Can a Criminal Defendant be Banned From Forming a Government?

Minister Gideon Saar's proposed bill preventing a criminal defendant from forming a government is unprecedented, but so is the reality in Israel. A comparative survey of the statutory provisions in various countries that apply when the head of the executive branch is suspected or convicted of a criminal offense: It turns out that in most democracies the legal situation is ambiguous.

A look at the constitutions of various countries and political cases that have taken place in the past reveals that the legal provisions are frequently ambiguous. Cases in which the head of the executive branch is suspected or convicted of criminal activity, although no longer so rare today, continue to pose a new challenge to the judicial, political, and public systems, as well as, of course, to the individual in question.

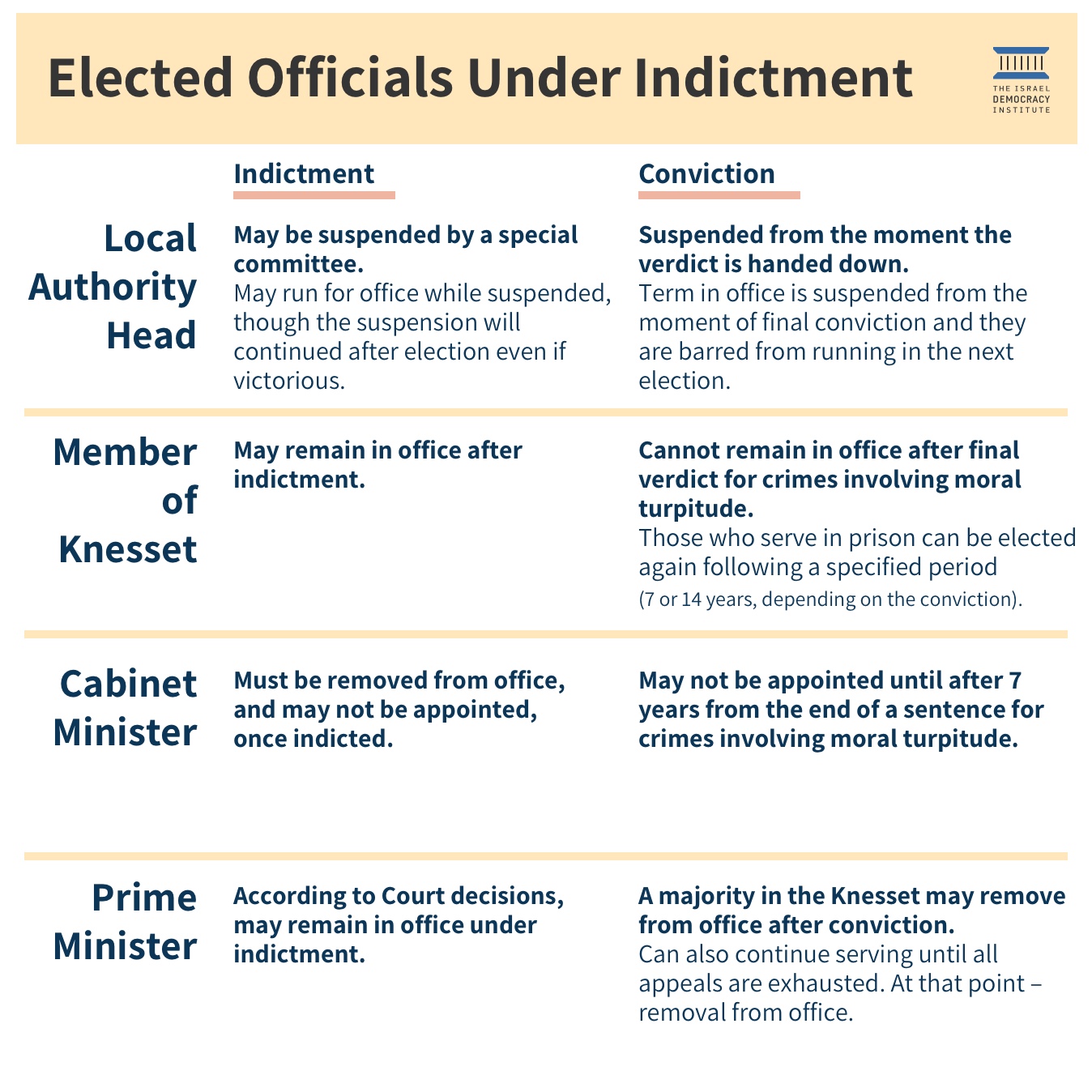

Even though the situation in Israel today is not a fictional scenario, and there have already been prime ministers who were the subject of a criminal investigation during their term of office, the statutory language remains vague and leaves a wide margin for both the prime minister and the Knesset to weigh political and public considerations with regard to what course should be taken in such a situation.

Parliamentary Governments

Great Britain

In Great Britain, as in Israel, an incumbent prime minister can be the subject of a criminal investigation and even face criminal trial. There is no specific statutory provision as to how the prime minister and/or Parliament should act in this case. Even though police investigators have paid visits to 10 Downing Street (when Tony Blair was prime minister), no British prime minister has ever been indicted and tried for a criminal offense.

Italy

In general, Article 96 of the Italian constitution stipulates that the prime minister and other Government Ministers bear criminal liability for crimes committed in the course of fulfilling their duties, that is – within the domain of their ministerial responsibility (for example, abuse of authority). Both houses of parliament must give their consent before proceedings can be initiated against the prime minister or any other minister with regard to acts committed by dint of their position. Under the current constitutional arrangement, there is thus no overall obstacle barring the investigation and trial of a prime minister or other senior officials. Recent years, however, saw several attempts to grant the prime minister and other members of the Government, temporary immunity.

These initiatives took place when Silvio Berlusconi was prime minister and was facing several criminal charges. The original proposal was to adopt a controversial mechanism of temporary immunity, of the president, the prime minister and other senior officials as long as they were in office, to exempt the president of the republic, prime minister, and other senior officials from criminal investigation and trial. According to the law, which, incidentally, was struck down three times as unconstitutional, all criminal proceedings against these elected officials would be suspended as long as they continued in office.

The Italian experience is particularly interesting because of the repeated attempts to legislate temporary immunity. As noted, the idea was initiated when Silvio Berlusconi was facing a number of criminal charges, including tax evasion, seducing a minor, and obstruction of justice. When the second version of the law was passed, in 2008, all of the investigations against Berlusconi were suspended, as were the trials that were already in progress. After the Court struck down the law, criminal proceedings were resumed. But this was not the end of the story. Berlusconi made a third attempt to enact a law to protect himself. After he resigned as prime minister in 2011, the criminal cases and proceedings against him were reinstated. Despite this, he ran for the Senate in 2013. He was barred from political activity for six years, only after being convicted and sentenced to a year in prison (commuted into public service on account of his advanced age). Even this did not put an end to his political career: indeed, he was elected to the European Parliament in 2019.

Denmark

In Denmark, the law does not specifically relate to a criminal investigation of the prime minister. However, Article 57 of the Danish Constitution does provide for parliamentary immunity, which applies to the prime minister as a member of parliament. Under this section, parliament must consent before one of its members can be put on trial. To date this provision has never been tested, and no prime minister has faced criminal charges.

Norway

The prime minister may be the subject of a criminal investigation and stand trial. The law has no special provisions for t a procedure to remove or suspend the prime minister in this situation. According to a document produced by the Knesset Research and Information Center, the Norwegians evidently rely on their political culture and norms and expect that parliament would vote no confidence against a prime minister suspected of criminal wrongdoing.

Sweden

In principle, an incumbent Swedish prime minister can be the subject of a criminal investigation and even stand trial. However, the investigation and prosecution must be carried out at the national—rather than the local—level.

The Swedish constitution refers specifically to the case in which past or serving ministers, including the prime minister, commit a criminal offense as a result of gross negligence in the performance of their duties. In this case, a criminal investigation can be authorized by the Constitutional Committee of the Rijksdag; the case must be tried by the Supreme Court, sitting in a special panel as specified in the constitution.

Presidential Regimes

The United States

One might have expected that the United States, the land of the constitution and the law, would have a specific law about the conditions for criminal proceedings against a sitting chief executive, but in fact the situation is far from clear. The Constitution does not grant the president sweeping immunity from criminal proceedings, but neither does it state anything to the contrary. It does provide a mechanism for the president’s impeachment and removal from office, but this is essentially a political proceeding, and not a substitute for indictment and trial. The constitutional grounds for impeachment are treason, bribery, and “serious crimes and misdemeanors.” The impeachment mechanism is designed to protect the institution of the presidency and its prestige, but it does not exempt presidents from criminal liability for their actions.

Because the law does not define the procedure to be followed in these circumstances, the US Supreme Court must rule on such matters. The Constitution does not relate specifically to criminal charges. Since to date, no American president has been indicted, the issue has never been decided, and there is no legal precedent to follow.

France

Article 68 of the French Constitution states that the President of the Republic is exempt from liability for actions taken during his term of office, with two exceptions: an act that constitutes a fundamental breach of his duties (high treason) and acts that fall under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court—genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The president can be removed from office only in an open vote of both the National Assembly and the Senate, by an absolute majority of their members; he is tried by the High Court of Justice. The accepted interpretation is that, as long as he remains in office, the president enjoys immunity against both criminal charges and civil suits, other than in the exceptions noted above.

This immunity, which is specific to the President of the Republic and does not apply to the prime minister or to other members of the government, is especially broad: the president cannot be made to appear in court for the duration of his term, whether for past or present offenses. Nor can he be investigated for any action whatsoever (again, with the exceptions noted above), in either a civil or criminal matter.

Only when the president completes his term can he be tried for offenses committed before, during, or after his time in office. However, the statute of limitations is suspended as long as he serves, and the clock begins ticking or is rewound, when he returns to private life.

The debate about the investigation and trial of an incumbent president became relevant in the case of Jacques Chirac (president 1995–2007), who was suspected of corrupt dealings committed, when he served as mayor of Paris, before his election as president. Chirac asserted his immunity and refused to be questioned.. The court backed him up and even expanded the scope of presidential immunity by assigning priority to the dignity of the presidency, the president’s proper performance of his duties, and the stability of the regime, over the temporary injury to the police and court proceedings. After Chirac completed his second term, he was tried for these offenses. In December 2011, he was convicted and given a suspended sentence.

Brazil

Brazil is a presidential democracy with provisions for the removal of a sitting president. As in other countries, this is a political process rather than a criminal proceeding, and requires a two-thirds vote by both houses of parliament. Recently, this mechanism was invoked against President Dilma Rousseff, who was suspected of administrative malfeasance. After the lower house of parliament impeached her, in December 2015, the Senate voted to suspend her for the duration of her trial. In August 2016, she was removed from office by a majority vote of the Senate.

South Korea

South Korea is a presidential democracy in which the president is chosen by direct popular election. The country’s constitution specifies an impeachment procedure to be invoked, should the president, prime minister, another government minister, judge, or other senior official violate the constitution or act unlawfully in the performance of their duties. The impeachment bill must be passed by a majority of the National Assembly, except in the case of the president, when a two-thirds majority is required (at least 200 of its 300 members). The impeachment bill stipulates that those charged will be suspended from their duties until a final decision has been reached about their removal from office. The next stage is a hearing by the Constitutional Court, whose approval is required to actually remove the president from office. The court may not deliberate for a period longer than 180 days, before publishing its decision.

President Park Geun-hye, charged with corrupt behavior, was impeached and suspended from office in December 2016. While the suspension was in effect presidential authority was wielded by the prime minister. The Constitutional Court affirmed her removal in March 2017, after which the prime minister continued to serve as acting president until new elections were held two months later, as provided for by the constitution.

In this case, as in Brazil, the president did not resign despite the charges against her, and was removed from office through a constitutional procedure that lasted for a number of months, during which she time was stripped of her powers.

We can conclude, then, that in a presidential system the main political mechanism for removing a president is impeachment. It is important to note that this process is entirely political and has nothing to do with criminal proceedings. It does not render them redundant, and the success or failure of the impeachment bill is irrelevant to a decision on criminal charges.

Summary

We have seen that in most countries, it is possible to initiate criminal proceedings against an incumbent head of the executive branch. To the best of our knowledge, however, in none of the countries surveyed is there a constitutional obligation for the president or prime minister facing charges to resign or suspend himself. In both the parliamentary and presidential systems, there are political mechanisms (a vote of no confidence or impeachment) that the legislative branch can put into effect in these circumstances.

Note that Israeli law, despite its ambiguity, is nevertheless relatively detailed when it comes to the circumstance of an investigation and indictment of a prime minister. In Israel, though, we do not seem to be able to rely on the ethics of elected officials, the political culture, personal integrity, and the “court of public opinion”. Until all of these are internalized, there may be a need for clear and precise legal mechanisms and rules, to navigate the country to a sustainable system of law and order.

The article was published in the Jerusalem Post.