More Supply than Demand: Israel’s Labor Market

Behind the record number of job openings, in an age of full employment and an economy with rapid growth, what steps can the government take to promote the inclusion of workers currently outside the job market and to help businesses?

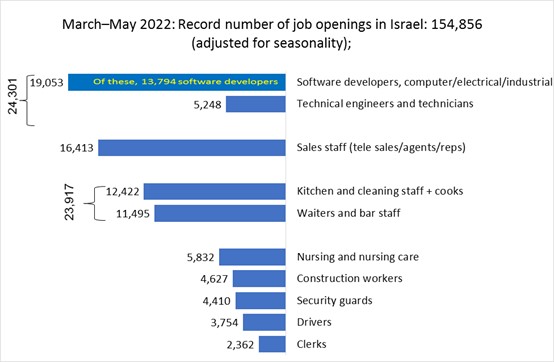

The fact that Israel’s economy has returned to a state of full employment is reflected in the increasingly severe shortage of workers. According to Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) data as of May 2022, this shortage of workers is being felt across the board, in all sectors, including professional workers for technological industries (especially hi-tech), which currently account for around 16% of the total available jobs, as well as workers in relatively low-paying sectors such as sales, the restaurant sector, cleaning, nursing, construction, security, and driving, which together account for more than a third of the total available jobs.

Against the backdrop of the crisis in the hi-tech industry over the last two months, which has provided a correction to the sharp rise in the value of hi-tech companies during the coronavirus pandemic, it is reasonable to assume that the lack of professional workers in that sector has eased somewhat since these figures were published. However, there is no doubt that there is still a shortage of workers in the industry’s core areas.

This shortage of both professional and other workers represents a barrier to economic growth, as businesses are forced to decline orders due to a shortage of staff. As a result, the economy is missing out on growth opportunities, while simultaneously, there is pressure from workers to increase wages and improve their conditions.

At first glance, these would seem to be “rich people’s problems”—an economy enjoying rapid growth and full employment is facing a worker shortage. But the tables can turn quickly, as we are now seeing in the hi-tech industry, and it is the government’s responsibility to address this shortage of workers.

So what can the government do?

The government should rapidly expand training for employees for in-demand sectors, in cooperation and coordination with employers, with the government’s contribution to the cost of training to be linked to the effectiveness of placement in each sector-that is, the extent to which training graduates are actually placed in jobs. Government intervention in professional and vocational training is a widely accepted practice around the world, based on the understanding that there is a market failure in this area, given that the returns to the economy as a whole from professional training are higher than the return on investment for individual employers. It is important that the government participate in and support effective training, with an emphasis on sectors that reward workers with high salaries and have high placement rates.

In addition, the government must continue to act to encourage the integration into the labor market of workers currently outside the workforce. These are mainly, though not exclusively, Arab women and Haredi men, two groups with a low rate of participation in the workforce.

Another challenge facing employers in Israel and around the globe is that of workers who were employed in low-paying jobs before the pandemic (particularly in sectors which were shut down during the lockdowns, such as salespersons, waiters, cooks, hotel staff, dockworkers, airport workers, and more) and who do not want to return to those positions. This situation poses a difficult challenge for employers throughout the world: One solution would be to raise salaries significantly in order to attract workers, but not all businesses can do so and remain profitable, particularly in traditional industries in which salaries account for a large share of overall costs. Another solution would be the adoption of technologies that replace workers who have left and are unwilling to return, though again, this is not an option for many businesses.

In this context as well, the government can assist businesses that are struggling to attract workers by helping them adopt advanced technologies that can replace some of their workforce, and that can improve efficiency and profitability. However, as noted above (and luckily for all of us), not every worker has a digital or technological replacement.

The article was published in the Times of Israel.