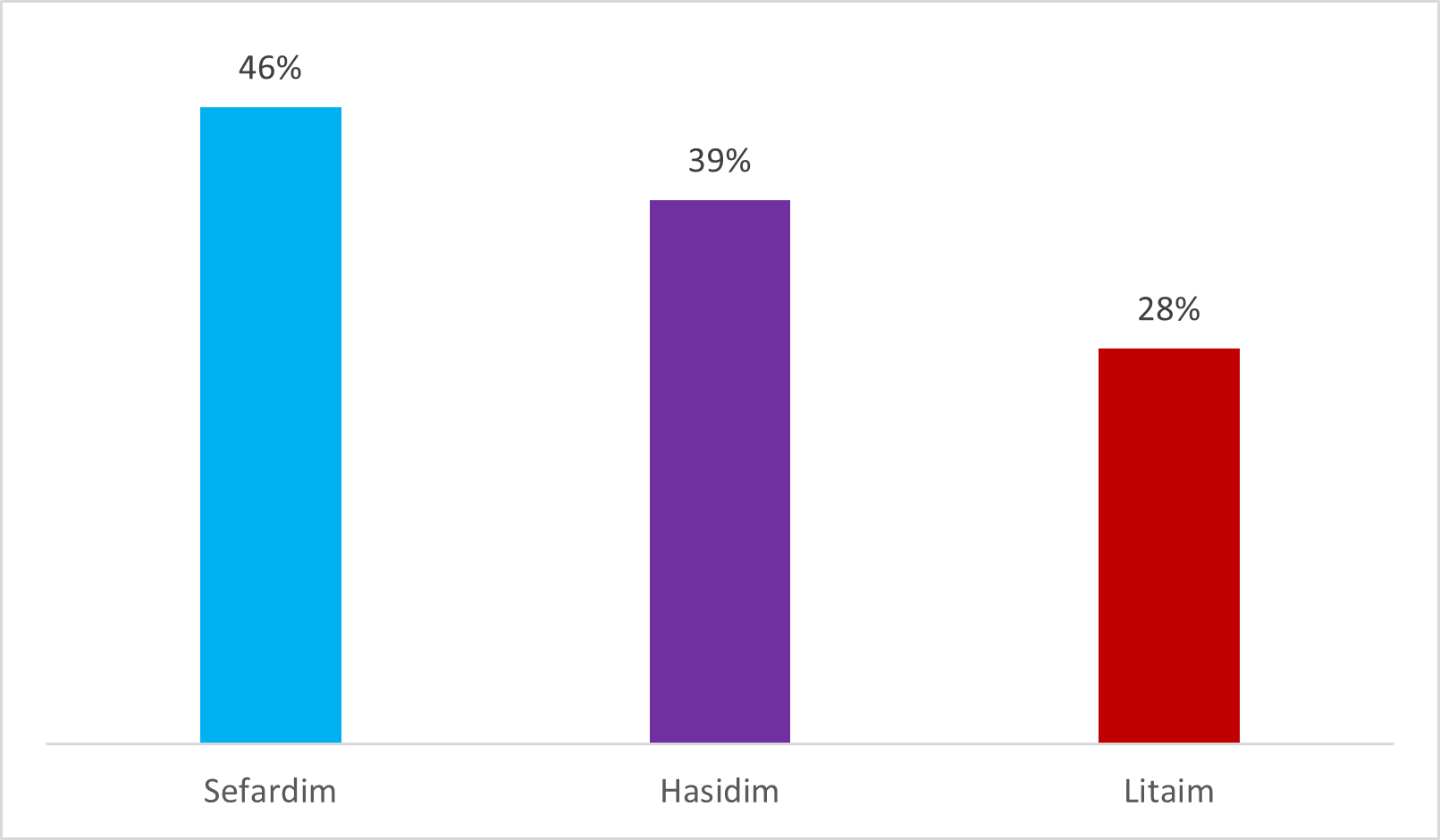

Relative to their population size, men from the Lithuanian stream are more likely to learn in "Great Yeshivas" (Yeshivot G'dolot), for post-high school age students before marriage, (after studying in "Small Yeshivas" (Yeshivot K'tanot), for high-school age students) compared to Hasidim and especially compared to Sephardim. Therefore, Lithuanians are overrepresented in yeshivas compared to other streams (Lithuanians constitute about 46% of the individuals surveyed in this study compared to 31% among Hasidim and 23% among Sephardim, while the population distribution is roughly equal).

The distribution of those employed (who, as mentioned, appear in the Tax Authority records) by subgroups does not correspond to their proportion among yeshiva students. The findings show that Sephardi yeshiva students are overrepresented among those in the workforce, and so are Hasidim, although to a lesser extent. Lithuanians are underrepresented relative to their proportion among yeshiva students (though many of them are still in the workforce). In other words, Sephardim, and to a lesser extent Hasidim, are more likely to be in reported employment compared to Lithuanians (although in absolute numbers, there are more Lithuanians in reported employment compared to Sephardim).

Figure 7a: Distribution by streams among working yeshiva students compared to the general distribution by streams

Figure 7b: Percentage of yeshiva students reported as employed in the workforce, by streams

Clear laws have been established regarding the employment of yeshiva students under the age of 26.[10] Specifically, yeshiva students are committed not to work before the age of 22, and they may work beyond this age only if they are married and outside of yeshiva study hours. In this study, we have shown that these laws are not enforced and that a significant amount of employment exists that is essentially illegal. It should be noted that the findings in this study likely constitute an underestimation, as we cannot assess the extent of unreported employment. If this is indeed the case, many (perhaps very many) yeshiva students who receive an exemption from military service fail to comply with the commitment they signed as a condition for receiving the exemption. In other words, a significant proportion of yeshiva students do not wait for the official exemption age to join the workforce, and as mentioned, this may be just the tip of the iceberg.

[1] In July 2023 the legal framework which permitted the exemption of Haredim from military service expired, thereby changing the status of military aged Haredim to draft-dodgers (Arikim)

[2] In the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) society, unmarried men study in a large yeshiva, while married men study in a kollel.

[3] Cross-referencing of databases from the Tax Authority and a file of details from religious institutions, with individual data hidden for privacy reasons. It should be noted that the total number of individuals in this study is 61,047 males aged 18-25 (inclusive) in 2022, studying in large Haredi yeshivas or kollels.

[4] It is worth noting that after the exemption clause in the Security Service Law expired in June 2023, there is effectively no exemption age. As the Supreme Court clarified in June 2024, in the absence of a legal basis for exemption, mandatory service applies from the age of 18 for anyone without a permanent exemption or service deferment.

[5] See Malchi ("From the World of Yeshivas to the World of Work", 2024), who found that among 17- to 23-year-olds, 21% of those studying in regular yeshivas and 75% of those studying in "soft" yeshivas (comprising 18% of the total respondents) are employed. This study does not rely on administrative data and may therefore include "working in the black".

[6] Therefore, the reference to the population of students in yeshivas will be "yeshiva students," which also includes married students studying in kollels.

[7] Regarding self-employed individuals, who make up approximately 3% of all yeshiva students who work, there are no data available on monthly work hours. Therefore, it is assumed that they worked for 12 months, and their annual income is divided by 12 for calculation purposes.

[8] It should be noted that this is reported work; thus, actual employment attendance is likely to be much greater.

[9] The divorced and widowers have been removed from this part

[10] As previously noted, as of July 2023, the legal framework which permitted the exemption of Haredim from military service expired, thereby changing the status of military aged Haredim to draft-dodgers (Arikim)

- Tags:

- Ultra-Orthodox,

- Economy and Governance,

- Haredi Conscription,

- Judaism and Democracy,

- Minorities,

- Ultra-Orthodox-Economics,

- ultra-Orthodox/Haredi,

- Economy and Politics,

- Economy and Society,

- economy,

- Behavioral Economics,

- Ultra-Orthodox in Israel Program,

- The Joan and Irwin Jacobs Center for Shared Society,

- Center for Governance and the Economy