A Master Plan for Ultra-Orthodox Employment in Israel

- Written By: Dr. Gilad Malach, Doron Cohen, Haim Zicherman

- Publication Date:

- Number Of Pages: 123 Pages

- Center: The Joan and Irwin Jacobs Center for Shared Society

- Price: 45 NIS

IDI’s policy recommendations for integrating Israel’s ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) population into well-paying employment increasing rates of participation in the labor market.

IDI’s Master Plan for Ultra-Orthodox Employment in Israel presents policy recommendations for integrating Israel’s ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) population into well-paying employment and facilitating a continued rise in employment rates in this sector. This plan was devised as a result of extensive research conducted by IDI in cooperation with the National Economic Council of the Prime Minister's Office, under the leadership of IDI's Doron Cohen, former Director General of the Finance Ministry, and Prof. Eugene Kandel, Chairman of the National Economic Council. A brief summary of the plan can be found below.

This publication was made possible by the generous support of The Russell Berrie Foundation

In formulating IDI’s Master Plan for Ultra-Orthodox Employment in Israel, the members of IDI's research team surveyed the existing situation and policies, identified barriers to change, analyzed opportunities that can promote change, and proposed a series of operational policy recommendations that can be implemented by the government. As part of the research process, they conducted roundtable meetings with representatives of the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of the Economy, the Education Ministry, the Prime Minister’s Office, the Council for Higher Education, and the Bank of Israel. These sessions contributed greatly to the ability to understand the issue thoroughly, devise multiyear objectives, and analyze tools that can be used to attain these objectives.

The result of this process was a comprehensive plan that includes the following:

- An overview of the programs and mechanisms for encouraging ultra-Orthodox employment that are currently operated by the government and its partners in the third sector and the private sector

- A quantitative and qualitative update of employment objectives for ultra-Orthodox men and women for 2025

- An analysis of the barriers that stand in the way of achieving these objectives

- Recommendations for ways to overcome these barriers and achieve the desired objectives.

At a Glance

Ultra-Orthodox Jews accounted for 11% of the population of Israel in 2014, and this figure is expected to rise to 18% by 2034. The consistent demographic growth of this sector has economic ramifications both for its members and for the country as a whole. Consequently, ultra-Orthodox employment has become a key issue in Israeli public discourse and policymaking over the last decade.

As a result of the low employment rate and low income that characterizes this sector, most ultra-Orthodox households are below the poverty line. Given the consistent growth of this community, ultra-Orthodox poverty has macro effects on tax revenues, benefit payments, consumption, and GDP.

IDI’s Master Plan for Ultra-Orthodox Employment in Israel recommends that the State of Israel revise its employment policy for the ultra-Orthodox sector for the coming decade, shifting its focus to include the objective of increasing employment in fields that offer higher-paying jobs, rather than focusing only on integrating ultra-Orthodox Jews in the workforce and increasing their rate of employment. This change would ensure that entering the work force will actually enable ultra-Orthodox Israelis to earn a decent wage and live comfortably. In addition, it would contribute to increased productivity and a more equitable distribution of the tax burden, which would benefit Israel's economy and society as a whole.

Current Data on Ultra-Orthodox Employment

Over the last decade, tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox Israelis have taken advantage of the services of employment centers and programs that have been set up with their specific needs in mind. As a result, between 2003 and 2014, the share of ultra-Orthodox men with gainful employment rose from 36% to 45% and the share of ultra-Orthodox women with gainful employment rose from 51% to 71%. (In contrast, the national average for other Israeli Jews in 2014 was 82.5%.) However, due to the prevalence of part-time and low-paying jobs for members of this sector, the average monthly wage of ultra-Orthodox employees was less than 80% of the average wage in the economy.

Ultra-Orthodox Employment Targets for 2025

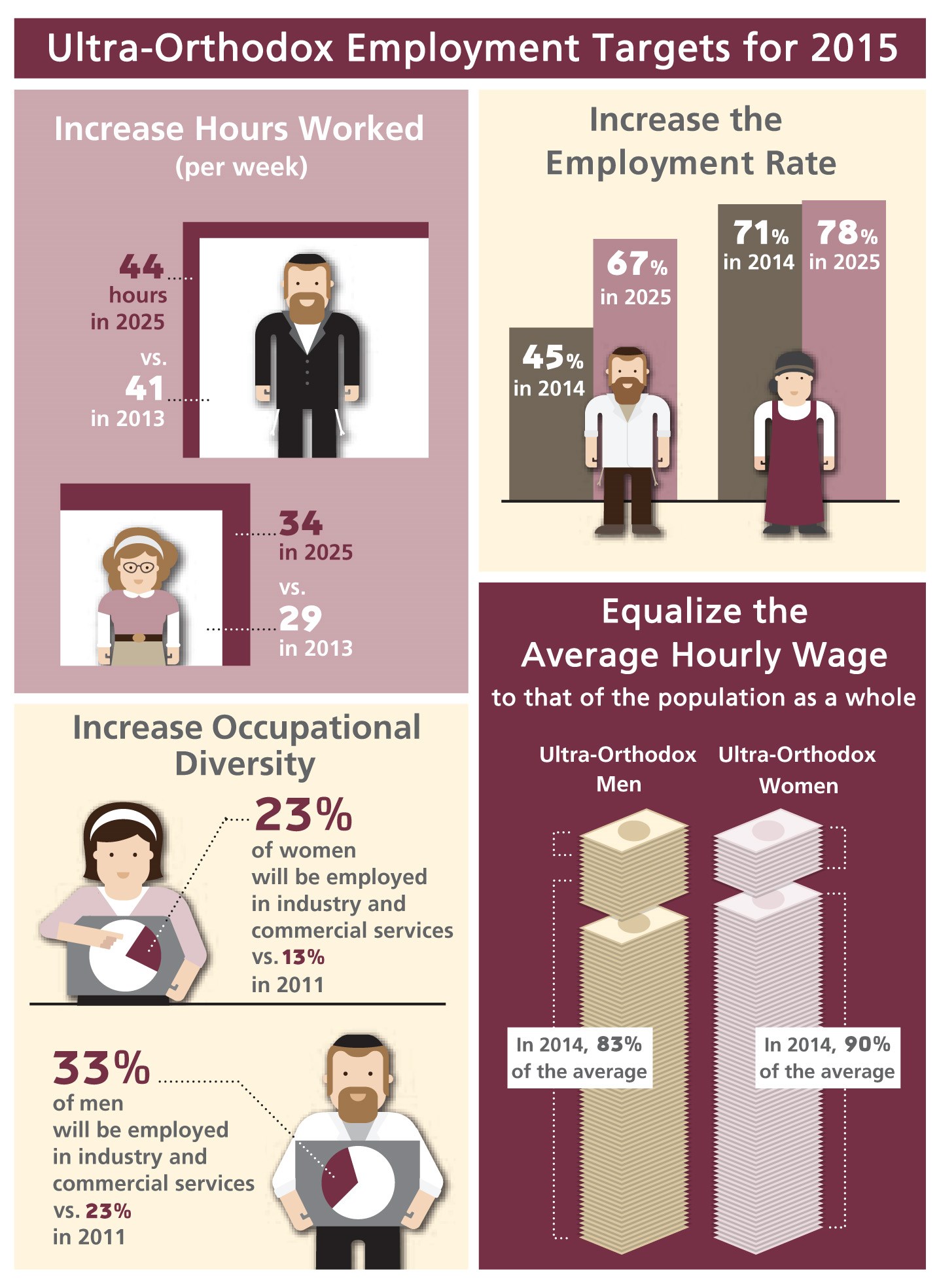

In 2010, the Israeli government set 63% as the desired rate of employment for ultra-Orthodox men and women by the year 2020. IDI's master plan recommends revising the objectives for the next decade (until 2025) to go beyond employment rates and to include reference to fields of employment and increased wages. We recommend the following targets for increasing participation in the labor force, weekly hours worked, occupational diversity, and wages earned:

- By 2025, the desired employment rate for ultra-Orthodox Jews is 67% for men and 78% for women. (This would be an increase from 45% of ultra-Orthodox men and 71% of ultra-Orthodox women in the workforce in 2014.)

- Weekly hours work should increase to 44 hours of work per week for men and 34 for women. (In 2013, ultra-Orthodox men worked an average of 41 hours a week, while women worked an average of 29 hours a week.)

- By 2025, we recommend that 23% of ultra-Orthodox women and 33% of ultra-Orthodox men be employed in industry and commercial services. (This would represent an increase from 13% and 23% for men and women respectively in 2011.)

- The average salary of ultra-Orthodox employees should be brought in line with the average salary of all employees. (In 2014, the average hourly wage for ultra-Orthodox women was 90% of the wage of the general population, while the average wage for ultra-Orthodox men was only 83% of the wage of the general population.)

Diversifying fields of employment, an increase in work hours, and higher hourly wages would have a positive effect on three levels:

- Government: Increased tax revenues, as a result of better-paying jobs

- Society and the Economy: higher GDP, stronger growth, and a more equitable division of the tax burden

- Ultra-Orthodox Individuals and Families: higher income, greater economic security, and an intergenerational transfer of capital and assets.

Barriers and Opportunities

In order to increase productivithy within the ultra-Orthodox community, policy makers must overcome a number of hurdles and take advantage of several opportunities.

Barriers to employment in the ultra-Orthodox sector include:

- Knowledge barriers: A lack of general studies, matriculation certificates, and professional qualifications

- Cultural barriers: Large family size, relatively late entry into the labor force, and reluctance to work in a mixed-gender and mixed religious-secular environment

- Barriers to better-pay: Limited demand for ultra-Orthodox workers on the part of employers, obstacles to entry into the civil service, a preference for part-time employment among workers, a lack of information about employment possibilities and job openings, and poor occupational training.

Opportunities that could be utilized include:

- Resolution of the conscription issue: The government's exemption of tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox yeshiva students aged 22 to 28 from military service now allows young men in this age group to leave the yeshiva and legally enter the workforce.

- Changes in awareness: Deepening poverty has forced the ultra-Orthodox community to recognize that real change is necessary.

- Internal initiatives: Many initiatives to promote higher quality employment have already been launched within the ultra-Orthodox community itself.

- Government support: The Israeli government is willing to invest in ultra-Orthodox employment far more heavily than in the past and increasingly understands the importance of steering the ultra-Orthodox towards better-paying jobs.

Policy Recommendations

We recommend three growth engines that can increase income levels, encourage longer work hours, and improve the ability of ultra-Orthodox employees to receive promotions. These include expanding occupational training and academic programs, improving vocational counseling services, and increasing the willingness of employers to hire ultra-Orthodox workers.

A. Quality Training for the Workplace

Recent years have seen a substantial increase in the number of occupational tracks offered by ultra-Orthodox seminaries for women, the number of ultra-Orthodox high schools for boys that include secular studies in their curriculum, and the number of ultra-Orthodox applicants to college and university programs in computer science and engineering. These programs all provide extensive preparation for the workforce. What is important now is to ensure that training focuses on better-paying employment. This can be accomplished by the following:

- Allocating earmarked funds for new ultra-Orthodox boys' high schools that include secular subjects in the curriculum

- Creating new programs that will make it possible for graduates of the ultra-Orthodox education system, both male and female, to complete the requirements for a matriculation certificate

- Support for expanding and improving tracks beyond teacher-training programs at seminaries for ultra-Orthodox women

- Developing programs for distance learning in basic subjects such as English and mathematics

B. Improved Vocational Counseling and Training

The vocational counseling currently provided by the government-sponsored employment development centers for the ultra-Orthodox sees entry to the workforce itself as the goal, without considering the position's salary. College and university programs for the ultra-Orthodox do not emphasize job placement, which makes it difficult for graduates to find work. The current study also found that ultra-Orthodox employees who do manage to break through the glass ceiling into better-paying jobs encounter cultural barriers in their new workplace.

The following steps are recommended in order to shift the focus away from vocational counseling and training alone and towards better-paying employment:

- Creating a system of incentives to motivate vocational counseling centers to direct ultra-Orthodox jobseekers toward average-income and high-income jobs, train ultra-Orthodox candidates for a wider variety of occupations, and help ultra-Orthodox Jews who are already working obtain promotions or better jobs

- Encouraging academic programs designed for the ultra-Orthodox sector to prepare students for the work force by means of special courses, student jobs, and placement services linked with ultra-Orthodox employment development centers

- Devising a program to prepare and place ultra-Orthodox employees in the civil service, business, and academia, which will include a fund to encourage ultra-Orthodox social and business entrepreneurship.

C. Increasing Demand for Ultra-Orthodox Employees in High-Wage Sectors

The negligible number of ultra-Orthodox employees in important sectors, notably hi-tech, is a challenge that requires special attention as well as a commitment by employers to hire ultra-Orthodox employees. Employers allege a market failure, claiming that the vocational counseling and training provided to the ultra-Orthodox are out of sync with the needs of the market. For its part, the government provides incentives to those who employ ultra-Orthodox workers but does fails to stipulate salary levels; as a result, most ultra-Orthodox employees are paid only the minimum wage.

The following measures will promote better-paying employment for the ultra-Orthodox, particularly in the business sector:

- Drafting a covenant in which employers will undertake to hire ultra-Orthodox workers. This covenant, which will be signed by leading figures in the business community and launched under the auspices of the President of Israel, will include provisions for counseling, monitoring, and oversight of the process of hiring ultra-Orthodox workers for well-paying jobs.

- Strengthening the connection between employers, vocational counseling centers, and the government in order to align supply and demand in preferred areas of employment.

- Developing a system of grants that will motivate ultra-Orthodox Jews to target occupations that are in demand and pay average to high salaries.

Conclusion

Integrating Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews into the upper rungs of the labor market is a national priority that poses a challenge for policymakers and for Israeli society as a whole. Despite the impressive success in getting the ultra-Orthodox to enter the labor market and increasing employment rates among ultra-Orthodox men and women in recent years, current policies have not been able to extricate the sector from its deep poverty. The salaries of ultra-Orthodox workers remain low and do not provide real economic and social security.

Setting objectives for better-paying employment and pursuing these goals by implementing the full set of recommendations presented above could increase the labor productivity and wages of Israel's ultra-Orthodox workers. This new chapter in the integration of the ultra-Orthodox into the Israeli economy would benefit the ultra-Orthodox community, Israel's economy, and Israeli society as a whole.